October 12, 1916: Red Sox claim championship on adopted turf

It was Columbus Day and the biggest crowd of the 1916 World Series. The Red Sox led the Brooklyn Robins three games to one. Some 43,620 came to Boston’s Braves Field to see if the Red Sox could win their second world championship in a row. Brooklyn crowds had been only half the size of Boston’s, despite it being their team’s first appearance in a World Series. Owner Charles Ebbets charged much higher prices than were customary at the time – all the way up to $5.00. And the weather was very cold. It may be, too, that few in the borough had thought the Brooklyns had much of a chance to win.

It was Columbus Day and the biggest crowd of the 1916 World Series. The Red Sox led the Brooklyn Robins three games to one. Some 43,620 came to Boston’s Braves Field to see if the Red Sox could win their second world championship in a row. Brooklyn crowds had been only half the size of Boston’s, despite it being their team’s first appearance in a World Series. Owner Charles Ebbets charged much higher prices than were customary at the time – all the way up to $5.00. And the weather was very cold. It may be, too, that few in the borough had thought the Brooklyns had much of a chance to win.

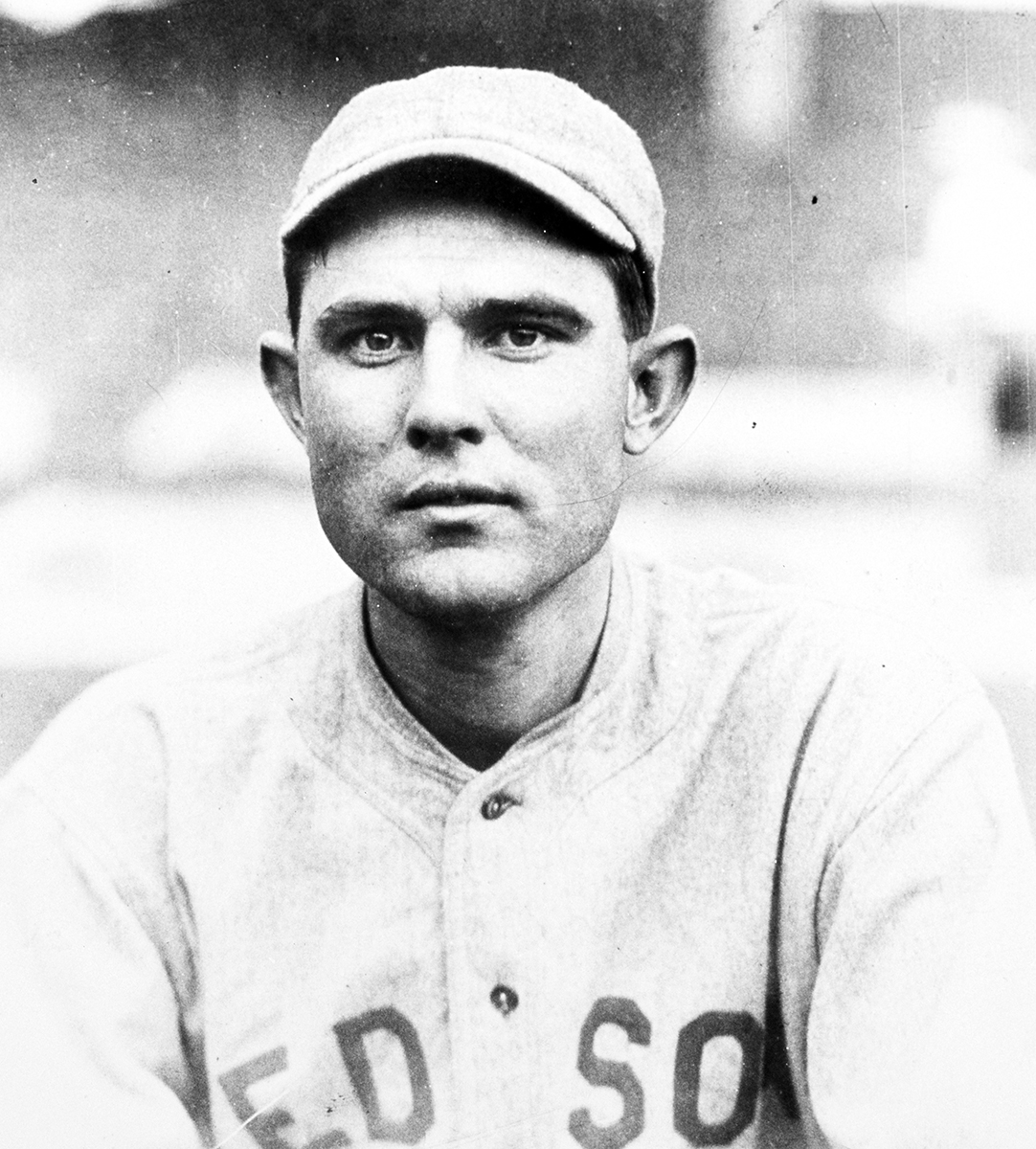

The fifth game, in Boston, saw Brooklyn’s Jeff Pfeffer start, facing Game One winner Ernie Shore. For Pfeffer, it was his fourth appearance of the Series. He’d thrown the last inning in relief of Rube Marquard in Game One, pitched the last 2⅔ innings saving Game Three for Jack Coombs, and had pinch-hit for Rube Marquard in Game Four (striking out) before Larry Cheney came in to pitch. Pfeffer had been a formidable 25-11 in the 1916 regular season, with a 1.92 ERA.

Red Sox manager Bill Carrigan had already announced that he would retire after the World Series.

For the fourth game in a row, Brooklyn scored first – a single run, without benefit of a hit, in the top of the second. George Cutshaw walked on four pitches and then advanced one base at a time on Mike Mowrey’s sacrifice, Ivy Olson’s high bouncing grounder to third that Sox third baseman Larry Gardner hauled down, and a passed ball charged to catch Hick Cady.

In no time the Red Sox countered and tied the score in the bottom of the second when Duffy Lewis hit a one-out triple down the left-field line and Gardner flied one just barely deep enough to left that Lewis was able to tag and score when Zack Wheat’s throw went wide.

