Wrigley Field (Los Angeles)

This article was written by Jim Gordon

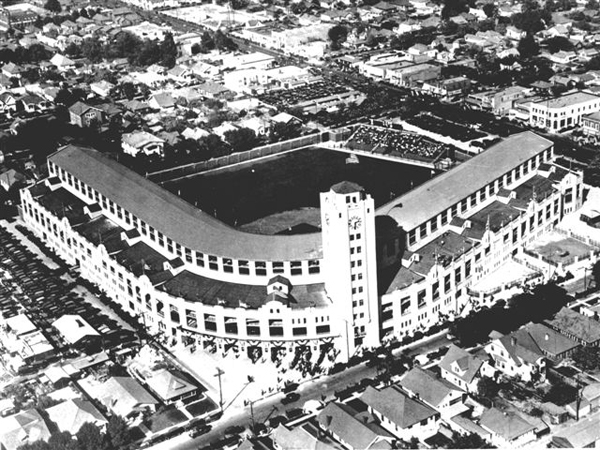

Los Angeles’s Wrigley Field in was built and opened in 1925 as the finest minor-league park in the country. Some called it the best park in the country — majors or minors. From its earliest years Wrigley Field was home to multiple baseball teams, many other sports and community events. The history of Wrigley Field is rich and intermingles with the history of its city. It played host to the fiercest rivalry in minor-league baseball between the Pacific Coast League (PCL) Los Angeles Angels and Hollywood Stars. After more than 32 years of PCL baseball, Wrigley closed its professional baseball doors for three years in 1958, before being reborn for the 1961 American League season as the home of the American League’s new Los Angeles Angels.

In its lone major-league season of 1961, a record was set for the most home runs hit in a ballpark during a season, a record that lasted 35 years. Also, the popular TV show Home Run Derby was filmed at Wrigley because of its proximity to the studios and its proclivity for home runs. Wrigley Field was also shown in many motion pictures; the most notable were the 1949 film It Happens Every Spring with Ray Milland, Fear Strikes Out in 1957 and Damn Yankees in 1958. After the 1961 season, Wrigley survived for another seven and one half years as a community and sports resource until its demolition in March of 1969.

The 1920s — Birth of Wrigley Field

William K. Wrigley, Jr., chewing gum magnate and principal owner of the National League’s Chicago Cubs, purchased the Los Angeles Angels of the Pacific Coast League in 1921. After a dispute with the city over parking at the club’s Washington Park facility, Wrigley decided to erect his own ballpark. In August, 1922, Wrigley announced that he had secured an option on a site for a new ballpark on an area bounded by 39th Street, South Park Avenue and 41st Street. He promised a ballpark where local fans would be able to enjoy baseball in the luxury to which major-league rooters are accustomed. He also promised ample parking which never materialized. Wrigley hired architect Zachary Taylor Davis, who had designed both Cubs Park (later named Wrigley Field) and Comiskey Park in Chicago, to design the nation’s finest minor-league ballpark. He also instructed Davis to pattern the park after Cubs Park both as it was and as Wrigley wanted it to be.

In December 1924, J. H. Patrick, President of the Angels and Wrigley’s western representative, announced that ground for the new park would be broken in February and it would be ready for the 1926 season. In January, they started taking bids for materials. Davis’s design used iron and steel construction which was then common for major-league ballparks but much less so for the minors. He also designed a covered, double-decked grandstand from foul pole to foul pole which was very unusual for the minor leagues. Cubs Park was not double-decked until after the 1926 season. Davis’ new park seated about 18,500 in the grandstand and an additional 2,000 in the right field bleachers and was slightly larger than Cubs Park. Davis and the general contractor, A. Lanquist, visited the site in March. They found that some of the ground was unstable and part of the park would require sinking pilings. It was learned that the site was at the head of a former river. This increased the cost by $100,000.

The Angels opened the 1925 season at Washington Park before a crowd of 15,000, the largest in nine years. This impressed William Wrigley and he ordered the work on the new park accelerated to open on August 4 against Salt Lake City. Because Wrigley consistently ordered Davis to spare no expense, the projected cost of the park passed $1,000,000 in June. Work was delayed because all of the 2,200 tons of steel was not delivered on time. The opening date was moved to September 16 against Seattle. By June 20, the steel had been delivered, all the boxes were up, and the playing field, which was sodded months before, was in wonderful condition. By August 15, the park was nearing completion but would not be ready for September 16. The steel structure was erected and almost all the cement was poured. All that remained was finishing the cement work, painting the plant and installing chairs. A 150-foot, nine story tower was one of the unique features of the park. Wrigley debated whether to open for the last three weeks of the PCL season or wait until 1926. If the park did not open this season, it was understood it would be dedicated the following January, when the annual minor-league convention was to be held at Catalina Island.

On September 19, the Angels announced that the park would open for the San Francisco Seals series on September 29. Before leaving for the East, Wrigley said that he would not allow the Vernon Club to play in his park the next season. Vernon and the Angels had been sharing Washington Park. Efforts were being made to have continuous baseball in the new park and it was believed satisfactory arrangements could be made during the winter.

Wrigley Field was dedicated and opened on September 29, 1925 with the Angels defeating San Francisco 10-8 before 18,000 fans. Hal Rhyne, Seals shortstop, got the first hit on the sixth pitch of the game and scored the first run on a sacrifice fly by Frank Brower. Paul Waner of the Seals hit the first home run in the third inning over the right field wall. Arnold “Jigger” Statz hit the first double and Wally Hood hit the first triple. Doc Crandall got the win and Jeff Pfeffer the loss. Statz hit for the cycle. Mayor George Cryer threw out the first ball to Sheriff Bill Traeger with Harry A. Williams, President of the Coast League as umpire. Catalina Island’s 50-piece band was brought over for the festivities. As an omen of the later major-league record, there were four home runs in the game. It was the first ballpark to be called Wrigley Field as the Cubs ballpark was not renamed Wrigley Field until the 1926 season. The park was dubbed “Wrigley’s Million Dollar Palace.”

