Stan Cliburn

Stan Cliburn became a catcher at the Boys Club. Baseball coach J.D. Rushing1 needed one for practice, so he chose the 7-year-old Cliburn and advised, “If you get good at this position, cherish this position, and work hard, you might be a major league baseball player one day.” Cliburn followed Rushing’s advice. In 1980 he played for the California Angels. In 1988 he retired as a player and began a prolific 30-year minor-league managerial career.

Stan Cliburn became a catcher at the Boys Club. Baseball coach J.D. Rushing1 needed one for practice, so he chose the 7-year-old Cliburn and advised, “If you get good at this position, cherish this position, and work hard, you might be a major league baseball player one day.” Cliburn followed Rushing’s advice. In 1980 he played for the California Angels. In 1988 he retired as a player and began a prolific 30-year minor-league managerial career.

Stanley Gene Cliburn was born on December 19, 1956, in Jackson, Mississippi. He was the second child of Gene and Geneva Cliburn. Twenty minutes later their third child Stewart Cliburn was born.2 He was Stan’s identical twin, with the same passion and talent for baseball. The twins joined their older sister Regina in their new single-family home a few miles west of downtown Jackson. Brother Roger was born 10 years later.

The twins were inseparable. “It’s like being a brother, but magnified,” said Stew. They went to the Boys Club together, dressed alike, and were elementary school classmates. Once they were assigned different teachers. “Our mother wouldn’t have anything to do with that,” said Stew; the twins were reunited.

The Cliburn family lived in Mississippi for several generations.3 Gene Cliburn was an auto parts salesman and Geneva, a former bank teller, was at home. “My Dad worked for every dime he had,” said Cliburn. “He appreciated the concept of hard work. He earned money the right way — being honest. My mother did the same.”

The twins’ Little League team won the championship with an 18-1 record, said Cliburn. “Stew would pitch a game and I would catch it, then I would pitch a game and he would catch it,” he said. Stan had the single loss, so Stew decided, “I must be a better pitcher than you.” Stew became the pitcher and Stan the catcher.

In 1970 the civil rights movement swept through the Jackson schools. After years of protests, demonstrations, and deadly violence in Jackson that made national headlines, desegregation of the schools created turmoil for families.

The new school district map moved ninth graders Stan and Stew from Hardy Junior High, less than a mile from home, to Enochs Junior High, a downtown school three miles away. It created a family and ethical dilemma. Their father had lived in mixed-race rural Mississippi, said Stan. “We had respect for all human life. We learned that through our parents. My Dad grew up all around African Americans in South Mississippi.” White students left the Jackson schools for tuition-only private schools. “A majority of our friends went to private school. We couldn’t afford it,” said Cliburn.

The contrast between the neighborhood and downtown schools and the social unrest prompted the Cliburns to move their children out of the Jackson schools. “My Dad knew that tension and he didn’t want that to interfere with anything we were trying to do,” said Stan. Using the address of the new family business, Gene Cliburn Machine Works, outside of Jackson, Stan and Stew enrolled at the county-run Forest Hill School.4

The business address worked for ninth grade – but the baseball coach said they needed to live in the school district to play sports as sophomores. The Cliburns bought a parcel of land and a trailer in the county school district. The family lived there, and the twins played football, basketball and baseball on integrated teams at Forest Hill.5

In his junior year, the basketball team was integrated, said Cliburn.6 He socialized cautiously. “My best friends in high school were two black running backs because we were teammates,” he said. “If they came to my neighborhood, which was predominantly white, they were scared or not allowed to get out of their car. I’d come down to the street. They’d roll the window down, shake hands, say hello and they’d drive off.”

In their senior year, 1973-74, Stan was football quarterback and punter. Stew was a wide receiver and defensive back. They earned Little Dixie All-Conference honors7 and received scholarship offers from NCAA Division II Delta State University. They were starting guards on the basketball team. “We knew each other’s moves,” said Stew. Baseball-reference.com lists both Stan and Stew as being 6’0”, 195 pounds.

