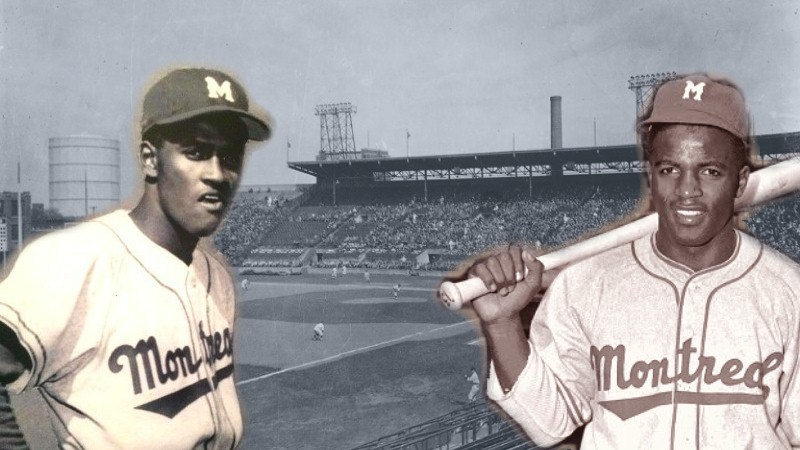

1946: Integrating the Minor Leagues

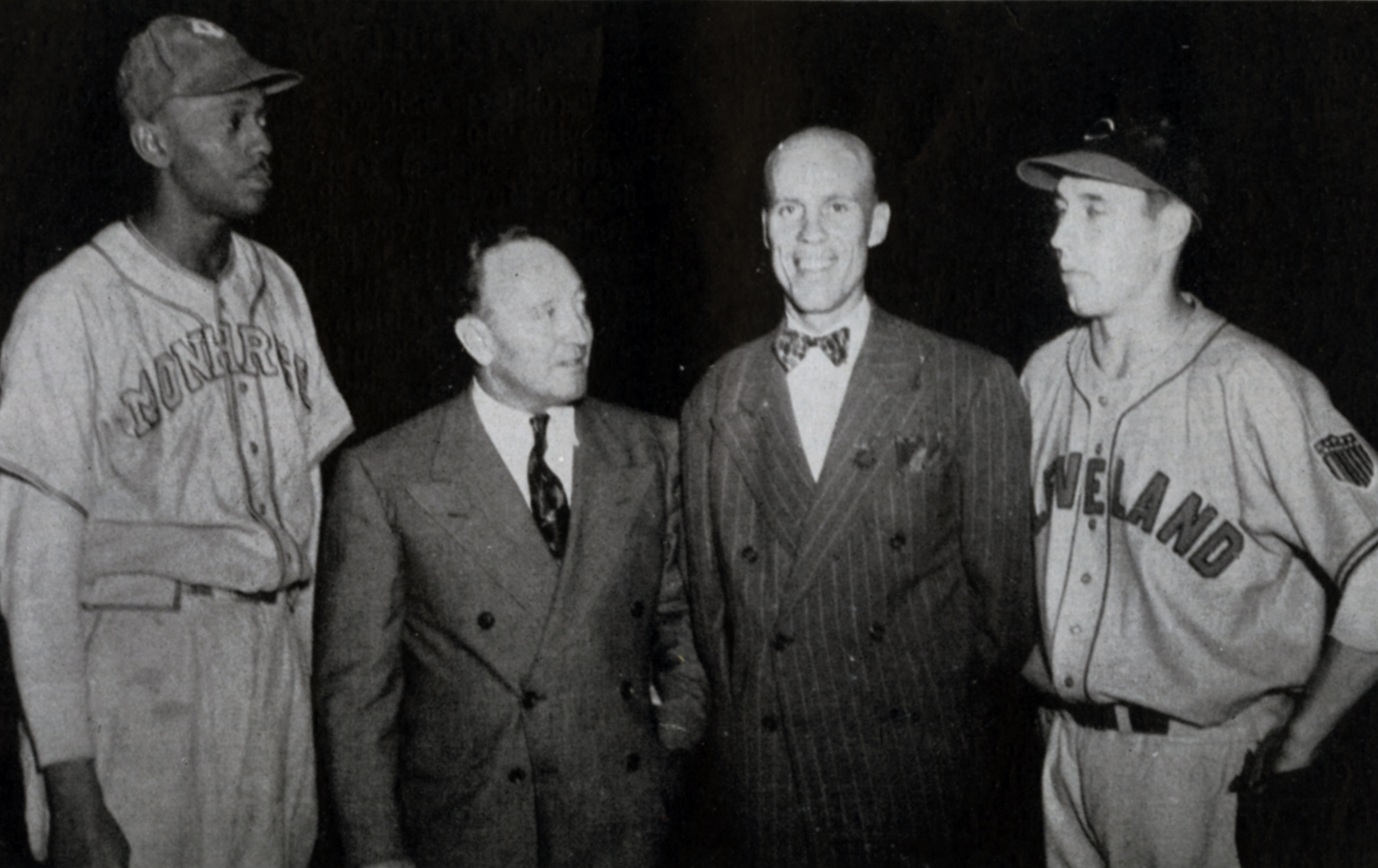

George Shuba, right, greets Jackie Robinson at home plate on April 18, 1946, after Robinson homered in his debut with the Montreal Royals of the International League. (Courtesy of Greg Gulas, Carrie Anderson, Mike Shuba)

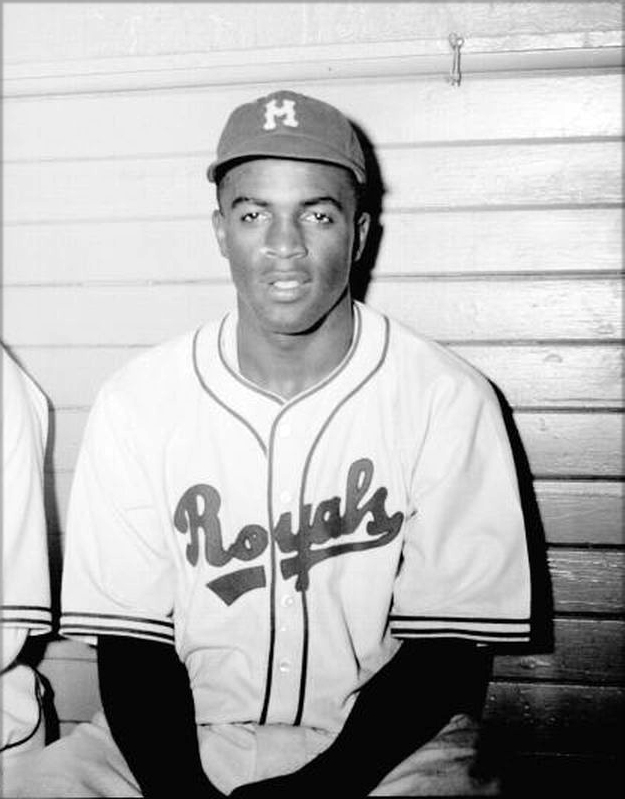

A lot has been written about Jackie Robinson’s Hall of Fame major-league career. However, authors tend to gloss over the crucial 1946 season he spent with the Triple-A Montreal Royals. That season was every bit as important — if not more important — than Robinson’s first year as a Brooklyn Dodger. It might also have been the most trying of Robinson’s career.

After he signed a contract with Montreal, The Sporting News deemed baseball integration “impractical, if not impossible.” By the fall of 1946, through sheer talent and determination, with his wife Rachel by his side and with the unwavering support of Montreal fans, Jackie Robinson had made integration seem more inevitable. In those first few months, he deconstructed every argument that had been used to keep the sport segregated for close to six decades. But the road to get there was extremely rough.

Spring training in Florida proved especially challenging. Just traveling to the Sunshine State from his home in California was difficult. Once he arrived, he struggled to learn a new position, he didn’t hit well, he got hurt — and that was happening against the backdrop of possible violence and threats of lynching.

Robinson was able to put the hardships of spring training behind and exploded onto the scene in his first regular season game in “white” baseball. He then spent the rest of the year proving those who thought African Americans did not possess the right makeup to play big-time baseball wrong. Dodgers president Branch Rickey had ordered him never to respond to provocation. Despite the insults raining down from the stands or the opposing dugout, the pitches thrown at his head, the attempted spikings at second base, Robinson kept on going.

The abuse he was taking, combined with the crushing pressure he felt to be perfect on and off the field, took their toll. By mid-August, he was burned out and ordered to rest by doctors. But the team depended on its star second baseman. He had to keep going. Robinson somehow managed to play at a high level for another month and a half until the Royals were crowned champions of the Junior World Series. The “Great Experiment” of integrated baseball was an overwhelming success. Black players could play in “white” baseball. Integrated teams could be winners.

That magical season marked the beginning of a love story between the Robinson family and the city of Montreal that is still going strong more than seven decades later.

— Marcel Dugas