Scranton-Dunmore Stadium (Dunmore, PA)

This article was written by Kurt Blumenau

Fourteen seasons. That’s all it took for Scranton-Dunmore Stadium to go from a community’s shiny new plaything to, literally, a pile of parts waiting to be trucked out of town.

Between 1940 and 1953, the people of Scranton, Pennsylvania – and of Dunmore, a small neighboring community – got to see Ted Williams, Satchel Paige, and farmhands from three major-league franchises take the field. They saw several minor-league championship teams, as well as community events ranging from Catholic Masses to mock bombing raids. Scranton-Dunmore Stadium wasn’t around for a long time . . . but it was certainly around for an eventful time.

Decades before brownfield redevelopment became a widely discussed concept, Scranton-Dunmore Stadium was built on the former site of a manufacturing plant.1 The Scranton Stove Works, maker of cooking and heating stoves, had built several structures on property on Monroe Avenue in Dunmore, near Jefferson Avenue and New York Street, adjacent to the Scranton city line. However, the Stove Works moved its operations elsewhere in 1931, leaving the old buildings vacant. On the windy night of July 28, 1936, a massive fire of unknown origin destroyed the former Stove Works buildings and threatened a nearby building belonging to United Gilsonite Laboratories – a name that will recur in this story.2

Scranton’s history in pro baseball went back to the 1886 Scranton Indians of the Pennsylvania State Association. For most of the intervening years, Scranton teams had entertained fans at a facility called Athletic Park, on Providence Road in the city proper. But in 1939, Athletic Park owner Jim Sweeney refused to make improvements demanded by the team, including the construction of a new grandstand and bleachers. A local news column noted that the team owners had “lost a fortune through lack of accommodations last summer,” adding that fans at Athletic Park had put up with “disruptions and inconveniences.”3 (At least the fans got to watch winning baseball for their trouble: The 1939 Scranton Red Sox won both the regular-season and post-season playoff championships of the Class A Eastern League.4 They also set a league attendance record with well over 310,000 fans.5)

Rumors of a new facility in neighboring Dunmore emerged in December 1939 and were confirmed just a week or two later. On January 4, 1940, the Scranton Times not only reported the formal announcement of a new stadium on the Stove Works site but also printed a rough outline of the park’s planned layout. The stadium was to have a roofed grandstand from first base to third, with separate bleacher sections down each foul line. The park’s dimensions were sketched out at 350 feet down each foul line, 370 feet to the alleys, and 375 feet to straightaway center. The entire plant was expected to cost $150,000 and, audaciously, was anticipated to be ready for Opening Day in late April.6 With the United States still almost two years away from entering World War II, the immediate availability of structural metal and other materials – not to mention skilled construction workers – would not be an issue.7

Ground was broken in a brief ceremony on February 6.8 As of March 15, workers were reported to be “feverishly at labor rushing grading, tearing away hills, dumping hundreds of tons of topsoil and many more items of work necessary for a present-day modern baseball field.” Gardeners, plumbers, fence builders, and other craftsmen were “ready to sail into action.”9 One wonders if iron workers Thomas Snodgrass and Russell Miller were rushing feverishly on April 19, 1940, when a scaffold broke beneath them, and they fell 40 feet. Snodgrass suffered a possible fractured skull and broken leg, Miller a possible broken knee.10