Major league baseball scouts watched the Cliburns as they led Forest Hill High School to its first state Class AA championship with a 29-1 record.8 Stan, the conference MVP, hit .4509 and was home run leader. Stew won 20 games combined as a junior and senior and hit over .400.10

“When I started developing as a catcher, I took my quarterback football mentality and would take charge,” said Cliburn. “I took pride in my catching, blocking, and throwing. My main focus was to call pitches to get that pitcher where he needed to be.”

On June 7, 1974, Cliburn was on the senior class trip in Dallas playing golf. Between shots he opened the sports section of the local newspaper, and discovered that the California Angels had selected him in the fifth round. There to share the news was chaperone and long-time YMCA mentor J. D. Rushing. (Stew was selected in the 16th round of the same draft by the San Francisco Giants, but did not sign, choosing instead to play baseball at Delta State University.)

Cliburn’s father telephoned, “You’ve got to get home. The scout’s been over here to the house.” Angels scout Bob Reasonover offered a $12,000 signing bonus plus $10,000 in incentives,11 including $5,000 if Cliburn played in the major leagues for 90 days. “If it doesn’t pan out,” reasoned Cliburn, “I’ll take the money and come back and go to school.”

In the Summer of 1974 Cliburn reported to Idaho Falls of the Pioneer League (rookie ball). Just 17, he was the youngest on a team filled with college draftees and high school players from baseball hotbed California. “Those guys were about 30 years ahead of me,” he said. “I had to adjust quickly. I took pride in everything I did.” He could catch fastballs, but he learned to handle breaking pitches in the bullpen. Cliburn was among the team leaders with a .285 average, an OPS of .771, and 35 RBIs in 64 games.

In 1975 the Angels advanced Cliburn to Quad Cities (Davenport, Iowa) in the Midwest League (Single-A). But after two months, he said, “I was overmatched, and I knew it.” In 27 games he hit .200. His parents were in Davenport when he was sent back to Idaho Falls in late June. “I cried on my mom and dad’s shoulders,” said Cliburn. “Maybe I wasn’t that good.”

A collision at home plate sidelined him. “I milked it for 10 days. I didn’t want to play,” said Cliburn. He watched Idaho Falls’ other catcher, Floyd Rayford, play every inning. “This is weak,” he told himself, then asked, “Are you going to be a teammate or an individual?” For the last 40 or 50 games, he said, “I enjoyed playing again.” He hit .251 with a .393 OBP in 57 games.

Cliburn returned to Quad Cities in 1976 and shared catching duties with Marty Martinson, a second round 1974 draftee, and future major-league manager Joe Maddon.12 “Joe was like the Wizard of Oz on our team,” said Cliburn. “If there was any problem, we didn’t go to [manager] Moose Stubing to get answers. We went to Joe Maddon.” On the field, said Cliburn, “He pushed me. I pushed him. We competed.” In 76 games Cliburn hit a team-best .305 and was among its offensive leaders.13

In 1977, the 20-year old was invited to the Angels’ major-league spring training in Palm Springs, California,14 where he caught Nolan Ryan and Frank Tanana in the bullpen. “This is my dream,” said Cliburn. “It was intimidating, but I knew I had to feel tough, look tough, be stern – and here’s the old quarterback coming out in me – be positive and take control.” It worked. Cliburn played over 100 games for Single-A Salinas (California League), hitting .311 with a career high .855 OPS. He was selected to the All-Star team.15

In 1978 Cliburn was added to the Angels’ 40-man roster.16 He was assigned to Triple-A Salt Lake City (Pacific Coast League) and tabbed as the Gulls’ starting catcher. He was the third-youngest player on the team. “I was overmatched, and they knew it, but they kept me in there,” said Cliburn. In 47 games he hit .210, 81 points below the league average. In late June he hurt his ankle and finished the season in the Texas League with the Double-A El Paso Diablos.

In his second week with the Diablos, he hit two home runs in one game at Dudley Field, where El Paso fans would circulate a batting helmet to collect dollar bills after a home run. “I made $330 cash, which was more than I made in a two-week paycheck,” he said. He played 30 games and hit .194. El Paso won the Texas League championship by beating the Jackson Mets, winning the first two games in Cliburn’s hometown before family and friends.

In February 1979 Cliburn married Tanya Smith.17 Their son Patrick was born in November 1984.

