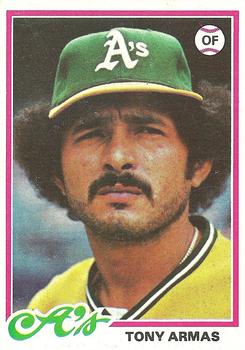

Tony Armas

In the 2015 season, Miguel Cabrera surpassed Andres Galarraga as the Venezuelan with the most home runs in the major leagues. His 400th home run, on May 16 at St. Louis, gave to the Detroit Tigers first baseman a record that had been held by the “Big Cat” since 1997, when he eclipsed the record of the first great Venezuelan slugger, Antonio Rafael Armas Machado.

In the 2015 season, Miguel Cabrera surpassed Andres Galarraga as the Venezuelan with the most home runs in the major leagues. His 400th home run, on May 16 at St. Louis, gave to the Detroit Tigers first baseman a record that had been held by the “Big Cat” since 1997, when he eclipsed the record of the first great Venezuelan slugger, Antonio Rafael Armas Machado.

Tony Armas was born on July 2, 1953, in Puerto Piritu, Anzoátegui state, a town in eastern Venezuela, 235 kilometers (about 150 miles) from Caracas. His father, Jose Rafael Armas, was an electrician, while his mother, Julieta Machado de Armas, was engaged in household chores, taking care at home Antonio and his 12 brothers.

“My parents were able to keep me on track,” Armas said. “We were a very poor family, and lived on what was achieved. My dad was a farmer too.”

In a place having beautiful beaches, the Armas family also had land that they worked. “We used to plant all kinds of beans, all kinds of fruits. We were poor and planted all kinds of fruit for the sustenance of the house,” Armas said. “As the oldest I was the one who was in charge of that, to load sacks of corn, pumpkin, watermelon, everything that was harvested. I think my strength came from there.”

There was no Little League or the Criollitos of Venezuela in those days, no organized movements that help children and young people today to start polishing their skills. Armas began to imitate his idols playing baseball in the street with older people in his neighborhood.

“There were no baseball schools, no little– league baseball. You become a baseball player through hard work,” he said. “I played caimaneras (baseball in the street) with adults, as everyone did in those days. I played since I was a boy, since I was in school. It is not like today, when children are born with a uniform. Right now they have coaches, all benefits that a little boy may have from birth until (he) reaches his youth. At that time, no, at that time you had to make yourself as a player.”

At 17, Tony played for the first time on a team in an organized league, Deportivo Pachaquito, and began to develop his skills on defense.

“I ended up not playing the tournament,” he recalled. “I started the championship, but didn’t finish it, because there was a National Youth Championship, to be played in Cumaná city and as I was 17, I was called from the Double A to the youth team to go play.”

Armas had an outstanding performance, starring as his team won the Anzoátegui state title. He was called to the national team to play for the World Youth Championship in Maracaibo. That was where he caught the attention of the former major leaguer Pompeyo “Yo– Yo” Davalillo, a scout for the Pittsburgh Pirates.

Davalillo, brother of the former All– Star Vic Davalillo, played in the majors in 1953 with the Washington Senators, but a broken leg shortened his career and he devoted his life to trying to recruit players from Venezuela to play in the United States.

“Pompeyo Davalillo had checked me in both the national junior and youth world championships. I also went to a worldwide Double– A championship, in Cartagena, Colombia. I didn’t have much chance to play, because I was very young and we had players who were better prepared than me at that time. I did not play, but I had a pretty good time. I kept playing and in 1971 Pompeyo Davalillo arrived at my house, talked to me, said he thought I could make it to the majors, that I could go far in baseball. He spoke with my parents and that’s how I started my career.”

On January 18, 1971, Armas signed as a free agent with the Pittsburgh Pirates for $5,000. At the same time he signed for 30,000 bolivars to play Venezuelan winter ball with the Caracas Lions, a club that had previously featured two of his idols, Vic Davalillo and Cesar Tovar. Tovar played in the majors from 1965 to 1976 with the Twins, A’s, Rangers, Phillies, and Yankees, with a lifetime average of .278; Davalillo batted .279 between 1963 and 1980 with the Indians, Angels, Cardinals, Pirates, Dodgers, and Athletics.

“I was a fan of Caracas and my favorite players were Cesar Tovar and Vic Davalillo. I also admired Joe Ferguson, a power hitter who came as a foreign player.” Ferguson, who played 14 seasons in the majors with Dodgers, Cardinals, Astros, and Angels, played with the Lions in Armas’s rookie year in Venezuela and batted .294 with 15 homers and 51 RBIs, an inspiration for the young prospect.