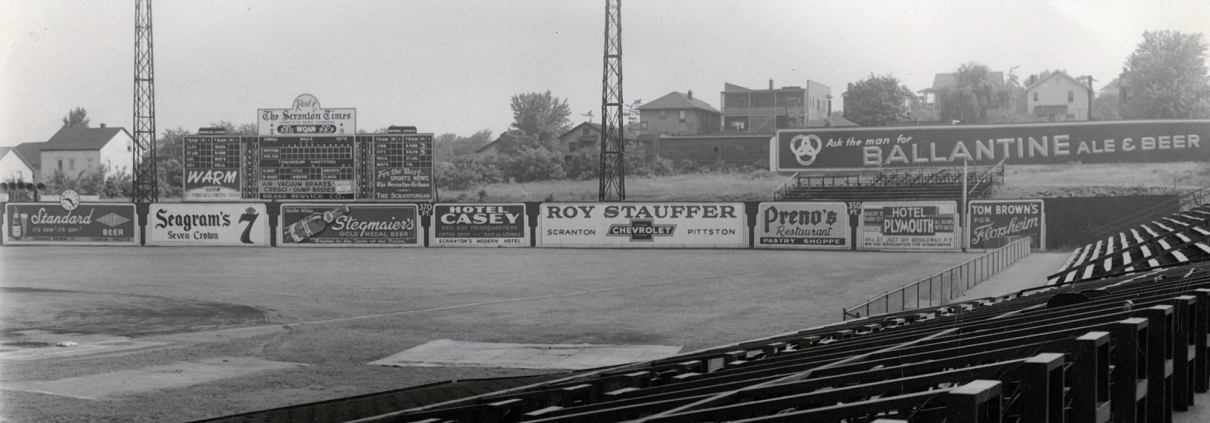

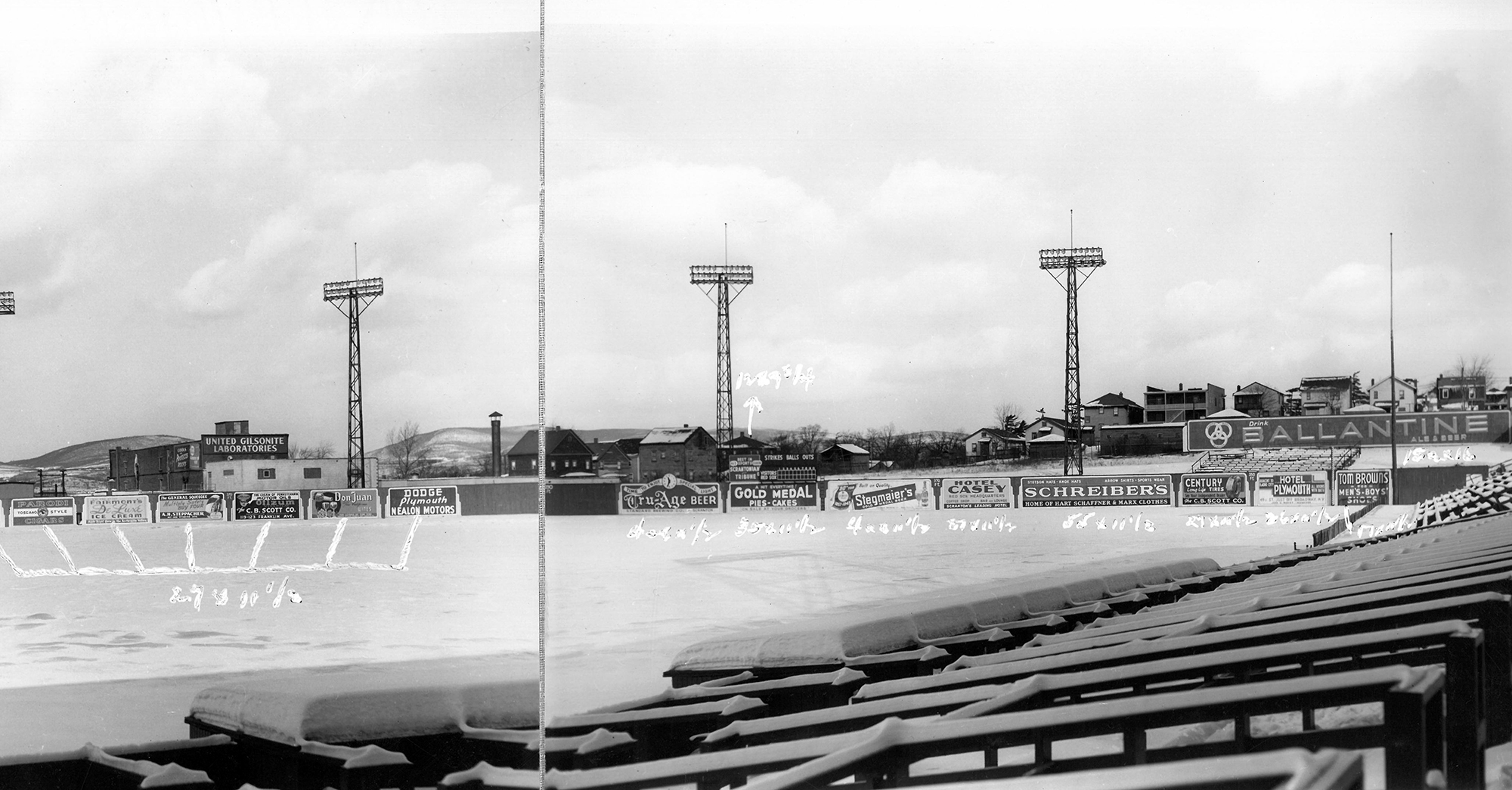

As construction proceeded, most of what was projected in January came to pass. The finished stadium had a covered, single-decked grandstand flanked with bleacher sections, with a reported capacity of 13,500.11 The construction cost remained, in stories over the years, at no more than $150,000.12 The park’s playing dimensions were close to what was initially described, varying only slightly in the retelling. A 1959 news story recalled them as 350 feet down the lines and 390 to center,13 while a 1981 retrospective described them as 350 feet down the lines, 390 feet to the power alleys and 375 to center.14 By any recollection, a home run was not an easy poke. An April 1946 story about Scranton players seeing the park for the first time quoted one as saying, “That outfield sure gives a fellow plenty of room to move around.”15 And a 1952 story referred to Scranton-Dunmore Stadium as “the Eastern League’s most spacious park.”16

