Roy Castleton

When he pitched a hitless inning in relief for the New York Highlanders (already beginning to be called the Yankees) on April 16, 1907, Roy Castleton became the first native of Utah to play major league baseball. Castleton, however, was much more than the answer to a trivia question. He was a promising left-handed pitcher with a minor league perfect game to his credit.

When he pitched a hitless inning in relief for the New York Highlanders (already beginning to be called the Yankees) on April 16, 1907, Roy Castleton became the first native of Utah to play major league baseball. Castleton, however, was much more than the answer to a trivia question. He was a promising left-handed pitcher with a minor league perfect game to his credit.

The story of the Castleton family is the story of Utah’s settlement. Between 1860 and 1870, over 9,000 persons emigrated from England to Utah. One of those families was the Castletons. The family had lived in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, since at least the mid-eighteenth century. James Joseph Castleton was born there in 1829, the eldest of ten children, and worked as a fisherman as well as a rope and twine maker. On January 2, 1854, he married Frances Sarah Brown, from the nearby village of Pulham. On October 4 of that year, their first son, Charles, was born.

During the 1850s, the Mormon Church wanted to expand and develop their Utah colony. Much of their effort was concentrated on gaining converts in Europe, with a particular emphasis on the British Isles. At least one member of the Castleton family, Frances, was among those converts. The church established the Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, which helped more than a third of church members emigrating from Europe to the American West.

In early 1863, James Castleton, his wife and four sons were among the immigrants. They left London on the Amazon around the beginning of June. They reached the Port of New York on July 20. The family traveled by train to Omaha, Nebraska, then secured teams of oxen and set out across the plains, reaching the Salt Lake Valley on October 4. Frances was pregnant at the time and rode while those able, including Charles, walked much of the way across the West.

James Castleton was hired by Brigham Young as a gardener, and was still at that job in 1870. He saved enough money to buy land at L Street and Seventh Avenue and open a store.

Charles Castleton worked at the store, and became a carpenter. In 1879 he married Mary Ann Luff, also an immigrant from England. Charles and Mary Ann would have seven children. On July 26, 1885, a son, Royal Eugene, was born.

Roy grew up in a middle class neighborhood of Salt Lake City’s Fourth Ward. The city itself had a population of around 45,000 during his childhood. It was also becoming a more diversified place to live. About half the population did not belong to the Latter-day Saints Church, though Roy and his family were members. When Roy was ten, Utah became the 45th state.

Castleton was well educated by turn-of-the-century standards: He was a high school graduate who especially enjoyed mathematics. His other passion was baseball.

By the summer of 1904 he was using both talents. He joined his older brother Charles as a member of the state’s best amateur team, the Cleveland Commission company team of Salt Lake City. According to the Ogden Standard Examiner the team included several former professional players and was the undisputed amateur champion of the state. Not yet 18, Roy more than held his own in a series of games with an independent professional team from Ogden. On July 3, he lost a 6-5 fourteen-inning game. The Standard Examiner said Castleton “handled the horsehide in good style, and finished with a strong wing at the end of the fourteenth inning.” Before a thousand fans, the largest crowd of the season in Ogden, he won the next day by the same 6-5 score, with his endurance noted. He went 3-4 at the plate that day.

At some point late in the 1904 season, Roy signed with his hometown Salt Lake City team in the Class B Pacific National League. He probably played at least briefly with the team in the closing weeks of the season, and was included on the team’s reserve list that fall.

During the winter of 1904-05 Frank Gimlin, manager of the Cleveland Commission team, was hired by Ogden as the team entered the Pacific National League.

Gimlin recruited some of his former players, including acquiring Castleton from Salt Lake City. Only nineteen, Castleton seemed overmatched by the more experienced competition, but he made the team and pitched well at times. His best outing was a sixteen-inning loss at Salt Lake City.

After the league collapsed in June, the Ogden team stayed together as an independent team, and Roy also earned extra money pitching for a semipro team in Blackfoot, Idaho. In Blackfoot, he pitched under an assumed name, taking the name of Sweeney, the pitcher he’d replaced. The Los Angeles Times later told the story of Castleton’s last appearance as “Sweeney.” “Blackfoot fans ran a special excursion [train] down to Idaho Falls. Unfortunately, a traveling man from Salt Lake happened to be among the excursionists. He recognized Castleton. Just before the game started, a prominent citizen of Idaho Falls, with a Gatling gun in his pocket, stepped to the plate and announced that Blackfoot had a ringer in the box and declared all bets off. Neither side scored for three innings, and a lot of new bets were made in the meantime. Blackfoot won in a driving finish, and Castleton at once became the center of interest. Roy started for the depot on [sic] a gallop. He hastened in every respect of the word. Almost anyone would be prone to hasten with a large portion of the population of Idaho Falls and surrounding country in his wake and considerably peeved. After great difficulty, Castleton was hoisted on board a train for Blackfoot.”