At the close of the PCL season in October, The Sporting News was glowing in their praise of Wrigley. They called it a “real monument to the national game” and the “general appointments of new plant set pace even for big leagues”, continuing:

At the close of the PCL season in October, The Sporting News was glowing in their praise of Wrigley. They called it a “real monument to the national game” and the “general appointments of new plant set pace even for big leagues”, continuing:

“Major league baseball owners will not be prone to boast about their beautiful parks when they see the one William Wrigley, Jr., has given the fans of this city. Many of them will be compelled to admit that the magnificent structure now used for the Los Angeles Baseball Club has something on theirs in every respect. They will also be forced to acknowledge that Wrigley has erected the finest baseball edifice in the United States. It is too big for a minor league, is a remark that generally comes from those seeing Wrigley Field for the first time. Minor league parks are on the average so small that it is impossible for many to conceive what the Los Angeles Club is going to do with a plant of that magnitude. But that is the way things are done in this part of the country, especially by Wrigley. There is no doubt about the Los Angeles Park being a major league plant and then some… Wrigley Field is a picture. Architecturally it is in a class by itself. Money was not spared in making it the finest. Few parks in the country cost more. Wrigley put no limit on the expense in building it. It was not his desire, however, to make it a better plant than the one the Cubs, his other club, uses in Chicago, but that has been done. Cubs park is an excellent one, but the Angels have a better one. It is a double decker, having a seating capacity of approximately 20,000. One of the pleasing features of the field is that every seat affords a real view. Besides, there are nearly 8,000 box seats, so that the fans who are given to getting to the park late have no difficulty is securing a choice seat… The erection of Wrigley Field entailed a cost of $1,5000,000. It is not as large as the Polo Grounds or Yankee Stadium, but it is prettier. It is a park that is pleasing to look at, not only on the outside but also on the inside. There is not a sign in or outside of the park to mar the beauty of the architecture. The park has a tower 150 feet high on which has been installed clocks on the four sides. These clocks measure 13 foot in diameter and can be seen from all parts of the city.” The numerals on the clock spell out Wrigley Field. “The offices also are handsomely decorated, are extremely light and airy and command a view of the city that cannot be seen from any other point. The offices are reached by an elevator that also goes to the top of the tower where an observation platform has been constructed from which one can see the beautiful mountains of Southern California, all the adjoining suburbs and the ocean.”

“In constructing Wrigley Field, Davis did not overlook the players. He planned an outlay of club houses that is excelled by none in the United States. The shower rooms have six individual sprays, there is a separate rubbing room for the trainer and first-class toilets. Besides, the locker rooms are spacious, light, well ventilated and a clothes dryer has been installed in each of the three clubhouses. There are three because two clubs will occupy Wrigley Field, and one is for the visiting team. Each has the same excellent accommodations. Owing to the plasticity of the baseball used today there has been a cry for larger playing fields. Wrigley Field is arranged to take care of as lively a pellet as the makers care to put forth. The playing field is one of the largest in the country measuring 345 feet from home plate down each foul line to the fence and 427 feet to a point in center field. This area gives the outfielders ample room in which to show their fleet footedness and to roam for long drives that are hammered out by the vigorous sluggers. Home runs have been made in the park since the Angels started to play in it, but those making them earned and were entitled to them.”

Clearly, The Sporting News missed the shortness of the power alleys. In later years the left field wall was covered with ivy to emulate Chicago’s Wrigley Field and there was a picnic area for fans next to the bleachers behind the right field wall. Wrigley also promised to spend whatever it took to make Los Angeles a winner. He came through on this promise the following year.

From the beginning Wrigley was a community resource. The first “professional” football game played at Wrigley had the Los Angeles Athletic Club with six former All-Americans defeating the USS Idaho 21-7 before 2,000 in December. On January 15, 1926, dedication ceremonies were held for the clock tower at Wrigley Field, with Judge Landis, baseball’s commissioner, as the speaker, the event sponsored by the American Legion. J. Cal Ewing, owner of the Oakland Oaks, presented the bronze tablet which was accepted by John Quinn, former National Commander of the American Legion. William Wrigley Jr. came from Catalina to attend. The plaque read: “This tower was erected by W. K. Wrigley, Jr., in honor of the baseball players who gave or risked their lives in defence of their country in the Great World War.”

For the 1926 season, the PCL’s Salt Lake City franchise moved to Los Angeles as the Hollywood Stars (also called the Sheiks which was the Hollywood High nickname) and shared Wrigley with the Angels. With a monthly upkeep cost of $13,000, Wrigley wanted another tenant and Los Angeles wanted continuous baseball. The Chicago Cubs became the first major-league team to play in Wrigley Field, losing the spring training opener to the Angels 5-2 before 3,000 under threatening skies on March 5. Before the start of the regular season, J. H. Patrick, president of the Angels, and Bill Lane, owner of the Stars, agreed that ladies would be admitted free for all games. Previously, ladies had been admitted free except on Saturday and Sunday. When 2,500 ladies out of a crowd of 15,000 attended a Sunday exhibition game against the Pirates, Saturday and Sunday were included in the benefit. The Stars first game at Wrigley was a 6-2 win over the Angels before 10,000 on April 13. Richard McCabe was the winning pitcher and Lefty O’Doul hit a three-run home run in the first inning.

This began the first incarnation of the most heated rivalry in minor-league baseball between the Angels and the Stars. William Wrigley came through on his promise to deliver a championship as the Angels won the PCL pennant by 10½ games. On October 19, they played a charity exhibition for the Association of Professional Ball Players of America against Irish Meusel‘s all-stars including Tony Lazzeri, Babe Herman and Fred Haney. Jigger Statz and Fred Haney made spectacular fielding plays. For the 1926 season, Statz had led the PCL with 291 hits, 68 doubles and 18 triples.