The story announcing the park in January 1940 did not mention lighting, and an advertisement just before the park’s opening indicated that lighting was not fully in place.17 However, the stadium gained lights very early on. As early as September 1941, night high school football games were advertised18 while an ad for a baseball game with an 8:25 P.M. start appeared in May 1942.19 The latter advertisement also promoted announcer Claude Haring, a holdover from Athletic Park days, calling the action over radio station WARM. Haring later announced games for the Philadelphia Phillies, Philadelphia A’s, and Pittsburgh Pirates.20

The one thing the builders couldn’t do was to complete the stadium by Opening Day, April 25.21 They didn’t miss by much, though. A planned May 4 opening was pushed back by rain, but Scranton-Dunmore Stadium opened in grand fashion the following day with a doubleheader against the northeast Pennsylvania rival Wilkes-Barre Barons. An estimated 18,000 fans filled the park beyond capacity, with fans standing 10 to 20 deep in the outfield and packing the area behind the grandstand. The crowd was so great that it “made it all but impossible for the games to get under way,” one article reported, and as many as 3,000 more fans were turned away.22

Two fans received special notice in the Opening Day coverage. One, identified only as “Hi-Yo Silver,” turned handsprings and was introduced to the crowd by a special guest – Eastern League president Tommy Richardson.23 The other, identified as “dusky Gus Buchanan and his trusty megaphone,” was a Black whitewash contractor and former professional guitarist known for his high-volume support for Scranton teams.24 He had also managed a local Black baseball team called the Scranton Colored Giants, though it appears the team dissolved before the construction of Scranton-Dunmore Stadium and never played there.25

The doubleheader set a new attendance record for Scranton and the Eastern League and outdrew five major-league games held that day.26 Scranton won the first game 13-7, while Wilkes-Barre won the shortened six-inning nightcap, 6-2. The fans on the field played a major role in the game: News coverage reported “a flock of two-base hits” as balls that might ordinarily have been caught or fielded landed in the overflow crowd. (Box scores list 14 doubles in the first game and six in the second, though it’s not specified how many were of the ground-rule variety.) Reports also noted that Wilkes-Barre center fielder Nick Tremark went into the crowd in the second game in pursuit of a fly ball and emerged with a broken nose.27 Wilkes-Barre was a Cleveland Indians farm team, and two future Cleveland mainstays appeared in both halves of the opening doubleheader. Future Hall of Famer Bob Lemon, not yet converted to pitching, played right field, while Jim Hegan caught. Both were 19 years old.

The name Scranton-Dunmore Stadium seems to have caught on gradually and informally. Opening Day coverage in the Scranton Tribune referred to the park as “Scranton’s new stadium,” while the rival Scranton Times called it “the new Scranton Stadium.” The more descriptive “Scranton-Dunmore Stadium” began appearing in news accounts later in the month, although the park continued to be called “Scranton Stadium” or “Dunmore Stadium” in various uses.28

The name of the home ballclub was also fluid for most of the park’s existence. Scranton teams in several sports had been called the Miners for many years in recognition of the region’s coal-mining heritage. During the team’s Boston affiliation, news accounts used both the Miners and Red Sox names in describing the team, as well as variants like Red Sockers.29 During the team’s hookups with the St. Louis Browns and Washington Senators in 1952 and 1953, the Miners name was used exclusively.

Like most minor-league parks, Scranton-Dunmore Stadium also hosted other community events. Bishop William J. Hafey of the Diocese of Scranton celebrated Mass at the stadium as part of the city’s diamond jubilee celebration in July 1941.30 The same day, Protestant and Jewish residents joined for a union vesper service described as “probably unprecedented in the religious life of Scranton.”31

Two years later, the brotherhood of man was replaced by man’s inhumanity to man, as the US Army used the stadium to stage a demonstration of air raids on civilian targets. Army planes bombed specially built structures set up in center field. One advertisement proclaimed, “See What Happens When Fire Bombs Fall on a City!,” and nearly 8,000 people turned out to watch.32 (The event, free to attend, was intended to spur sales of war bonds.)33

Youth baseball teams played at the stadium, and some players used it as a springboard to the pro game, such as Frank Santorsa. Santorsa signed with the Boston Braves’ organization straight out of Dunmore High School and played three years in the low minors between 1948 and 1950. Before that, he gained local renown as the first schoolboy player – by some accounts, the only one – to hit a home run at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium. This accomplishment was sufficiently noteworthy to be mentioned, some 56 years later, in his obituary.34

High school and college football games were common as well. Professional football, not yet the nation’s most popular sport, came to town in August 1946 when the Pittsburgh Steelers played an exhibition against a local team, the Scranton Miners, before 7,487 fans. Led by future Pro Football Hall of Famer Bill Dudley, the Steelers put up 37 points in the first quarter and cruised to a 47-0 win. They posted a 5-5-1 record in the regular season.35

Scrantonians saw an even more dominant performance in August 1950, when middleweight champion boxer Sugar Ray Robinson fought challenger José Basora before a crowd of 4,145 at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium. The fight lasted less than a minute, and Basora never threw a punch. A flurry of fists from Robinson dropped the challenger three times, the last time for a 10-count. Many of the paying customers, expecting more entertainment for their money, booed Robinson.36

