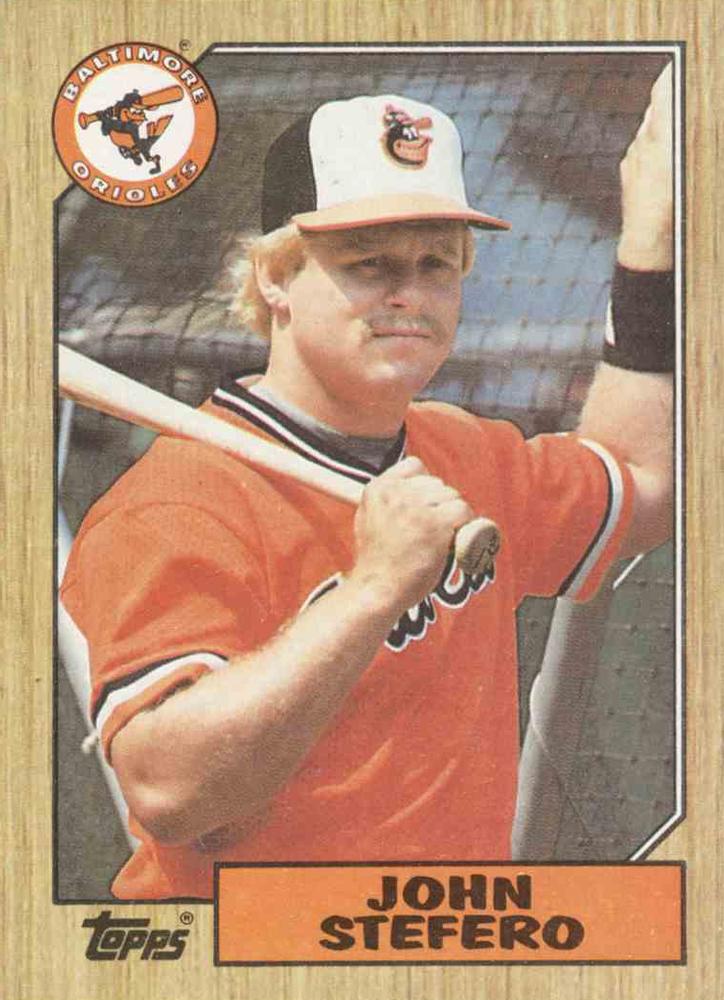

John Stefero

Before John Stefero was 30 years old, his baseball statistics included 18 broken fingers1, a fractured hand, and a cracked kneecap. “A catcher’s life,” he sighed. Over three major league seasons, the left-handed hitter also earned a World Series ring in 1983, standing ovations and curtain calls from his hometown fans, and enough memories and experiences for him to recall his time in the game as “very blessed”.

Before John Stefero was 30 years old, his baseball statistics included 18 broken fingers1, a fractured hand, and a cracked kneecap. “A catcher’s life,” he sighed. Over three major league seasons, the left-handed hitter also earned a World Series ring in 1983, standing ovations and curtain calls from his hometown fans, and enough memories and experiences for him to recall his time in the game as “very blessed”.

John Robert Stefero, Jr. was born on September 22, 1959, in Sumter, South Carolina. His father, John, Sr., grew up in Baltimore — where the younger Stefero would get his start in the majors. John Sr. attended Southern High School and played baseball a few years behind Al Kaline, the Hall of Famer who went straight from the school to the Detroit Tigers. One of the elder Stefero’s teammates was fellow outfielder Barry Shetrone, who signed with the Orioles after graduation. Stefero turned down his own chance to go pro, opting to join the Air Force instead.

When the Air Force sent him to South Carolina, he met and married Mary Elizabeth Brazil, a divorcee with a son, Timmy, from her previous marriage. Together they had John, Jr., daughter Carolyn, and son Donnie before divorcing while the children were still young. Young John went to live with his father in Baltimore. Shortly after he turned 12, the Orioles played in their third consecutive World Series. “Boog Powell and Dave McNally were my idols,” he said.2 “I always wanted to be a pro baseball player.”3