After much contention and many delays, Dick Donald staged the first boxing card at Wrigley Field in 1926 with three 10 round fights starting at 2:45 on October 23. In the main event, middleweight Bert Colima defeated Everett Strong. The first high school football game was held at Wrigley on October 29 with Polytechnic defeating their arch rival, Lincoln, 32-0. Fall exhibition baseball with major-league players was often at Wrigley. The 1927 movie, The Bush Leaguer was the first of many films to use Wrigley Field.

The first 20,000 crowd at Wrigley attended the Angels-Stars doubleheader on April 16, 1928 with the Stars wining the first game 8-4 behind spitballer Frank Shellenback and the Angels the second 4-0 on Doc Wright‘s shutout. This was the second largest crowd in PCL history. About 3,500 ladies in spring attire and new hats took advantage of the free admission policy for a Saturday game against Oakland in April.

In 1929, Hollywood won its first PCL pennant in the split season format that started in 1928. They won the second half and defeated the Missions four games to two in the playoff. The final game, before 15,000 at Wrigley, was won 8-3 after a five-run eighth inning behind Frank Shellenback who also homered.

The 1930s — Lights, Depression, a Great Team and a New Rival

The major milestone of the 1930 season was the installation of lights. In early May, Des Moines of the Western League had introduced lights and night baseball. Sacramento was the first PCL team to use lights on May 22. The first night game at Wrigley was played on July 22 with the Angels defeating Sacramento 5-4 in 11 innings before 17,000. The game was sent into extra innings when Jigger Statz dropped a line drive to left allowing the tying run to score in the ninth, but he became the hero when he tripled in the winning run in the eleventh. By August, all weekday games were at night. Hollywood and Los Angeles battled the entire 1930 season for the PCL title. The Angels won the first half with the Stars second and these positions reversed in the second half. The two clubs drew more than 850,000 fans to Wrigley that year beating the two major-league teams in St. Louis in attendance. A series in September between the Angels and Stars drew 79,941. The Stars won the playoff four games to one.

In 1931, Hollywood won the first half but faded to fifth in the second and lost the playoff four games to none in their try at a third consecutive title. The New York Giants arrived on February 18, 1932 for spring training, the first major-league team to train in Wrigley Field. The Giants compiled an 8-3 record at Wrigley against the Cubs, Tigers and Pirates. The maximum attendance was 10,500 for a Sunday game against Chicago. John McGraw stated that despite poor attendance, he was bringing the Giants back in 1933 because, with perfect weather, they lost no training days to rain. The Angels trained at Brookside Park in Pasadena. The New York Giants returned in 1933, but were hampered by the Long Beach earthquake and very poor attendance and did not return.

On September 6, 1933, the all-time Pacific Coast League attendance record of 24,695 was set for a Wednesday night double header between the Stars and the home-team Angels. The Angels won the opener 2-0 behind Buck Newsom’s 26th win and 8th shutout; the second game was called due to fog in the fourth inning with the Angels leading 5-4. The paid attendance was 15,231 with an additional 9,464 women or free passes. Ticket sales were halted at 7:00, 30 minutes before game time. The Angels won the 1933 PCL pennant but the Great Depression was hitting the area hard. Ticket prices at Wrigley were reduced to 85 cents for a box seat, 60 cents for reserved and 25 cents for the bleachers and overall attendance dropped

In 1934, the Angels had the greatest record in PCL history — winning 137 games and losing 50 for a .733 percentage. They won the first half by 18½ games and the second half by 12. On May 29, they overcame a 6-1 Hollywood lead with three runs in the eighth inning and another three runs in the ninth. The next day, Memorial Day, the Angels swept a double header from the Stars, 6-5 in 11 innings and 1-0, before 20,000. At the end of the season, the Angels played a league all-star team at Wrigley Field. The games were not on the radio and fans were advised to attend. The receipts of the series were split with 60 percent going to the winning team. The Angels won the series in six games after falling behind two games to one. The last game was a 4-3 Angel victory coming from behind again with two runs in the eighth and one in the ninth inning. The five dates drew about 30,000 fans.

Hollywood had been losing money for several years and drew less than 90,000 paid fans in 1935. After the season, Bill Lane moved the team to San Diego to become the Padres. His move was predicated by Dave Fleming, President of the Angels, who doubled Lane’s $5,000 rent. The last date for Hollywood at Wrigley, September 22, was a doubleheader with the Stars beating the San Francisco Missions 8-7 in the opener and losing the night cap 14-7 with a crowd under 2,000. Actor/comedian Joe E. Brown amused the fans by umpiring at first and third bases in the second game and finally taking the mound for the Missions with two out in the seventh inning to strike out composer Harry Ruby to end the game with his infielders and outfielders sitting by the mound. Ruby played the four innings at second base for Hollywood.

The Angels had the city and Wrigley Field to themselves for two years. Many of the Hollywood fans could not root for the Angels and there was substantial support for a second Los Angeles team but the Angels did not want to share Wrigley. Moreover, the Missions were failing in San Francisco. The PCL developed a compromise solution. The Missions would move to Los Angeles and play in Wrigley Field for one year while the San Francisco owners tried to sell the team to Los Angeles interests. The new Hollywood Stars played their first game at Wrigley against the home-team Angels on April 2, losing 6-5 before 15,000 to open the 1938 season. The Hollywood Stars played their last home games at Wrigley on August 30 by splitting a double header with Seattle losing the first game 9-2 and winning the finale 11-2 before 11,000. The Angels finished first in the PCL but lost to Sacramento in the President’s Cup playoffs. For the playoffs at Wrigley, ticket prices were $1.10, $0.80 and $0.40 for box seats, grandstand and bleachers, respectively.