When not pitching or being chased by angry fans, Castleton worked as a clerk and bookkeeper for one of the railroad offices in Salt Lake City. In the spring of 1906, he took one of those trains east.

Youngstown, Ohio, had been a hotbed of professional baseball for several years. After a few seasons of independent ball, the city along with many others entered organized ball in July of 1905 as part of the Class C Ohio Pennsylvania League (O-P). Despite the jumble of teams and inconsistent scheduling, Youngstown had a strong team and was ruled league champion. By 1906, the league had shrunk to a more manageable eight teams, six of them in Ohio.

Although the league was new, O-P teams had established rosters largely consisting of veteran players. Most of the Youngstown players that spring were at least four or five years older than Castleton, the youngest player on the team. At a listed height of 5-11 1/2 and 150 pounds, he was one of the team’s tallest players but looked like a man who’d missed a meal or two.

Youngstown manager Marty Hogan, a former outfielder, was an outstanding judge of pitching talent. Later he’d be responsible for signing Stan Coveleski and Sam Jones to their first minor league contracts, but in 1906 Castleton was his find.

It took just one exhibition game to impress the Youngstown Telegram: “Roy Castleton has a jump ball that has it on anything else seen in this neck of the woods. When he has the ball working right a batter has trouble in sending it to the outfield.”

Castleton made his first regular season appearance in Youngstown’s third game. He beat Newark 6-3 but had to be relieved after six innings. The Telegram said he was “plainly rattled and only the clever work in the outer garden held Youngstown safe.” He gave up five hits, struck out two, and walked one. It was still a better debut than that made by another young southpaw a few days later. Richard Marquard, already nicknamed Rube, lasted just one third of an inning in a relief appearance for Lancaster, allowing five runs on seven hits.

Castleton won four of his first five decisions, two of those wins in relief, and the Telegram said, “with a little coaching by the veteran catcher, Lee Fohl, [Castleton] should develop into a real wonder. Roy has not been backing up the bases well in the games he has played, probably due to a little nervousness, but he will soon overcome this. He has an abundance of smoke, good curves and excellent control.” The Telegram noted those curves were “breaking much better in practice than in the games in which he has participated but each game shows an improvement.” The article predicted that he would be the best southpaw in the league by the end of May. That prediction wasn’t far off.

Even when he was struggling on the mound, Castleton was one of the league’s better gate attractions. He told a Utah newspaper that he was called “the tall Mormon pitcher, or Brigham Young. While on the coaching lines the fans were continually asking how many wives he had at home, all of which he took good naturedly. Whenever Castleton was slated to pitch, it was used as an advertisement by the home teams and generally resulted in bringing out a large delegation of girl fans who wanted to see the man with many wives.”

July, Castleton’s strongest month, marked the first mention of major league interest in the young southpaw. The sports editor of the Youngstown Telegram received inquiries from three unnamed major league managers, and Hogan was also contacted about the 20-year-old pitcher.

On the field, Castleton was developing the consistency the Telegram had predicted. He won six of seven starts and also won a game in relief. His record stood at 15-8 the morning of August 17. That game would make Roy Castleton famous.

It was the second game of a key series between first place Youngstown and second place Akron. Hogan felt Akron was weak against lefthanders and decided to pitch Roy outside his normal spot in the rotation. The next day’s Telegram reported, “In the most remarkable game ever seen in Youngstown, remarkable for the great pitching of Roy Castleton, Youngstown shut out Akron 4-0. Akron never had a lookin [sic], not at a run, nor a hit, nor even first base. Castleton was in anything but a generous mood and although the visitors were of the opinion that he might ‘open up’ and permit one or more of them to get to first base, the Mormon youth thought otherwise and not a single Tip Top made the acquaintance of Mert Whitney at the initial sack.”

The Telegram also compared Castleton’s perfect game to the one thrown by Cy Young the year before. “In that memorable contest Young did not allow a run nor a hit. He did not give a base on balls nor hit a batsman. Castleton not only did this Friday but he went old Cy a few better. Only four balls were batted out of the infield. The Mormon also compelled ten men to fan the atmosphere.” A dropped third strike was the closest Akron came to a baserunner, but catcher Fohl threw the runner out easily.

Major league managers took notice of the perfect game. When Youngstown went to Mansfield for their next series, one of those in attendance was Clark Griffith, manager of the New York Highlanders. He offered $2,000 for Castleton with the young pitcher reporting to New York immediately. The team’s owners turned down the offer, as Youngstown was in a tight pennant race.

