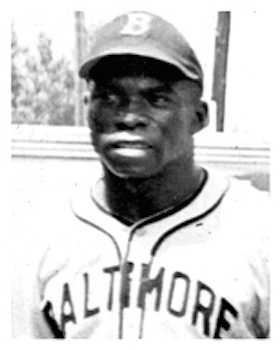

Henry Kimbro

Henry Kimbro was a stocky speedster who earned his living slap-hitting baseballs between third base and shortstop or into the outfield gaps. He served as the leadoff hitter for the Baltimore Elite Giants for 13 of his 18 seasons in the Negro Leagues. Kimbro was not known for power, but his 5-foot-8 and 175- pound frame could generate quite a punch when he chose. He is one of the few players ever to launch a home run over the roof of Briggs Stadium in Detroit. A fine defensive outfielder, he started in five East-West Games from 1941 to 1947 and was a late substitute in another. He added three more all-star appearances in the 1950s, although the Negro Leagues were losing their luster by then.

Henry Kimbro was a stocky speedster who earned his living slap-hitting baseballs between third base and shortstop or into the outfield gaps. He served as the leadoff hitter for the Baltimore Elite Giants for 13 of his 18 seasons in the Negro Leagues. Kimbro was not known for power, but his 5-foot-8 and 175- pound frame could generate quite a punch when he chose. He is one of the few players ever to launch a home run over the roof of Briggs Stadium in Detroit. A fine defensive outfielder, he started in five East-West Games from 1941 to 1947 and was a late substitute in another. He added three more all-star appearances in the 1950s, although the Negro Leagues were losing their luster by then.

Henry Allen Kimbro was born on February 10, 1912, in Nashville, Tennessee. He was the fifth child born to Will and Sallie (King) Kimbro. Both were Tennessee natives and resided in West Nashville. Will is listed as a cemetery groundskeeper in census reports and also raised crops for Walden College.1 Sallie tended the children and took in laundry when the need arose. Kimbro attended school near home through the sixth grade, but the Black junior high was a 10- to 12-mile trek to the other side of town and that discouraged him from further schooling.

Kimbro took a job at a gas station where he worked into his early twenties. There he learned how to repair cars, keep them running, and even give them extra power. He earned a reputation as a top-notch driver and was rumored to have run moonshine in Western Tennessee. During his baseball career, his knowledge of cars came in handy as he helped to repair the team buses (Chevrolet and Buick) and served as a backup driver.

Kimbro met and fell in love with Nellie Bridges. They married and a son, Larry, was born March 10, 1936. That April, Kimbro departed home for the baseball season, leaving Nellie alone with Larry for over five months. The marriage was a struggle and the long separations made life even more difficult. Their volatile marriage eventually ended in divorce. In the mid-1940’s, Kimbro had a relationship with a woman in Baltimore that produced a daughter, Geraldine. Kimbro included her as best he could in his life, but the family eventually lost track of her. She was his only child that did not complete college.

Tom Wilson had been sponsoring teams in Nashville for more than a decade when he became aware of Kimbro’s talents on the amateur diamonds. He approached the speedster about joining the Nashville Elite Giants, but Kimbro turned him down at first. Then, in the fall of 1935, Kimbro joined a barnstorming troupe on a southern swing. He must have enjoyed the pay-for-play lifestyle because he signed with Wilson’s Elite Giants in 1936 and went with the team when it transferred to Columbus, Ohio. In 1937 the franchise shifted to Washington, D.C., and joined the Negro National League. That fall, Kimbro joined a group of all-stars managed by Oscar Charleston. The highlight of the squad’s short tour was playing Satchel Paige’s team before 35,000 fans at Yankee Stadium.

In 1938 the Elite Giants made Baltimore their home and installed Kimbro as the leadoff hitter and center fielder. Nicknames were very common in baseball, and Kimbro was frequently called “Jimbo” or “Kimmie.” In 1939 the Elite Giants barely earned a spot in the playoffs. They beat Newark in the first round of the NNL2 playoffs and then defeated the Homestead Grays in the league’s championship series. Kimbro batted .235 (8 for 34) in nine playoff games, but he had hit .319 in league games to help get them to the playoffs. His defense earned raves, especially in Game Two when he made two spectacular catches. One came in the third inning when “he raced from deep centerfield to haul in Vic Harris’ terrific clout near the right-field fence.”2

Kimbro made his first trip to Cuba that fall with a group sponsored by Grays owner Cum Posey. They won all six games in the series. Kimbro remained in Cuba after the series and played for the winter-league champion Almendares ballclub.