But back to baseball. Scranton and the Red Sox stayed partners throughout the 1940s, and the minor-league club did well on the field for most of that period. Manager Nemo Leibold’s 1942 squad trailed Albany in the regular season by only one game, staying close with “brilliant pitching, great defensive play and a determination to win every minute in every game.”37 Scranton then swept Wilkes-Barre and defeated Binghamton, four games to one, to win the league playoffs.38

In 1946, the Scranton team won the regular-season title with a 96-43 record – 18½ games in front of second-place Albany – and then knocked off Wilkes-Barre and Hartford for the playoff championship. They did the same in 1948, except this time they finished only three games ahead of Albany. They made the playoffs in 1947 and 1949 before toppling to the cellar in 1950. In a last hurrah, the Scrantonians bounced back for a second-place regular-season finish and a final playoff championship in 1951.39

Noteworthy players from the 1940s included locally raised pitcher Harry “Fritz” Dorish, 12-8 with a 2.07 ERA in 1942; pitcher Al Widmar, 10-5 in 1943, who met his wife during a rain delay at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium;40 future big-league infielder and manager Sam Mele, a .342 hitter in 1946; pitcher Mel Parnell, 13-4 and 1.30 that same year; outfielder Jim Piersall, a .281 hitter in 1948; third baseman and future Boston icon Frank Malzone; and pitcher Joe Wood, son of Hall of Famer “Smoky Joe” Wood. In August 1941, the younger Wood threw a no-hitter for Scranton with his father watching.41

Beefy first baseman Walt Dropo hit 12 homers in 87 games for Scranton in 1947, three seasons before he became the American League Rookie of the Year with the Boston Red Sox. Dropo also linked his name with a local landmark, the United Gilsonite building.42 Having survived the big 1936 fire, it served as a highly visible landmark beyond the center-field fence.43 Dropo earned local fame for occasionally parking baseballs on its roof.44 Also in 1947, on September 4, fans at the stadium paid tribute to a visiting player – pitcher Junior Walsh of the Albany Senators, who had grown up in Dunmore and graduated from Dunmore High School.45 Walsh played parts of five seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Dropo returned to Scranton-Dunmore Stadium in June 1950, in the company of Ted Williams and other Red Sox teammates, as the Boston parent club played an exhibition against their Scranton farmhands in front of 9,342 fans. Dropo hit one of three home runs in the game as Boston won 9-3. Williams and Dropo also took part in a pregame home-run derby, but were outdone by their lighter-hitting colleagues Bobby Doerr and Al Zarilla. Doerr and Zarilla tied for the win with two homers apiece – more proof, perhaps, that the ballpark was no place for easy home runs.46

The Red Sox also received one other crucial export from Dunmore, though he wouldn’t arrive in Boston for many years. Dunmore native Joe Mooney got his start on the Scranton-Dunmore Stadium grounds crew, learning the trade from head groundskeeper Denny Baskerville.47 After years in the minors, Mooney became the Washington Senators’ groundskeeper in December 1960.48 A decade later he moved to Fenway Park, reportedly on Williams’ recommendation, and stayed there for more than 30 years.49

However, the Red Sox parted ways with Scranton in 1951 after three unprofitable seasons.50 Lou Baselice, a New York businessman and baseball fan with interests in northeast Pennsylvania, paid the Red Sox an estimated $102,500 for the team and the stadium.51 The moribund St. Louis Browns, just two seasons away from moving to Baltimore, linked up with Scranton in 1952. This one-year hookup provided Scranton a non-competitive and unprofitable team that finished 66-73, 17½ games back. Former Negro Leaguer and future Hall of Famer Leon Day went 13-9 for Scranton at age 35, while future Yankees relief pitcher Ryne Duren went 0-5 at age 23.

Scranton-Dunmore Stadium got another big-league visit out of the St. Louis connection, as the parent Browns beat the minor Miners 4-1 in front of 4,864 fans on June 5, 1952. Notable visitors included two future Hall of Famers in Browns manager Rogers Hornsby and pitcher Paige, who pinch-hit an infield single and came around to score the Browns’ final run.52

In 1953, following a tumultuous offseason, Scranton adopted a community ownership model for its team, with Baselice continuing to own the stadium.53 The team signed a partial affiliation with the Washington Senators,54 another franchise whose years of mediocrity eventually ended in a move. A combination of Senators farmhands and locally sourced players went 51-100 under manager Morrie Adenholt, finishing 51½ games out of first place.