Roy was considered one of the most gentlemanly players in what wasn’t a gentlemen’s league. Still on one occasion late in the season his temper got the best of him. The Telegram noted, “Roy Castleton, the Mormon youth, is not immune when it comes to saying cuss words. Of course Roy uses them in a modified form but just the same he uses them. Umpire Sam Wise‘s eyesight was very bad, and he sent three men down to first in succession in the first inning, a run being forced across the plate. Both Castleton and Fohl claim that over one half of the balls cut the plate almost in two, and were of regulation height. Sam couldn’t see them that way, however, and Roy expressed his opinion of Wise in anything but a complimentary manner.” That bases loaded walk was decisive as Castleton lost the game to Akron 4-3.

With a month left in the O-P season, Griffith got his man. New York drafted Castleton for the standard Class C price of $500. Because of his being drafted Youngstown retained Roy for the rest of the season. He finished by winning his last five decisions, finishing with a 22-12 record and striking out 156 batters in 278 innings.

Castleton reported to New York’s spring training site of Atlanta, Georgia, on Saturday, March 9. Alexander MacKenzie, sports editor of the New York Mail, said of Roy’s early workouts: “The most promising [of the rookie pitchers], to my notion, is the young lefthander, Castleton. He has better control than any lefthander seen in the East for many years, and had so much speed that Griff had to stop him a couple of times during the practice.”

Sid Mercer of the Globe also wrote about the young southpaw: “Jack Kleinow was doing the receiving. Presently the ball began to produce loud and resounding thumps in his big mitt. He was faster than it really looked possible for him to be. Then he began hooking them over, and Griff’s eyes opened wider, for Castleton was throwing one of the best curves which Griff had ever seen so cleverly controlled by a young southpaw.” Kleinow said of that curve, “A right handed batter will fall for that ball every time, it breaks so quickly, though, that he can’t dodge, and even if he doesn’t intend to hit, he will throw up his stick to protect himself. The usual result is either a pop fly or an easy grounder, with the runner getting a bad start to first.”

After splitting their first two regular season games, New York opened at home against the Philadelphia Athletics. Despite bad weather, the New York Times estimated the crowd at 10,000. Five pitchers were used between the two teams that day. Roy Castleton was the third of three pitchers to appear for New York. Entering the game in the top of the ninth, he worked a hitless inning.

After nearly a week of inactivity, Castleton was the starting pitcher in an exhibition contest with Newark of the Eastern League. On a cold afternoon marked by occasional snow, he allowed thirteen hits in a 12-3 loss. Two days later he was optioned to Atlanta for more seasoning. Though he’d barely pitched in a month, Castleton’s debut in the Southern Association was impressive. On April 29 he beat defending champion Birmingham 5-1. Roy allowed just four hits and struck out seven.

His third Atlanta appearance illustrated both his potential and his flaws as a pitcher. He was dominating early, striking out four batters in the first two innings. He finished with ten strikeouts in a thirteen-inning tie at Memphis, but struggled badly in the eighth inning. An error and a pair of walks that inning let Memphis score both their runs. He walked six in that game. He later appeared in two twelve-inning games, winning one and tying the other. Those were Atlanta’s three longest games of the season.

Three losses and a brief period of inactivity with a sore arm slowed his progress through the last half of May. The Atlanta Constitution was still impressed with the young southpaw: “He was bumped on the road, but that was a natural occurrence; no one holds it against him, nor does anyone lessen the value placed on him when he was winning so regularly, and receiving the plaudits of the multitude. He promises to get more plaudits as well as bumps.”

Not all the bumps he received were on the field. Shortly after joining Atlanta, an imaginative newspaper reporter claimed he was a Mormon with sixteen wives. A report a few years later in the Los Angeles Times said Castleton had been visited by “representatives from the various civic bodies, the W.C.T.U., and The Women’s Foreign Missionary Society. If Roy actually had sixteen wives, it was deemed advisable to ride him out of town on a rail. Roy established his singleness to the satisfaction of all concerned and continued to remain in the circuit until called higher.” Though certainly exaggerated, this incident showed some of the off-field distractions that Castleton had to face pitching in the South.

June and July of 1907 were successful months for Castleton. He won 10 of 13 decisions for Atlanta, developing into the league’s best lefthander. One of his best midseason outings was on July 4. The Constitution said: “the southpaw had them on the on the blink throughout the nine rounds, pitching almost faultless ball the while. The small covey of hits [three] were scattered here and there, and in that condition were worthless.” He was more effective on the road than at Atlanta’s Ponce De Leon Park. He said the mica soil of the pitching mound had a negative effect on his control.

