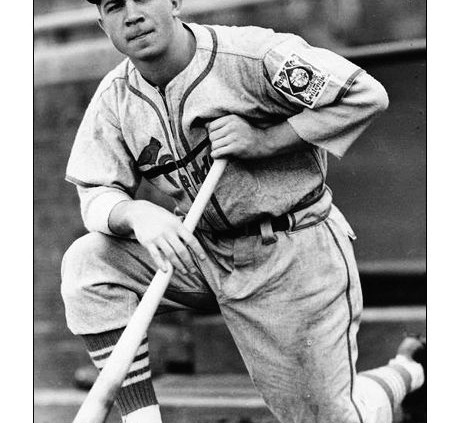

Johnny Hopp

He grew up in a small Nebraska town with a high school that did not field a baseball team. He signed professionally with an organization that notoriously signed hundreds of prospects with the expectation that such quantity would yield quality. Yet Johnny Hopp diligently overcame these obstacles to carve out a successful 14-year career in the major leagues, earning four World Series championship rings in the process.

He grew up in a small Nebraska town with a high school that did not field a baseball team. He signed professionally with an organization that notoriously signed hundreds of prospects with the expectation that such quantity would yield quality. Yet Johnny Hopp diligently overcame these obstacles to carve out a successful 14-year career in the major leagues, earning four World Series championship rings in the process.

John Leonard Hopp was born on July 18, 1916, in Hastings, Nebraska. He was one of nine children raised by Johannes (John) Hopp and Alice Elisabeth Schreiner. Both parents were of German ancestry and immigrated to the United States from the Volga River region of Russia.1 Johannes Hopp supported his large family by raising chickens on his farm and selling them to markets in the Midwest and East. In his later years he owned and operated Hopp’s Tavern, a local bar and restaurant.2 The six Hopp boys were all interested in athletics. Harry Hopp was a football star at the University of Nebraska and played professionally for the Detroit Lions as well as three teams in the All-America Football Conference.3 Another brother, Clifford, was a skilled American Legion baseball player who earned a tryout with the Boston Braves.4

Johnny Hopp played football and basketball and ran track at Hastings High School, graduating in 1934. The only baseball opportunities available in Hastings, a farming community of approximately 10,000, were the sandlots of Adams County and American Legion ball. He attended Hastings College for one year, and played semi-pro ball for a team in Carroll, Iowa, once facing a team from Templeton, Iowa, that featured a hard-throwing teenager named Bob Feller.5 A left-handed hitter with occasional power and speed on the bases, Hopp impressed Joe McDermott, a Nebraska-based manager and part-time scout for the St. Louis Cardinals, and signed a contract with the organization in 1936.

A year earlier, Hopp had married 18-year-old Marian Grace Simpson, his sweetheart from high school. The couple was married for 33 years until her death in 1968. A year later, Hopp married Sarah Grasmick Leis and they remained together throughout the rest of his life.6

Assigned to the Norfolk Elks of the Class D Nebraska State League in 1936, the 5’10”, 170-pound Hopp had an outstanding first season as a pro, batting .361 with 26 home runs, 24 doubles and a .661 slugging percentage. He also stole 36 bases and hit safely in 26 consecutive games. Under the auspices of general manager Branch Rickey, generally considered the father of the baseball farm system, the Cardinals had affiliate agreements in place with a staggering 24 professional clubs featuring more than 400 prospects. It took a terrific season like Hopp’s to gain the parent club’s attention. He was promoted to the Class AA Rochester Red Wings for 1937.

Hopp continued to show considerable promise. In the season opener at Jersey City, he hit the first home run in the brand-new Roosevelt Stadium before more than 30,000 fans.7 As the starting center fielder, he batted .307 and collected 162 hits in 141 games, including 51 for extra bases. But the solid performance didn’t guarantee him any upward movement in the organization’s crowded depth chart, and a sore left throwing arm developed late in the year contributed to the Cardinals’ decision to send him back to Rochester for another season. His second year with the Red Wings was consistent with his first. By now starting to be referred to by the colorful nickname “Hippity,” Hopp hit .299 with 21 doubles, 16 stolen bases and 48 runs batted in.