According to Baltimore Sun reporter Pat O’Malley, who coached Stefero as an amateur, “At 13, he became the star of the National Stove champion North Glen team.” In 1975, his age 14-16 Brooklyn Optimist club won the Baltimore City Cardinal Gibbons Championship. A state Babe Ruth League title in 1976 with Pikesville followed. At Mount Saint Joseph High School, he played four years of baseball — plus one season of football — and captained the 1977 Maryland Scholastic Association winners while earning all-MSA recognition as the league’s top second baseman. That summer, for the second straight year, he suited up for the state’s Babe Ruth League champs, representing Mike’s Auto Mart.4

After turning 18 that fall, Stefero spent his off-season working as a busboy at Bojangles Too, a popular music and dancing spot owned and managed by his father. He later worked there as a doorman. Stefero described his father as an entrepreneur who was also involved with an Anne Arundel County bingo hall. “He taught me to earn what you can get,” he said.5

During his days on multiple championship amateur teams, Stefero insists, “I wasn’t necessarily the best player, but I did my part as a teammate. We had lots of good players.” His teammates included Mike Bielecki and Larry Sheets.6 Jim Gilbert, a Baltimore scout, was one of his coaches, and helped introduce the 5-foot-8, 185-pound Stefero to the basics of catching. The Orioles had already been impressed by Stefero’s strong right arm at tryout camps, and Gilbert observed, “He’s an average runner, but has good power from the left side.”7

In 1978 Stefero headed south to play college ball. He planned to attend East Tennessee State, but couldn’t enroll because his high school transcripts never arrived. The baseball coach there arranged for him to play at Motlow State Community College instead, and Stefero bashed nine homers in the fall and another dozen that spring to break the school record.8 Playing catcher and third base, he batted .354 with a school record 48 RBIs,9 earning all-conference and all-Tennessee recognition. “I know I matured away from home and really improved,” he said. “I got stronger, and I started thinking about getting a chance to play pro ball.”10

Back in Maryland in 1979, he played for Johnny’s, the renowned semipro club managed by scout Walter Youse (then with the Milwaukee Brewers but who’d served many years in the Orioles organization). Stefero was a regular attendee at Orioles tryout camps, including one in Cecil County, Maryland in late June. The following night, the 19-year-old was in the lineup for a team of the area’s best amateurs to battle a visiting all-star team from Korea at Memorial Stadium. With Gilbert, Orioles scouting supervisor Dick Bowie, and scouting director Tom Giordano watching, the locals lost, 3-1, but Stefero homered over the 385-foot mark in right center. “That ball he hit against the Koreans really convinced me of his power potential because he hit that off a pretty good pitcher who was getting everybody else out,” remarked Giordano.11 Stefero also doubled. When the game was over, “Dick Bowie called me to the side afterwards and signed me then and there within 30 minutes. He told me to be in Bluefield [WV] tomorrow.”

With Baltimore’s rookie-level Appalachian League affiliate, he was called into the manager’s office within two weeks. “He said he couldn’t understand why I wasn’t drafted because he says I have ability,” Stefero recalled.12 Earning the standard $600 per month, the 19-year-old stayed with an elderly woman who fed him well. He hit .275 with a club-high eight homers and 42 RBIs in 59 games. He received a leather jacket to commemorate being named the team MVP.13

Though he played mostly third base, Baltimore already had a top prospect at that position whom they’d drafted the previous year. Stefero had played against him in Maryland once or twice, a former centerfielder/pitcher from Aberdeen named Cal Ripken, Jr. Stefero went to the Instructional League to work on becoming a full-time catcher under the tutelage of coach Lance Nichols, a backstop in the Dodgers’ chain in the 1960s.

Stefero moved up to the Single-A Miami Orioles in 1980. The team finished with the worst record in the Florida State League and — after May rioting that caused 18 deaths, hundreds of injuries. and millions of dollars’ worth of damage — some home games were played with National Guard troops in the stands, armed with M-16s. “That can shake you up,” he said.14 Baseballs notoriously did not carry well at Miami Stadium, and he batted only .215 with five homers in 101 games, though he did continue to progress at his new position. “A catcher should be the most aggressive player on the field, and John does that,” observed Nichols, Miami’s manager that season. “He’s improving all the time.”15

Though he wasn’t on the active roster, Stefero spent part of September with the Orioles as they won 100 games but just missed the playoffs. Then it was off to Cartagena, Colombia, for a difficult season of winter ball. He was traded and played more third base than he expected. He was chronically sick from eating unfamiliar food; his weight dropped from 189 pounds to 172 by season’s end and his batting average slid to .240. “If you don’t do well, they throw bottles and oranges at you,” Stefero told a Baltimore reporter. “If they don’t like you, you’re in trouble.”16