On January 15, 1939, the National Football League champion New York Giants beat the All-American Stars 13-10 in the first Pro Bowl before about 20,000 fans. Wrigley Field was used because the Los Angeles Coliseum Commission would not allow professional sports. Mayor Bowron and the city became infuriated when the Commission granted a permit “for airing of the views of a convicted dynamiter, notorious radical and associate of anarchists” at the same time the game was to be played. After World War II, the Pro Bowl became a fixture at the Los Angeles Coliseum until later moving to Hawaii.

The first of two World Heavyweight Championship boxing matches held at Wrigley took place on April 17, 1939. Joe Louis knocked out Jack Roper in 2:20 of the first round retaining the title before a crowd estimated between 23,000 and 30,000 including many gate crashers. The “official” attendance was 21,125 and the gross gate was $87,679.75. Mike Jacobs was happy with the event and said he would schedule more championship fights in Los Angeles if the Coliseum would allow professional sports.

In 1939 Bob Cobb of the Brown Derby restaurant took over the Stars and built a new ballpark, Gilmore Field, next to the Farmer’s Market. The Angels again had Wrigley Field to themselves.

The 1940s — Almost Major League Baseball, the War and PCL Glory Days

In 1940, the Angels opened on the road, in San Diego, for the first time since the PCL was formed in 1903. The Stars were given opening day at home at Gilmore Field which had not been ready for the start of the 1939 season. Jigger Statz took over as player-manager of the Angels.

After the 1941 season, major-league baseball almost came to Los Angeles and Wrigley Field. At the baseball winter meeting held at the Palmer House in Chicago beginning on December 9, the American League unanimously voted down an unnamed proposal made to Don Barnes, president of the St. Louis Browns, to move the club to Los Angeles and play in Wrigley Field. The Los Angeles Times reported “That the old gag about bringing major league baseball to Los Angeles was reborn at the American League meeting in Chicago yesterday, but it lived a brief life.”

Los Angeles, Sacramento and Seattle battled all through the 1942 season for the PCL pennant. On May 17, the Angels and Rainiers split a double header at Wrigley before 15,905 paid plus 600 servicemen. This was the largest Wrigley crowd in 10 years. Seattle won the opener 3-1 in 14 innings and the Angels won the second game also 3-1 which was shortened to five innings by agreement so the teams could catch a northbound train.

On August 4, the Army restricted night lighting along the Pacific Coast from Canada to Mexico and as far inland as 150 miles. Although the order did not go into effect until August 20, the Angels played the last night baseball game on August 7 through the end of the 1943 season. Jack Salveson pitched the Oakland Oaks over the Angels 6-1. The 3,500 fans bid goodbye to night baseball after the seventh inning when all the lights were extinguished and the fans stood and held lighted matches during the sounding of taps and the singing of the national anthem.

Because of the war, the 1943 season was shortened to 155 games and the night baseball ban remained. The Angels won the pennant by 21 games over San Francisco. Large crowds showed up at Wrigley for two double headers. On May 23, 19,000 saw the Angels and Stars split a double header with the Angels winning the opener 5-1 and the Stars coming back with 5 runs in the seventh inning to overcome a 4-1 Angel lead and win 6-4. On June 28, the Angels and Seals split a Sunday double header before 19,132, the largest daytime paid crowd in Wrigley history. The Angels won the series six games to one and drew 31,333; this pushed the attendance for the first four series of the year to 115,000. The Angels won the PCL again in 1944. More and more players were entering the military and the quality of baseball suffered

In 1946, there was talk of the PCL becoming a third major league because of stadiums like Wrigley and Seals Stadium and the growing population on the west coast. With the war over, crowds flocked to the ballparks. The Angels drew a record 501,259 at Wrigley while finishing in the middle of the pack. This was the start of booming glory days for the PCL.

The Angels and Seals battled for the PCL pennant all through the 1947 season and, for the first time ever, finished in a flat-footed tie. A one game playoff was scheduled for September 29 at Wrigley Field. 22,996 fans jammed the field for the game and thousands were turned away when fire marshals banned further ticket sales hours before game time. There were standees all over the place but none on the field for this game because of official objections. Lefty Cliff Chambers started for the Angels in search of his 24th win. Righty Jack Brewer started for the Seals. There was no score in the bottom of the eighth. With one out and the bases loaded, cleanup hitter Clarence Maddern came up and hit the first pitch far over the left field wall. The team mobbed Maddern at home plate. With two out, Larry Barton hit a ball into the bleachers for a 5-0 lead. Chambers closed out the ninth for a 5-hit shutout. The Angels received $15,000 to divide for winning the league and another $15,000 for winning the playoffs, now called the Governor’s Cup. This is often considered the greatest game in Wrigley Field history. Home attendance reached 622,485, the Angels all-time record. Near the end of the 1947 season, the Angels televised their first game. No one knew that this would be that start of a downhill slide for minor-league baseball.

The Angels slipped to third in 1948 but home attendance was a robust 576,372. By the middle of 1948, all weekend games were on television and more weekday games.

The desire for major-league baseball in Los Angeles was demonstrated at Wrigley Field on March 20, 1949. The defending World Champion Cleveland Indians played the Cubs in a spring training game before 24,517 paying customers. It was the second greatest crowd in Los Angeles baseball history. The Cubs won 3-2 in 10 innings. The quality of play was excellent and few of the thousands who were corralled along the outfield wall or standing at the back of the grandstand left before the finish. The fans were treated to seeing both Bob Feller and Bob Lemon pitch.

In 1949, Hollywood hired their radio broadcaster, Fred Haney, as manager, developed a working agreement with the Brooklyn Dodgers and rose to the top of the PCL. The Angels sank to last place and attendance dwindled to just over 400,000. However, on May 15, the Padres and their rising star, Luke Easter, drew the largest paid crowd ever at Wrigley, 23,083, for a double header. The Angels won the first game 8-7 though the Padres protested when Easter was called out on a pickoff at first base that was followed by a home run. He was originally called safe because the ball was not in play, but, after the three umpires had a long discussion, the call was changed. The Padres won the second game 13-1.