Cliburn returned to Triple-A Salt Lake City in 1979, sharing catching duties with Dan Whitmer as the Gulls won the PCL championship. In 62 games Cliburn hit .238 with 4 home runs and 26 RBIs. His season’s highlight occurred on August 21 in Portland, Oregon. When Cliburn batted in the eighth inning, the opposing pitcher was his brother Stew, who had turned professional after being drafted in 1977 by the Pirates. It was the first time he had ever faced his brother. “He knows I’m a fastball hitter,” said Stan, and Stew threw one. “The first pitch I see, I pop it up to the first baseman.”18

In 1980 Cliburn, 23, was Salt Lake City’s starting catcher. Seven games into the Gulls’ season, the big club’s All-Star catcher, Brian Downing, broke his ankle. Cliburn flew to Minneapolis to join the Angels, who were off to a slow start after winning the AL West in 1979. He became a reserve behind California’s new primary catcher, Tom Donohue, a light-hitting first-round 1972 draft pick.19 “They used me a lot in the late innings,” said Cliburn, when manager Jim Fregosi pinch-hit for Donohue and Whitmer, a midseason call-up. When the Angels played in Texas on May 22, Fregosi started Cliburn. In the stands were over 160 family members and friends who drove 400 miles from Jackson to Arlington Stadium.

Friends included three of Cliburn’s Jackson pals who snuck on to the field before the game. “They were behind the batting cage watching me and Rod Carew,” said Cliburn. “These guys were so bold. Then the game is starting, and Fregosi looks down the dugout bench and asks, ‘Who are those three guys down there?’ Meanwhile, Cliburn’s father Gene savored the game undisturbed. “He was at the very top of the stadium [in the second deck] by himself,” said Stan. After the game Cliburn’s buddies got into the Angels’ clubhouse and drank beer intended for players.

In that May 22 start, Cliburn got his first major-league hit, off Jon Matlack, and scored on a Carew single. He got a second hit and also lined out into a double play in a 12-6 loss to the Rangers. After the game Fregosi told Cliburn, “I liked what I saw tonight. You’re going to be my catcher here for a while.”

But he didn’t start again for a month. “It crushed me,” said Cliburn. He speculated that his out of bounds visitors in Texas may have contributed. He surmised Fregosi’s take: “Here’s a rookie being seen but he’s also being heard.”

Beginning on June 25, however, Cliburn started nine of the Angels next 14 games, and over a one-month period, 13 of his 18 appearances were starts. During that period, he hit .175 and the Angels went 11-18, stuck in last place. On July 25 he hit his first home run, off the Indians’ Ross Grimsley. A week later after a game in Toronto, Cliburn hurriedly entered a taxicab, only to find it was already occupied. The passenger looked at him and said, “Congratulations on your first major league home run.” It was Bobby Doerr, the Blue Jays’ hitting coach.

Cliburn’s biggest 1980 memory occurred at the All-Star break. He was invited by American League President Lee McPhail to be an AL bullpen catcher for the 1980 All-Star game at Dodger Stadium in Los Angeles. He spent three days with his boyhood idol – future Hall of Famer and perennial All-Star catcher Johnny Bench – and honorary captain Al Kaline, whose locker was adjacent to his. After rubbing elbows with the top players in the game, Cliburn rejoined the Angels who, at 29-48, had the worst record in baseball. “Going back to Anaheim was almost like getting sent back to Triple-A,” said Cliburn.

After the All-Star break, Cliburn needed about 10 more days with the Angels to trigger his incentive bonus of $5,000 for 90 days of big-league service time.20 On the 89th day, Cliburn announced to the clubhouse, “My 90th day is tomorrow. Drinks on me tomorrow night.” Later that day, Fregosi called Cliburn into his office and said that he was being sent back to Double-A El Paso. Cliburn implored the manager to send him to Triple-A instead – and to wait a day until he earned his bonus. At that moment Joe Rudi, Don Baylor, Donohue, and Downing burst from the manager’s bathroom laughing at their practical joke. Cliburn would stay with the Angels through the end of the 1980 season.