The sore arm continued to nag him during the year, but it would ultimately pay dividends long term. Worried about his future as an outfielder, the Cardinals decided to send Hopp to Houston of the Texas League and asked him to learn to play first base. Hopp readily agreed and began the 1939 season as the regular first baseman. He committed 18 errors while learning the position but continued his development as a line-drive hitter who was aggressive on the base paths. He was hitting .312 with 28 doubles and 15 triples when the Cardinals called him up in September.

Hopp’s major league debut occurred as a pinch-runner for Johnny Mize in the ninth inning of a 7-2 loss to the Giants at Sportsman’s Park on September 18, 1939. His first big-league hit was a two-run pinch-hit single three days later against Brooklyn that tied the game at 4-4 in an eventual 6-5 Cardinal victory. Later that evening, Hopp was notified that his wife had given birth to a daughter the couple named Terrill.8 A son, John Cotney Hopp, would be born in 1944.9 The boy’s middle name came from his father’s nickname, which was inspired by bright blond “cotton top” hair.

Invited to spring training by the Cardinals, Hopp agreed to do whatever he could to make the ball club and help the Cards. Assessing the team’s unsettled outfield beyond Terry Moore and Enos Slaughter, J. Roy Stockton wrote in The Sporting News, “Johnny Hopp is adding value by his ability to play first base and clout the ball as a pinch-swinger.”10 Hopp made the team and spent the 1940 season in St. Louis primarily backing up Moore in center field and Mize at first base. In 152 at-bats he hit .270, a figure that was dampened by going 4-for-23 as a pinch-hitter.

Billy Southworth had finished the season as the St. Louis manager after Ray Blades was let go following a 14-24-1 start. Southworth favored a roster of good contact hitters and emphasized sound defense and efficient pitching. With Rickey’s farm system producing young products like Hopp, Slaughter, and infielders Marty Marion and Frank (Creepy) Crespi, the Cardinals made a serious run at the 1941 National League pennant. They won 97 games, finishing two-and-a-half games behind the Brooklyn Dodgers. Inserted as the regular left fielder, Hopp drove in 50 runs and ranked fifth in the NL with 15 stolen bases. But he struggled at the plate in September with the pennant on the line. Among the league batting leaders at the start of September, he saw his average drop 30 points during the month to a season-ending .303.

Still, the Cardinals decided Hopp’s offensive skills were a better fit than the slugging, but slow, Mize. In December, the Cardinals traded Mize to the New York Giants for cash and three players.11 Sidelined in May with a broken thumb, Hopp began the season dismally. “Hopp is far down in the batting list, whereas a year ago he was a ball of fire,” The Sporting News reported.12 As late as July 10 he was hitting below .200. But he managed a resurgence at the plate that included a mid-July 5-for-10 effort in a three-game sweep of the Braves. By season’s end, Hopp was at .258 with 14 stolen bases. Twenty-one of his 37 RBIs came in August and September. His revived hitting helped St. Louis win 38 of its last 44 games to earn the club’s first pennant since 1934. He started all five games of the Cardinals’ stunning victory over the New York Yankees in the World Series but was limited to three singles in 17 at-bats.

By 1943, baseball owners and general managers faced the reality that the need for greater numbers of troops for American armed forces in World War II would have significant impacts on all major league rosters. Over the winter, the Cardinals learned that Slaughter, Crespi, Moore and star pitcher Johnny Beazley would all enter the armed services.13 Now 27 years old with a family to support, Hopp had yet to hear from his draft board when he traveled to Cairo, Illinois, where the Cardinals were holding spring training.