As well as Castleton pitched the first four months of the season, he saved his best work for the heat of the pennant race. On August 30, he shut out Little Rock on four hits. No runner reached third. Three days later he struck out nine Shreveport batters throwing a five-hit shutout, winning 5-0 in the second game of the Labor Day doubleheader. He threw his third straight shutout on September 6, blanking New Orleans by an identical 5-0 score. His final 1907 start for Atlanta was his fourth straight shutout. It was a classic pitching duel against Memphis’ George Suggs. Suggs allowed five hits, striking out eight and walking two. Castleton was even better. He allowed just four hits with eight strikeouts and one walk. Appropriately the contest ended in a scoreless tie. His final record with Atlanta was 17-8, and he was generally considered the best pitcher on a staff that included Russ Ford and Bob Spade. When an all-time Atlanta team covering the years 1902-07 was picked the following spring, Castleton was among those chosen.

Griffith exercised his option on the young southpaw, and Castleton rejoined New York at the end of the Southern Association season. He made two starts during the last week of the American League season. His first start was in the opener of a doubleheader against the St. Louis Browns on September 28. The game was a classic deadball era game. Castleton retired the first twelve Browns he faced before Bobby Wallace opened the fifth with an infield single. St. Louis scored two in the sixth and added another in the seventh for a 3-1 win. Despite the loss, Castleton was very effective, allowing five hits, striking out two and walking one. The New York Times said of his first start, “The Southern League graduate soon installed himself as a favorite of the fans.”

Castleton’s second and, as it turned out, final American League start was on October 2 against Doc White and the Chicago White Sox. New York scored four runs in as many innings off White, and Castleton could be described as effectively wild that afternoon. Charles Dryden’s account of the game in the Chicago Tribune commented on Castleton’s control in humorous fashion. “After [Jiggs] Donahue doubled in the second Castleton filled the bags by hitting two athletes [Patsy Dougherty and Hub Hart] in vulnerable spots below the belt. By the time he had done all these heroic stunts two men were out, Dr. White mortified his colleagues by fanning the air which was cool enough.”

Through the first five innings, Castleton allowed the defending World’s Champs just three hits. Dryden’s account described a Chicago three-run rally: “The Sox bubbled in the sixth. Donahue soaked a safety. [George] Davis fanned. [Charlie] Hickman [replacing the injured Dougherty] got hit on the excess baggage. [George] Rohe‘s smash to left bounded over the low bleacher fence for a home run.” Dryden claimed the home run “got Castleton’s goat,” and after getting out of the inning with a one-run lead, “Castleton was so glad he was alive he at once turned over his portfolio to slow Joe Doyle.” Doyle held Chicago scoreless, saving Roy’s first major league win. Despite the three- run inning, Castleton still pitched well, allowing six hits, striking out three, walking one and of course hitting the three batters below the belt.

After the season ended, Castleton returned to Salt Lake City and his work in the railroad office. He later said, “I have to work. If my mind is not occupied, I get to thinking too much about things and consequently get blue. And I have to work at something that will keep me going hard. I never felt better than when I had whole sheets of figures to add in making trial balances. The more the merrier. And if I got hold of something with about fourteen columns a mile long each, and about five sheets of them, I was in my glory.” He said he usually got off work early enough to keep in shape with an afternoon workout.

Despite Castleton’s solid pitching, Griffith decided he needed a little more seasoning. In late February, Griffith optioned Castleton to Atlanta for the 1908 season. The option to Atlanta was meant as park rental for New York’s spring training stay.

Castleton’s 1907 salary was a controversial topic in the spring of 1908. The Memphis Commercial-Appeal claimed the Atlanta groundskeeper “was paid an enormous salary. This, of course, did not appear on the players’ payroll, but it is charged was cut up with a star pitcher, who received his salary partly in check form, with the remainder in cash handed as a ‘present’ from the keeper of the grounds.” Action was threatened against offending clubs by the league president, but nothing was proven.

An on-field spring highlight was a March 28 start against the Cubs. When Castleton left after five innings, the Crackers led the defending World Champions 3-2. After allowing a pair of runs in the first, Castleton was very effective. The Constitution reported, “He worked four more rounds and there were but two more hits, far apart as hits should be when the home team is not getting them.”

Abnormally cool weather contributed to a slow 1908 start for the Atlanta southpaw. Exaggerating somewhat, the Constitution said of his first start against Nashville, “By the fourth round icicles began to form on his hurling wing.” He pitched well in a loss that day but lasted just two innings in his second start. He didn’t pitch for three weeks after that, probably due to injury.