For the season, Cliburn hit .179 with two home runs and six RBIs. He appeared in 54 games and started 16. After his July 25th home run, Cliburn started just once, on August 17, when he hit his second home run of the season, a solo shot off Jerry Koosman. “I never got the chance to play on a consistent basis,” said Cliburn. “I never understood why. It wasn’t like the other guys were knocking the place dead.”21

In 1981 Cliburn was dropped from the 40-man roster. When spring training ended, he thought he had secured the Triple-A catching job, so he prepared to drive with his wife Tanya to Salt Lake City. “I see [general manager] Mike Port running out of the clubhouse trying to wave me down.” Port told Cliburn he had been released because the Angels had signed free agent veteran catcher Bob Davis. “It was the toughest day of my life,” said Cliburn. The Cliburns drove to Jackson instead and waited for an invitation back to baseball.

In mid-June, opportunity knocked, with a bonus. The Pirates’ Double-A affiliate, the Buffalo Bisons, needed a catcher – and one of their pitchers was Stew Cliburn, who was still in the Pirates organization. It had been seven years since the twins were teammates. “It was like going back to high school,” said Stan. In the Cliburn battery’s second game, Stew threw a two-hit complete game, winning 6-2. In 62 games, Stan hit .253 with 5 homers and 24 RBIs.

After the catcher played winter baseball in Barranquilla, Colombia, the Pirates promoted him to Triple-A Portland in 1982. He backed up Junior Ortiz but missed two months with a broken wrist. He hit .177 in 27 games.

The Pirates sent Cliburn down to Double-A Lynn (Massachusetts) of the Eastern League in 1983, but he said, “It was one of the most fun summers I’ve had.” He was the Sailors’ starting catcher and played 121 games with 15 homers and 68 RBIs, all personal highs.

That winter he was the starting catcher for Magallanes of the Venezuelan Winter League, his second season in highly competitive Caribbean baseball. He led the team in home runs and was second in RBIs.22 The 26-year-old reminded himself, “I’m not in the big leagues of the United States, but I’m in the big leagues of Venezuela.”23

The Pirates promoted Cliburn to Triple-A Hawaii of the PCL in 1984. He believed he had major-league credentials. “I was handling their young prospects,” said Cliburn. “I was going to winter ball and doing well. I was playing the best I’d ever played in my life.” He played 89 games in Triple-A and registered a .728 OPS, but did not get a call-up to Pittsburgh, who had All-Star Tony Peña behind the plate, backed up by veteran Milt May.

However, Cliburn became part of baseball history in 1984 without stepping on the field. On September 17, brother Stew made his major-league debut with the Angels, making the Cliburns the seventh set of twins to play at the top level and the third to play for the same team.24

However, Cliburn became part of baseball history in 1984 without stepping on the field. On September 17, brother Stew made his major-league debut with the Angels, making the Cliburns the seventh set of twins to play at the top level and the third to play for the same team.24

Cliburn returned to Hawaii in 1985 and played in just 54 games, a career low for injury-free seasons. In Pittsburgh, the rising Ortiz backed up Peña. “That’s when I knew I wasn’t going to be the guy in Pittsburgh,” said Cliburn.

In 1986 the Angels signed Cliburn as a free agent, where he rejoined Stew. The twins played for the Triple-A Edmonton Trappers in the PCL. In 80 games Stan hit .267. His .812 OPS was third highest among Edmonton starters.

Cliburn hit well during 1987 spring training, and there was a potential opening with the Angels. If free agent Bob Boone re-signed with California, he would not be able to play until May 1.25 But on April 2, Cliburn was traded to the Atlanta Braves for Double-A third baseman Joe Redfield. He caught 18 games for Triple-A Richmond, hitting just .148 before he was released. Cliburn was at home for just two days when the Angels asked him to catch at Edmonton again. He played with the Trappers until late June when the Angels asked him to serve as a player/pitching coach at Double-A Midland (Texas).

Cliburn, then 30, joined the Texas League team for several weeks – but it was all coaching and no playing. “I’m tearing up the Cactus League [in spring training] and three months later you’re going to make a coach out of me?” said Cliburn, “I’m not ready for that.” So, when a catcher in Triple-A Edmonton was promoted to MLB toward the end of the season, the Angels activated him again. In 23 games total with the Trappers, he hit .227 with eight extra-base hits and 13 RBIs.