Attendance in 1953 plummeted to 62,266, or about 825 fans a game. The Scranton Times pointed out that two promotional nights had accounted for almost 21 percent of the season’s fans.55 The team had reportedly needed to draw 100,000 fans for the season, or 1,500 per game, to turn a profit. In 1940, its first year at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium, the team drew 232,226 fans – second-best in league history to that time – and in 1946 it drew 212,859, third-best in league history up to then.56 In 1949, the first of the team’s unprofitable final years, it drew 131,875 fans.57 (Children got in for free on Knothole Days a few times each season, but as one local scribe wrote years later, “If you knew where the loose boards in the fence were, every game could be Knothole Day.”58)

At the end of the 1953 season, the Scranton baseball operation was $35,000 in debt – money that would need to be repaid by any prospective owner wishing to operate a future team in the city.59 Scranton tried unsuccessfully to reconnect with a major-league franchise that would pay at least some of that debt and restore financial stability.60 The team also tried to stay afloat by selling up to 10 players to pay off its debts – but no takers stepped up. In December 1953, the Scranton franchise was returned to the Eastern League. It was replaced the following season by a team playing in Allentown, about an hour south.61

The last pro baseball game at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium took place on September 7, 1953. Scranton and Wilkes-Barre played a home-and-home doubleheader, with Scranton hosting the first game. With 835 fans in attendance, the Scrantonians claimed a 4-0 win behind the shutout pitching of Edgar Moeller.62 Although it stayed standing for roughly another year, the stadium’s existence ended for most purposes at 3:43 P.M. that day, when Scranton right fielder Vince Fucci gathered in a game-ending fly ball off the bat of Wilkes-Barre’s Pete Caniglia.63

What happened to Scranton’s passion for pro baseball? Many in the community blamed television, a new and convenient source for major-league baseball and all manner of other entertainment. The hookups with the Browns and Senators, unsuccessful and unsatisfying on the field, didn’t help. One sportswriter blamed the disappearance of “fierce civic pride” from the local scene, adding, “It adds up to a lack of patronage for the ‘home team.’ ”64

The same woes that ailed Scranton hit many other communities at the same time. In 1949, 59 leagues operated in 432 towns and cities, drawing 41 million fans. In 1952, those numbers had dropped to 38 leagues in 287 towns and cities, drawing 26 million fans.65 (Neighboring Wilkes-Barre lost its pro team a year later. Allentown lost affiliated minor-league baseball after the 1960 season and didn’t get it back until 2008.66)

The losses on the field in 1953 were compounded by two losses off the field that bookended the season. On April 26, 71-year-old fan William Sipple suffered a heart attack while watching a game at the ballpark; he died a week later.67 And on September 24, Dunmore Police Patrolman Lawrence Gaughan died at 50. He’d been the head of the police detail at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium, as well as a former schoolboy athlete in the area, and was fondly remembered. “It will be a bit lonesome covering future sports assignments at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium with Lawrence A. Gaughan . . . missing from the baseball park,” Joe M. Butler of the Scranton Times wrote.68

Butler apparently did not realize that there would be no future sports assignments – or very few – at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium. That possibility quickly began to emerge, though. In November 1953, Baselice let slip that he’d been approached by several parties interested in using the property for “industrial purposes.”69 In January 1954, the Scranton Times ran a plaintive letter purporting to be from the stadium, which said in part: “Am I going to be dismantled and is some big, ugly building going to take my place, stand on this special ground?”70 Meanwhile, the Dunmore Rotary Club tried to muster enough money in the community to buy and preserve the stadium. The University of Scranton was also rumored to be interested at the right price.71

By the start of summer, that dream was dead. A news story in early June reported that the Green Ridge Junior League, a new loop of four teams of 13- to 15-year-olds, had Baselice’s permission to use the stadium three nights a week “until such time as dismantling of the park might interfere.”72 An all-star game between Green Ridge and another youth league, played on August 28, 1954, appears to have been the last sporting event at Scranton-Dunmore Stadium; no further events are mentioned in area newspapers.73

Work to break down the ballpark was underway in October 1954.74 Seats, the scoreboard, and other useful components were sold a few months later to interests in Richmond, Virginia.75 Almost 25 years later, the scoreboard and seating from Scranton-Dunmore Stadium were reportedly still in use there.76 One landmark that lingered near the site of Scranton-Dunmore Stadium was a sign for a local business, Foderaro Keys, that was visible beyond right field. As of 1967, the sign was still there but fading fast.77

The ballpark’s disappearance baffled some who remembered its glory days, such as Mike Lynn. As a boy in the Scranton area, he sneaked into Red Sox games at the stadium and also watched the Robinson-Basora massacre, before his family moved to New Jersey. In the summer of 1977, he made his first visit to Scranton since moving out and was astonished to find no trace of his childhood ballpark. By that time, Lynn had developed his own career in pro sports: He was the general manager and vice president of the Minnesota Vikings of the National Football League.78

By April 1955, the stadium’s vacant lot was a community nuisance – a lovers’ lane whose most brazen participants parked directly in front of neighboring homes.79 But development was coming, and by the beginning of August, the site was home to an A&P grocery store.80 The property has remained a retail development ever since, with subsequent tenants including Food Fair and Price Chopper. As the Red Sox reached the World Series in October 1975, a newspaper editorial pointed out that a checkout lane stood at the former site of home plate. The editorial also mentioned that the Scranton Red Sox used to draw 10,000 fans per game, asking, “One wonders what it would take today to attract 10,000 paying fans to an athletic contest in the Scranton area?”81

The residents of Scranton and Dunmore eventually found out, although they had to wait 36 years. Minor-league baseball returned to northeast Pennsylvania in 1989 in the form of the Scranton/Wilkes-Barre Red Barons, a Philadelphia Phillies affiliate playing in a brand-new stadium in the Triple-A International League. As of 2022, Scranton and Wilkes-Barre – formerly rivals with separate teams – continued to jointly hold a Triple-A team.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Howard Rosenberg and fact-checked by members of the SABR Bio-Project fact-checking committee.