When Roy returned to the mound at Little Rock on May 13, he had a new pitch that was helped by adverse weather conditions. The Constitution reported, “Heavy rains of the night preceding soaked through the crust at West End Park, and made the going bad, even for web footed and water-wagon stars of the diamond. The ball was slippery and spitters served by Castleton were not necessarily wetted by the Mormon’s saliva.” He allowed two hits and struck out ten that afternoon and had “local batters up Salt Lake all the way through.”

He lost his next two starts to drop to 1-4. The second of those was an eleven-inning 2-1 duel at Mobile. That game was a turning point as he won his next eight decisions between May 30 and July 4. It seemed as if another outstanding season and a return to New York was in store, but disaster struck during a road trip to New Orleans.

Typhoid fever was a dreaded disease a century ago. George Grossart, Cozy Dolan and minor-league player-manager Julius “Hub” Knoll had all died of typhoid in the early years of the twentieth century.

However, there was no mention of typhoid or indeed any serious concern when Castleton returned to Atlanta on July 10. Within a week, the Constitution reported that he was “a very sick man…and is out of the game for the remainder of the season.” He spent his twenty-third birthday in the hospital, receiving flowers from members of the Atlanta and Mobile teams.

He lost 35 pounds by the time he left the hospital after forty days. He also lost a chance to return to New York. As part of the agreement when Castleton was loaned to Atlanta as park rental, New York got the pick of the Atlanta roster. When the option was exercised in August, pitcher Russ Ford was chosen instead. At the time, Ford was 13-11, while Castleton had been 10-5 at the time of his illness.

Despite missing about half of the season, Roy was chosen on at least one Southern Association All-Star team for 1908. The team, chosen by Constitution sports editor Dick Jemison, also included past and future major leaguers Ted Breitenstein, Bill Bernhard and Tris Speaker.

Off-season reports indicated Castleton was regaining his health, and expectations were high for the 1909 season. A development in the major leagues would also affect his career. Griffith left New York to become manager of the Reds, and decided to move Cincinnati’s spring training base to Atlanta.

During spring training, it seemed Roy would return to form after his serious illness. After two impressive spring starts against South Atlantic League teams, Griffith purchased an option for Castleton’s services. The option required Cincinnati to acquire his contract from Atlanta on or before August 20.

But Roy struggled after the impressive start, walking five in a 4-3 loss to Birmingham on opening day.

Castleton’s next start was even worse. He lost 11-7 at Nashville and also argued with catcher Syd Smith before leaving the game. Roy dropped to 0-3 before finally winning the first game of a doubleheader against Birmingham on May 1. He won that afternoon 3-0 in ten innings, allowing five hits while striking out ten and walking two.

Despite the strong outing, Castleton appeared in just one more game for Atlanta. Just days later, Roy was sent home with an illness first described as malaria and later as food poisoning. Rumors of an impending release were also circulating.

Those rumors became reality, at least in part, on May 16. Cincinnati exercised their option early and purchased the southpaw. Roy offered an insight as to why he wanted out of Atlanta: “I do not feel I can stay in shape in this climate. Atlanta is all right, and so is Nashville, but when I get to the other towns, I get sick and don’t feel like working. I feel with a little rest up and a cooler climate I will be myself and able to do good work, and I hope to give Cincinnati the best there is in me.” Atlanta manager Billy Smith said the purchase price was $1,500 and agreed the move was made at Castleton’s request.

Upon reporting to the Reds, Castleton didn’t pitch for nearly a month. He finally got into a game for the Reds on June 9. The Reds and Boston had a doubleheader scheduled, but due to rain and darkness just one game was played. An estimated 2,500 fans witnessed a 13-2 Reds win that afternoon. The Boston Globe described him as “a rather slight southpaw.” The Globe was impressed with his National League debut. “True, he allowed 11 hits, but these were so nicely distributed that had not [first baseman Dick] Hoblitzel made a mess of a rap in the seventh inning, not a run would have trickled over the plate for the Doves. Castleton began the work of destructor in the first inning by fanning [Johnny] Bates and [Fred] Stem and causing [Bill] Sweeney to roll out. In the second he got [Ginger] Beaumont and [Claude] Ritchey on flies and downed [Bill] Dahlen by the three-whiff route.” Castleton finished with four strikeouts and just one walk.

Unfortunately, Castleton’s physical problems continued. Ring Lardner reported Castleton was in Waukesha, Wisconsin, trying to regain his health while the Reds were playing in Chicago. He soon returned to the Reds but was used infrequently. He pitched in a mop-up role in games at Pittsburgh and Boston, before entering a July 25 game versus St. Louis in the eleventh inning. The appearance was a disaster. He allowed three hits and walked three in two innings, giving up three runs in two innings of work. The loss evened his record at 1-1. As it turned out, this was his last appearance of 1909.