In 1988 Cliburn was tempted to continue playing until the Pirates offered him a coaching job at $35,000, double his player’s salary. He coached for the Pirates’ new Triple-A franchise in Buffalo until mid-June, then managed the short-season Watertown (New York) Pirates. “The main thing I learned as a manager,” said Cliburn, “it’s not about you anymore. It’s about 25 players with different styles of play and different egos and you have to adjust to each of those 25 players.”

Cliburn learned to balance winning and player development. At first, he believed “if you play fundamental baseball, winning should take care of itself if you have any kind of talent.” So, the season was a disappointment when Watertown finished under .500. In 1989 Cliburn managed the Augusta Pirates to the South Atlantic League championship. The championship was Cliburn’s first as a manager and fourth professionally.26

In 1990 in the Single-A Carolina League, Cliburn’s Salem Buccaneers won their first four games. He was pleased but farm director Chuck LaMar observed that Cliburn had used the same starting lineup every game. “How do you think the other three players feel?” said LaMar. “I think you need to learn how to lose.” Salem finished well below .500 in 1990 and 1991. Indeed, said Cliburn, “I learned how to lose. I didn’t like it, but it made me a better manager.” His contract was not renewed during a subsequent front office transition. Cliburn then joined the Rangers organization.

During three years in the Texas chain, he was hitting and first base coach with the South Atlantic League’s Gastonia Rangers, and then for two years manager of the Double-A Tulsa Drillers. He was not rehired after the Rangers changed general managers in late 1994.

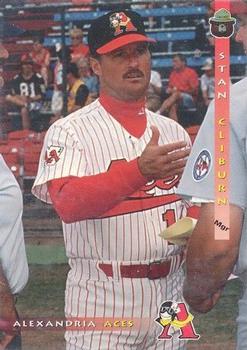

In 1995 Cliburn was hired to manage the Alexandria (Louisiana) Aces of the independent Texas-Louisiana League.27 Out of affiliated baseball, Cliburn no longer had to spend hours after every game preparing player reports for the front office. Instead, he recruited players and supported those at career crossroads. “It was exhausting,” he said. “There were no other coaches.”

Nonetheless, Cliburn thrived on the pressure. “It was all about winning,” he said. For the players “they either put up good numbers or their career is over.” In five years, the Aces qualified for the playoffs four times and won the championship twice.

After 1999 Cliburn was recruited by the rebuilding Minnesota Twins, a club that had averaged 66 wins over the prior seven years. He was hired by former Edmonton teammate Steve Liddle, who’d become the Twins’ field coordinator. “I knew his personality,” said Liddle. “He was one of the baseball lifers who was in baseball for the love of the game, not themselves. That was someone that we needed to help us attain the Minnesota Twins’ goals in player development.”

Cliburn, by then 43, managed Single-A Quad Cities in 2000. After a sub-.500 season Stan was named manager of Double-A New Britain in 2001, joining Stew, who was the Rock Cats’ pitching coach. The Cliburn duo “was a great dynamic,” said Liddle. “They fed off each other. They were each other’s quality control guys.” Still, Stan felt the stress. “There was more pressure on me as manager and Stew as pitching coach since the day I signed in 1974.”

The 2001 Rock Cats were the Eastern League’s co-champions, with a roster that included 14 future major-leaguers.28 Stan said he and Stew shared a vision of “game preparation, player development, how to carry yourself in public, how to be a professional signing autographs and be a professional with the uniform off.” New Britain celebrated the twins by having a two-sided Cliburn bobblehead promotion.

Over the next four years, the Cliburns developed everyday players who helped bring the Twins six AL Central Division titles from 2002 to 2010.29 “The atmosphere was conducive to learning and winning and playing the game the right way,” said Liddle. “It allowed us to develop our top prospects to become championship players,” including Joe Mauer, Francisco Liriano, Justin Morneau, Michael Cuddyer, Kyle Lohse, and Juan Rincon. In 2005 Cliburn managed his 2000th game and won his 1000th.