Sources

The author consulted baseball-reference.com and retrosheet.org for background information on players, teams, and seasons. He also relied on historical news stories in addition to those specifically cited, mainly from newspapers in Scranton and Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.

Photo credit

All photos are courtesy of Nick Petula and the Lackawanna Historical Society.

Notes

1 In planning and development jargon, a “brownfield” is a site that has previously been developed for industrial or commercial use and is now available for reuse – as opposed to a “greenfield,” a site not previously built on. Contamination from previous development is frequently an issue in brownfield redevelopment, although it was not recorded as a concern in the construction of Scranton-Dunmore Stadium.

2 Edward J. Gerrity, “This Is My Town,” Scranton Times-Tribune, March 1, 1970: B5.

3 “Touching All the Sacks,” The Scrantonian (Scranton, Pennsylvania), December 24, 1939: 26; Chic Feldman, “Hatchin’ ‘Em Out,” Scranton Tribune, December 21, 1939: 20.

4 “Owners of Ball Team to Have Park in Dunmore; Plan to Spend Huge Sum,” Scranton Times, January 4, 1940: 20. The 1939 Scranton team, managed by Nemo Leibold, included future Boston Red Sox pitchers Mickey Harris and Tex Hughson. Eddie Popowski, the team’s starting second baseman, never made the majors as a player but had a long career in the Red Sox organization as a major- and minor-league manager and coach.

5 Some sources set Scranton’s 1939 attendance at 311,000. A figure of 317,249 is given in Jimmy Calpin, “Lookin’ ‘Em Over,” Scranton Times, April 27, 1953: 18.

6 “Owners of Ball Team to Have Park in Dunmore; Plan to Spend Huge Sum.”

7 In the 21st century, municipal planning review of such a project could be expected to take at least four months. Dunmore did not create a Planning Commission and Zoning Board until the fall of 1958, so the organizations that would lead such a review today didn’t exist in 1940. “Organization Held,” Scranton Tribune, October 23, 1958: 12.

8 “Ground Breaking Program at New Ball Park Today,” Scranton Times, February 6, 1940: 19.

9 Photo caption, “Panoramic View of New Baseball Park in Dunmore,” Scranton Times, March 15, 1940: 32.

10 “Two Workers Fall 40 Feet,” Scranton Tribune, April 20, 1940: 3. Snodgrass, the more severely injured of the pair, survived the incident. He died July 8, 1979, according to an obituary in the following day’s Scranton Times.

11 While a few stories printed after the park’s demise set its capacity at about 10,000, a majority of sources list 13,500. “Stadium Cost $150,000,” a short news item on page 38 of the Scrantonian of September 26, 1943, may be most trustworthy, as it was printed during the stadium’s existence, only three years after it opened. Coverage of the park’s opening day also mentions the 13,500 figure.

12 Lance Evans, “With The Minor Leagues, If You Don’t Promote, You’re Dead,” Scranton Times, July 8, 1981: 17, used a figure of “less than $150,000” for the park’s cost; Bill Savage, “Stadium Opening Was Big Hit in ’40,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, May 1, 1988: 9D, quoted a figure of $125,000. An online inflation calculator provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics indicated that $150,000 in January 1940 was roughly akin to $3.3 million in January 2022.

13 Jimmy Calpin, “Lookin’ ‘Em Over,” Scranton Tribune, June 1, 1959: 12.

14 Evans, “With The Minor Leagues, If You Don’t Promote, You’re Dead.” These dimensions (350-390-375-390-350) may be the most accurate; a game story from 1942 mentions a home run hit 380 feet to center field; “Sox Win Three from Barons Over Weekend – State Pin Show,” Scranton Times, May 4, 1942: 16.

15 Chic Feldman, “Long Fences, Homes Interest Miners Most,” Scranton Tribune, April 30, 1946: 14. The player quoted was outfielder William Thomas “Tom” West, who played five minor-league seasons between 1944 and 1948.

16 Chic Feldman, “Crawford’s 26th Ensures Barnes’ 3 to 0 Conquest of Chiefs,” Scranton Tribune, August 6, 1952: 15.

17 Full-page advertisement taken by the Dunmore, Pennsylvania, business community, Scranton Times, May 3, 1940: 21. Light stanchions are visible in the photo included in this advertisement, but the language indicates that lighting had not yet been installed.