The 1950s — Television, Decline, Bilko and Major League Baseball in Los Angeles

In the early 1950s, television became pervasive in American society. Many families were getting television sets and the popular shows of the day were embraced by the culture. People stayed home to watch television and the entire entertainment industry suffered. Movies, nightclubs, theater and sports attendance all declined. Moreover, as the major leagues began televising games, the interest in the minor leagues declined drastically and many leagues folded. One can imagine the difference in interest in watching a major-league game live on television as compared to listening to a minor-league radio recreation, sometimes hours after the game was completed. Live major league radio, The Game of the Day, also hurt the minor leagues.

The PCL, despite its near major league status, was no exception. As more games became televised to spur interest and generate additional revenue, attendance declined. The problem was compounded for the Angels. The Stars were managed by the popular Fred Haney and then by the flamboyant Bobby Bragan. The Stars became a Pittsburgh farm team and prospered; they finished ahead of the Angels every year from 1949 through 1955. The Angels were owned by the moribund Cubs who could not provide the top caliber talent. In 1950, the Stars introduced playing day games in shorts which caused a major stir throughout baseball. Thus, the Angels had substantial problems keeping fan interest and attendance at Wrigley Field.

On December 9, 1951, the major leagues defined the requirements for an “Open Classification” rating for a minor league and the path by which major-league status could be attained. The PCL was the only league to qualify. To become a major league, the PCL would have to substantially increase attendance and implement park upgrades to 25,000 seating. The classification did allow the PCL to pay higher salaries and keep players who might have gone to the majors. The PCL never came close to meeting the requirements for major-league status.

Despite the problems, there were some memorable moments, primarily between the Angels and Stars. On April 7, 1952, 23,497 fans attended the Hollywood 6-5 win over the Angels in the largest paid crowd for a PCL game in Los Angeles surpassing 23,083 for an Angel-Padre double header on May 15, 1949 and second only to 23,603 for a San Francisco-Oakland game in 1946. Thousands were turned away and the “Ladies Night” game was delayed 10 minutes because of a traffic jam outside the stadium. Hollywood swept a double header from the Angels 12-8 in 10 innings and 5-1 before 17,517 fans who rioted during the first game on August 10. Home plate umpire Ed Runge called the Stars’ Jim Magnan safe at the plate on a close play in the 10th inning and cushions and debris were thrown from the stands during a prolonged beef by Angel’s manager Stan Hack and one fan charged onto the field. After the bottom of the 10th, another fan attacked Runge and wrestled him to the ground. He was pulled off Runge and pummeled by infielder Gene Handley of the Stars. The Angels made seven errors to compound their frustration.

The second game was played with 35 extra police patrolling the field and the stands under the personal direction of Los Angeles Police Chief William Parker. Johnny Lindell outpitched Joe Hatten for the Stars victory on their way to the PCL pennant. Attendance for the 8-game series was 85,181, a Wrigley Field record and brought the Angel attendance to 405,572 gross, although the paid attendance was much less.

The question of how to bring major-league baseball to Los Angeles persisted and presented the classic chicken and egg problem. No team would come without a major-league stadium and no one would create a major-league stadium without a team. Many thought that Wrigley Field could be upgraded to 40,000 to 50,000 seats. However, this would entail condemnation of private housing and businesses around the stadium and could not be accomplished quickly.

Phillip K. Wrigley, owner of the Cubs and Angels, knew that he would not pay for the upgrades although he promoted them. In late 1954, Wrigley quietly hired Bill Veeck to sell Wrigley Field at a large profit. Veeck had the reputation of being able to sell anything to anybody. However, Veeck failed to unload Wrigley at a price satisfactorily to Wrigley. Would you have bought a used stadium from that man? Ned Cronin, in the Los Angeles Times in February 1955, suggested using public funds to build a new stadium in Chavez Ravine to attract a team. No one responded to this suggestion.

The desire for major-league baseball was again demonstrated during spring training in 1955. The Giants and Indians, the 1954 World Series teams, scheduled two games at Wrigley on Saturday and Sunday, March 19th and 20th. In the first game, Willie Mays hit three home runs on consecutive at bats in a 4-2 Giant win before 17,893. Mays’ first shot was over the 345-foot sign in left center, the second was into the right-center field bleachers and the third over the screen in rightfield. The next day 24,434 fans packed Wrigley to see a 7-3 Giant win. Dusty Rhodes slugged a pinch-hit home run, Johnny Antonelli repeated his Game 2 Series win, and Willie Mays made an exceptional running catch in deep center field to retire Al Smith. Los Angeles fans could almost feel like they were at the 1954 World Series. Ticket selling was stopped 30 minutes before game time and at least 2,000 fans were turned away.

At the major-league roster cut down date of March 31, the Chicago Cubs assigned 25-year-old Steve Bilko to Los Angeles. Bilko had been the regular first baseman for the Cardinals in 1953 and had hit 21 home runs but struck out 125 times and hit only .251. He slumped in 1954, was traded to the Cubs. Bilko did not appear able to displace Dee Fondy from the Cubs first base job and the announcement received little fanfare. However, Stout Steve (6′ 1″ and 230 pounds) was destined to rival Jigger Statz as the most popular player in Angel history and dominate the PCL and Wrigley Field for the next three years.

In August 1955, Walter O’Malley announced that the Dodgers would not play at Ebbets Field after 1957. Los Angeles city officials started trying to attract the Dodgers to Los Angeles, visited O’Malley in September, and developed a plan to upgrade Wrigley and condemn buildings to create parking.