In 2006 Cliburn was named manager of the Twins’ Triple-A farm club, the Rochester Red Wings, and Stew joined him again as the team’s pitching coach. The Red Wings finished over .500 for three consecutive years, including 2006, when they lost the International League championship to Toledo, three games to two. The Twins front office, said Liddle, also relied on the Cliburns’ postgame opposition scouting reports. To prepare for trades and the Rule 5 minor-league draft, said Liddle, after every game, “they had to write a thorough report on every position player and pitcher that they saw.”

With the Twins, Cliburn managed players from 10 countries30 and every region of the United States – an array of many ethnicities and backgrounds. “I was prepared for that because of what I went through as a kid,” said Cliburn. “It was never a color thing for me. It was always people. As a young man I learned how to deal with racial tension and how to deal with different cultures.”

In 2009 Minnesota moved Stew back to New Britain. “I don’t know why,” said Stan. “Maybe they wanted to see how I worked with a different pitching coach.”31 Also, their widowed mother was very ill. “I felt lost, and Stew is not here with me,” said Stan. “I had no leadership qualities. The players saw that. Management saw that.”

After his mother’s funeral in August, Cliburn was advised, “Your players aren’t responding to you.” Rochester had its first losing season since 2003. Cliburn’s contract was not renewed. “Baseball,” said brother Stew, “it’s a great game but sometimes it steps on your heart.”

In 2010 Cliburn returned to independent baseball as the hitting coach for the Tucson Toros of the Golden Baseball League. That year he also made his film debut in the public television series Minor League, about the 2009 Rochester Red Wings season. Producer John Campbell described the storytelling Cliburn with his Southern drawl as “the biggest character out of this whole show.”32

Cliburn continued in independent baseball in 2011, managing the Sioux City (Iowa) Explorers of the American Association. The disparity between Triple-A and unaffiliated baseball gnawed at him. “I was older and didn’t have the fire. Wins and losses didn’t mean as much,” he said. In three years, the Explorers’ victory totals slid from 51 to 38.

Off the field, the loss of Cliburn’s parents lingered. “I was struggling with myself,” he recalled. He abused alcohol until he realized it “was interfering with what I wanted to do in life – be a baseball manager,” he said. He successfully completed an outpatient program. “It was the best thing I’ve ever done,” he said.

In 2014, at 57, Cliburn was rejuvenated as the hitting and bench coach for the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Barnstormers of the independent Atlantic League, managed by Butch Hobson.33 “I couldn’t wait to get to the park,” he said. The level of competition also inspired him. “It’s the highest level of independent baseball, mostly former major-leaguers, Triple-A and Double-A players,” he said.

As manager for the Atlantic League’s Southern Maryland Blue Crabs in 2015, Cliburn managed his 3000th game. The following year he helped the Atlantic League launch a new franchise, and he returned to New Britain after a ten-year absence. He was named Manager of the Year, but attendance was down, and the now-independent location had “lost its feel,” said Cliburn. He left to be Hobson’s bench coach in 2018, this time with the Chicago Dogs of the American Association. Also that year Cliburn appeared in the award-winning documentary Late Life, about the comeback of pitcher Chien-Ming Wang.34

Cliburn returned to South Maryland as manager in 2019, the year the Atlantic League became an official partner with MLB and test site for new rules including larger bases, infield shift limits, and a pitch clock. Two years later the league tested robo-umps to call balls and strikes and a longer pitching distance.

Blue Crab outfielder Dario Pizzano said Cliburn gave players advice about the rules experiments: “Everybody has to do the same thing. I don’t want to hear anyone complaining. Make the adjustments.” Cliburn also told players the new rules would boost their careers. “We’re getting publicity on MLB Tonight and ESPN Top Plays,” he said, “We now have major league personnel coming into our clubhouse.”

Pizzano, then 30, received strong support from Cliburn as he pursued a major-league baseball career in 2021. “He had his players’ back – always,” said the 2012 Mariners draft pick. “I struggled for the first six weeks at the plate, and he kept me in the third spot [in the batting order]. Stan said, ‘Just keep doing your thing. We know it’s going to come around.’”35

In midseason Pizzano hurt his back, then left the Blue Crabs briefly to play with Team Italy to help secure a spot on its World Baseball Classic roster. “Stan could have released me because I was taking up too much money [within the team’s payroll] and bring in a couple of other players,” said Pizzano. “He told the general manager to keep me on the team.” When Pizzano returned, the roster had tightened, so Cliburn got him traded to a team where the first baseman/outfielder could play regularly.