It was to be another season of nagging injuries and sub-par results at the plate for Hopp. After coming in as a pinch-runner on April 29, he was sidelined for 11 games with debilitating back pain diagnosed as neuralgia and attributed to injuries suffered during his high school football days.14 He lost his starting first base job to Ray Sanders in June and filled a utility role the rest of the season, usually playing left field against right-handers. Appearing in only 91 games, he batted a meager .224 with two homers and 25 RBIs. He started one game in the Cardinals’ five-game loss to the Yankees in the 1943 World Series.

The following spring it appeared Hopp would finally be called to serve in the armed forces. With the Allies planning the invasion of Europe that would come on June 6, thousands of previously bypassed men now received their notices. In March, The Sporting News surmised that Hopp would be classified as 1-A.15 He was ordered to take his physical in his hometown of Hastings. In April it was reported that Hopp would be summoned for a pre-induction examination at Jackson Barracks, Missouri, the first week in May. A week after his exam, Hopp was officially classified 4-F because of his recurring back troubles.16

Billy Southworth was pleased to still have Hopp, as well as Stan Musial, Marty Marion, Whitey Kurowski and the Cooper brothers (Mort and Walker) for 1944. With such a nucleus, St. Louis was an overwhelming favorite to win a third consecutive pennant. This time, Hopp played an important role, enjoying the finest season of his career. On June 4 he collected three hits and a stolen base before pulling a leg muscle. Briefly sidelined, he returned to raise his average above .300 and remained there for the rest of the season. On July 9, he went 3-for-4 with a double and a triple, and he stole home in a 9-0 win over the Braves. On September 21, he smacked three doubles, again vs. the Braves.

“Hopp looks like the most improved player in the National League this year,” wrote Fred Lieb. “Johnny runs singles into doubles, doubles into triples, and how that jackrabbit can flit from first to third on somebody else’s single.”17 Replacing Moore as the regular center fielder, Hopp finished with a robust .336 batting average, good for fourth in the National League. He belted 35 doubles with 11 homers and had 72 runs batted in. His OPS was a lofty .903 and his WAR figure was 5.8.

“I’ve been meeting the ball well, getting my share of hits, and I guess that gives a fellow a lot of confidence,” Hopp said as the Cardinals prepared to meet the surprising Browns in an all-St. Louis World Series.18 Unfortunately for the native Nebraskan, his bat turned cold yet again in the World Series. Hopp finished 5-for-27 at the plate against the Browns. (In 50 career at-bats scattered across five World Series, Hopp hit .160 and failed to drive in a run.) Commenting on the Series in The Sporting News, Leo Durocher wrote, “Speaking of Hopp, he had a bad Series. Very bad. I figured him to be a leader. He got into the Series labeled a potential star and gave up on himself at the close.”19 Durocher’s criticism ignored an outstanding catch Hopp made in deep right-center in the fourth game that saved a run and helped the Cardinals even the Series, which they went on to win in six games.

Hopp followed up his big 1944 regular season by putting together another solid effort at the plate in 1945. Although his batting average dropped to .289, he posted a .758 OPS, stole 14 bases, drew 49 walks, and struck out only 24 times in 505 plate appearances. He received some support for the Most Valuable Player award, finishing 15th in the voting, his third top-20 finish in five years. The Cardinals won 95 games but finished runner-up to the Cubs in the National League despite owning a 16-6 advantage in head-to-head competition vs. Chicago.

With both the war and the Cardinals’ run of three straight pennants concluded, big changes were in the offing in St. Louis. Billy Southworth asked for his release to become the manager of the Boston Braves. Eventually, Southworth and the Braves would acquire a number of ex-Cardinals including Mort Cooper, Ray Sanders, Ernie White and Ken O’Dea. On February 5, 1946, the Braves added Hopp to that group, sending St. Louis infielder Eddie Joost and $40,000 in cash.20

Disappointed as he may have been to leave the Midwest and the only organization he had known, Hopp didn’t let the trade bother him on the playing field. Splitting time almost evenly between first base and the outfield, he made a run at the league batting championship, eventually finishing second to ex-teammate Musial. On May 5, he rapped a pair of home runs and three singles in a five-hit performance against the Cardinals. Named to his only All-Star Game, he started in center field and went 1-for-2 in the game at Fenway Park, one of three NL hits in a 12-0 loss to the American League.

