October 1892: The Split-Season Playoff

Major-league baseball faced a serious crisis in the early 1890s. Players rebelling against the reserve clause had created the independent Players’ League to challenge the existing National League and the American Association in 1890. The ensuing season, in which three major leagues competed for fans and revenues, weakened baseball overall. The Players’ League folded after a single season, the American Association neared insolvency in late 1891, and even the venerable National League languished.

Major-league baseball faced a serious crisis in the early 1890s. Players rebelling against the reserve clause had created the independent Players’ League to challenge the existing National League and the American Association in 1890. The ensuing season, in which three major leagues competed for fans and revenues, weakened baseball overall. The Players’ League folded after a single season, the American Association neared insolvency in late 1891, and even the venerable National League languished.

National League and American Association representatives found a solution when they met in Indianapolis in December 1891 and agreed to consolidate the two leagues. The new organization combined the eight National League teams with four American Association franchises to create what Sporting Life editor Francis Richter called the “big league.” In order to accommodate more teams, league directors decided to expand the standard 140-game season to 154 games, and they established a split-season format. Hoping that a different team would win each split-season, the directors tentatively planned a postseason “world championship series.”

The Indianapolis agreement also needed to reconcile significant differences between the two organizations. The new league established a standard 50-cent admission, but allowed the former American Association teams to charge their traditional “two bits” – 25 cents. Likewise, former AA ballparks could sell alcohol (the Association had acquired the nickname Beer and Whiskey League) forbidden at teetotaling National League grounds, and could schedule games on Sunday, violating the long tradition of blue laws in National League cities.1

The 1892 season began on April 12 with more than 40,000 fans turning out. The Boston Beaneaters quickly moved into first place, with the Brooklyn Bridegrooms and the Cleveland Spiders competing for second. When the first half ended on July 13, Boston (52-22) led second-place Brooklyn (51-26) by 2½ games. Sporting Life attributed Boston’s success to pitching, baserunning, and teamwork. The report described Cleveland (40-33), which finished fifth, as “one of the best-balanced teams in the League, being equally strong in batting, fielding and base-running, well-handled and aggressive.”2

When the second half of the season began, on July 15, Boston started slowly while Cleveland, Brooklyn, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati dominated. Cleveland broke away from the pack at the end of the month, remaining solidly in first for the remainder of the season. Although Boston (50-26) made a late-season run, the Spiders (53-23) finished the second half on October 15 with a three-game lead.3 The dual champions enabled a best-of-nine “world’s championship series” to begin, with the teams playing three games each in Cleveland, Boston, and, if necessary, New York.4

Both teams engaged in a bit of trash-talking. When Boston manager Frank Selee complained that late-October weather would lead to postponed games and reduce attendance, Cleveland’s player-manager, Patsy Tebeau, suggested that “the Beaneaters fear the humiliation of possible defeat.”5 Tebeau termed the cold weather a “dodge … simply an excuse to avoid playing Cleveland.”6 Selee responded that “the Boston players are willing to go for broke on their ability to beat the club that has been ‘easy’ for [us] all year.”7

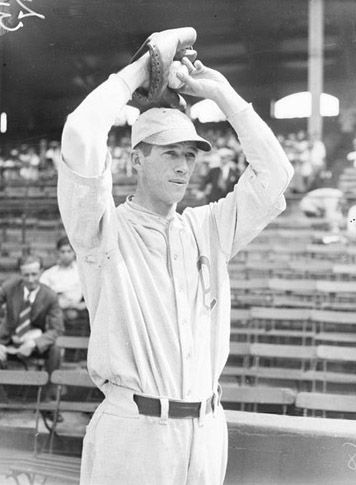

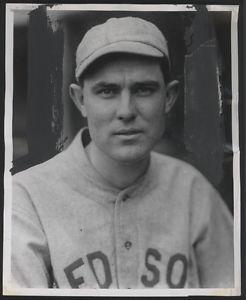

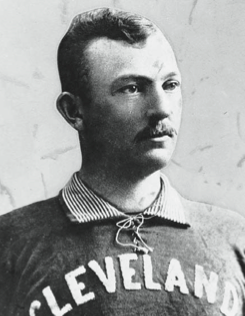

Bettors made the Spiders the early favorite based on their pitching staff. Cy Young had gone 36-12 with a 1.93 earned-run average, while rookie George “Nig” Cuppy had a 28-13 record with a 2.51 ERA. Meanwhile, fans attributed Boston’s second-half decline to the poor performance of aging superstar Mike “King” Kelly. Described as “one of the biggest failures of the base ball season,” Kelly batted only .189, well below his career .308 average.8