Through 2022, in 3,790 minor league games, Cliburn had 1,898 wins as a manager, 21st on the all-time minor-league/indie ball list.36 He has a contract for 2023 with Southern Maryland. A complete season at the helm would put him less than a full season away from 2,000 wins and 4,000 games as a minor-league manager.

After 30 seasons as a manager, Cliburn is most gratified about managing the range of talent on a minor-league roster. “Ninety-something percent of players… aren’t going to make it, so you have to make them feel like every day that they have a chance,” said Cliburn. “You have to make the 40th pick feel as good as the number one pick. You have to have them all equal. When you do that, you become more team-oriented and have a team concept.” Then with skill development, said Cliburn, “Players look forward to coming to the ballpark every day. When you do that, winning is icing on the cake.”

Last revised: January 10, 2023

Author’s Note

The author met Stan Cliburn in 2002 at a winter baseball instructional camp in Fort Myers, Florida. They both returned every year to share their passion for baseball. In 2016, when the author was 60 years old, he asked Cliburn if he thought a minor-league team might allow him to play in a game to fulfill his lifelong dream of playing professional baseball. With Cliburn’s support the author began an 18-month search that concluded with a two-game stint as a pitcher and outfielder at the age of 61 with the White Sands Pupfish of the Pecos League in 2017.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Larry DeFillipo.

Sources

All observations by and quotations attributed to Stan Cliburn were obtained in telephone interviews on October 13, 19, and 20, and November 25, 2022, and in subsequent emails and text messages.

Stew Cliburn, telephone interviews, October 27 and November 13, 2022

Steve Liddle, telephone interview, October 24, 2022

Dario Pizzano, telephone interview, November 19, 2022

Baseball-reference.com

Baseball Hall of Fame Library, players files for Stan and Stew Cliburn

Notes

1 J.D. Rushing was then 18, loved sports, and lived in McComb, Mississippi. He later became the Executive Director of the Northside Drive YMCA in Jackson and retired in 2004 after a 38-year career for the YMCA community. https://www.iviefuneralhome.com/obituaries/JD-Rushing-Jr?obId=7599237, accessed December 5, 2022.

3 The Cliburns settled in Mississippi after their ancestors migrated down the east coast of the United States from Georgia, North Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland. Family roots included Ireland and Great Britain, according to genealogical information researched in Ancestry.com. The Cliburn family name transitioned from Claiborne in the late 1700s. https://www.ancestry.com/search/?name=Gene_Cliburn&birth=_jackson-mississippi-usa_1474&count=50&location=2&name_x=1_1&priority=usa&types=t , accessed December 5, 2022.

4 Forest Hill High School was officially established in 1978, the year after the area was annexed by the City of Jackson. The Junior High School was dissolved in the 1978-79 school year. http://www.foresthill1978.org/history.html, accessed December 5, 2022.

5 The 1974 Forest Hill High School yearbook includes pictures of the football, baseball and basketball teams, all of which include white and black students. https://www.ancestry.com/search/?name=Stan_Cliburn&event=_jackson-hinds-mississippi-usa_34923&birth=1956&count=50&gender=m&location=2&name_x=1_1&priority=usa , accessed December 5, 2022.

6 One basketball teammate was Larry Myricks, a four-time Olympian long-jumper, who won a bronze medal in the 1988 Olympics.

7 “DSC Announces Signings” Delta Democrat-Times (Greenville, Mississippi), December 2, 1973: C2.

8 The 1974 championship is the only state baseball title ever won by Forest Hill High School. https://www.misshsaa.com/2016/05/20/baseball-champions/ , accessed December 5, 2022.

9 UPI, “Cliburn to Angels,” Delta Democrat-Times, June 12, 1974: 11.

10 “DSC Announced Signings.”

11 “Cliburn to Angels.”

12 Cliburn played in 76 of the team’s 131 games. Maddon, who had just graduated from Lafayette College, appeared in 50, and catcher Marty Martinson, who was drafted three rounds before Cliburn, played in 43.