After the Robins (some accounts were already calling them the Dodgers, though they were more frequently termed the Robins in reference to manager Wilbert Robinson) failed to get the ball out of the infield in the top of the third, the Red Sox took advantage of their next opportunity to score as well.

Cady singled to lead off the bottom of the third. Ernie Shore attempted a sacrifice bunt, but fouled out to Brooklyn catcher Chief Meyers. Pfeffer missed with four in a row and walked Harry Hooper. Red Sox second baseman Hal Janvrin hit a ball to shortstop Ivy Olson that looked like a sure double play, but Olson tried to rush the throw and couldn’t maintain his grip on it. After he finally corralled it, his only play was to first – but the ball flew out to right field, enabling Cady to score and Hooper to reach third, Janvrin stopping safe on first. Janny was caught stealing, but center fielder Chick Shorten then singled up the middle and into center field, and Hooper trotted home. Shorten was then caught stealing, too, the second aggressive Red Sox baserunner erased in the inning.

Brooklyn finally got its first hit of the game in the fifth, a meaningless single into center field by Chief Meyers, but it came with two outs and Pfeffer was up next. He grounded out, third to first. And, as if to punish the Robins for presuming to get a base hit, the Red Sox added an insurance run when Hooper singled and Janvrin doubled, both of them first-pitch-swinging – a strategy employed by several Sox throughout the game. It was 4-1, Red Sox, after five.

Neither team scored again. Brooklyn added one single in the seventh and one in the ninth. A subsequent error in the seventh resulted in Robins runners on second and third, but there were two outs and Meyers hit one back to Shore, who threw him out at first to retire the side. Casey Stengel singled to lead off the Brooklyn ninth, but Shore buckled down and didn’t let the ball out of the infield, striking out Wheat and getting Cutshaw to ground out to second, forcing Stengel. Mowrey was up. While the band was playing “This Is the End of a Perfect Day,” Shore induced Mowrey to hit a pop fly to Everett Scott at short for the third and final out.

Shore walked off the mound triumphant as the Red Sox won the game, 4-1, and captured their fourth world championship.

