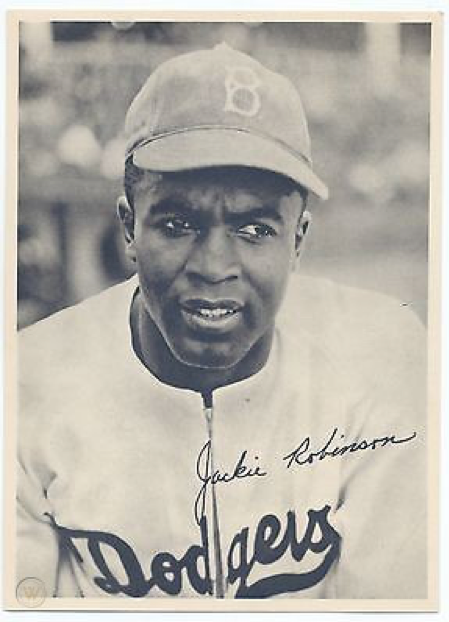

1947: Debut with the Dodgers

In 1947, Jackie Robinson joined a Brooklyn Dodgers infield that included, from left, third baseman John “Spider” Jorgensen, shortstop Pee Wee Reese, and second baseman Eddie Stanky. (SABR-RUCKER ARCHIVE)

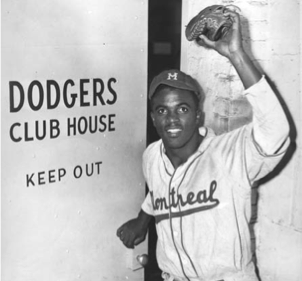

The 1947 season began with most people expecting Jackie Robinson to take the field in a Dodgers uniform. He played for the Montreal Royals in 1946 and led the International League in batting average and runs scored. He also led the league’s second basemen in fielding percentage. His numbers clearly dispelled any doubts that a Black player was not talented enough to play in the majors.