Baltimore sent him to their other Single-A affiliate in 1981, the Hagerstown (MD) Suns. On April 14, he was thrown through the window of the team bus when it overturned.17 Despite that, he enjoyed a breakout year, batting .287 with 25 homers and a club-high 82 RBIs. He also drew 78 walks for an outstanding .418 OBP. In the Carolina League All-Star Game, he smoked two more long balls and won MVP honors.18 Grady Little, his manager, said Stefero had “the most feared arm” in the league and Gilbert, the Orioles scout, called him “the talk of the town.”19 Despite a hairline fracture of his right thumb caused by a foul ball in August, Stefero played through the pain and helped Hagerstown win the championship.

The Orioles put him on their 40-man winter roster and promoted him to the Charlotte O’s of the Double-A Southern League. Though what he described as “a rather prolonged slump”20 dragged his batting average down to .230, the catcher notched 17 homers and 60 RBIs as the team’s most productive lefty slugger. Three of his first six round-trippers were grand slams,21 and he bopped a pair of three-run homers on July 7.22

When Baltimore sent him back to Charlotte to start 1983, Stefero looked like a player with nothing left to prove in Double-A, hitting .307 with 16 home runs in his first 205 at-bats. “One of the main things I learned in my years in pro ball was patience and learning to wait for my pitch and not going after the pitcher’s pitches,” he explained.23 He smashed seven homers in one 11-game stretch24 and was named a Southern League All-Star.25

On June 22, Stefero was playing cards in his hotel room in Columbus, Georgia, when he was called up to Baltimore. “The good news was I was going to play for the Orioles,” he said. “The bad news was it’s because Joe Nolan is hurt.26

“Walking onto the field at Memorial Stadium with my name on the back of an Orioles jersey was a feeling I can’t explain to this day,” he said. Since Stefero didn’t own the black and orange spikes Baltimore’s uniforms required, teammate Al Bumbry lent him a pair. Bumbry, a 5-foot-8 center fielder, and the similar-sized Stefero — “Stump” to his teammates — liked to joke about who was taller.

Stefero debuted on June 24, batting seventh and catching Dennis Martinez. The Orioles lost, 9-0, but he pulled an eighth-inning single off Detroit’s Dan Petry for his first major league hit, drawing a standing ovation from an announced Friday night crowd of 25,796 that included his father.

Against New York relief ace Goose Gossage on June 30, the rookie fouled off a few ninth-inning pitches before slicing a game-tying, two-run double into the left field corner at Yankee Stadium. “I’ll remember that one for the rest of my life,” Stefero said.27

When Nolan returned two weeks later, Stefero went to Triple-A Rochester. He homered in his first two games for the Red Wings.28 However, bothered by bone spurs in his left hand and torn muscles in his right knee, he fizzled to a .196 finish in 96 International League at-bats. “I couldn’t hit, throw or catch, and I was getting booed,” he said.29

Nevertheless, the Orioles brought him up for the September pennant chase. With his family and friends in the stands on Sunday, September 18, Stefero entered the game as a pinch runner in the third inning after Baltimore catcher Rick Dempsey was hit by a pitch. The Orioles were already losing, 7-0. He walked in his first plate appearance, then scored after reaching on an error his next time up. He scored again in the eighth inning after singling as part of a six-run rally that allowed Baltimore to come back and seize a short-lived lead.

The game was deadlocked, 9-9, when he batted in the bottom of the ninth with two on and one out against Brewers’ closer Pete Ladd. “All I wanted to do was make contact,” he said afterward.30 He lined a single to right to drive Glenn Gulliver home from second base with the winning run. “I was hoping Glenn could score. He’s as slow as I am,” he joked. “We call each other ‘Fatso’ and we’re kidding each other all the time about how slow we are.”31 The hit gave the Orioles their ninth win in 10 games, maintaining the club’s seven-game AL East lead with 15 to play. On a day when Baltimore established a season attendance record, the fans insisted that Stefero take a curtain call.

