Before Jackie: Baseball’s Color Line

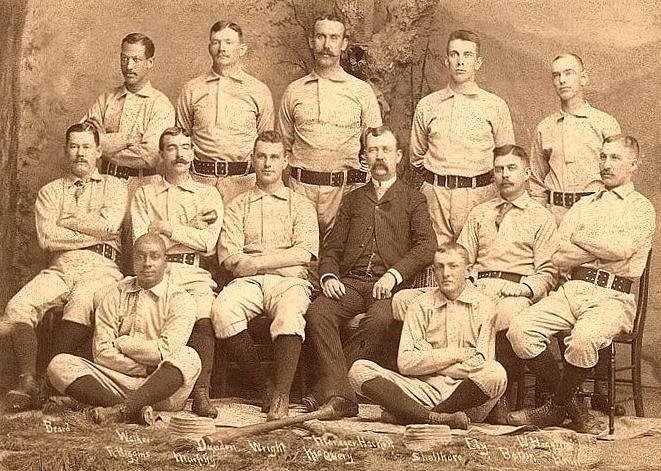

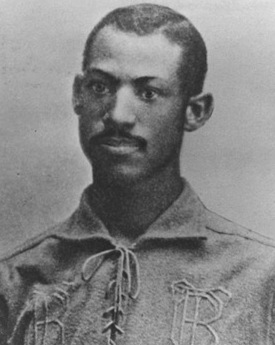

The 1888 Syracuse Stars included two Black players, catcher Moses Fleetwood Walker (top row, far left), and pitcher Robert Higgins (bottom row, far left). On July 14, 1887, International League owners voted to ban any future contracts with Black players. Fed up with the racism he had experienced in baseball, Higgins quit the team in midseason and Walker, the league’s lone remaining Black player, was released in 1889. No Black player would appear in an International League game again until Jackie Robinson with the Montreal Royals in 1946. (NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME LIBRARY)

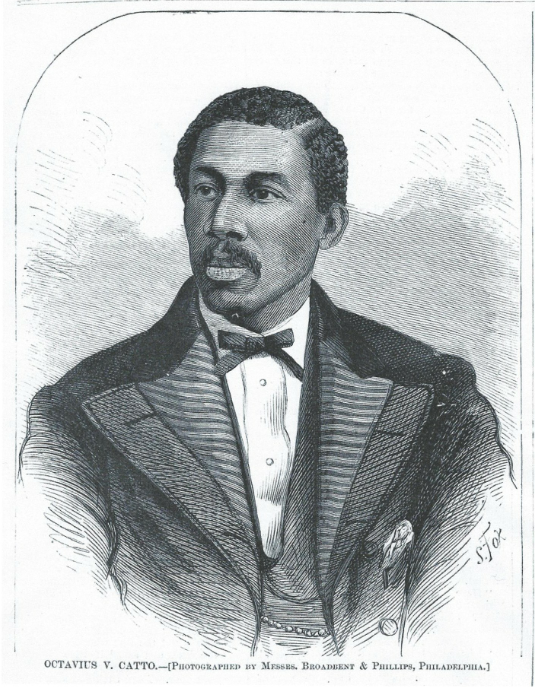

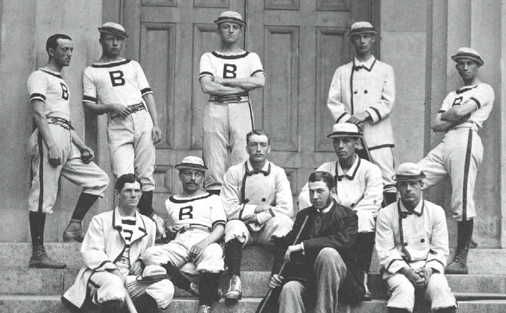

As we celebrate the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers, we need to look back at the history of the color line. As early as the 1860s, the Philadelphia Pythians were kept from playing in an all-White league. In the 1880s, Cap Anson and the Chicago White Stockings refused to take the field with Black players Moses Fleetwood Walker and George Stovey. In 1887, International League team executives voted to ban future contracts for Black players — and thus, the color line was born.