13 Maddon hit .295 in 50 games.

14 Dick Miller, “Will Angels Find Another Hartzell?” The Sporting News, February 26, 1977: 38.

15 With Salinas, Cliburn went body surfing for the first time with teammate Brandt Humphry, a California native. He hurt his arm but told manager Moose Stubing it happened on an awkward swing. Decades later, Cliburn confessed the fib to Stubing, who said, “I knew something was up, Cliburn.”

16 Tracy Ringolsby, “Angels Efforts to Land Mauch Hinge on Today’s Meeting with Twins Boss,” Press Telegram, (Long Beach, California), November 19, 1977: 32.

17 They were divorced in 1992.

18 Cliburn said he was 3-for-10 with no home runs or strikeouts against Stew over their minor-league careers. His biggest at-bat was in the final game of the 1984 Pacific Coast League Championship series. Stan, playing for Hawaii, came to the plate with two out, but Stew got him up to pop up to the first baseman and the pitcher’s Edmonton team won the title. That night Stew was called up to the majors by the Angels.

19 Donohue hit .188 in 84 games in 1980. He had seven extra base hits in 218 at-bats. The Angels also purchased Dave Skaggs from the Orioles on May 13. He had seven hits in three games from May 14 to 17 but hurt his ankle and was sidelined until September. Dan Whitmer was called up in mid-July and started 33 games, appearing in 48 overall.

20 By 1980 the major league minimum salary had doubled from the 1974 minimum of $15,000, but the bonus was still equal to about a full months’ pay for Cliburn.

21 Donohue hit .188, Whitmer hit .241, and Skaggs .197 with a combined three home runs. Defensively, all three catchers were below the 35% A.L. average for caught stealing. Cliburn’s was 23%, Donohue’s was 26%, and Whitmer’s was 29%. Downing’s was 5%.

22 Pelotabinaria – Venezuelan winter league website (https://www.pelotabinaria.com.ve/beisbol/tem_equ.php?EQ=MAG&TE=1983-84 , accessed December 5, 2022).

23 Cliburn returned to Venezuela in the winters of 1984-85 and 1985-86 and played for Caracas. He played in 46 games over the two seasons.

24 As of 2022, there have been 10 sets of twins, according to Baseball Almanac (https://www.baseball-almanac.com/family/fam7.shtml , accessed December 5, 2022).

25 The terms of the players’ collective bargaining agreement with MLB dictated that a free agent re-signing with his team after January 8 could not play before May 1.

26 His championships as a player were: 1974 Idaho Falls, Pioneer League; 1978 El Paso, Texas League; and 1979 Salt Lake City, Pacific Coast League.

27 The Texas-Louisiana League operated from 1994 through 2005 with between six and 10 teams. It was known as the Central Baseball League for its last four years. In order to maintain parity, team rosters were managed by the league.

28 The Eastern League playoffs were canceled after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. New Britain and Reading were declared co-champions. The most prominent major leaguers who played regularly for the 2001 Rock Cats were: Michael Cuddyer, Lew Ford, Grant Balfour, Dustan Mohr, and Juan Rincon.

29 In 2008 Cliburn managed a co-op team in the Arizona Fall League and guided Phoenix to the championship.

30 The countries were the Dominican Republic, Canada, Australia, Venezuela, Honduras, Vietnam, New Zealand, El Salvador, Mexico, and Japan.

31 Cliburn said he worked well with new pitching coach Bobby Cuellar.

32 Thomas Adams, “Major Production,” Rochester Business Journal, April 23, 2010.

33 The Barnstormers won the Atlantic League championship, Cliburn’s ninth as a professional.

34 Cliburn was interviewed when Wang pitched for South Maryland in 2015. This was Cliburn’s third movie and documentary role. In 2017, Cliburn had a brief speaking role and was the third base coach in High and Outside, about a failing minor-league player. It was shot at Lewis and Clark Park in Sioux City in 2013, Cliburn’s last year with the Explorers.

35 Pizzano hit .324 with a .909 OPS in 46 games with the Blue Crabs.

36 https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Minor_League_Wins_by_a_Manager , accessed December 5, 2022.

Full Name

Stanley Gene Cliburn

Born

December 19, 1956 at Jackson, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.