Brooklyn pitcher Nap Rucker had a brief vacation from his team in early August and discussed Castleton’s health with a reporter from the Atlanta Constitution. “Roy does not look well, and it is doubtful if the boy ever pitches again. He told me himself that he was leaving for his home in Salt Lake City for the remainder of the season.”

Castleton reported early to the Reds 1910 spring training site, Hot Springs, Arkansas. He started the season with Cincinnati, but pitched just once in the season’s first month.

Ring Lardner described his inauspicious debut versus the Cubs: “Castleton went in to pitch for the Reds in the fifth. He lasted about a minute. [Ginger] Beaumont and [Frank “Wildfire”] Schulte singled and [Frank] Chance sacrificed. Steiny [Harry Steinfeldt] walked. With the bases full, Castleton uncorked a wild pitch and Beaumont loafed home. Griffith asked O’Day to call time while he switched pitchers, and Hank sent him off the field for too much talk.” The two runners left on base scored, and Castleton was the losing pitcher that afternoon.

It was almost exactly a month before Griffith gave him another chance. On May 15, he made the most of a rare start, beating Nap Rucker 2-1 in a pitcher’s duel. Castleton allowed five hits, walked five and struck out three. Given another start against the Giants four days later, he was knocked out in the third after surrendering four consecutive singles. Castleton would make just one more major league appearance. He entered a May 29 game against St. Louis in relief of Jack Rowan in the fifth and was the losing pitcher, working just 1 2/3 innings.

When Cincinnati started on an eastern road trip after that series, Castleton didn’t go with them. Instead he went west. The Reds sold him to Los Angeles of the Pacific Coast League. Whether it was after effects of his 1908 illness or inactivity, Castleton’s contribution to the 1910 Reds was minimal.

Having expressed an interest in pitching closer to home, Castleton now had the chance. In his debut at San Francisco on June 18, he struck out ten and allowed just four hits in eight innings. The Los Angeles Times said of his debut: “It is some time since a new pitcher has shown greater promise than Castleton. He has the speed of any twirler in the league, and his ball breaks in a most bewildering jumping fashion. Nearly every Seal succumbed to his curves during the afternoon, and his cool confident manner made him many friends among the crowd.” Nevertheless, he lost the game 4-2.

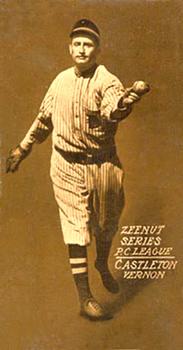

On July 16, Castleton was even better, throwing a one-hitter against crosstown rival Vernon. He gave up a single to the second batter he faced and walked just one batter that afternoon. According to the Times, “Castleton’s heaving has not been exceeded on the Coast this year. The Hooligans [Times nickname for Vernon team] knocked the ball right into the fielders’ hands and everything was handled in major league fashion. Several pretty catches and stops and throws gave the fans plenty of opportunity to howl.” The game was a typical deadball era pitcher’s duel. Castleton won 1-0.

Roy seemed to have regained his pre-illness form, but the rest of the season was a struggle. Some of it was wildness. In a couple of late July losses, he allowed multiple walks at inopportune times leading directly to the loss. Through late August his record was just 4-7 with 65 hits and 33 walks surrendered in 66 innings.

Still, it was lack of fielding support that attracted the most comment by Castleton and by the Times. The Times account of a 3-0 September 12 loss to San Francisco summed it up: “Castleton said some time ago that every time he pitched, a lot of the boys hauled their gum boots out of the clubhouse and put them on so they could kick the ball around. Whether or not this is true is another story, but the fact remains that the Angels threw the pill around in a weird way at times yesterday and the Seals got two runs off the weirdness.” The Times commented on poor defensive support for Roy several other times that season, even offering the opinion that the poor defense discouraged him and diminished his effectiveness. Whatever the cause, he finished 1910 with a less than impressive 8-15 record with 95 strikeouts and 68 walks.

Though originally expected to remain with the Angels for the 1911 season, the Los Angeles manager asked for waivers on Castleton. Hap Hogan, manager of crosstown rival Vernon, claimed him in early February.

Castleton opened the 1911 season with Vernon as one of seven pitchers on the staff. After an undistinguished relief appearance, he started his first game of the season at San Francisco on April 1. He shut the Seals out 4-0 that afternoon and received positive comment in the Los Angeles Times: “San Francisco players were bowled over with the rapidity of a crack rolling a big ball down the alley. A couple of their men did reach second, but Castleton scattered his five hits over as many innings, and there was no question but that the Seals were hopelessly distanced. Castleton, for a southpaw, was remarkably steady, allowing but one walk.”