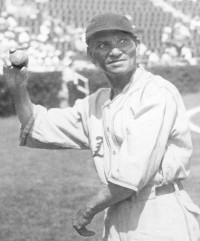

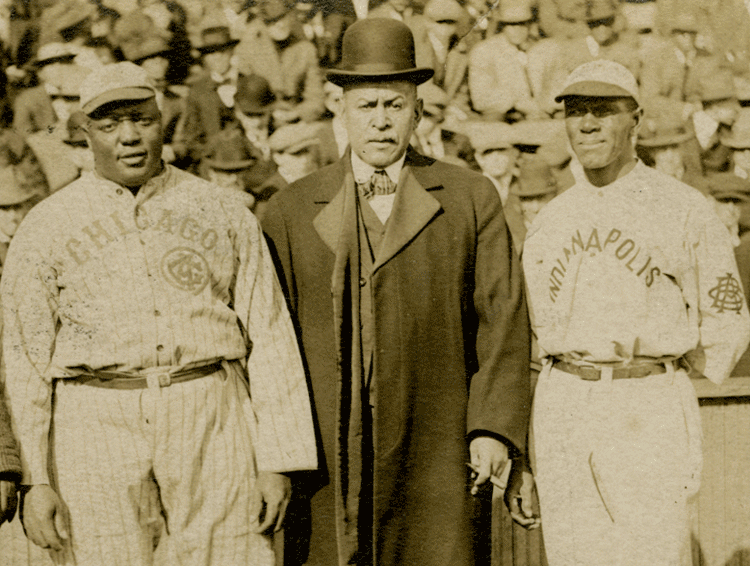

There were attempts from the 1890s to the 1940s to break the color line at the major-league level, but none succeeded. By the 1890s, most Black professional players had to play on all-Black teams, barnstorming across the country. Teams like the Cuban Giants, the Page Fence Giants, and the Chicago Unions played all comers, Black and White, but not in any major leagues. Black and White teams continued to play one another until 1947, but always outside the official channels of what was then considered Organized Baseball.

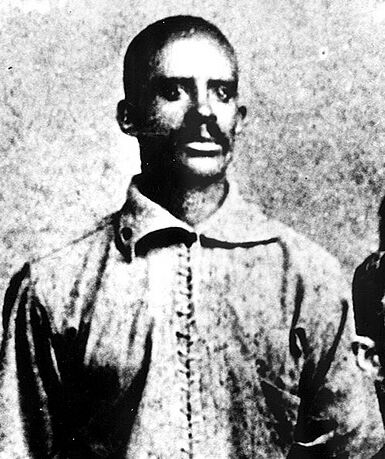

A few individual players, such as Jimmy Claxton and Charlie Grant, tried to break the color line unsuccessfully. Some Black teams played against White opponents in the prestigious amateur Denver Post Tournament and later for the US Navy’s Great Lakes team. These efforts did little to change the racial attitudes present in baseball.

Some players were invited to tryouts with big-league clubs in the 1930s and 1940s. None of these opportunities dented the color line. Sports writers Wendell Smith, Fay Young, Sam Lacy, and Joe Bostic pushed to make many of these efforts happen, but were disappointed with the lack of follow-up by the Pittsburgh Pirates, Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Boston Braves and Red Sox.

Sports writers were not the only ones pushing for change. Communist Party organizations and newspapers such as The Daily Worker took up the call for ending the color line to no avail. World War II caused some people to question the idea of men going to die for their country but not being able to play baseball together. Branch Rickey founded the United States League in 1945 as a way to begin looking for a player to break the color line. His efforts led to the signing of Jackie Robinson to a contract with the Dodgers organization, resulting in his debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947. Robinson’s debut finally broke a color line that had existed since just after the Civil War.

On this page, enjoy learning more about the players and figures who helped pave the way for Jackie Robinson to make his debut with the Dodgers in 1947.

— Leslie Heaphy