18 Game advertisement, Scranton Tribune, September 26, 1941: 22.

19 Game advertisement, Scranton Tribune, May 19, 1942: 14.

20 Associated Press, “Radio Announcer Fatally Stricken,” Gettysburg (Pennsylvania) Times, October 18, 1967: 4.

21 “Brown Holds Triplets to Five Singles,” Wilkes-Barre Times-Leader, April 25, 1940: 25.

22 “Record Crowd Sees Red Sox Split Pair,” Scranton Times, May 6, 1940: 20.

23 “Record Crowd Sees Red Sox Split Pair.”

24 “Gus Buchanan Parked Guitar when He Discovered Baseball,” The Scrantonian, June 22, 1947: 40.

25 “Gus Buchanan, 80, Sports Figure, Dies,” Scranton Times, June 11, 1960: 14. A Newspapers.com search for “Scranton Colored Giants,” conducted on February 17, 2022, found that the most recent reference to a Scranton Colored Giants game in the site’s database was in August 1933.

26 The Scranton Times said four in “Record Crowd Sees Red Sox Split Pair,” but the reported crowd of 18,000 in Scranton was actually larger than those at five big-league games on the same day. Those games were: Philadelphia Phillies at Chicago Cubs, listed attendance 14,676; Boston Bees at Pittsburgh Pirates, 10,992; Brooklyn Dodgers at St. Louis Cardinals, 13,119; Chicago White Sox at Philadelphia A’s, 16,174; and St. Louis Browns at Washington Senators, 14,000.

27 “Record Crowd Sees Red Sox Split Pair.”

28 A Newspapers.com search for the phrase “Scranton-Dunmore Stadium” indicates that it first appeared in print on May 11, 1940, in an advertisement placed by the Scranton Transit Co. in the Scranton Tribune. The transit company took the ad to promote its bus service to and from the ballpark.

29 Author’s research. Variable names used in the Red Sox era are also noted in Lance Evans, “Area Baseball Fans Wistfully Recall Thrills of Seasons Past,” Scranton Times, July 7, 1981: 13.

30 “Centennial Events Today and Tomorrow,” Scrantonian, July 27, 1941: 1.

31 “Three Religious Ceremonies Are Features on Centennial Sunday; Two Are Held in Stadium,” Scranton Times, July 28, 1941: 3.

32 “Air Havoc Simulated at Stadium Exhibition,” Scranton Tribune, October 9, 1943: 3.

33 Event advertisement, Scranton Tribune, October 8, 1943: 17.

34 “Frank A. Santorsa Sr.,” Scranton Times, January 13, 2003: 16. One of several earlier references to Santorsa’s feat can be found in “Dishin’ The Dirt,” The Scrantonian, February 4, 1973: 53.

35 “Steelers Route Miners, 47-0 – Cards and Flock Still Tied,” Scranton Times, August 24, 1946: 10.

36 “Robinson’s One-Minute Kayo of Basora Booed at Stadium,” Scranton Times, August 26, 1950: 12.

37 Joe M. Butler, “Hats Off to the Red Sockers, Governor’s Cup Champs,” Scranton Times, September 21, 1942: 14.

38 Joe M. Butler, “Scranton Ends Trips’ Series in Five Games,” Scranton Times, September 21, 1942: 15.

39 Most of the results in this paragraph are taken from baseball-reference.com. Information on 1951 playoff championship, which is not shown on baseball-reference.com, taken from United Press, “Scranton Cops E.L. Playoffs,” Shenandoah (Pennsylvania) Evening Herald, September 22, 1951: 8.

40 Larry Holeva, “Widmar ‘Valued Arm’ with Blue Jays’ Pitchers,” Scranton Times, October 24, 1993: C8.

41 “Wood’s No-Hitter Elevates Red Sox into Fourth Position,” Scranton Times, August 8, 1941: 18. Pitching in relief, Wood also earned the win in the fifth and clinching game of the 1942 playoffs.

42 As of early 2022, United Gilsonite Laboratories was still in operation in Dunmore. The company makes specialty paints and coatings.

43 A good picture of the stadium as it existed in its final season, with the United Gilsonite building visible in the distance, can be seen on page 45 of the April 19, 1953, edition of The Scrantonian.

44 Jimmy Calpin, “Lookin’ ‘Em Over,” Scranton Tribune, January 6, 1981: 16. Calpin also mentioned this in his “Lookin’ ‘Em Over” sports column of June 1, 1959.

45 “James ‘Junior’ Walsh, Ex-Major Leaguer, Dies,” Scranton Tribune, November 13, 1990: A7. Walsh was born in New Jersey but moved to Dunmore at a young age.

