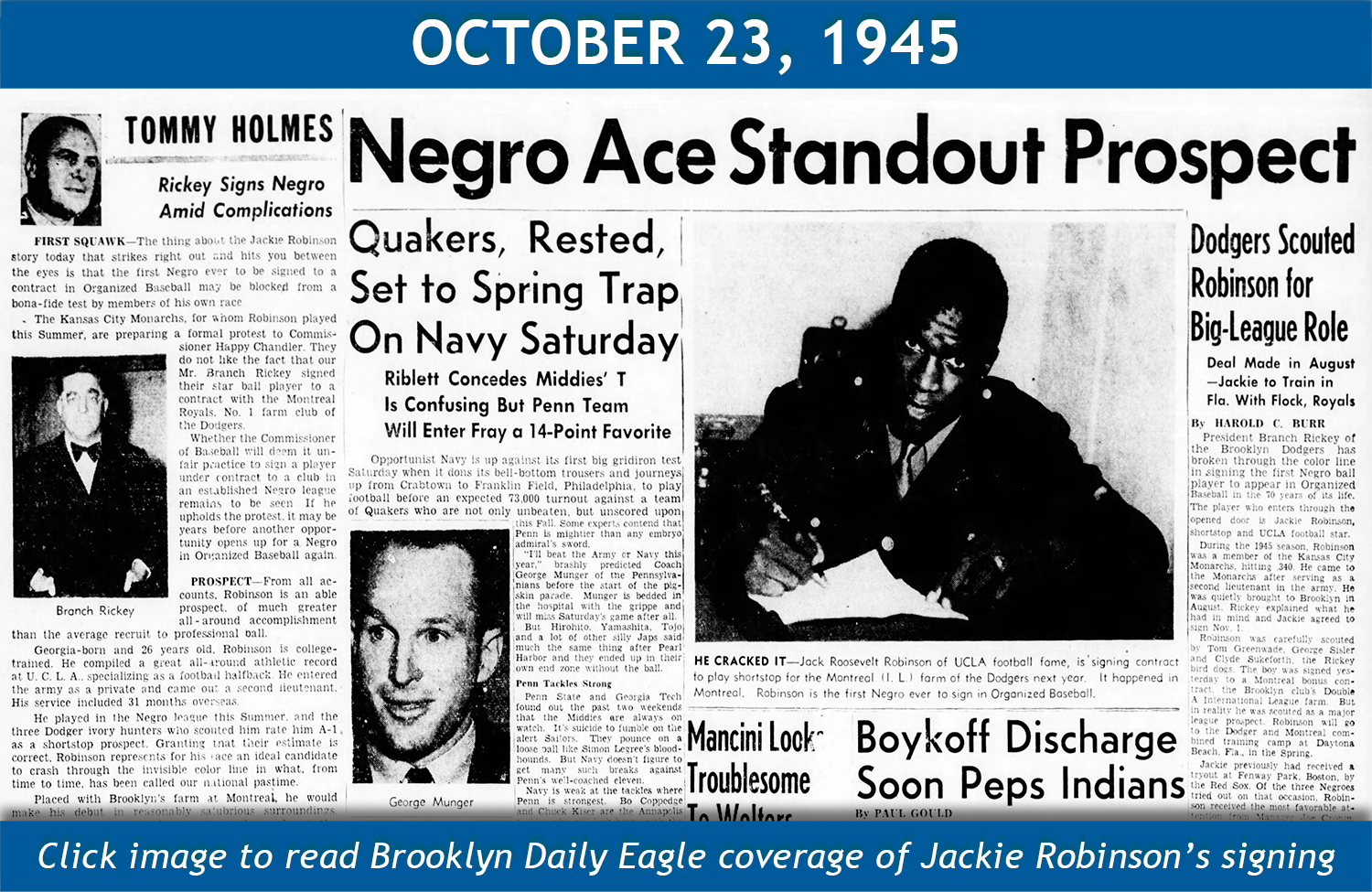

1945: Signing with the Dodgers

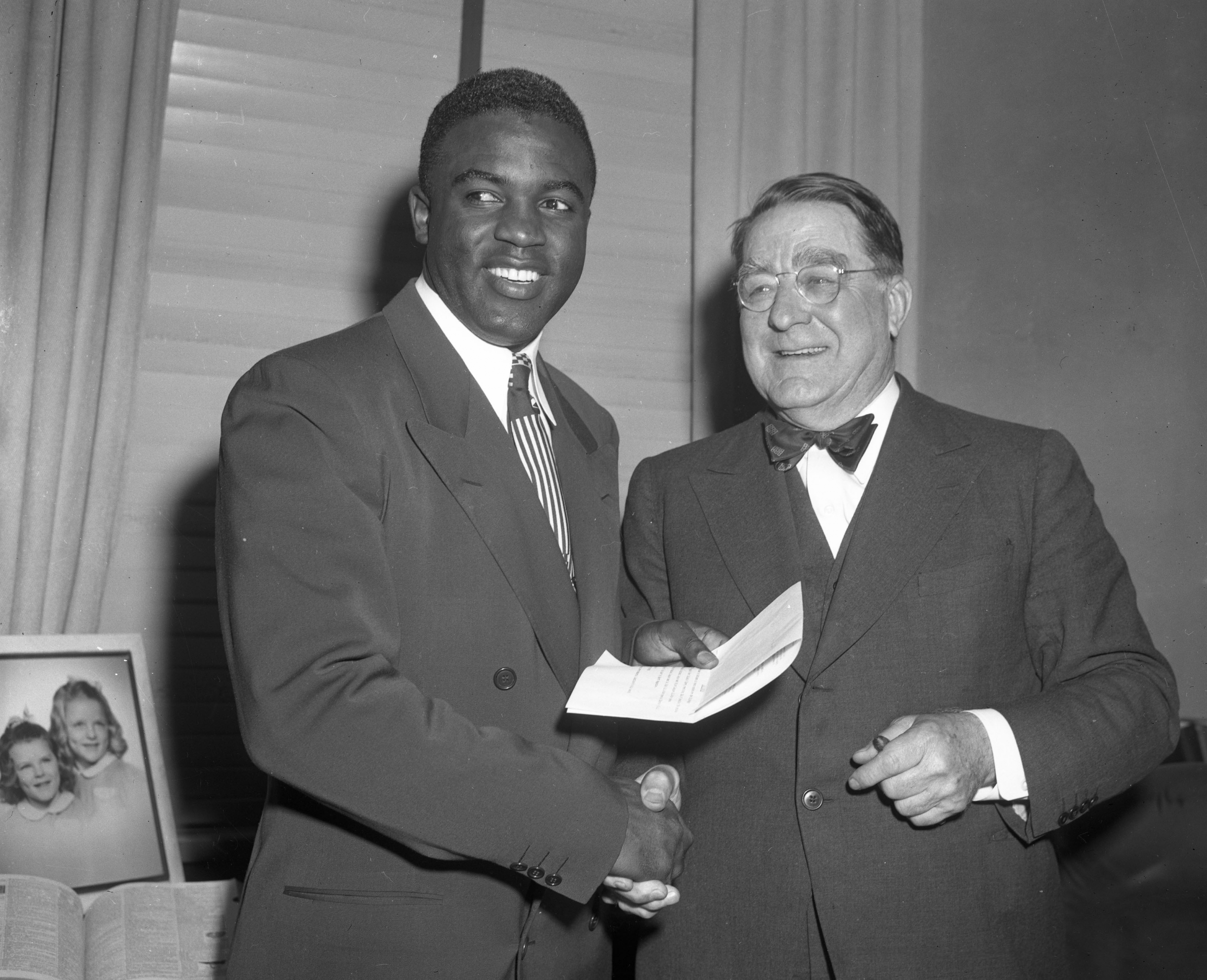

Jackie Robinson and Branch Rickey, seen here in 1950, made history together when Robinson signed a minor-league contract to play for the Montreal Royals of the International League on October 23, 1945. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