The Angels won six of the final eight games from the Stars at Wrigley to tie the season series 14-14. On Wednesday, August 31, 15,485 saw an 8-1 Angel triumph at night. The next evening, Ladies Night, 18,007 witnessed a 3-0 Stars win and the Sunday double header, swept by the Angels 6-5 and 4-3 drew 15,217. Steve Bilko was honored as the Angels MVP between games. The Angels and Stars finished in a tie for third in the PCL and, because there were no playoffs, the teams agreed to play a 5-game series at Wrigley for the City Championship. The anticipation was for high attendance based on the final series that they played. The Stars won the first game 5-2 on September 13 and the second 7-5 with three runs in the ninth inning in a game that took a very unusual 3:26 to play. The Angels came back to win 7-1 and then came from behind to win 4-3 on Jim Fanning‘s eighth inning, two-run home run to tie the series. The Stars won the final game on Sunday 7-6 with six home runs to the Angels none before 11,290. Joe Trimble struck out Steve Bilko with the tying run at third to end the game. Bilko was held homerless for the series.

Total attendance for the five games was a disappointing 36,063 with only the last game exceeding 10,000. Each Star got about $550 and each Angel about $350 and all games were televised. Sid Ziff in the Los Angeles Mirror-News said that the series “demonstrated the need for a new ballpark with ample parking. General admission seats cost $1.25 but residents were charging $1.50 to $3.00 to park on their lawns and driveways. Angel parking is only $0.25 but there is only room for 700 cars.”

On September 15, Steve Bilko was honored as the PCL’s MVP which included a $2,500 cash award. He received an additional $100 for being the home run champion and received the new Tony Lazzeri Memorial Trophy that went to the home run champion. Lazzeri had set the PCL home run record with 60 in 1925 in 197 games. Bilko played in 168 of the Angel’s 172 games, had 204 hits, and led the league with 37 home runs, 356 total bases and 104 strikeouts. Bilko announced that he had signed his 1956 contract and waived his right to be drafted by a major-league team, a move allowed because of the PCL’s open classification.

In the 1955 season, attendance at several PCL cities, particularly Oakland, San Francisco and Sacramento, was disappointing and John Holland, Angel President, announced that they would play all day games in 1956 except for Friday nights. “The competition of free TV entertainment and heavy traffic in the early evening hours makes it inadvisable to play a full arclight schedule.”

One of the greatest middleweight fights of all time was held at Wrigley on May 18, 1956. Sugar Ray Robinson knocked out of Carl (Bobo) Olson with a perfect left hook in 2:51 of the fourth round to retain the middleweight championship before 18,000. The $200,000 gate was a record for California. The fight was nationally televised but blacked out locally.

The Angels dominated the PCL in 1956, winning the pennant by 16 games. Steve Bilko dominated league hitting and flirted with Tony Lazzeri’s PCL home run record. He hit his 46th homer on August 1 which was a pace to hit 63 home runs. However, his homers dropped off over the last six weeks and he finished with 55, missing the Angel club record by one.

On February 21, 1957, the Los Angeles baseball world exploded when the Brooklyn Dodgers announced that they had bought Wrigley Field, the Los Angeles Angels, their territorial rights and Pacific Coast League franchise for $3,000,000 and the Fort Worth franchise of the Texas League. “It is my considered opinion that Los Angeles will have major league baseball by 1960” said Brooklyn president Walter O’Malley.

Only 10 days earlier, O’Malley had given New York officials six months to do something on an acceptable new stadium for the Dodgers. The next day the Dodgers announced that they would schedule some spring training games at Wrigley in 1958. O’Malley had inspected Wrigley Field and other Los Angeles baseball sites in January.

The 1957 season was anti-climatic as the anticipation of major-league baseball permeated the city. This was accentuated after the Giants announced that they were moving to San Francisco. The Angles fared poorly, finishing sixth, and the primary interest was another pursuit by Steve Bilko of Lazzeri’s home run record. Bilko had 39 home runs through August 14 and then went on a home run tear, hitting almost one per game. He hit his 54th home run on September 4 with 14 games to play; a pace to hit 59 home runs. Three days later he hit his 56th to tie the Angel club record; this projected to 60 home runs. However, Bilko did not hit another homer over the last eleven games and 48 at bats.

On September 15, the last PCL games were played in Wrigley with San Diego sweeping a double header from the Angels 9-4 and 5-1 before 6,712. There was a scare during the first game when the club received two anonymous phone reports of a bomb planted in the Angel dugout. The players were moved to the bullpens until the police checked the dugouts. However, the game was not delayed and the crowd was not informed. Pete Mesa of San Diego was the last winning pitcher and Tom Saffell hit the last Angel home run. Bilko was again PCL MVP and led the league with 56 home runs. To illustrate Stout Steve’s versatility, on August 20, Bilko stole home as the lead runner in a double steal, his eighth stolen base of the year.

The long anticipated announcement came on October 8 when the Dodgers announced that they would move to Los Angeles for the 1958 season. A day earlier the L.A. City Council approved the transfer of property in Chavez Ravine to the Dodgers in exchange for the Wrigley Field property. The Dodgers would play in Wrigley Field, the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum or some combination of the two. The Dodgers stated that Wrigley could be enlarged by enclosing the outfield with double decked stands to increase the seating capacity to about 28,000 to 29,000. The center field bleachers would be moved back to Avalon Blvd and a 12-foot screen added to the left field wall. They predicted drawing 1.4 million fans which would exceed the attendance at Ebbets Field for 1956 and 1957.

In late October, the Dodgers said that their primary plan was to plan weekend and holiday games in the Coliseum and weekday night games at Wrigley Field. Enlarging Wrigley to 26,000 to 27,000 was being considered, but only if it cost less than $250,000. In early November, the Coliseum Commission told the Dodgers that they would not modify the stadium for baseball unless the team played at least 35 games there. After a crowd of 102,368 attended the Rams-49ers game on November 10, and because of the large early ticket requests, the Dodgers next said that their preference was to play all their games in the Coliseum and drop Wrigley Field.

However, negotiations with the Coliseum Commission were not going well for the Dodgers; the key issues were cost and the location of home plate. On December 8, O’Malley visited Los Angeles; he toured the Rose Bowl and Wrigley Field and made a new proposal to the Coliseum Commission. Wrigley Field was said to have too few seats, too small a playing area, terrible parking, and poor public transportation, and was located in a declining neighborhood.

