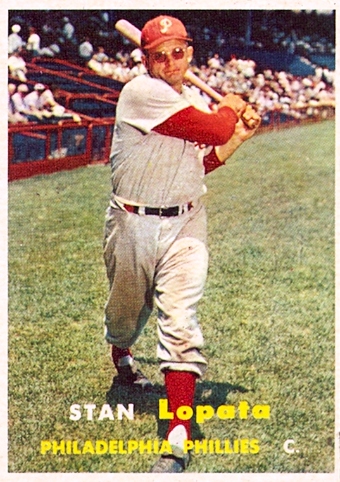

Stan Lopata

On a road trip in 1954 with the Philadelphia Phillies, Stan Lopata, called “Big Stash” in the press and Lop by his teammates, was having trouble making contact with the ball. He and his roommate on the Phillies, outfielder Johnny Wyrostek, had just finished eating breakfast at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. While Lopata paid the check, Wyrostek ran into Rogers Hornsby in the lobby of the hotel. Hornsby was by then out of baseball, having managed the Cincinnati Reds the year before, but was living at the hotel. As Lopata walked up, Wyrostek asked Hornsby about his buddy, Lopata said, “because I was having trouble getting my bat on the ball.”

On a road trip in 1954 with the Philadelphia Phillies, Stan Lopata, called “Big Stash” in the press and Lop by his teammates, was having trouble making contact with the ball. He and his roommate on the Phillies, outfielder Johnny Wyrostek, had just finished eating breakfast at the Edgewater Beach Hotel in Chicago. While Lopata paid the check, Wyrostek ran into Rogers Hornsby in the lobby of the hotel. Hornsby was by then out of baseball, having managed the Cincinnati Reds the year before, but was living at the hotel. As Lopata walked up, Wyrostek asked Hornsby about his buddy, Lopata said, “because I was having trouble getting my bat on the ball.”

Wyrostek said, “What do you think about this kid?”

Hornsby replied, “Well I’ve seen him on television and he misses too many balls.” He told Lopata, “you should get a piece of the ball every time you swing the bat – not necessarily a base hit but get a piece of it.”1

Lopata was smart enough to heed the advice of Hornsby and try to figure out how to see the ball better. As a result, he opened up his stance and began to go into a crouch when he hit. He got two hits that day and then got even lower until it seemed he was almost sitting on top of the batter’s box. The crouch helped him pick up the ball better, cut down on his strikeouts, and generate more power pulling the ball.2 According to Dizzy Dean, by then a famous broadcaster, “He looks like a man hittin’ from an easy chair.”3

Lopata was the first catcher in the National League to wear eyeglasses and had trouble picking up the ball because of the glare from the lights of the Connie Mack Stadium scoreboard. So he started using tinted glasses.4 It certainly seemed to help, because he finished 1954 with a .290 average, the highest of his career, 14 home runs, and 42 RBIs in only 259 at-bats.

Stanley Edward Lopata was born in Delray, Michigan, a neighborhood in Detroit, on September 12, 1925, to Anthony and Agnes Lopata. Anthony was a foundry worker. Both parents were born in Poland and came to the United States in 1911. Stanley was the youngest of five children and had two older sisters, Wanda and Bertha, and two brothers, Casimir and Chester. Stanley grew up in Delray, playing first softball5 and then sandlot baseball. He was a star player at Southwestern High School in basketball and baseball although he played high-school baseball only one year, preferring to develop in American Legion baseball.6 There he played on the same team as future Phillies teammate Bob Miller.7

The hometown Tigers paid Lopata’s bus fare during his summer vacation so that he could catch batting practice at Briggs Stadium. When the game started, Lopata would take the bus home.8 Detroit scout Wish Egan tried to sign Lopata after he graduated from high school in 1943 for a $500 bonus, but on the advice of his American Legion coach, who told him he would be offered more money than that, he turned the offer down.9 He had also worked out for the Washington Senators in Washington and the Brooklyn Dodgers when they were playing on the road in Pittsburgh, but did not sign.10