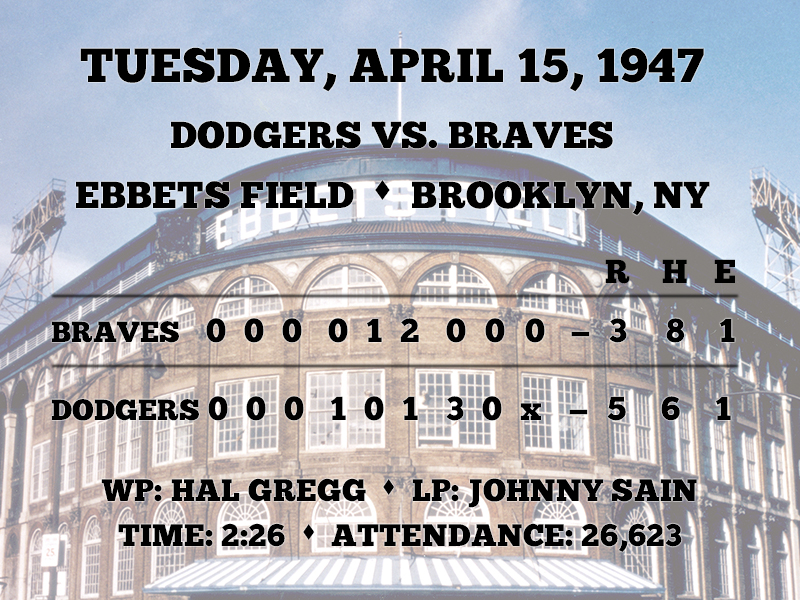

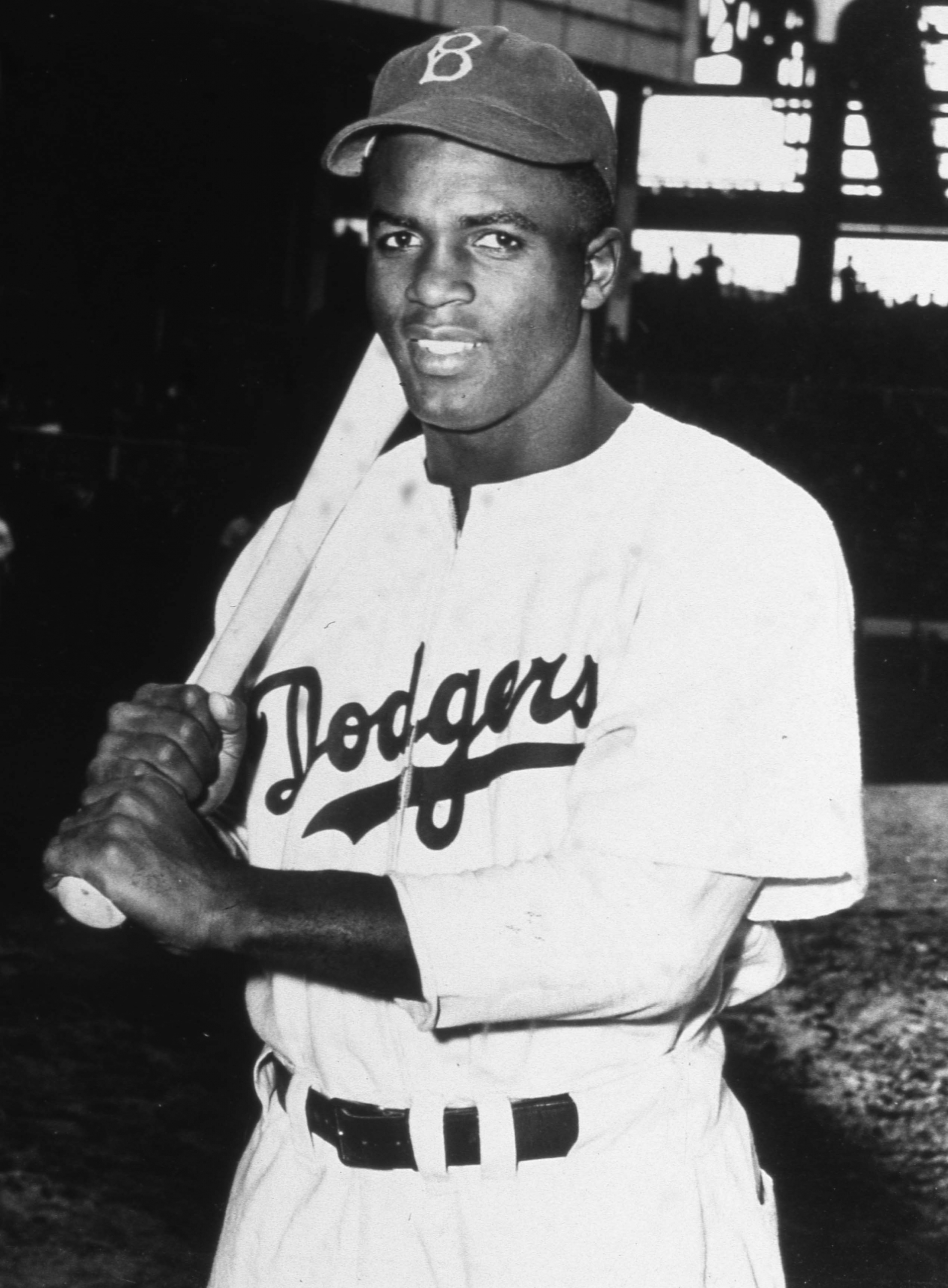

Robinson’s road to the major leagues happened quickly in the spring of 1947. Between April 10 and April 15, Robinson went from being a Montreal Royal to Brooklyn Dodger. Although Robinson didn’t get a hit in his first regular-season game on April 15, his bunt in the seventh inning gave the Brooklyn faithful a preview of the type of baseball that Robinson would play. Robinson notched his first hit two days later and his first home run on April 18 when the Dodgers faced the Giants, their crosstown rivals.

But just as quickly as Robinson demonstrated his skills on the field, he faced racial slurs from opposing teams. His worst experience that season came from Ben Chapman and the Philadelphia Phillies. Led by their manager, the Phillies verbally abused Robinson when they faced the Dodgers for the first time in late April. Robinson later admitted that this game was the most difficult one of the 1947 season. But the Phillies’ actions only strengthened public support for Robinson and eventually Chapman asked Robinson to pose for a photograph at Shibe Park, falsely giving the impression that there were no tensions between them.

Robinson’s play on the field, including a 21-game hitting streak in the middle of the season, showed that he belonged in the National League. But that did not stop the harassment from opposing players. Perhaps the most notorious incident came on August 20, when the Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter spiked Robinson in the 11th inning.

Despite all of the adversity, Robinson persevered. He led the NL in stolen bases and finished second in runs scored. He eventually earned Rookie of the Year honors and came in fifth in the MVP voting. “Robinson is everything that Branch Rickey said he was when he came up from Montreal,” said Dixie Walker, one of the Dodgers who were originally unwilling to play with Robinson.

It was only the beginning.

— Thomas J. Brown Jr.