Nagging injuries curtailed him to 129 games, but he compiled a .333 batting average with 21 stolen bases (third in the NL) and helped the Braves have their first winning season since 1938. “One of the most encouraging features of the Braves’ late-season drive has been the batting comeback of Johnny Hopp,” wrote Howell Stevens in The Sporting News. “The Human Motorcycle even stole two bases in one inning (September 14 vs. Pittsburgh).”21

Turning 31 years old in July 1947, Hopp managed to stay healthy most of the year and produced another typical season, hitting .288 while stealing 13 bases for a Boston team that swiped only 58 all season. Looking for more power, the Braves decided to package Hopp in a trade with the Pirates to acquire switch-hitting outfielder Jim Russell from Pittsburgh. “It’s up to Hopp to prove that [Pirate manager] Bill Meyer knew what he was doing when he gave up Russell for him,” analyzed one national writer.22

Used in all three outfield spots, first base and increasingly as a pinch-hitter, Hopp hit .278 in 1948. His 12 triples ranked second in the league. He became known as a clutch pinch-hitter, batting .500 (7-for-14) for the year. In seven pinch-hit appearances in August, Hopp collected a walk and five hits, including two doubles and a pair of triples.

Hopp struggled at the beginning of his second season in Pittsburgh. With his average at an anemic .218, he was traded to the Dodgers on May 18 for outfielder Marvin Rackley. Brooklyn president Branch Rickey, who had approved signing Hopp to a professional contract back in 1935, wanted insurance for Gil Hodges at first base. “He’ll score for you like Jackie Robinson, not just stand around on the bases,” said Brooklyn manager Burt Shotton of Hopp. “I’m tickled to death to have him.”23 But used primarily as a pinch-hitter, Hopp had a miserable time in Brooklyn, appearing in eight games and going hitless in 14 at-bats. However, a somewhat bizarre circumstance served to rescue his season.

Pirates president Frank McKinney soon began complaining that Rackley was damaged goods when Rickey and the Dodgers made the deal. Although Rackley hit well in his 11 games in Pittsburgh (11-for-35), McKinney said he had an injured throwing arm, and the Pirates could not play him in the outfield. Eventually, McKinney’s public complaints touched a nerve with the proud Rickey. Brooklyn offered to cancel the trade, and when Pittsburgh agreed on June 7, Hopp was once again a member of the Pirates.

In his second game back with Pittsburgh, Hopp had four hits in an extra-inning game with the Phillies. Starting July 14, he hit safely in 20 of 22 games, including 14 in a row. “Johnny Hopp is playing the best ball of his career,” wrote Les Biederman in The Sporting News. “He’s boosted his average more than 50 points.”24 He was sidelined with a broken nose in early August but bounced back strong. In a two-game series against the Dodgers in mid-September, Hopp showed Brooklyn what might have been, going 5-for-9 with a double and a homer, scoring four runs and driving in three. The torrid second half enabled Hopp to wind up with his fourth full season above .300 (.306).

Entering 1950, Hopp was on the verge of turning 34 with a history of back ailments and assorted minor injuries. Few baseball executives considered him an everyday player anymore. But he proved he still had plenty of value. Destined to finish last in the NL, the Pirates began using him almost exclusively as a platoon first baseman and pinch-hitter. Hopp showed what kind of professional hitter he was, shrugging off the inconsistent playing time to sting the ball as well as he ever had. On May 14 in the second game of a doubleheader at Wrigley Field, Hopp went 6-for-6, including a pair of home runs in a 16-9 thrashing of the Cubs. His second homer was a ninth-inning blast into the right-center bleachers after which, “even the Cubs doffed their caps to this brilliant star,” reported the Pittsburgh Press.25