With World War II at full tilt, Lopata went into the Army in December 1943. He served in the 14th Armored Division as it fought across Europe. He saw heavy action and was awarded the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart before his discharge in late 1945.11 Back home in Detroit, Lopata played in a couple of games with a semipro team in the Detroit Federation and was soon signed by Phillies scout Eddie Krajnik for a hefty bonus of $15,000.12 Krajnik termed Lopata a “can’t-miss” prospect.13

Lopata later related that he signed with the Phillies because, except for Andy Seminick, they did not have too many top catchers in their organization and his hometown Tigers had just paid a large bonus to Frank House, who was also a catcher.14

With a good portion of his bonus, Lopata paid off his parents’ mortgage and bought them some furniture, a refrigerator, and a television. Lopata later said that his dad, a Polish immigrant, had never had any interest in baseball but became very excited about his son’s career after he signed.15

The Phillies sent Lopata to Terre Haute, Indiana, in the Class-B Three-I League, in 1946. He broke into professional baseball with a bang, smashing three home runs, three triples, and two doubles in his first three games.16 He batted .292 at Terre Haute with 9 home runs, and 45 RBIs in 67 games. Also notable for a 6-foot-2, 210-pound catcher, he hit 11 triples. In 1947 he moved up the ladder, to the Utica (New York) Blue Sox, of the Class-A Eastern League. The Blue Sox were the Phillies’ top farm club and under manager Eddie Sawyer the team was loaded with prospects, including future 1950 Phillies Whiz Kids teammates Richie Ashburn, Granny Hamner, and Putsy Caballero. The Blue Sox swept to the Eastern League championship by 10 games with a 90-48 record and then prevailed in the playoffs over Wilkes-Barre and Albany.17 In 115 games, Lopata batted .325, with 9 homers, 20 doubles, and 88 runs batted in. His penchant for triples continued, as he legged out 13 three-base hits. For his stellar season he was named the league’s Most Valuable Player.18

After the season Lopata married Betty Kulczyk on October 25, 1947. He had met Betty, who lived in the next block in Detroit, when he returned from the war.19 And he continued to move up the minor-league chain in 1948, playing for the Toronto Maple Leafs in the Triple-A International League, the Phillies’ new top farm club. In 110 games, he batted .279, with 15 home runs, 20 doubles, 8 more triples, and 67 runs batted in. Eight of his RBIs came in one game. On May 20 against Jersey City he slugged two home runs and drove in eight runs to set a Roosevelt Stadium record.20

On September 19, after the International League season, Lopata was called up to the Phillies. He had just turned 23 a week earlier. On his first day with the team he caught the veteran Schoolboy Rowe in the second game of a doubleheader against the Pittsburgh Pirates. He struck out in his first at-bat against Kirby Higbe and went 0-for-4, but the Phillies won 5-3.

Lopata also caught the second game of a doubleheader against the Pirates the next day. In the sixth inning in a 1-1 game he notched his first big-league hit, a double to left off Tiny Bonham in the middle of a six-run Phillies rally. The knock also drove in his first run and he then scored his first run on a single by pitcher Lou Possehl as the Phillies went on to win 7-4. In all, Lopata appeared in six games, two as a pinch-hitter, and had two hits in 15 at-bats.

Although the Phillies had five catchers in spring training in 1949, Lopata impressed and began the season as the starting catcher21 before eventually splitting time with the veteran Andy Seminick. In a solid rookie campaign, he appeared in 83 games and batted .271 in 240 at-bats with 8 home runs and 27 RBIs as the improving Phillies finished in third place with an 81-73 record.

The team, now dubbed the Whiz Kids because of their youth, continued to improve in 1950, although Lopata played sparingly as Seminick had a career year behind the plate. By late September the team had built a 7½-game lead over the Boston Braves and a nine-game lead over the Brooklyn Dodgers. Then the Dodgers went on a spree, winning 13 of 17 games, while the Phils faltered. During the last week of the season the Phillies lost five straight games while the Dodgers won three straight to close the gap to a single game. The teams faced each other at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field on the last day of the season with the pennant in the balance. If Philadelphia lost, a best-of-three playoff would determine which team would advance to the World Series.