After their new proposal to the Coliseum was rejected, on December 18, the Dodgers announced that they were close to finalizing an agreement with the Rose Bowl. O’Malley said that they were going to sell more than 8,000 box seats and there was no way that Wrigley Field could accommodate the crowds. On January 8, 1958, the threat of a law suit by Pasadena residents put the plans for the Rose Bowl on hold. Ford Frick, Baseball Commissioner and a proponent of the Coliseum, called Wrigley a “Cow Pasture and that he didn’t want to see Babe Ruth‘s record of 60 home runs broken there.” He added, “Can you imagine batters like Musial and Mays playing there? They’ll hit the ball into the next county.”

When cost estimates for the Rose Bowl passed $750,000, the Dodgers announced that they were almost certain to play at Wrigley. A new plan would add 2,500 seats in right field and get the capacity to almost 24,000. Los Angeles Mayor Norris Poulson requested the Coliseum Commission make an 11th hour attempt to reach agreement with the Dodgers. On January 17, an agreement was reached with the Coliseum Commission on O’Malley’s fourth proposal of the week. The Dodgers had a two-year agreement and there would be no major- or minor-league baseball at Wrigley Field.

Now owned by the City of Los Angeles, Wrigley Field continued to be used for various sporting events and other functions. On August 18, 1958, Wrigley held its second Heavyweight Championship fight, as Floyd Patterson retained the title when Roy Harris was unable to come out for the 13th round before a crowd of 17,000. On October 16, a team of Dodger major- and minor-leaguers led by Don Zimmer whipped the Los Angeles Eagles, a local Negro All-Star team, 13-1. International soccer moved into Wrigley late in 1958 and the park was used for the city football playoff games. Don Drysdale pitched at Wrigley in a winter league exhibition game and the West team in the annual Pro Bowl practiced at Wrigley for their January 11 game at the Coliseum. In 1959, the television show Home Run Derby began filming at Wrigley Field and was aired for 26 weeks starting in April 1960. Wrigley Field may not have been thriving at the end of the decade but it was being used.

The 1960s — Major League Baseball, Decline and Demolition

In October 1960, the American League announced an expansion from 8 to 10 teams. One of the new franchises was awarded to Gene Autry and Bob Reynolds for Los Angeles and christened the Los Angeles Angels. As part of the agreement the Angels were to play in Wrigley Field for one year and then move to the new Dodger Stadium on a four-year lease with a three-year option.

A franchise was created just four months before opening day. Fred Haney was immediately hired as general manager. He had to hire a staff and a manager, draft players, renovate the stadium, develop a farm system, get office space, sell tickets and interact with the community and baseball establishments. Walter O’Malley was hailed in The Sporting News for advocating a change in the baseball rules that essentially shared his territorial rights with the Angels. The Los Angles press was less kind, criticizing O’Malley for not sharing the Coliseum with the Angels and for forcing an unfair lease arrangement and payments.

Some of the other comments in the press related to the stadium. Bob Hunter of the Examiner predicted that the Angels would draw over 1,000,000 fans. Sid Ziff of the Mirror-News predicted rough sledding with parking conditions that are prehistoric and inadequate, rundown neighborhood, with $75,000 has-beens and discards. George Davis of the Herald Express said that Wrigley with its 20,500 seats should be adequate on all but big days. Mel Durslag of the Examiner called Wrigley “an obsolete concrete shack.” He added that the Angels would draw up to 40,000 in the Coliseum early in the year but later on they would not fill Wrigley.

Al Wolf of the Los Angeles Times said “The AL operates in Los Angeles in 1961 — great — but it’s too hasty for a solid start, even with the fine front-office team of Gene Autry, Bob Reynolds, Fred Haney and Bill Rigney. . . Mob scenes at Wrigley Field, while the nearby Coliseum stands empty, will arouse resentment among those fans who are convinced the Dodgers maneuvered the Angels into that small, parking-less park. “

Del Webb‘s company renovated Wrigley Field which badly needed painting inside and out, refurbishment of the field and the seats, improved restrooms, renovation of the Tower offices and installation of radio and TV booths. The estimated cost was $275,000 and included enlarging the small press box to accommodate at least 80 people. A seat count showed the actual capacity of Wrigley Field to be 20,712, including the bleachers. Ticket prices were $3.50 for box seats, $2.50 for reserved and $1.50 for bleachers on the day of the game.

Angel general manager Fred Haney had managed the Hollywood Stars in the Coast League. He was very familiar with Wrigley and was able to structure the team for the stadium in spite of the inadequate draft procedures in 1961. With players such as Ted Kluszewski, Steve Bilko, Earl Averill, Bob Cerv, Leon Wagner, George Thomas and Lee Thomas, the Angels were built for power, not speed nor defense. Haney also used the draft to get young players such as Dean Chance and Jim Fregosi who would help the Angels for years to come. Five Angels hit 20 or more home runs: Wagner (28), Ken Hunt (25), Lee Thomas (24), Averill (21) and Bilko (20). The Angels were an excellent home team winning 46 of 82 games for a .561 home winning percentage. Of the 14 post-1960 expansion teams, the 1961 Angels were the only one to have a winning home record, finishing 46-36. On the other hand they were a terrible road team winning 24 of 79 games for a .304 road winning percentage.

The characteristics of Wrigley Field that made it a home run hitter’s paradise are somewhat well known. The power alleys were approximately 345 feet from home plate, a very short distance. The distances to the foul poles were respectable, 338.5 feet to right and 340 feet to left. Straight away center field was 412 feet. However the fences were angled toward the infield 9.2 degrees in right and 9.5 degrees in left. Thus, the distance from the plate to the wall actually decreased slightly as you moved away from the foul lines. The minimum distance to the wall was 334.1 feet in right field and 335.4 feet in left. The fence height was 9 feet in right field and 14.5 feet in left field. In addition, there was very little foul territory. It was only 56 feet from home plate to the stands and the stands did not bow away from the field. The foul poles were near the seats. Another unique feature of Wrigley Field was that the light tower in center field was inside the field of play. The tower was screened to the top of the fence and a ball hit off the screening was in play.