After the Homestead Grays earned the Negro National League title in 1940, Wilson decided the Elite Giants needed a shake-up. In April 1941 he put together a two-part swap with the New York Black Yankees. When all the wheeling and dealing was done, the Black Yankees had Kimbro, three pitchers, two catchers, first baseman Red Moore and cash. Baltimore added first baseman Johnny Washington, center fielder Charlie Biot, plus a pitcher and a catcher.3

New York manager Tex Burnett tried to get Kimbro to drop his slap-hitting style and go for the long ball. He even installed Kimbro in the third spot of the lineup. The experiment did not last long. Kimbro had a .300 average for the season, but failed to hit a single home run. He was back in the leadoff position by late June. Kimbro was named a second-team outfielder on the Pittsburgh Courier’s “Dream Team for ’41.” The team was selected by Cum Posey and included players from the American and National Negro Leagues as well as the Mexican League.4

In February 1942, Wilson made another deal with New York, this time returning Kimbro to Baltimore for Biot and pitcher Schoolboy Griffith. The Giants and Grays staged a hard-fought pennant chase. On August 9, Giants catcher Roy Campanella and infielder Sammy Hughes chose to play in an exhibition game against a White all-star team and missed a crucial game with the Grays. Unsurprisingly, the players were suspended. Campanella responded by going to Mexico for the remainder of the season, and Baltimore finished just behind Homestead in the second-half pennant race. That winter, as he had in 1941, Kimbro went with the Elite Giants to the California Winter League. The next couple of winters he stayed in Baltimore and worked on defense jobs.

The Elite Giants fell to fifth place in 1943 and struggled to a second-place finish in 1944. Kimbro’s game kept improving, and his average was well over .300 in 1944. He duplicated his strong stats in 1945 and 1946 but the team never reached the championship. In the winter of 1946, he played for Havana. There he met Erbia de la Candida Del Rosario Mendoza, who was a student at a Havana teacher’s college. Neither spoke the other’s language, but, with friends and family acting as translators, they fell in love. Kimbro followed the traditional Cuban rules on courtship. The couple was able to date only if escorted by chaperones. Often, they simply sat together in the family home. He wooed the family with trips to the movies and chocolate.5 After the 1947 season he returned to Cuba and won the batting title with a .346 average. It was initially reported that he earned a $1000 bonus for his efforts, but that was lowered to $600 in later reports.6 In addition to the title, Kimbro set an all-time Cuban winter mark with 104 base hits, was named an all-star, and anchored Havana’s championship team.7

Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby broke the major-league color barrier in 1947, but Kimbro got very little attention as a potential big-leaguer. He had a reputation as a loner, his age (35) was working against him, and, by his own admission, “if somebody did something to me, I’d have been up at ‘em. No way in the world I wouldn’t have fought back.”8 When spring training opened in 1948, manager Candy Jim Taylor was hospitalized in Chicago and Kimbro was put in charge. When Taylor passed away, Jesse “Hoss” Walker was hired as manager. The Elite Giants won the first half pennant in 1948 but dropped the playoff series to the Grays in three straight games.

That winter, Kimbro returned to Cuba, where he led the league in walks. Patience at the plate was an integral part of his game. Teammate Butch McCord claimed. “I never saw him swing at a first pitch.” After that season, Kimbro returned to the island to continue the courtship of Erbia, but he did not play baseball. Their daughter, Harriet, thinks he made only one trip a year until he finally earned permission to wed Erbia. He brought his fiancée back to Nashville where they were married on September 5, 1952.9 Over the course of their marriage, the couple welcomed two daughters and a son and enjoyed their lives together in Nashville; the children remember taking trips back to Cuba in the 1950s.