Robin Roberts was on the mound for the Phillies against Don Newcombe of the Dodgers. Lopata did not start the game but replaced Andy Seminick in the ninth inning of a 1-1 tie after Seminick was taken out for a pinch-runner in the top half of the inning. The Dodgers threatened to score and end the game but with no outs outfielder Richie Ashburn made an on-the-money throw to Lopata, who tagged out Cal Abrams 15 feet up the line from home plate in the most famous throw and catch in Phillies history. Roberts retired the next two batters with runners still in scoring position, sending the game into extra innings. The Phillies’ Dick Sisler then hit a dramatic three-run home run in the top of the 10th inning, Robin Roberts shut the Dodgers down in the bottom of the inning, and the Whiz Kids won the Phillies’ first pennant in 35 years.

Of the play that nailed Abrams, Lopata said, “Richie’s throw had Abrams out by 20 to 25 feet. In a way I was surprised they sent him in because they had nobody out and Jackie Robinson, Carl Furillo, and Gil Hodges coming up. It was [a] perfect throw from Richie. There was still only one out, but [Roberts] … reached back and got that little extra. … He reached back and got them out. When Tommy Brown popped up to Eddie Waitkus for the final out in the 10th, we just charged the mound. We were so happy, especially after what we went through the final week of the season.”22

The World Series saw the Phils’ bats go quiet as they were swept by the New York Yankees in four games, three of which were decided by one run. Lopata caught one inning in Game Two and struck out on a high fastball as a pinch-hitter in Game Four – the last out of the Series – facing Allie Reynolds in relief of Whitey Ford. For the season Lopata had appeared in 58 games and hit only .209 in 129 at-bats.

Lopata continued to struggle in 1951. He had trouble making contact with the ball coming out of spring training and played in only three games with the Phillies before being sent to the Baltimore Orioles in the International League. There he hit only .196 in 38 games. In 1952 Lopata improved enough to make the Phillies as a backup to catcher Smoky Burgess after Seminick was traded to Cincinnati. He batted a solid .274 in 57 games. He increased his playing time to 81 games in 1953, but his batting average fell to.239 in 234 at-bats.

Despite his problems at bat, the Phillies valued Lopata for his prowess on defense. His strong arm enabled him to cut down many runners at second base. He also was a bulwark at the plate against players trying to score. On one occasion Enos Slaughter came barreling around third base intent on scoring. Lopata got the ball at about the same time Slaughter arrived at the plate. Slaughter rammed into Lopata and bounced back close to six feet, called out by the umpire with an assist from Stan’s stature.

Lopata later said, “I was no slouch at blocking home plate. I figured that was one of the greatest plays in baseball, blocking home plate. As big as I was, with the shin guards and chest protector, if anyone wanted to run into me and try to knock me over, go ahead, they were welcome to it. I really loved that play and I sure loved blocking home plate.”23

Lopata was also an excellent baserunner and had outstanding speed, as all the triples he hit in the minor league would suggest. Although he stole just 18 bases in his career, he was the fastest man on the Phillies next to Richie Ashburn before his knee injury24

It was in 1954 that Lopata heeded the advice of Rogers Hornsby to try to see the ball better and adopted the crouch as his stance. It worked. In 86 games he batted .290, hit 14 home runs, and had 42 runs batted in. He would uncoil from his crouch as the pitcher delivered the ball. He was seeing the ball better and offered a tougher target for the pitchers. Though he was improving at the plate, he was still a backup catcher to Smoky Burgess, who had a terrific year with the Phils, batting .368 in 108 games.

In 1955 Lopata shared the catching with Andy Seminick, who was back with the Phillies after an early-season trade. He continued to show more pop and at the All-Star break was hitting .251 with 9 home runs. National League All-Star manager Leo Durocher had not selected Richie Ashburn, who was batting .327 to lead the league in hitting, allegedly because of his lack of power. But when Roy Campanella was injured and unable to play, Durocher added Lopata to the team.25 He entered the game in the seventh inning as a pinch-hitter for Smoky Burgess. He grounded to Chico Carrasquel at shortstop but was safe when Carrasquel booted the ball to allow Hank Aaron to score an unearned run. Lopata played the remainder of the game and went hitless in three trips to the plate as the National League won, 6-5, on Stan Musial’s 12th-inning home run.26

On September 4, Lopata survived a scare by collapsing twice in a game against the New York Giants, once in the dugout after hitting a three-run home run off Ruben Gomez and then again in the clubhouse. He was taken to Temple University Hospital, where he was thought to be suffering from a delayed reaction to being beaned a few days earlier.27 He was able to return to action by September 8.