46 Jimmy Calpin, “Red Sox Outslug Scranton Before 9,342 Fans, 9 to 3,” Scranton Tribune, July 13, 1950: 17.

47 A photo of Mooney and Baskerville can be seen in The Scrantonian, August 17, 1975: 60.

48 Guy Valvano, “Baseball Hall of Fame ‘Picks’ Mooney 2nd Time,” The Scrantonian, August 17, 1975: 60.

49 Jon Couture, “Joe Mooney, Red Sox Hall of Fame Groundskeeper for Three Decades,” Boston Globe, December 7, 2020: D5.

50 Jimmy Calpin, “Lookin’ ‘Em Over,” Scranton Times, April 27, 1953: 18. In another of his “Lookin’ ‘Em Over” columns – this one on December 23, 1952 – Calpin wrote that the 1951 team was a success on the field, but “failed to attract attention and finished so far in the red the Bosox pulled out, sold the stadium and moved their players to Albany.”

51 “Baselice Closes Scranton Deal; No Farm Agreement Is Secured,” Scranton Times, November 13, 1951: 29. News coverage from the period described Baselice as a former professional pitcher who reached the Triple-A level. Baseball-reference.com has no listing matching his name.

52 Chic Feldman, “Brownies Hustling Hit Amid 4-1 Party,” Scranton Tribune, June 6, 1952: 21.

53 “Casey Heads Baseball Club; Scrantonian Donates $250,” The Scrantonian, March 15, 1953: 41.

54 “Pro Owners Must Decide Fate of Franchise Today,” Scranton Times, December 15, 1953: 31.

55 “Scranton Wins 4-0, 10-4 in Labor Day Encounters,” Scranton Times, September 8, 1953: 22.

56 The 212,859 attendance figure for 1946 has been cited by Scranton newspapers in numerous stories over the ensuing decades. The third edition of the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, 2007) lists Scranton’s attendance that year as only 181,302 – still the most in the league that season.

57 Jimmy Calpin, “Lookin’ ‘Em Over,” Scranton Times, April 27, 1953: 18.

58 C. Brendan Gibbons, “Days When Scranton Miners Played in Dunmore Recalled,” The Scrantonian, July 2, 1967: 28.

59 “Pro Owners Must Decide Fate of Franchise Today.”

60 “Pro Owners Must Decide Fate of Franchise Today.”

61 United Press, “Scranton Gives Up Franchise to Eastern League,” Scranton Tribune, December 16, 1953: 18.

62 Moeller pitched in parts of eight minor-league seasons between 1947 and 1957. His career peaked with a few appearances at Triple-A.

63 “Scranton Wins 4-0, 10-4 in Labor Day Encounters.” Scranton Elks’ Night on July 13 reportedly drew 4,822 fans, while Auto Night on August 18 attracted 8,222 attendees.

64 Chic Feldman, “Tuesday D (Dark) Day for Scranton,” The Scrantonian, December 13, 1953: 34.

65 Dave Diles (Associated Press), “Trautman Discusses Plight of Minor League Baseball,” Scranton Times, September 15, 1953: 22.

66 Allentown was home to an independent league team, the Ambassadors, from 1997 through 2003.

67 “William H. Sipple of Taylor Dead,” Scranton Tribune, May 4, 1953: 10. The obituary mistakenly gives the date of Sipple’s heart attack as May 26. News stories from April 27, 1953, mention that Sipple suffered “a paralytic stroke” while watching that day’s Scranton-Schenectady game. Schenectady won a scheduled first game, 10-3, and was one out away from completing five innings of the second game with a lead when the umpire called a halt to the action.

68 Joe M. Butler, “The Sportscope,” Scranton Times, September 25, 1953: 34.

69 “Miners’ Directors Set for New York Discussion,” Scranton Times, November 20, 1953: 35.

70 “Stadium Soliloquy,” Scranton Times, January 2, 1954: 6. One can only wonder who wrote and submitted this letter. It’s interesting that the letter uses the word “dismantled” – a precise term, and exactly what ended up happening to the ballpark – as opposed to “destroyed,” “torn down,” “razed,” or another more generic term.

71 “Dunmore Rotarians Map Plans for Stadium-Saving Movement,” Scranton Times, February 9, 1954: 55.

72 “Green Ridge Loop Opener Tonight,” Scranton Times, June 3, 1954: 33.

73 “Little Leagues,” Scranton Tribune, August 30, 1954: 13.

74 “Ingram Firm Orders Work Stoppage, Scotches Rumors of Team Returning,” Scranton Times, October 15, 1954: 31.

75 Jimmy Calpin, “Scranton Baseball Stadium Purchased by Richmond Group,” Scranton Tribune, December 7, 1954: 17. Calpin’s story specified that Baselice continued to own the stadium property.

76 “Dishin’ the Dirt,” Scrantonian, August 13, 1978: 51.

77 Gibbons.

78 “City Native Mike Lynn Dons 3 Hats with Vikes,” Scranton Tribune, December 30, 1977: 11A.

79 Harold B. Luthner, “Better Lighting Seen as Remedy at Parking Lot,” The Scrantonian, April 3, 1955: 8.

80 “Attended Opening,” Hazleton (Pennsylvania) Plain Speaker, August 3, 1955: 20.

81 “Welcome Intrusion,” Scranton Times, October 17, 1975: 4.