The series began in Cleveland on Monday, October 17, as more than 6,000 fans watched the two teams play to a 0-0 tie. Sporting Life described the game succinctly: “It was altogether a pitchers’ battle and not a run had been scored, when, after the eleventh inning, the game was called owing to darkness.”9

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Cleveland |

|

0 |

4 |

1 |

|

Boston |

|

0 |

6 |

0 |

Batteries: Young (CLE) vs. Stivetts (BOS)

Boston, choosing to bat first, edged Cleveland, 4-3, in the second game, on October 18. The Beaneaters’ center fielder, Hugh Duffy, led Boston to victory with a double and two triples, while the Spiders sent “the ball time and again into some fielder’s waiting hands.”10

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Boston |

|

4 |

10 |

2 |

|

Cleveland |

|

3 |

10 |

2 |

Batteries: Staley (BOS) vs. Clarkson (CLE)

Boston won Game Three, 3-2, in an excellent contest whose “agony was not over until the last man was out.”11

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Cleveland |

|

2 |

8 |

0 |

|

Boston |

|

3 |

9 |

2 |

Batteries: Young (CLE) vs. Stivetts (BOS)

The series moved to Boston’s South End Grounds, where the Beaneaters won Game Four, 4-0, on Friday, October 21.

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Cleveland |

|

0 |

7 |

2 |

|

Boston |

|

4 |

6 |

0 |

Batteries: Cuppy (CLE) vs. Nichols (BOS)

The Spiders started strong in Game Five on Saturday, October 22, scoring six runs in the top of the second inning. But Boston came back to win, 12-7.12

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Cleveland |

|

7 |

9 |

4 |

|

Boston |

|

12 |

14 |

3 |

Batteries: Clarkson (CLE) vs. Stivetts (BOS)

Both league rules and state laws required the two teams to take Sunday off before playing Game Six on Monday, October 24. A Cleveland victory would have moved the series to New York for the next game, but Boston won, 8-3.

|

|

|

R |

H |

E |

|

Cleveland |

|

3 |

10 |

4 |

|

Boston |

|

8 |

11 |

5 |

Batteries: Young (CLE) vs. Kid Nichols (BOS)

Sporting Life provided an apt description for the series: “The Clevelands put up a stiff game and fought every inch, but they [played] against a team that has proved their superiors in all the points of the national game.”13 Cranks also ignored manager Selee’s fear of bad weather as more than 32,000 attended the series’ six games.

League directors nonetheless decided to abolish the split-season format and cut the season back to 132 games for 1893. The “big league” itself continued through the 1899 season, when the league dropped four teams. A true World Series would not return until 1903 with the advent of the American League.14

This essay was originally published in Bill Felber, ed., Inventing Baseball: The 100 Greatest Games of the 19th Century (Phoenix: SABR, 2013).

Notes

1 “The Revolution,” Sporting Life, December 19, 1891: 1.

2 “The Record,” Sporting Life, July 16, 1892: 3.

3 “The Season’s End,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 4.

4 “The Big League,” Sporting Life, September 24, 1892: 2.

5 “Tebeau Talks,” Sporting Life, October 8, 1892: 11.

6 Ibid.

7 “20/3,” Sporting Life, October 15, 1892: 3.

8 “Editorial Views, News, Comment,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 2. Both Baseball-reference.com and Retrosheet give King Kelly’s BA as .307, not .308

9 “The World’s Championship Series,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 4.

10 “Boston Wins the Second Game,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 4.

11 “Boston Wins Again,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1892: 4.

12 “The World’s Series,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1892: 3.

13 Ibid.

14 “The Big League,” Sporting Life, October 8, 1892: 2.

Additional Stats

Boston Beaneaters

vs. Cleveland Spiders

Corrections? Additions?

If you can help us improve this game story, contact us.