For the 1955 season Lopata batted .271 in 99 games. He hit 22 home runs, a career high thus far, in 303 at-bats and drove in 58 runs. His bat was strong enough that manager Mayo Smith played Lopata at first base in 24 games instead of regular first baseman Marv Blaylock, who struggled against left-handed pitching.

Lopata became the Phillies’ regular catcher in 1956 and had a banner year. He exhibited prodigious power, smashing a spring-training home run in Clearwater against the Reds 510 feet over the center-field wall. On July 31 against Sam Jones of the Cubs, he blasted a shot 452 feet over the double-decked left-field pavilion in Connie Mack Stadium. According to teammate Robin Roberts, Lopata had “muscles on the muscles that are on his muscles.”28 He also continued to spell Blaylock at first, appearing in 39 games there. He again made the All-Star team as an injury replacement, this time for Del Crandall, but did not see action in the game.29 In 146 games that year, he batted .267, slugged 32 home runs, and had 95 runs batted in. He had a slugging percentage of .535 and 286 total bases, scored 96 runs, and hit 33 doubles. His 32 homers set a record, since broken, for Phillies right-handed batters.

The Phillies finished in fifth place with a disappointing 71-83 record. After the season management stated that everyone on the roster could be traded except for Lopata.30

As good as Lopata’s 1956 season was, 1957 was more of a struggle. He suffered a variety of injuries that cut down on his effectiveness at bat and behind the plate. It started in spring training, where he suffered an injury to his right hand from a foul tip. In May he pulled a muscle in his leg. In June he injured his throwing shoulder. The worst injury occurred on July 11, when he twisted a knee in a rundown between third and home. He returned with a bang, slamming two home runs on July 21 in a loss to Cincinnati. He then hit home runs in four consecutive games from July 30 through August 2.

Lopata earned a lot of respect as he played through his knee injury. He’s a team man,” said Phillies manager Mayo Smith. “He wants to play even though he knows that as long as he does the knee will probably bother him all season long.” Phillies trainer Frank Wiechec agreed, “He’s a real courageous guy in my book,” said Wiechec. “For a while the pain in his knee was so severe that he couldn’t sleep at night. His insistence on playing contributed to other things. Favoring his right knee, his left leg became sore, his hips got out of line and his back got tight, but he spends hours with me before and after every game and he’d even catch doubleheaders if Smith asked him to.”31 With all the injuries, not surprisingly Lopata struggled at the plate and wound up hitting .237 in 116 games with 18 home runs and 67 RBIs.

During the offseason Lopata had knee surgery at Temple University Hospital in Philadelphia. After the surgery he spent five days a week at Connie Mack Stadium rehabbing the knee. He got off to a very slow start, however, in 1958 and by early May was hearing the boo birds at home. He then began showing some of his old power and hit five home runs that month, but on June 8 in the first game of a doubleheader he was beaned on a pitch from the Cardinals’ Larry Jackson. Although it was reported not to be serious, he was not released from the hospital until June 11.32 He recovered from the beaning but battled more injuries in July and hit only three more homers the rest of the year while splitting the catching duties with Carl Sawatski. For the season, Lopata batted .248 in 86 games and 258 at-bats with 9 home runs and 33 runs batted in.

Lopata agreed to a pay cut for 1959 and went to spring training with the club. But the Phillies had finished in the cellar in 1958 and were looking to bring in new blood, so on March 31, Lopata was traded to the defending National League champion Milwaukee Braves, along with infielder Ted Kazanski and utilityman Eddie O’Brien, for pitcher Gene Conley, infielder Joe Koppe, and outfielder Harry Hanebrink. Lopata was initially very enthusiastic about the trade, saying that his knee was strong and that he was looking forward to playing in front of “friendly crowds.”33 However, once the season started he played sparingly behind regular catcher Del Crandall and didn’t record his first hit of the season until mid-July. For the season, Lopata appeared in only 25 games and batted a paltry .104.