“I think they signed me because I was a good outfielder. I was not a good hitter,” he said. “You learn to hit with constant work.”

Pittsburgh assigned Armas to play with Monroe and with Bradenton in 1971, dividing his time between rookie ball and Class A, where he combined for a .230 batting average; it was clear he had to work harder to improve his offense.

“I was a good outfielder and I realized I had to work twice (as hard as) the Americans to keep my job. That’s the way it was at that time, not like now, when someone comes to the majors with a lot of money and have to call you up. Plus there are more teams now. That is the reality of my career.”

In 1972 Armas batted .266 with 9 homers and 51 RBIs in Class– A Gastonia, and in 1973 he got the opportunity to play at Double A in an unusual way, after being a batboy for almost two weeks.

“Not that I was happy with what they were doing, but actually they had a lot of players in spring training. There were about 80 players in camp and on the field there were nine. I had no chance to play,” he said. “The manager of Class A needed a batboy and from among those 80 players they called my name. So I spent a week doing that. It bothered me a little bit, because I didn’t go up there to collect bats. I went to earn a spot. There was a Mexican named Mario Mendoza who helped me a lot; what I did was thanks to him, because I told him I wanted to go home, I was not up there to collect bats. He told me to stay calm, that I was being observed to see what kind of character I had, whether I was spoiled. I followed his advice and stayed. The next week was all the same. We arrived on Monday and started the game the same, ‘Armas, you’re the batboy.’ It turns out that on Wednesday, in a game between Double A and Triple A, the Double– A center fielder got injured. The manager shouted that they needed an outfielder and then he said, ‘Armas, get in there.’ I went in, and I stayed.”

His bat began to speak for him with Sherbrooke in the Double– A Eastern League; he hit .301 with 11 homers and 45 RBIs in 84 games, despite suffering a broken arm that had him away from action several days.

The young prospect continued his rise in the organization and, after another season in Double A in 1974, he was promoted to the Charleston (West Virginia) Charlies (Triple A) in 1975. With Charleston again the next season he showed some power, hitting 21 homers, and earned a call– up to the Pirates. Armas debuted on September 6, 1976, against the Philadelphia Phillies at Three Rivers Stadium. He replaced Richie Zisk in left field in the ninth inning. He played in four games during his call– up. On October 3, in the last game of the season (the second game of a doubleheader), Armas got his first start, in the lineup as the center fielder and batting sixth. He got his first major– league hit off Pete Falcone of the St. Louis Cardinals, a single to center field to lead off the bottom of the fifth.

Falcone was locked in a pitching duel with Jerry Reuss, and the game went into the bottom of the ninth scoreless. Armas came up with a runner on second base and two outs in the bottom of the ninth and singled to right field to give the Pirates a 1– 0 walk– off victory to end the season.

Still, Armas faced trying to break in to an outfield populated by Al Oliver, Omar Moreno, and Dave Parker.

“I had no chance to play, because the Pirates had many good players,” he said. “At the time I was in that organization was (Roberto) Clemente, Al Oliver, Willie Stargell, Dave Parker, Richie Zisk, and I had no opportunity to climb. In 1977 (I was out of options), so they had to keep me on the roster or trade me. At the last minute, they traded me to the A’s. It was there that I got the chance to show my full potential.”

Armas was sent to Oakland on March 15, 1977, along with pitchers Dave Giusti, Doc Medich, Doug Bair, and Rick Langford, and outfielder Mitchell Page, for pitcher Chris Batton and infielders Tommy Helms and Phil Garner.

Oakland, a rebuilding team, relied on the talents of Armas, who hit 13 homers and drove in 53 runs in 118 games. The next two seasons, he played in only 171 games because of injuries.

“In Oakland I obviously had to work hard, because no Latin at that time had a safety spot in the big leagues,” he said. “Thanks to Oakland I received the opportunity to play every day and I was able to prove myself.”

In 1980 Armas was healthy and able to deploy his strength to become one of the most feared sluggers in the American League. That year he hit 35 homers and drove in 109 runs, with a respectable .279 average.

The following year, in a strike– shortened season, Armas tied three other players for the American League lead in home runs with 22. (The others were Dwight Evans, Eddie Murray, and Bobby Grich. Armas drove in 76 runs, took part in his first All– Star Game, and finished fourth in the voting for the MVP award. He was chosen by The Sporting News as the Player of the Year.