Shore had his famous “down ball” working and allowed just “three measly hits,”1 with just one base on balls, the only run an unearned one, and won his second game of the Series while the Red Sox won their second Series in succession.

Because they had borrowed Braves Field so they could pack in more fans, the Red Sox had taken the 1916 World Series with ease, despite never once playing on their true home field.

The New York Times column on the game said acidly of the 4-1 final that if the score “had been 40 to 1 it would have represented more accurately the respective merits of the two contending teams.”2 The game was said to be so lacking in drama that even the hometown fans didn’t get worked up during the competition. The Times said the contest “resembled a tug of war between an elephant and a gold fish.”3

Boston fans were so jaded that Wallace Goldsmith’s sports-page cartoon of the game in the Globe depicted a tradition apparently more longstanding than heretofore appreciated – fans on the first-base side were “so sure of the outcome that it amused itself batting toy balloons about.”4 Not everyone who had wanted to get into Braves Field had, however. The Boston Herald observed, “While the game was in progress an army clogged the streets around the park, a disappointed army, because the gates had been closed and the field was filled up.”5

At the very end, though, there arose such a loud shout from all those present that its effect was all the more startling, given their quiescence throughout. Winning the World Series was apparently still a big thing in Boston, though the Red Sox had now won three of the last five played. The masses flocked to the field and marched around behind the Royal Rooters band. “After the cheering and the marching, the gathered thousands wended out of the vast closure, smiling and happy.”6

Widely syndicated columnist Hugh Fullerton proposed abolishing the World Series. The American League was superior, he wrote, and the Brooklyn “team was licked, beaten, and dogging before it went to the park. … Brooklyn dogged it.” He claimed they’d held a team meeting before the game to decide how to divide the losers’ share, a telling and self-fulfilling attitude. Overriding the play of the losers was Fullerton’s feeling that “baseball has ceased to be a sport and has become a commercial enterprise.” The players were, he felt, more interested in the money than the result on the field. Fullerton closed his column recounting what Christy Mathewson had told him: “I don’t know whether the best team won or not, but I am satisfied that the worst team lost. You’ve got to give it to Brooklyn – they finished the game – and it looked to me as if that was about all they were trying to do.”7

Postscript on Ernie Shore: Ernie Shore’s contract had been purchased by the Red Sox on July 9, 1914, the very same day the Red Sox bought Babe Ruth. The year after the 1916 World Series, Shore pitched as perfect a game as one could ask for – on June 23, 1917. Ruth started the game but became so furious when the home-plate umpire ruled that he’d walked the first batter that Ruth was ejected from the game. Shore came in with the runner on first, and then retired 27 men in order, the first one being the baserunner on first who was picked off. Today Shore’s game is considered an “unofficial” perfect game. After a good year in 1917, Shore spent 1918 in the Navy before being traded to the New York Yankees that December, but his better years were behind him.

Sources

This account is adapted from Bill Nowlin and Jim Prime, “From the Babe to the Beards” (New York: Sports Publishing, 2014), itself an adaptation of the two authors’ “The Red Sox World Series Encyclopedia,” published by Rounder Books in 2008. This article also appeared in “Braves Field: Memorable Moments at Boston’s Lost Diamond” (SABR, 2015), edited by Bill Nowlin and Bob Brady. To read more articles from this book, click here.

Box scores for this game can be seen on baseball-reference.com, and retrosheet.org at:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/BOS/BOS191610120.shtml

http://www.retrosheet.org/boxesetc/1916/B10120BOS1916.htm

Notes

1Boston Herald, October 13, 1916.

2New York Times, October 13, 1916.

3 Ibid.

4 Boston Globe, October 13, 1916.

5Boston Herald, October 13, 1916.

6 Ibid. The Herald suggested that one of the happiest might have been Wilbert Robinson, because his Brooklyn team wouldn’t have to face the Red Sox again.

7New York Times, October 13, 1996.

Additional Stats

Boston Red Sox 4

Brooklyn Robins 1

Game 5, WS

Braves Field

Boston, MA

Box Score + PBP:

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.