In 1949 the Elite Giants ran the table and defeated the Chicago American Giants to win the Negro American League championship, 4-0. In September, the Afro-American credited Kimbro with a .332 average; the Howe News Bureau credited Kimbro with a final season batting average of .360, but this figure likely also included his performances in exhibition games.10 The Negro Leagues were winding down, but the 1950 Elite Giants were still going strong. Kimbro, now 38, was still a force at leadoff and in the field. On July 17, he added the title of manager to his resume when skipper Lennie Pearson was sold to Milwaukee of the American Association. The Giants won his first game, 5-4, over the Birmingham Black Barons but finished behind the New York Cubans and missed the playoffs. When the Elite Giants disbanded after the 1951 season, Kimbro moved to the Birmingham Black Barons and played for the team through 1953. By that time, the Negro Leagues had shrunk to four teams and Kimbro was 41 years old. He retired from baseball and took up family life as well as an arduous seven-days-a-week work schedule.

After a few years as a cab driver, Kimbro purchased a gas station and eventually started Bill’s Cab Company in Nashville. Both endeavors proved to be successful and provided the family with steady income for over two decades. Kimbro was able to afford college for Larry (Tennessee State), Harriet (Fisk), Philip (Fisk), and Maria (Florida A&M). More importantly, “Daddy taught us how to live, how to triumph over any odds, how to succeed,” his daughter Harriet later told the Tennessean.11 After retirement Kimbro often met with fellow Negro Leaguers at a Nashville sports shop called the “Old Negro League Sports Shop.” The “loner” image from his early days was a thing of the past.

When the National and American leagues chose to honor the Negro Leagues at events during the 1990s, Kimbro was a frequent invitee, including an appearance at the 1993 All-Star Game at Camden Yards. He was inducted posthumously into the Tennessee Sports Hall of Fame in 2003.

In his final years he struggled with a heart condition. After repeated hospitalizations in 1999, he opted to return home rather than to try experimental surgery. He died at his Nashville home on July 11, 1999, of congestive heart failure. After funeral services at the Patterson Memorial United Methodist Church, he was laid to rest in Greenwood Cemetery not far from where he grew up.

Sources

All Negro League statistics and team records were taken from the Seamheads.com Negro League Database, unless otherwise indicated.

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted a number of other publications including:

Clark, Dick & Larry Lester. eds. The Negro Leagues Book (Cleveland, Ohio: SABR, 1994).

Heaphy, Leslie A. The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2003).

Kelley, Brent. Voices from the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 1998).

Luke, Bob. The Baltimore Elite Giants (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

Notes

1 Harriet Kimbro-Hamilton, “Daddy’s Notebook” (Huntsville, Alabama: In Due Season Publishing: 2015); 15-16.

2 “Baltimore Bats Way to Titular Battle with Grays.” Pittsburgh Courier, September 23, 1939: 16.

3 Hayward Jackson, “Elites get Johnny Washington in Big Swap with Yankees,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 12, 1941: 16.

4 Cum Posey, “Posey’s 18th All American Baseball Team,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 25, 1941: 16.

5 Tasneem Ansariyah-Grace, “In a League of his Own,” Tennessean (Nashville), March 4, 2000: 30. Also, information from Harriet Kimbro-Hamilton in email exchanges in May 2016.

6 Afro-American (Baltimore), March 20, 1948 and April 17, 1948.

7 Jorge S. Figueredo, Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History, 1878-1961 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2007).

8 Randy Horvick, “They Might Have Been Heroes,” www.nashvillescene.com, May 2, 1996.

9 Kimbro’s Hall of Fame questionnaire lists it as 1951. His daughter’s book and various newspaper sources use the 1952 date.

10 “Negro American League (1949) League Leaders,” Center for Negro League Baseball Research, http://www.cnlbr.org/Portals/0/Stats/NAL%201949/NAL1949.pdf, accessed January 29, 2023.

11 Harriet Kimbro-Hamilton, Tennessean, March 4, 2000: 30.

Full Name

Henry Allen Kimbro

Born

February 10, 1912 at Nashville, TN (US)

Died

July 11, 1999 at Nashville, TN (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.