He won his next start 4-2 at home against Portland on April 6, shaky control working to his advantage. The Times described him as “fearfully and wonderfully wild at times, and, in addition to three bases on balls, he made two wild pitches. The fact that he didn’t bounce the ball off any solid-ivory heads shows that the Beavers were pretty much there in the ducking line.”

After a couple of losses, Castleton finished April 1911 with a flourish. He beat Oakland twice in the same series, one by a shutout, but he saved his best effort for his last start of the month. On April 28, Vernon faced the crosstown rival Angels, and Roy pitched his third shutout of the month. The Times said of the game, “what he did to them [the Angels] was what John D. Rockefeller does to all of us. He simply hung out the sign that it was his busy day and consequently there were no transactions in the run line. Castleton just made monkeys out of them. [He] curved them around their necks, fanned seven of them and those who could hit the pill out of the infield thought they were lucky.” He allowed just five hits while improving his record to 5-2.

Roy struggled during May and June. He lasted two and one innings, respectively, in a pair of starts at Sacramento. He also was knocked out after two innings in a mid June start against Portland. The Times offered colorful comment on the game: “Castleton thought early yesterday morning that he understands something about heaving, but early yesterday afternoon he didn’t think so. In fact, he did not think much of himself. If he did think it couldn’t have been much, for the champions slammed him for eight runs and six hits in the first two innings. This was naturally all he wanted, and he was glad to get under the bench where they could not even see him.” His control was abysmal that day. He walked five batters in the first inning.

The team’s performance was as inconsistent as Castleton’s. The fortunes of the team and the pitcher began to change during a July road trip. He shut out San Francisco and Portland in consecutive starts and won another game in the series at Portland with his arm and his bat. He allowed just four hits in ten innings and singled in the winning run. He won seven consecutive starts in July and August, allowing five or fewer hits in four of the games. During the streak, Vernon took the lead in a tight pennant race.

By mid-September the Tigers were in Portland facing their top competition for the PCL pennant. His manager hoped to use him twice in the key series, but it rained on Tuesday, September 14. Castleton slipped on wet pavement that afternoon and sprained an ankle. He pitched in the first game of a doubleheader three days later, but seemed to be affected by the injury. Poor defense and six walks helped the Beavers to a 5-4 win, and a win in the second game gave them a decided advantage with a month left in the season.

Castleton recovered quickly from the injury, shutting out Sacramento and allowing just one run on five hits against Los Angeles. The latter win tied Vernon for the league lead, but fatigue was evident. He didn’t win another game, and was hit hard in two October starts. He finished the season with a 22-13 record, striking out 146 and walking 76 in 327 innings. The heavy workload would take its toll.

Though there was a brief misunderstanding about his contract, Castleton soon signed with Vernon for the 1912 season. According to Roy, “There was some mistake in my address and Hap’s letter containing the contract lay in the post office unclaimed since January 5. As I did not hear from Hogan by February 1 I thought I was free, according to the new rules. Since February 5 I have heard from Hogan and believe everything is all right between us.” He spent the off-season working in the auditor’s department of the Oregon Short Line Railroad and kept in shape by shoveling snow and playing hockey.

After reporting for spring training, Roy began the season well. He pitched impressively in exhibition games, including one against the University of Southern California, and was counted on to play a major role in Vernon’s hopes for the pennant.

Castleton struggled in April, but seemed to return to form in May. After a victory over Oakland on May 12, the Times said, “A double hop that Castleton put on what he had yesterday sewed the Oaks up into knots and easily won him a ball game with apparently little effort on his part.” Castleton won six out of seven starts, completing them all, between April 28 and May 26.

It seemed he was on the verge of another outstanding season, but the innings were taking their toll. Castleton missed a month with what was described as a wrenched back and injured pitching arm.

Returning in late June, Castleton won three straight decisions but was evidently still pitching in pain. Of one of those wins, the Times said, “Portland secured enough hits [ten] off Castleton to win an ordinary game, but this much must be said for the southpaw, he breezed along under half speed until forced to show his colors then tightened up short.”

By the beginning of August even this didn’t work. Roy was seldom able to finish what he started. Since Vernon was in another pennant race, he continued to take the mound, and resented being removed. After he was taken out in the tenth inning of an eleven-inning loss to Los Angeles, the Times described Castleton as “about as sore as a half-boiled owl when he was yanked, for he had pitched a fine game up to that time.”

Pitching in pain, Roy soon took his frustration out on Los Angeles Times reporter Grey Oliver. After being removed in the fifth inning against Oakland On August 16, he said, “What do you think. Me going out there with a sore shoulder and then them stickin’ Stinson in right field with a broken leg and not able to catch fly balls that any man would have caught if he was right. Guess if some of those fly balls had been caught there would not have been so many hits. And then you fellows say we are knocked out of the box.”