The Braves released Lopata in October34 but then brought him to 1960 spring training, where manager Charlie Dressen announced that he intended to get Lopata into more games as the backup to Crandall.35 It did not work out, however, as Lopata appeared in only seven games before the Braves, optioned him to Louisville in the American Association in late June.36 With the Colonels he hit .246 with 12 home runs and 28 runs batted in in 55 games. The Braves recalled him in briefly in September but he did not appear in any games and was soon returned to Louisville. In his final professional game, Lopata helped the Colonels defeat the Toronto Maple Leafs of the International League by a 5-1 score to wrap up the Little World Series crown for Louisville.37

The Braves gave Lopata his unconditional release on October 14, 1960, and at 34, Lopata retired from baseball.

In 13 major-league seasons (853 games) Big Stash batted .254, belted 116 homers, drove in 397 runs, scored 375 runs, and had 116 doubles and 25 triples. In 695 games behind the plate, he had a .986 fielding average.

After retiring from baseball, Lopata worked for a time in a steel plant in Dearborn, Michigan. He then moved to Abington, Pennsylvania, in the Philadelphia area and worked as a salesman for IBM, which at the time made tabulating cards and tapes for computers. Philadelphia Eagles great Chuck Bednarik got him into the Redi-Mix concrete business, where he rose to become the vice president of sales for JDM Materials. He held that position for 19 years, overseeing sales from 11 plants in eastern Pennsylvania.

Lopata underwent quadruple bypass surgery in Philadelphia in 1985. He retired from the concrete business, and he and his wife, Betty, moved to Mesa, Arizona, in 1986.38 They had seven children, 16 grandchildren, and eight great-grandchildren. Lopata took up golf and wood carving, especially making Kachina dolls. He was inducted into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame in 1988 and the National Polish-American Hall of Fame in 1997.

Lopata died of a heart ailment on June 15, 2013, at the University of Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia. He was 87 years old.39

Despite the injuries that hampered his baseball career, Lopata was not at all bitter. He said, “The Lord gave me the ability to play baseball, I tried to make use of everything he gave me. Hard work and hustle helped me – mostly hard work. And after I changed my batting stance, I was a good-hitting catcher there for a while.” 40

Sources

In addition to the sources listed in the Notes, the author also consulted the following:

BaseballLibrary.com.

Lieb, Frederick G. and Stan Baumgartner. The Philadelphia Phillies (New York: G.P Putnam’s Sons, 1953, reprinted by Kent State University Press, 2009).

Orodenker, Richard, ed. The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Paxton, Harry T. The Whiz Kids – the Story of the Fightin’ Phillies (New York: David McKay Company, Inc., 1950).

Roberts, Robin, and C. Paul Rogers III. My Life in Baseball (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003), reprinted as Throwing Hard Easy – Reflections of a Life in Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014).

Van Lindt, Carson. Fire and Ice – The Story of the 1950 Phillies (New York: Marabou Publishing 1998).

Westcott, Rich. A Century of Philadelphia Sports (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

Westcott, Rich, and Frank Bilovsky. The New Phillies Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993).

Notes

1 Interview with author, September, 10, 1993; Baseball-almanac.com/players/player.php?p=lopatst01.

2 Skip Clayton and Jeff Moeller, 50 Phabulous Phillies (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, Inc., 2000), 116. After adopting his crouch, Lopata became a dead pull hitter, and said he couldn’t hit the ball on the right side of the field if he tried. The Brooklyn Dodgers eventually adopted a shift and moved the second baseman over to the left of second base. Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

3 Edgar Williams, “Sit Down Hitter,” Baseball Digest, November-December 1956: 75.

4 Williams: 78.

5 When Lopata was 6 or 7, the neighborhood kids had only one softball and Lopata became “the official sewer” to stich the cover back on when it came off because he had access to a needle and string. “Mirrors of Time – Reflections From the Past,” One More Inning – A Baseball Journal, September, 1993 (copy on file with the author).