One night later, he did it again, singling in the bottom of the 11th to deliver a second straight sudden death victory. His teammates mobbed him, and again the fans demanded that he return to the field. It was the 30th season of Orioles baseball in Baltimore, and the only previous player to stroke walk-off hits in consecutive games had been Dick Kryhoski in 1954.32 “It’s kind of a one-in-a-million chance to get to do this,” Stefero said. “I want to open some eyes here that I can hit in pressure situations.”33

“I like John ’cause he’s that squatty type catcher who can hit, like Yogi Berra,” remarked Orioles manager Joe Altobelli.34 The rookie wasn’t eligible for post-season play, but he received a partial playoff share and a 1983 World Series ring after Baltimore won it all in October.

In spring training 1984, Stefero worked with Orioles coach Elrod Hendricks, a former catcher, to become a more fluid defender. “At one point, he was concentrating on blocking balls and he’d do it his way until he was embarrassed,” Hendricks recalled. “But I see a big change now.”35

Stefero had largely overcome the behavior that nearly earned him a “head case” label.36 For example, he’d been benched for a couple games at Charlotte in 1982 for overruling some pitches manager Mark Wiley had called from the dugout.37 Even during his brief time in the majors, he admitted, “I thought I should be playing and got upset about it. I said some things I shouldn’t have and got some people mad.” He had a reputation for pouting after pop-ups and strikeouts. “I used to be that way, and even into my minor league career, but I really feel I got out of it,” he said.38

After playing only five games at Triple-A in early 1984, however, Stefero told Rochester’s Democrat and Chronicle, “I don’t know what to think. [Manager] Frank [Verdi)] just said he was sending me to A-ball.”39 One writer reported that a shouting match with Verdi preceded the catcher’s demotion. Apparently, something Stefero muttered in response to being asked to warm up a pitcher was misunderstood.40

He endured a miserable, lost season. In addition to a cracked kneecap, he broke the hamate bone in his right wrist on a checked swing. After batting only .209 with a single homer in 41 games with Hagerstown, he was promoted to Charlotte where he recovered his power but hit just .207. “I was hurt most of the season and I’m not sure if my managers believed I really was,” he remarked later.41

Stefero married his high school girlfriend Tammy, an aspiring cosmetologist, prior to the 1985 season. For the first time in four years, though, the Orioles didn’t invite him to spring training. He began the year back at Charlotte and, despite batting only .219, returned to Rochester in mid-season. Verdi had been fired, and Stefero performed well enough that “Tom Giordano told me I was the best catcher in the International League the second half of the season.” 42

When Stefero had first signed with the Orioles, Giordano observed, “Power-hitting catchers are a scarce commodity, especially guys who can hit from the left side as John can.”43 Though Stefero’s average at Rochester in ’85 was just .188, he’d clubbed three pinch-hit homers his first month back.44 He went deep 10 times in 128 at-bats.

As a non-roster invitee to spring training in 1986, Stefero impressed “new” Baltimore skipper Earl Weaver — lured out of retirement the previous June — with his power potential. When projected backup catcher Floyd Rayford chipped a bone in his thumb late in camp, Stefero made the Orioles’ Opening Day roster. On April 26 at Memorial Stadium, he smacked his first major league homer off Toronto relief ace Tom Henke — a three-run shot, as Weaver famously loved. Five weeks later, however, it was back to Rochester.

Stefero returned to the majors in July and started 31 games in the second half. He hit one more three-run homer, but took a beating late in the year — conked in the head by a Dave Winfield backswing against New York and leaving the field on a stretcher at Fenway Park after swallowing his tongue when a foul ball shattered his protective cup.45 On October 1, his line drive off the pitching elbow of Boston’s Roger Clemens ended the 1986 AL Cy Young winner’s final regular season start early. Though Clemens was able to make all five of his post-season starts, he won only one of them after a 24-4 campaign, causing some fans to blame Stefero when the Red Sox fell one game short of winning the World Series.

Three days after the end of the Fall Classic, Baltimore traded for the San Diego Padres’ Terry Kennedy, a three-time All-Star who was also a lefty-swinging catcher. The Orioles owed the Montreal Expos a player to be named later from a June deal, and sent Stefero to Canada in December to complete it. He acknowledged feeling disappointed to leave his hometown team but hoped it would be a good career move. “I don’t have any resentment,” he said. “They gave me an opportunity.”46

The Expos had already spent two years trying to fill the catching void created by the trade of Gary Carter. Stefero started a third of Montreal’s first 42 games in 1987 as both Mike Fitzgerald and Jeff Reed spent time on the disabled list, but he was shipped to Triple-A Indianapolis once the pair was sufficiently healthy to platoon. In his final big league plate appearance on May 24, Stefero was intentionally walked by Gossage in San Diego. The Expos let him go after the season.