Hopp’s veteran experience and productivity attracted the attention of the New York Yankees, who were involved in a much tighter-than-expected pennant race with the Tigers and Red Sox. On September 5, New York announced that it had obtained Hopp in a cash purchase after the player had cleared National League waivers. American League teams were irate and an editorial in The Sporting News opined, “One does not pick up a .340 hitter, such as Hopp, for a mere $10,000,” and proceeded to question the integrity of the whole waiver process.26 Yankee manager Casey Stengel twisted the knife a bit by stating, “I have a hunch the Hopp deal will make National League people sore before long.”27

Sent up as a pinch-hitter with the bases loaded in the ninth inning of a 1-1 contest at Sportsman’s Park on September 17, Hopp cracked a grand slam in an eventual 6-1 Yankee victory over the Browns. The Yankees wound up winning the American League flag by three games over Detroit. Hopp did his part down the stretch, hitting .333 in 19 games for the Bronx Bombers while filling in at first base and left field. Selected over longtime-Yankee Tommy Henrich as the final position player eligible for the World Series, Hopp was hitless in two at-bats in the Yanks’ four-game sweep of the Phillies.

He spent the entire 1951 campaign with the Yankees but was relegated to only 25 games in the field. Hopp became the Yanks’ top left-handed pinch-hitter, fitting in well with Stengel’s penchant for platooning his players. But his bat was slowing down, and he hit only .206 in 63 at-bats. After a poor start in 15 games the next season, the Yankees released him on May 22.28 The Tigers signed him 10 days later for the balance of his 1952 salary — $12,000. “I had 15 offers,” said Hopp, who explained that Yankee teammates Allie Reynolds and Ed Lopat had advised him to sign with Detroit. “I’m convinced I can help this club.”29

It turned out that Hopp’s ability to consistently hit line drives was rapidly fading. He batted .217 in 42 games with the Tigers, winding up his 14th — and final — season in the big leagues below .200. He finished his career as a .296 hitter with 458 RBIs and 128 stolen bases. He made appearances in five World Series and played on four championship teams.

Hopp spent 1953 immersing himself in operating a golf driving range in his hometown of Hastings. In October, he was contacted by Tiger manager Fred Hutchinson and offered a position as the team’s third base coach. He accepted and spent the ‘54 season with the Tigers. When Hutchinson was let go in favor of Bucky Harris, Hopp was out of a job and spent part of the next season managing a Class C team in Grand Forks, North Dakota. In 1956, when Hutchinson was appointed manager of the Cardinals, Hopp rejoined him to coach third base and spent his last year in a professional baseball uniform working for the team that gave him his start. He was released from the coaching staff at the end of the season and moved back to Hastings.

Hopp soon obtained a position in administration for the Kansas-Nebraska Natural Gas Company, traveling the state of Nebraska doing public relations work, writing a newsletter, and conducting youth clinics on behalf of the company. He was an avid outdoorsman, playing golf and taking pleasure in hunting pheasants and rabbits along the Platte River. “That’s one reason I live here,” he told Sports Illustrated in 1970. “Fifteen minutes to the hunting and 15 minutes to the fishing.”30

Reflecting on his career, Hopp said, “I dreaded the day I couldn’t play. I couldn’t imagine not playing ball anymore. I’d be lying to you if I said I didn’t miss it, but life goes on.”31

He kept an extensive collection of baseball memorabilia, including autographed bats and uniforms, some of which he donated to the Hastings Museum.32 In 1997 at the age of 81, he had the pleasure of being inducted into the Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame.33 Another honor was bestowed upon him when the state of Nebraska named its annual American Legion playoff competition the Johnny Hopp Tournament.

