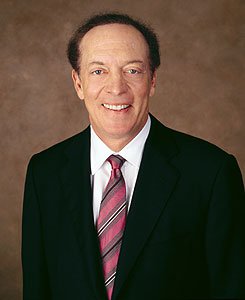

Dick Stockton

It is rare for a single moment to pivot a career. Dick Stockton is an exception, not rule. Before 1975, Stockton moved from Syracuse University via KDKA Pittsburgh’s revolutionary news to pro basketball’s Boston Celtics. After 1975 he aired a Klondike of more national sports, including the Red Sox, A’s, and network baseball postseason and weekend Game of the Week. The pivot was a magical baseball year – and game.

It is rare for a single moment to pivot a career. Dick Stockton is an exception, not rule. Before 1975, Stockton moved from Syracuse University via KDKA Pittsburgh’s revolutionary news to pro basketball’s Boston Celtics. After 1975 he aired a Klondike of more national sports, including the Red Sox, A’s, and network baseball postseason and weekend Game of the Week. The pivot was a magical baseball year – and game.

To be precise, the hinge was perhaps baseball’s greatest match – Red Sox-Reds World Series Game Six – climaxed by its greatest moment: Carlton Fisk’s 12:34 A.M. October 22, 1975, blast off Fenway Park’s left-field foul pole. “Its Midas Touch enriched me, the Red Sox, and above all, baseball,” said Stockton of the Sox’ 12-inning 7-6 wonderwork that tied the Series at three games each. Its quality of disbelief still exists, especially Dick calling Fisk’s showstopper on NBC Television despite barely airing baseball before 1975. It is a time worth recalling – and life worth retelling.

Stockton’s life began on October 12, 1942, as Richard Edward Stokvis, in Philadelphia. Moving to New York, his father, an advertising executive, bought season tickets to the Giants, whom Dick followed in his youth with metronomic regularity. The team’s home was the twin-tiered Polo Grounds, in a hollow 115 feet below Coogan’s Bluff. Polo was never played there: After 1890, baseball was. The park was even more asymmetrical than Fenway Park, Stockton’s future beau. Foul turf formed a vast semicircle behind the plate to each line. Roofed bullpen shacks anchored left-center and right-center field. Pee-wee foul lines earned the snarl “Polo Grounds home run.” Right field was 257 feet from the plate. A 21-foot upper deck overhang made left’s 279 feet seem closer. By contrast, center field’s 483 feet seemed rooted in another time zone. Its rear wall read 505.

As a boy, Stockton attended Forest Hills High School in Queens. By then, Dad had also bought his son’s first Bowman baseball cards: five in a pack. Junior’s favorite player, Red Schoendienst, was shown horizontally close-up, bat over shoulder, wearing a blue cap with red peak and intertwined STL. Stockton recalled spying “team pennants floating in the breeze, walking from the Speedway on Coogan’s Bluff,” and light towers atop the upper deck, like corn stalks in a field. Through the runway Dick eyed roofed bullpen shacks, a Chesterfield cigarettes sign, and batting practice, the visiting Cardinals in the cage. They wore a road uniform of gray with red numbers trimmed in blue, red stockings with blue and white stripes, and familiar St. Louis cap.

Two Redbirds had “one foot on a tire supporting the cage,” Dick said later, bright with memory: Number 6, Stan Musial, bats and throws left, born Donora, Pennsylvania, and especially his hero, Number 2, Schoendienst, bats switch, throws right, born Germantown, Illinois. “My card came alive,” Stockton said, especially on the road, studying his Giants yearbook’s aerial shot of each National League (NL) park as Giants announcer Russ Hodges noted Braves Field’s right-field “Jury Box” or Crosley Field’s “laundry” behind the left-field wall. Forbes Field denoted Schenley Park; Ebbets Field, the high wall in right. As a teen, Dick pined to be a sportswriter after being mesmerized by the sound of reporters filing from midcourt at Madison Square Garden. Yet it was “radio that was my friend,” said Stockton, “and creativity that was radio’s.”