Thanks to Armas and Rickey Henderson, the Athletics advanced to the playoffs and swept the Kansas City Royals in the Division Series. Armas was 6– for– 11 with two doubles and three RBIs. His bat cooled off in the ALCS against the New York Yankees (2– for– 12 with five strikeouts); Oakland was eliminated in three games.

Armas’s power caught the attention of the Boston Red Sox. He hit 28 homers for the A’s in 1982 and set an AL record for the most putouts in a game by a right fielder (11, on June 12 against the Toronto Blue Jays). After the season the Red Sox acquired Armas and catcher Jeff Newman in exchange for third baseman Carney Lansford, outfielder Garry Hancock, and Jerry King.

“They wanted a player who would protect Jim Rice and they made the deal,” said Armas, who was surprised by his departure from Oakland. For Boston, Armas played center field, although he wasn’t a particularly fast fielder, but with Rice and Dwight Evans he helped form one of the most powerful outfields in Red Sox history.

“It was a good team,” Armas said. He hit a career– high 36 homers, with 107 RBIs, topping 100 for the second time in his career, finishing with 107. Rice led the club with 39 homers and 126 RBIs, but Evans fell short with 22 homers and 58 RBIs, playing only 126 games in the final season of future Hall of Famer Carl Yastrzemski.

“It was a real experience to play with a superstar like Carl Yastrzemski was,” Armas said. “I met Ted Williams in spring training, and it was a great experience to meet those two legends.”

Despite his power, Armas heard some boos from Red Sox fans because of his anemic .218 average and 131 strikeouts in 145 games. “At that time, Latinos and black people were not beloved in Boston. I came to Boston and they started to boo me. I spoke with my lawyer and told him to get them to trade me. I didn’t want to play in Boston anymore. There was a pressure in playing for that team. They talked with me and said, ‘Hey, you came over here to help Jim Rice and Dwight Evans.’ ‘Yes, but I can’t, this way. It is very difficult to play like this.’ At that time it was different from the way it would be now – if I had been signed to a $120 million contract, I wouldn’t have cared if they shouted at me and booed me. But at that time you had to earn your place and play hard.”

A year later the Venezuelan, led by his power, changed those boos into ovations. Injury– free, Armas played 157 of the team’s 162 games and home runs steadily found their way into the stands. He finished as the American League leader in both home runs and RBIs (43 and 123). He dominated the circuit with 77 extra– base hits and 339 total bases.

“You never have those goals. Your goal is having a good year, but I never thought I would be the home– run king or the RBI champion when there were many superstars in the majors – Reggie Jackson, Jim Rice, Dave Kingman, Lance Parrish, Dwight Evans, many good players. That I could compete with these superstars made me proud, and that year, thank God, I was able to play an almost full season.”

Armas’s remarkable season earned him his second All– Star Game and his only Silver Slugger Award, and he placed seventh in the MVP voting.

Injuries cropped up again in 1985 and Armas was limited to 103 games; his production declined sharply to 23 homers and 64 RBIs.

In 1986 Armas got into 121 games as the Red Sox advanced to their first World Series since 1975. And if the defeat in 1975 was painful, after the famous Carlton Fisk homer in Game Six forced a deciding seventh game, the loss to the New York Mets was even worse.

“These were frustrating days for me,” admitted Armas, who was the greatest home– run hitter in the American League from 1980 through 1985, with 187 round– trippers, but he hit only 11 in 1986. “In the ALCS I hurt and I couldn’t play anymore, because my right ankle was swollen.”

If Armas’s home runs had seemed to become a constant in Boston, so had injuries. During his career he spent 12 stints on the disabled list, but no injury was as painful as the one in the fifth game of the ALCS against the California Angels at Anaheim Stadium.

In the second inning, Armas chased down a long fly ball hit by Doug DeCinces. “Many of my leg injuries were from running, but the one in the ankle was because I was hooked in the center– field fence,” he recalled. “Now they are cushioned but back then, the walls were all concrete.” Dave Henderson took over for Armas for the rest of the playoffs. Henderson had an immediate impact.

“I tried to play, but I couldn’t anymore,” Armas said. “And that’s when Dave Henderson replaced me and he did a good job.” Henderson’s ninth– inning homer in Game Five against Anaheim spared the Red Sox a loss, and he drove in the winning run with a sacrifice fly in the 11th. Though Armas’s ankle improved, Henderson made the most of his opportunity; Armas was sentenced to the bench.

In the World Series, Armas was limited to one pinch– hitting appearance in Game Seven, after 15 days without playing.