Johnny Hopp passed away on June 1, 2003, at the age of 86 in Scottsbluff, Nebraska. He was buried near the gravesites of his parents and first wife at Parkview Cemetery in his beloved hometown of Hastings.34

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Norman Macht and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

All statistical matter was taken from the website www.baseball-reference.com. In addition to the other references cited, the writer used the 1970 Baseball Dope Book, published by The Sporting News. All other sources are shown in the Notes.

Notes

1 “The Volga Germans,” https://www.volgagermans.org/who-are-volga-germans/culture/biographies/hopp-john-leonard-johnnycotney.

2 John Underwood, “A Brief Search for America,” Sports Illustrated, May 4, 1970: 71.

3 Total Football II (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999), 910.

4 “Another Hopp for Braves,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1946: 18.

5 George Wiswell, “Johnny Hopp from Hastings,” Baseball Digest, May 1945: 36.

6 Find a Grave website, “Johnny Hopp,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7537055/johnny-hopp

7 Wiswell, “Johnny Hopp from Hastings,” Baseball Digest, May 1945: 37.

8 Dick Farrington, “Johnny Hopp, St. Louis’ New Gas Houser, Has Cardinal Officials Humming ‘Hippity Hopp to the Pennant Shop,’” The Sporting News, August 21, 1941: 3.

9 Find a Grave website, “Johnny Hopp,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7537055/johnny-hopp.

10 J. Roy Stockton, “Cards Look Stronger All Down the Line,” The Sporting News, March 14, 1940: 3.

11 Joseph L. Reichler, editor, The Baseball Encyclopedia, seventh edition, (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1988), 2,536.

12 The Sporting News, July 9, 1942: 2.

13 Fred Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G.P. Putnam Sons, 1947), 203.

14 Farrington, “Ailing Arm Elbows M. Cooper Out Again,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1943: 2.

15 Lieb, “Bars Put Up for Holdouts at Card Camp,” The Sporting News, March 23, 1944: 9.

16 The Sporting News, May 11, 1944: 13.

17 Lieb, “Hats Off,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1944: 17.

18 Paul A. Rickart, “Hopp’s Johnny-On-The-Spot for Cards,” The Sporting News, October 5, 1944: 11.

19 J.G. Taylor Spink, “Looping the Loops,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1944: 1-2.

20 Joseph L. Reichler, editor, The Baseball Encyclopedia, seventh edition, (New York: MacMillan Publishing Company, 1988), 2440.

21 Howell Stevens, “Hub Hails Billy for First-Year Job on Braves,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1946: 8.

22 Dan Daniel, “Off-Season Changes Put Many on the Spot,” The Sporting News, March 3, 1948: 3.

23 Harold C. Burr, “Rickey Pads Bankroll While Cutting Brooks,” The Sporting News, May 25, 1949: 11-12.

24 Biederman, “Hopp’s Hustle Helps Spark Bucco Spurt,” The Sporting News, August 3, 1949: 14.

25 Biederman, “Hopped-Up Pirates Beat Cubs Twice,” Pittsburgh Press, May 15, 1950: 22.

26 “Confidence, the Cornerstone of O.B.” The Sporting News, September 20, 1950: 10.

27 Daniel, “Casey Sees Hopp Deal as Another Mize Purchase,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1950: 4.

28 “Yanks Release Johnny Hopp, Former Pirate,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, May 23, 1952: 25.

29 “Tigers Sign Veteran Hopp,” The Sporting News, June 11, 1952: 21.

30 Underwood, “A Brief Search for America,” Sports Illustrated, May 4, 1970: 71.

31 Underwood, “A Brief Search for America.”

32 Hastings Museum website, https://hastingsmuseum.org/programs-events/summer-fun-2021/.

33 Nebraska High School Sports Hall of Fame, Johnny Hopp – Hastings https://nebhalloffame.org/johnny-hopp-hastings/?id=2.

34 Find a Grave website, “Johnny Hopp,” https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/7537055/johnny-hopp.

Full Name

John Leonard Hopp

Born

July 18, 1916 at Hastings, NE (USA)

Died

June 1, 2003 at Scottsbluff, NE (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.