Stefero went to spring training with the Cleveland Indians in 1988 but spent the entire season with the Triple-A Colorado Sky Sox. Though he saw the most action among all the catchers on the Pacific Coast League club that season, he didn’t produce enough to get another chance.

During 1989 spring training with the Indians, he called a pitchout on a rainy field against the Cubs. “My legs went one way and my arm went the other,” he recalled. “I tore a nerve in my elbow. I used to have a rocket arm, but I couldn’t throw and took a year off.” During his rehab, Stefero sold cars for Brown’s Toyota of Glen Burnie.

After signing a minor league deal with the Cubs in 1990, he returned to Charlotte, which had become a Chicago affiliate. He batted .190 with a solitary homer in 57 games, his final action in professional baseball. “I was on five, six, seven anti-inflammatories a day,” he explained. “They were making me sick and it was time to move on. It was depressing because I couldn’t get back to where I felt I should be.

“Baseball’s a very funny game, a very demanding game,” he reflected. “You play all of your life to get to MLB, but going up and down with injuries and trying to battle your way back, you lose your competitive edge, the belief that you’re the best.”

When the Orioles played their final game at Memorial Stadium on October 6, 1991, Stefero was one of dozens of former players on hand for the emotional closing ceremonies. “To be in that locker room was special, to see the talent in that room. I got to meet players I got to watch play when I was five or six years old,” he said.47 After the former Orioles took their old positions on the field one final time, he said, “Just to be out there with the talent that was on that field was a compliment to me.”48

In the fall of 1993, Stefero donned his catcher’s gear at Baltimore’s new ballpark, Camden Yards, replacing some of the actors in live action scenes filmed there for the Major League II movie. He also played occasionally in 30-and-over baseball leagues after leaving the pros. In 1998, the Glen Burnie-based Romano’s-Easton Braves traveled to Clearwater, Florida, for the Senior Baseball League’s championship tournament. Stefero helped them become the first team from Maryland to win it all.49

In 2000, he was inducted into the Anne Arundel County Sports Hall of Fame.50 Babe Phelps, part of that organization’s inaugural 1991 class, had also been a major league catcher from Odenton.

Both of Stefero’s marriages ended in divorce, and he says he has no plans for a third. Like many ballplayers, the hardships of a life filled with road trips took a toll. In 2008, he fathered his daughter Kayla with a longtime friend.

Meanwhile, he kept working at Brown’s Toyota of Glen Burnie, rising to Sales Manager, then General Sales Manager and, finally, President/General Manager. “Most athletes are go-getters, not content to sit around,” Stefero observed. “I don’t buy a car from anyone except him,” insists former teammate Ken Dixon. “I don’t even pick it out.”51

Stefero has been leading his team at Brown’s for an unprecedented two decades as of 2020, something he attributes to the team atmosphere at the family-owned business and lessons learned from playing for winners at so many levels of the sport he loved. While he misses the camaraderie he enjoyed in locker rooms and dugouts, Stefero is convinced that baseball “helped me in life, with being part of a team with goals.”

When he does get together with other former Orioles, players from different eras recognize each other as members of a unique brotherhood. Even when a decade or more passes between meetings, the conversations resume like it’s been a day.

Three decades after his last game in professional baseball, when Stefero watches baseball on TV, he recognizes Cardinals manager Mike Shildt as the batboy from his Double-A days in Charlotte. Shildt’s mother managed the team’s office. It’s one of many reminders of how the game connects people. “I wish more players remembered how it felt to be kids, looking up to them, getting autographs,” he said. “I had a very blessed career.”

Last revised: November 5, 2020

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to John Stefero (telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, September 9, 2020).

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com, and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Zach Sparks, “Brown’s Toyota President John Stefero Recalls His Days as an Orioles Catcher,” Pasadena Voice, April 20, 2016, https://www.pasadenavoice.com/stories/browns-toyota-president-john-stefero-recalls-his-days-as-an-orioles-catcher,14152? (last accessed September 23, 2020).