“The ankle still bothered me, but I could pinch– hit. I could not run at 100 percent,” he recalled. “It was difficult, but I had a strong desire to appear in the World Series. Even if it was just an at– bat, it doesn’t matter, and I appeared in the World Series, which is what anyone wants.”

Armas pinch– hit for pitcher Bruce Hurst in the seventh inning with the game tied 3– 3. The Venezuelan struck out swinging in what it was his last at– bat in a Red Sox uniform.

About Game Six, he was philosophical. “What happened is what happens so often in baseball. We were winning an easy game. At the end we felt champions but Bill Buckner‘s error left us without the victory. Then we lost the World Series,” said Armas. “We lost by an error that cost us the Series. These are things that happen in baseball.”

“The pitching also faltered. Roger Clemens couldn’t do the job, Dennis Boyd couldn’t do the job, many players didn’t do the job,” he said. “For me it was frustrating because I was playing every day, but then I couldn’t help the team in the World Series because of an injured ankle. That’s not easy for any baseball player.”

After the season Armas became a free agent and, a likely victim of collusion, signed with the Angels but not until July 1, 1987. “The team owners got together and agreed to not sign free agents that year and I was one of those affected,” he recalled. “I had offers from Mexico, but spent all that time practicing in Caracas with Pompeyo Davalillo, who was working with the Angels at the time. That’s where I signed.”

After so much downtime, Armas was sent to Triple A for the first time in more than a decade. He played in 29 games for Edmonton before returning to the majors for the last month and a half of the season. He batted.198 in 28 games.

Armas’s days as a regular came to an end in California, where he was used primarily against left– handed pitchers by manager Cookie Rojas, with whom he had a difficult relationship in 1988. “I started to play against left– handed pitchers and that was hard,” he said. “There was a time when I began to play every day and in a week I hit like five homers – but that’s when I had the mishap with Cookie Rojas.”

“One day we went to Oakland to play and Chili Davis, who was the regular, did not want to play; people were booing him, because he’d played the year before with San Francisco. Oakland was going to start Dave Stewart and they said I was not going to play because I was playing against lefties only. Then I got a chance to start playing against some righties, and I hit two home runs in that game (August 14). Rojas didn’t put me to play anymore and there came all the controversy with the journalists, saying that if I was hitting well, why I did not play. He said it was because he was the manager, and I told them to talk to the manager, that if they did not play me, it was a matter of him.”

From July 28 to August 14, Armas hit.440 with 4 homers and 12 RBIs over a 16– game stretch, including 11 starts, so some sportswriters suggested more playing time for the Venezuelan, even against righties.

“There was this controversy with journalists and Cookie Rojas blamed me because I spoke with the press. Once a newspaper did an article and it was sent to him in Boston and I was called to his office and he asked me why I had told the newspapers that I wasn’t playing. ‘Look, Cookie, I haven’t talked to the press in a long time. They just are realizing what you’re doing to me.’ ‘So you want to play?’ And I got to play against Roger Clemens in Boston. I said, ‘Cookie, if you think you’re going to intimidate me because it is Roger Clemens, you’re wrong. If he was going to give me four strikeouts, I’ll get four strikeouts. If I’m going to hit him, I’ll hit him.’”

And Armas homered against Clemens (two days earlier he had hit one off Bruce Hurst), and then he hit another the next day, on his return to California, against the Yankees. It was Armas’s most explosive month of the year and his last major production in the majors:.386 with 8 homers and 19 RBIs in 24 games in August. Nevertheless, his differences with Rojas continued.

“It came out another article in California, after he took me out in a game for a pinch– hitter, even when I had a hit and a home run. I showered and went to the hotel. I did not talk to any journalist. When we got to California he called me to his office, and we hadn’t an argument, because I’m not used to that, but he said why I had talked again to the press. ‘No, no. I have not spoken to the press.’ But they were already realizing who he was.”

The relationship ended on September 24, when Rojas was fired as the manager of the Angels. Armas returned to the Angels the following year, his last in the major leagues.

“My third year in California was in the same role, as a pinch– hitter and playing against lefties, and because my knee was bothering me and I couldn’t take it anymore, I retired. I could have played for three more years, but unfortunately the knees did not allow it.”

Armas remained active in the Venezuelan Winter League, where he was already a legend for his power. He was the first Venezuelan to lead the majors in homers and RBIs, but his 251 career home runs led all Venezuelans. He was also the home– run king in Venezuelan winter ball, after hitting his 97th home run in the last at– bat of his career in the 1991– 1992 season. (His mark was surpassed by Robert Perez in 2008.)