6 Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

7 The Detroit sandlots and American Legion program produced a large number of major leaguers during this time. In addition to Lopata and Miller, catchers Hobie Landrith, Harry Chiti, and Joe Ginsberg, and pitcher Al Houtteman came from the Detroit sandlots. Earlier, the Detroit sandlots produced Barney McCosky, Ted Gray, and Hal Newhouser. Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

8 Those Tigers had Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, Billy Rogell, and Mickey Cochrane (who was Lopata’s boyhood hero) as well as pitchers Schoolboy Rowe and Elden Auker. Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 170.

9 Roberts and Rogers, 171.

10 “Mirrors of Time”; Interview with author, September 10, 1993. After the end of the war he remained in Germany for a few months and was able to play service basketball. Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

11 “Mirrors of Time.”

12Roberts and Rogers, 171. Other sources have Lopata’s bonus at $20,000. John F. Morrison,“Stan Lopata, 87, Legendary Phillies Catcher of the 1950s,” Philadelphia Daily News June 21, 2013. Krajnik saw Lopata work out one time in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium and signed him quickly afterward. “Phil Scout ‘Stole’ Lopata From Tigers’ Kid School,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1949: 6.

13 Unidentified and undated clipping in the Stan Lopata clippings file, National Baseball Library.

14 Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

15 Roberts and Rogers, 171; “Mirrors of Time.”

16 “Phil Scout ‘Stole’ Lopata From Tigers’ Kid School.”

17 Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, eds., The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham: Baseball America, Inc., 2nd. ed., 1997), 358.

18 Stan Baumgartner, “All-Star Team Coming up to Blue Jays from Utica Farm – But Not Next Year,” The Sporting News, November 26, 1947: 17.

19 Williams, 80.

20 Associated Press, “Leafs Trim Jersey City,” Ottawa Citizen, May 21, 1948: 21.

21 J.G.Taylor Spink, “Lopata Comes Long Way After Slow Start,” The Sporting News, April 27, 1949: 6.

22Roberts and Rogers, 316-17.

23 Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

24 Williams, 76. Lopata recalled that in spring training one year the team raced in a series of 50-yard dashes and the only teammate who beat him was Ashburn. Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

25 Unidentified clipping dated July 8, 1955, in the Stan Lopata clippings file, National Baseball Library.

26 David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of the All-Star Game (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2001), 139-43.

27 “Catcher Lopata Is Hospitalized After Collapse, Montreal Gazette, September 5, 1955: 18.

28 Williams, 76.

29 Unidentified clipping dated July 7, 1956, in the Stan Lopata clippings file, National Baseball Library; Vincent et al., 146, 149. Lopata later recalled that after the game National League manager Walter Alston apologized for not getting him into the game. Interview with author, September 10, 1993.

30 “Phillies Trade Ennis for Repulski,” Chicago Tribune, November 21, 1956: 5.

31 Allen Lewis, “Lame Lopata Still Phillies’ Best Stepper,” unidentified clipping dated August 14, 1957, in the Stan Lopata clippings file, National Baseball Library.

32 Associated Press, “Stan Lopata Gets Hospital Release,” Baltimore Sun, June 12, 1958: S20.

33 Red Thisted, “Shot With Champs Best Things – Lopata,” Milwaukee Sentinel, April 2, 1959: 2.4. Lopata later said that he was a little surprised and a little disappointed by the trade but was happy to still be in the big leagues. Clayton, 117.

34 Unidentified clipping dated October 17, 1959 in the Stan Lopata clippings file, National Baseball Library.

35 Bob Wolf, “Dressen Designates Lopata as Second String to Crandall,” Milwaukee Journal, February 11, 1960: 2.13.

36 Bob Wolf, “Lopata to Minors,” Milwaukee Journal, June 25, 1960: 12.

37 “Louisville Wins, 5-1, Takes Little Series,” Milwaukee Journal, October 3, 1960: 2.17.

38 “Mirrors of Time.”

39 Morrison.

40 Baseball-almanac.com\players\player.php?p=lopatst01.

Full Name

Stanley Edward Lopata

Born

September 12, 1925 at Delray, MI (USA)

Died

June 15, 2013 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.