2 Kathy Frazier, “O’s Farewell Hits Home,” Baltimore Sun, October 9, 1991: 8.

3 Pat O’Malley, “For Odenton’s Stefero, Signing with O’s is Dream Come True,” Baltimore Sun, July 1, 1979: AL4.

4 O’Malley

5 Unless otherwise cited, all John Stefero quotes are from his telephone interview with Malcolm Allen, September 9, 2020.

6 Pat O’Malley, “For the County Sports Smarty; it’s Pat’s Quickie Quiz,” Baltimore Sun, January 22, 1987: 13.

7 O’Malley, “For Odenton’s Stefero, Signing with O’s is Dream Come True.”

8 O’Malley

9 O’Malley

10 O’Malley

11 O’Malley

12 Pat O’Malley, “Sports Shorts,” Baltimore Sun, July 15, 1979: AR11

13 Pat O’Malley, “Players Contrast Big League Dreams, Bush League Realities,” Baltimore Sun, September 23, 1979: 214.

14 Pat O’Malley, “Stefero’s in Uniform at Stadium, But He’s Not a Big Leaguer Yet,” Baltimore Sun, September 21,1980: AS14.

15 O’Malley,

16 Pat O’Malley, “Stefero Bids ‘Adios’ to Winter Baseball,” Baltimore Sun, March 15, 1981: AS3.

17 1983 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 157.

18 “Stefero Sparkles for Carolina North Stars,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1981: 41.

19 Pat O’Malley, “Stefero Making His Mark at Hagerstown,” Baltimore Sun, July 5, 1981: AS4.

20 “Stefero Crosses Up Strategy,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1982: 43.

21 “Cooked Goose,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1982: 40.

22 “Stefero Crosses Up Strategy.”

23 Pat O’Malley, “Stefero’s Return Has Been Worth the Wait,” Baltimore Sun, June 29, 1983: AS7.

24 1986 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 220.

25 “Southern League All Stars,” The Sporting News, June 7, 1983: 48.

26 Ray Parrillo, “Stefero Surprised, But Elated,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1983: C2.

27 “Comebacks Becoming Habit for Birds,” Santa Fe New Mexican, September 20, 1983: 11.

28 1984 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 183.

29 Greg Boeck, “Red Wings Shaping Up; Bradley Isn’t,” Democrat and Chronicle, March 19, 1984: 25.

3030] Bob Greene, “Rookie Comes Through as Orioles Beat Brewers,” Index-Journal (Greenwood, South Carolina), September 19, 1983: 8.

31 Bill Free, “Orioles Win, Set Attendance Record,” Baltimore Sun, September 19, 1983: C1.

32 1986 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 157.

33 “Comebacks Becoming Habit for Birds.”

34 Thomas Boswell, “Rookie Stefero; 2 Games as Orioles’ Catch of Day,” Washington Post, September 21, 1983: D5.

35 Kent Baker, Orioles Fall, 4-1,” Baltimore Sun, March 7,1984: F1.

36 Pat O’Malley, “Glen Burnie’s John Stefero May Surprise Orioles,” Baltimore Sun, February 16, 1986: 16.

3737] “Not the Mustache,” The Sporting News, May 17, 1982: 39.

38 O’Malley, “Stefero’s Return Has Been Worth the Wait.”

39 John Kolomic, “Stefero, Snell Demoted as Verdi Shakes Wings,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), May 3, 1984: 4D.

40 Pat O’Malley, “County Players Face Hurdles in Quest for Big Leagues,” Baltimore Sun, June 23, 1985: AS15.

41 O’Malley

42 O’Malley, “Glen Burnie’s John Stefero May Surprise Orioles.”

43 O’Malley, “For Odenton’s Stefero, Signing with O’s is Dream Come True.”

44 1986 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 220.

45 Pat O’Malley, “Orioles Stefero is Throwback to Glory Days,” Baltimore Sun, October 5, 1986: 20.

46 Chris Marti, “Down on the Farm,” Baltimore Sun, July 19, 1987: 22.

47 Frazier, “O’s Farewell Hits Home.”

48 Frazier

49 Pat O’Malley, “County Braves Capture U.S. 30-plus Baseball Title,” Baltimore Sun, November 12, 1998: 8D.

50 Pat O’Malley, “Ciccarone, Stefero Head Picks for Hall,” Baltimore Sun, September 24, 2000: 25D.

51 Ken Dixon, telephone interview with author, September 12, 2020.

Full Name

John Robert Stefero

Born

September 22, 1959 at Sumter, SC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.