Castleton completed just one game after August 1, 1912, but it was a masterpiece. On September 4, he won a key game against Vernon’s top competitor, Oakland. He shut the Oaks out on four hits. The Times said: “Castleton pitched ball like a champion. He had all those Oaks going south and they knew it. He never was in danger. Up to the eighth round, only two drives had been registered against the left hander. Two more were bunched in the eighth, but this did not do any good, for as soon as they were made, Castleton tightened up and the men behind him made short work of the struggling Oaklanders. They were simply outclassed.”

Henry Heitmuller, the PCL’s leading hitter, died of typhoid fever on October 8. The death must have affected Roy as much as it did Heitmuller’s teammates. It almost certainly brought back memories of his own struggle with the illness and probably had a major impact on a decision he’d have to make a few months later. The day of the funeral in San Francisco, the Los Angeles- Vernon game was stopped for ten minutes in the third inning. Castleton pitched and won that day though he was removed in the eighth inning. That game was his final win of the season–and his career. He had one final appearance after that, saving a win in the first game of the Tigers season ending doubleheader win over Portland.

He finished 1912 with a 13-8 record in 222 innings striking out 92 and walking 83. He hit .152 in 79 at-bats. After the season he reportedly toured Australia with a PCL all-star team organized by J. Cal Ewing of Oakland.

Shortly after the season it became clear that Castleton wouldn’t return to Vernon. A rumored trade to Portland fell through, and in late January of 1913, he was sold to Nashville of the Southern Association. An early report said he’d signed with the team, but later news indicated he was holding out. An April 7 article in the Atlanta Constitution said, “while in the shadow of Brigham Young’s temple, out in Utah, Roy Castleton is wailing to be shipped to some climate where the typhus germ is an alien.” Perhaps if the Nashville ballpark hadn’t been flooded and Vols manager Bill Schwartz hadn’t been stranded in Ohio, also due to flood, a deal might have been worked out. It wasn’t and Roy Castleton retired from baseball.

Despite bad memories of Southern baseball, Roy was still mentioned among the best to play in Atlanta and the Southern association into the 1920s on the strength of his success in 1907 and the first half of 1908.

On July 9, 1918, Roy married 25-year-old Esther Kelson in Salt Lake City. At the time he was working as an accountant for Scott & Hadley, a stock brokerage firm in Salt Lake City. Roy, Esther and several of his siblings continued to live with his parents at least until Charles Castleton Sr. died in 1922.

Roy and Esther had no children and later moved to Los Angeles, where he worked as a water heater inspector. Suffering from diabetes, Roy died there of a cerebral hemorrhage on June 24, 1967, and was returned to Salt Lake City for burial in the Salt Lake City Cemetery.

Sources

Newspapers

Ogden (Utah) Standard Examiner, 1904-08.

Youngstown (Ohio) Telegram, 1905-06.

Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal, 1905,06,09.

Lancaster (Ohio) Gazette, 1906

Lancaster (Ohio) Eagle, 1906.

Newark (Ohio) American Tribune, 1906.

Dayton (Ohio) Journal, 1906,09,10.

Toledo (Ohio) Blade, 1902.

New York Times, 1907, 1910.

New York Mail, 1907.

New York Globe, 1907.

Atlanta Journal, 1907.

Atlanta Constitution, 1907-09, 1912-13, 1921.

Chicago Tribune, 1907, 1909-10.

Boston Globe, 1909-10.

Washington Post, 1910.

Los Angeles Times, 1910-12.

Salt Lake City Tribune, 1967, 1987.

Other Baseball Sources

SABR Online Encyclopedia.

Wright, Marshall, Southern Association in Baseball, 1885-1961 (McFarland).

Lee, Bill, Baseball Necrology (McFarland).

Jones, Kevin, e-mails December 2005.

Nelson, Rod, e-mail July 2005.

Wendt, Paul (forwarded by Kevin Jones) e-mail December 2005.

Census

Utah, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920.

Other Genealogical Sources

Passenger Lists Port of New York.

World War I Draft Registration Card Royal Eugene Castleton.

Utah Pioneers and Prominent Men.

Ancestor Histories Salt Lake City Chapter Sons Of Utah Pioneers.

Other Online Sources

Jensen, Richard L., “Immigration to Utah,” (Utah Historical Encyclopedia).

Kimball, Stanley, “Mormon Trail in Utah,” (Utah Historical Encyclopedia).

McCormick, John S.,” Salt Lake City” (Utah Historical Encyclopedia).

Full Name

Royal Eugene Castleton

Born

July 26, 1885 at Salt Lake City, UT (USA)

Died

June 24, 1967 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.