The Angels opened the season with a nine-game, 15-day road trip winning only the season opener (13 games were scheduled but there were four rainouts). The first major-league game was played at Wrigley on April 27 with Minnesota beating the Angels 4-2 before a disappointing crowd of 11,931 including ex-Vice President Richard Nixon and Casey Stengel. The first home run was hit by former Los Angeles Jordan High School star Earl Battey. There were opening day ceremonies before the game featuring Ford Frick, Joe Cronin, J. Taylor Spink, Jigger Statz and Ty Cobb. A complete sellout had been forecasted by the team.

The first Angel victory was the next day with a 6-5, 12-inning win over the Twins. The largest major-league crowd at Wrigley, 19,930, saw the Angels beat the Yankees 4-3 on August 22 in spite of Roger Maris‘ 50th home run. This was Maris’ only home run in nine games at Wrigley during his record breaking season. Ken McBride pitched a complete game for his 10th victory. The Angels won their last game played at Wrigley beating Cleveland 11-6 on September 30 for their 70th victory. After the player draft the previous December, writers predicted that the expansion teams would be lucky to win 50 games. On October 1, Cleveland won the final major-league game played at Wrigley Field 8-5 before 9,868. Steve Bilko hit the last home in Wrigley, a pinch-hit smash over the left field wall with two out in the ninth inning.

In the August 2 issue of The Sporting News, Angel President Bob Reynolds said that the club would turn a profit that year. Rent on Wrigley Field was only $150,000 and the radio/TV rights sold for $700,000. He thought that they would draw about 750,000. Reynolds also said that the team was being wooed by more than five communities outside Los Angeles proper and would have their own stadium and identity in five years. The team met this prophesy when they moved to Anaheim for the 1966 season.

Wrigley Field Los Angeles obliterated the record for home runs in a ballpark in one season with 248; 29 more than were hit in Crosley Field in 1957. The home run record lasted until 1996 when the Blake Street Bombers and their opponents hit 271 home runs in the mile-high atmosphere of Coors Field. Three years later, in 1999, the combination of altitude, poor and diluted pitching, and chemically enhanced conditioning pushed the record to 303 home runs at Coors.

The Angels’ season home attendance of 604,422 was very disappointing; their preseason attendance projections exceeded 1,000,000. The Dodgers had predicted an attendance over 1.4 million if they had played in Wrigley in 1958. Starting times were 1:30 PM for all day games, 8:00 PM for night games and 6:00 PM for twi-night double headers. There were no rain outs.

After the Angels departed at the end of the 1961 season for the large, modern confines of Chavez Ravine, Wrigley Field staggered on for another 7½ years. It was used for many minor sports but there were few notable events. On May 26, 1963, a crowd of more than 35,000 jammed Wrigley for a freedom rally where Martin Luther King, Jr. told the audience, “We want to be free whether we’re in Birmingham or Los Angeles.”

August 1965 was a traumatic time for the City of Los Angeles. Civil unrest, in the form of the Watts Riots, broke out southeast of Wrigley Field and spread over much of the south central part of the city. Pressure built up to use the now underutilized Wrigley Field to better serve the community. In July 1966, Wrigley Field was converted to a soccer facility. The first match was between Club Emelec of Ecuador and Guadalajara of Mexico. In January 1967, the Continental League started soccer matches at Wrigley. Wrigley was also used by the California Soccer League in 1967 and for community youth football.

In March 1968, the new Los Angeles Wolves of the North American Soccer League announced that they would train and play exhibition games at Wrigley with league games at the Rose Bowl. After three years of arguing and replanning, the city finally appropriated funding to replace Wrigley Field. In March 1969, Wrigley Field was demolished to create the Gilbert W. Lindsay Community Center including a health center and park.

Summary

Wrigley Field was a Los Angeles treasure. The Wrigley Field clock tower and the LA Coliseum peristyle were the symbols of sports in Los Angeles. For 11 years, two fiercely competitive minor-league teams played in the same park. For 19 more years, they played only a few miles apart. Los Angeles baseball fans strongly identified with these teams and flocked to both Wrigley and Gilmore Fields. A trip across town to Wrigley was a major event to see a game in the finest ballpark west of the Mississippi.

When the Los Angeles Angels were born in 1961, major-league baseball was old hat in Los Angeles. The Dodgers had drawn more than 90,000 to honor Roy Campanella, hosted an All-Star Game, and won a World Series. They were a pennant-contending team with established stars. The Angels had to compete with aging veterans and young ball players with the smallest seating capacity in the majors, limited parking and public transportation in the area had been reduced.

Given the circumstances, the Angels over-achieved on the field, in the front office and at the box office. William K. Wrigley’s “Million Dollar Palace” and the finest minor-league park in the nation hosted professional baseball for 33 years. It had served the city well but its time had passed and it could not be reasonably maintained. It is still fondly remembered by those who attended games there.

Sources

The primary sources for historical information were the Los Angeles Times accessed through ProQuest and The Sporting News accessed through Paper of Record. Statistical information on the 1961 season was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet www.retrosheet.org. Other sources were: Ballparks of Los Angeles, and Some of the History Surrounding Them, by Lauren Ted Zuckerman, 1996; The Angels: Los Angeles Angels in the Pacific Coast League 1919-1957” by Richard E. Beverage, 1981; The Hollywood Stars: Baseball in Movieland 1926-1957, by Richard E. Beverage, 1984; The Spirit of St. Louis: A History of the St. Louis Cardinals and Browns, by Peter Golenbock, 2000; and the SABR Ballparks Committee “Ballparks in the Movies” data base.