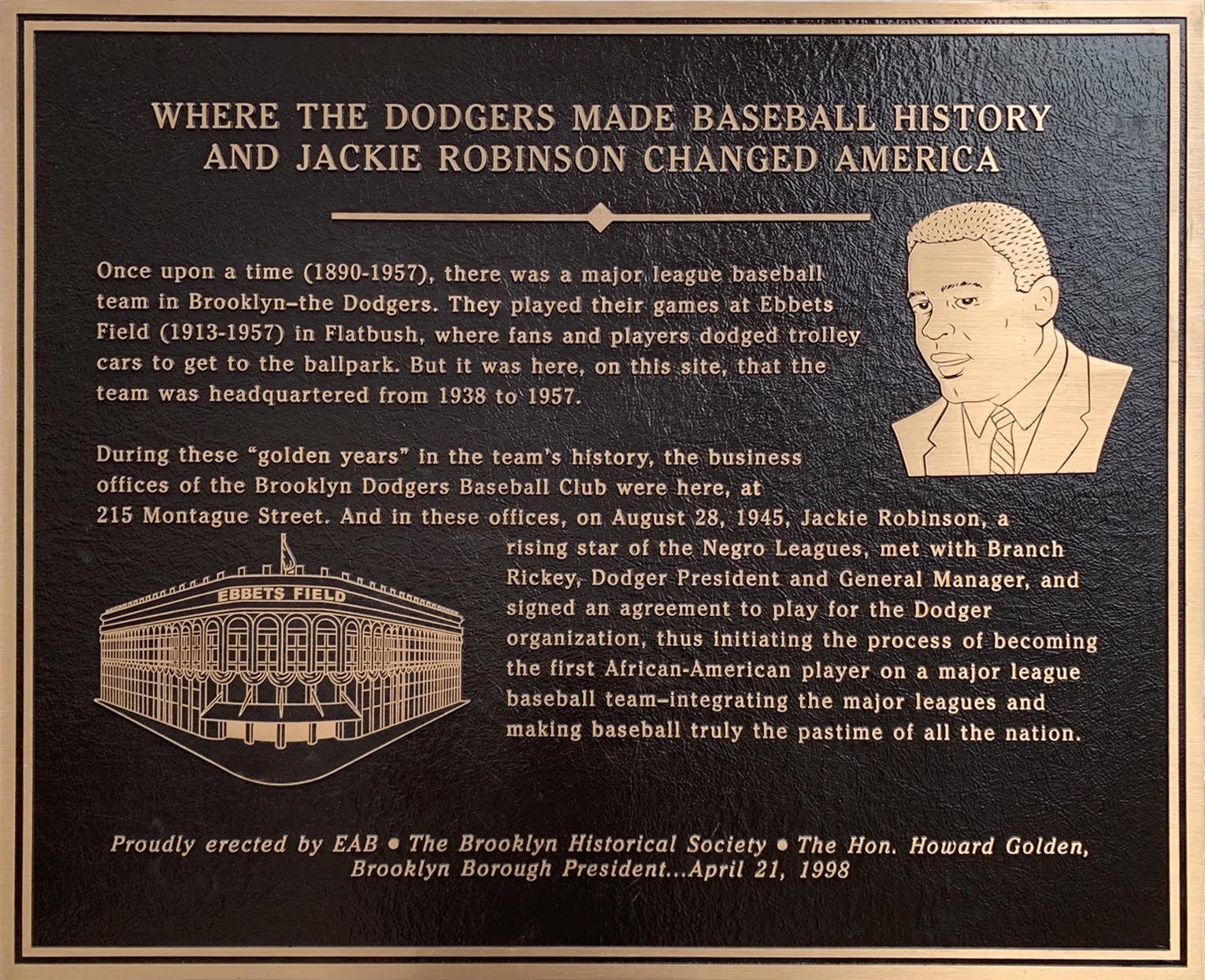

There were numerous reasons why October 1945 was an opportune time for Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey to sign Jackie Robinson to a minor-league contract. Nationally, World War II was over. More particularly, there was a growing understanding about the horrors of the Holocaust as well as the evils of discrimination. Further, many Americans were aware that Black men had put their lives on the line and some had died in the service of their country.

In New York state, the legislature had just passed the Ives-Quinn Law in July, creating the Commission Against Discrimination, with the power to fine and imprison violators. In New York City, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia had established the Committee for Unity, of which Rickey was a member. It helped to promote integration and provided a vehicle to support the new state law. Some mainstream sportswriters were now joining African-American and communist newspapers in calling for the integration of baseball.

As for the sport’s executives, the new commissioner, Albert Benjamin “Happy” Chandler, a southerner, had seen his power reduced, especially after he had overstepped his boundaries during the World Series, creating rumors the owners might buy out his contract. Besides, he had little, if any, authority to stop the signing. National League president, Ford Frick, was likely already aware of Rickey’s announcement but had no role at this point. Finally, both the Brooklyn Dodgers and Montreal Royals front offices were on board, thanks to Rickey’s efforts.

There did remain one potential obstacle. W.G. Bramham, president of the National Association of Professional Baseball Leagues, had the authority to sign off on all player contracts in the minors. While Rickey and he had interacted for many years, their relationship offered no guarantee of his support. Like commissioner Chandler, Bramham grew up in Kentucky. He attended college at the University of North Carolina and then practiced law in the state, based in Durham. He had spent his life in the South. Like Rickey, he was a Republican, but unlike the Dodger general manager, he was a strong believer in the “separate but equal” concept. He considered Rickey a “Moses for the Negro” and a “carpet-bagger.” When interviewed after Robinson was signed, he made his views clear: “Why should we raid their ranks, grab a player and put him, his baseball associates and his race in a position that will inevitably prove harmful?”

Still, Rickey may have known something else about Bramham, that the league head intended to treat Robinson’s contract like any other. He would sign it. When further asked if he anticipated any difficulty when his organization met in December, Bramham replied: “I do not think it will take any action.” He was obviously confident of his position. Before the start of the 1946 season, Bramham had been the only remaining structural obstacle to Robinson’s debut in Montreal. He publicly assured he would not be. Still, he typified the more moderate side of those who would make Robinson’s debuts in both the minors and later the majors challenging ones.

— Dave Bohmer