Armas played a few more seasons in Venezuela, but the knee hampered him badly and he’d have to take off a week now and again. “I thought it was better to retire than continue to suffer, but I thank God for giving me the opportunity to get where I got. Thanks to baseball I am who I am.”

The home run was always Armas’s calling card; it also happened to be his farewell letter. He was an investor in the Caribes de Oriente club and he was able to fulfill another dream there, playing with his brothers Marcos and Julio, all three taking up positions as outfielders.

“That was a great thing,” Armas said. “It’s never been written in any book. I was with the right team on the right day.”

Both brothers followed in the footsteps of his older brother, but only Marcos managed to make the majors, with the Athletics for a brief period in 1993.

Tony and his wife, Luisa de Armas, had six children. The third was their son Tony Armas Jr., who played 10 major– league seasons with the Expos, Nationals, Pirates, and Mets, between 1999 and 2008.

“I have much to thank my dad for. Since my childhood he always took me to the stadiums. When you are a child you are like a sponge, absorbing all the information and always trying to imitate someone,” said Armas Jr. “When I decided to play baseball, he said to me, ‘I was a hitter, but if you don’t want to be a hitter, don’t do it.’ He told me, ‘Son, do what you want to do. I support you.’ That was important. My parents, at that time, supported me the most.”

After he stopped playing, Armas remained active in baseball, mainly in winter ball, as coach of the Caracas Lions. Tony Armas Jr. also played with the Lions. “That was special,” said Armas Jr. “It was one of the most special times. I grew up in the Caracas stadium of Caracas, because he always took me there when he played. He felt the same way.”

In 1998 Armas was inducted into the Caribbean Baseball Hall of Fame, thanks to his all– time home– run leadership in the Caribbean Series, with 11. In 2005 he was inducted into the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame and in 2013 into the Latino Baseball Hall of Fame. In 2009 Armas was the hitting coach for the Venezuelan team in the World Baseball Classic, working next to Andres Galarraga, who eclipsed all his home– run records in the majors. (In 1996 Galarraga hit 47 homers and drove in 150 runs with the Colorado Rockies to set the single– season marks for a Venezuelan.)

“Tony was a role model for all the boys that had power,” Galarraga said. “I was fortunate to sign with the Lions and privileged to play with him in Venezuela. He taught me many things, gave me some batting tips and that kind of thing.”

“I always knew that many good players would follow, because in Venezuela we had many academies and we had many players out there,” said Armas. “After Galarraga came Bob Abreu, who was a complete player, Magglio Ordonez, and now Miguel Cabrera, who is even more complete. There is always someone who opens the doors.”

And Armas, 62 in 2015, continued to share his knowledge with the younger generation in Venezuela, as a coach of Leones del Caracas (the Caracas Lions) in winter ball. “He loves to teach, because baseball is his life,” said Armas Jr. That’s never going to change with him. He ends a winter season and during the break goes directly to become a manager in the Bolivarian League with Deportivo Anzoátegui. He is always working with the boys and never stops. He’s always traveling; he is never in one place. That is what he likes to do.”

“Baseball has given me a lot. Now I’m giving to baseball, trying to help young people,” said Armas, who still lives in his native Puerto Píritu. “I am very proud of my career, proud of baseball, and proud of what I do right now, because in my time there were no hitting coaches and I’m proud to work with so many young boys to help them become better players.”

Sources

Author interviews with Tony Armas on November 12, 2014, and August 5, 2015. All quotations attributed to Armas come from these interviews.

Author interview with Andrés Galarraga on July 30, 2015. All quotations attributed to Galarraga come from this interview.

Author interview with Tony Armas Jr. on July 28, 2015. All quotations attributed to Armas Jr. come from this interview.

articles.latimes.com/1987– 08– 19/sports/sp– 773_1_tony– armas

articles.latimes.com/1988– 08– 25/sports/sp– 1345_1_tony– armas

articles.latimes.com/1988– 09– 01/sports/sp– 4439_1_home– run

articles.latimes.com/1988– 09– 24/sports/sp– 2381_1_interim– manager

el– nacional.com/deportes/lvbp/Antonio– Armas– puesto– acepte– recogebates_0_289171243.html

vidaydeportes.com/entrevista– exclusiva– antonio– armas

Cárdenas, Augusto. “El jonronero de Venezuela,” Diario Panorama, December 18, 2005.

Cárdenas Lares, Carlos Daniel. Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas (Fundación Cárdenas Lares, 1994).

Full Name

Antonio Rafael Armas Machado

Born

July 2, 1953 at Puerto Piritu, Anzoategui (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.