Reality preceded the Syracuse Class of ’64 political-science major’s first baseball telecast. In 1965, the speech and dramatic arts specialist began at TV and radio outlets in Philadelphia. Two years later KDKA TV made Stockton sports director on its thrice-nightly Eyewitness News, “a first-of-its-kind idea, anchors and reporters speaking amid live newsroom chaos. When film or commercial ran, our police radio was turned on full.” In September 1969 Pirates skipper Larry Shepard was fired, his successor expected to be Don Hoak or Bill Virdon of the sainted 1960 world champion Bucs. On decision eve, Stockton repeated his on-air view that “Don’s personality was needed after Shepard’s quiet manner.” The next day at 5 P.M. retired 1960 Pittsburgh manager Danny Murtaugh was surprisingly rehired. Dick took a call from Hoak: “hurt, furious, wanting to come on and blast the Pirates.” Dissuading him, Stockton went live at 6.

Minutes later police radio reported that Hoak had been found dead in suburban Shadyside. Numb, Stockton said: “We have just found out a shocking and incredibly sad development. Don Hoak, who had been a prime candidate to become new manager of the Pirates, has died of a heart attack. Details to come on the 7 P.M. newscast.” After the 30-minute network news, he told how someone had tried to steal the car of Don’s brother-in-law. Hoak started his own auto, chased but never caught the other car, and was found slumped over the steering wheel at the bottom of a hill. Dick said that “to this day, Hoak’s wife believes that Don, who so badly wanted to manage the Pirates, died of a broken heart. Before broadcasting baseball, I endured a baseball tragedy.”

In 1971 Stockton moved to Boston NBC outlet WBZ, his coverage including commentary. In 1973 he left to freelance: Home Box Office cable TV, hoops Celtics, Baltimore Colts preseason football, and CBS pro football in-studio host. In 1974 he was phoned by Gene Kirby, producer of the mega-popular Dizzy Dean’s 1953-65 Game of the Week. “Gene had great stories,” said Dick, “since Dean was awful at pronouncing surnames.” Chico Carrasquel was “that guy with the three Ks in his name.” Italian and Polish runners occupied each base. “There’s a line drive,” Ol’ Diz said, “and here’s Gene Kirby to tell you all about it.” Boston’s new v.p., administration, told Stockton about a Red Sox TV play-by-play vacancy, then asked for an audition tape. The 32-year-old didn’t have one, his baseball vitae limited to 30 Indians HBO games in 1974. “So?” Kirby said. “Go to Shea Stadium” – the Yanks’ home as The House That Ruth Built was renovated – “record a game, and send me what you do.”

Dick thought Kirby would recommend him or say, “I wasn’t what Gene was looking for.” Instead, he again phoned, starting: “Got a pad?” Stockton took notes – “seven pages, back and front” – as Kirby lectured “from pregame to final out, the little I’d done right, the more I’d done wrong.” Tape again, Gene ordered, which six times Dick did, Kirby demanding that he “phrase correctly – baseball’s ‘patter’ – and properly inject things and describe plays.” After the seventh tape Kirby called to say “Eureka!” He could finally recommend Dick to the Red Sox. In 1975 Stockton said of Fisk, “Who could have predicted when I was enduring the grueling exercise of taping and being critiqued that one year later I would call such a play?” He wouldn’t have, without Gene.

At the time, Dick said, “I’ve always wanted to be an announcer for a major-league team because I think it’s the best job in sports broadcasting, and the Red Sox are the best team in the majors to cover.” He never changed his mind, always saying, “My time in Boston pivoted my career.” Such a trope seemed equally applicable to Stockton’s analyst, popular 1967-69 Sox slugger Ken “Hawk” Harrelson,” both crashing Hub TV amid change. For years, the club had “been stuck at 55 to 60 games,” said v.p./emeritus and team historian Dick Bresciani. “It’s all the inventory [programming] our flagship [WBZ] could handle. Network programming limited their freedom.” In late 1974, Hub UHF Channel 38 (WSBK) bought exclusivity for a 1975-1979 team-record $1.6 million a year. Non-network, it had more room in which to televise – 95 games by 1977.

“[Channel 38 G.M.] Bill Flynn told me he wanted to go with a new cast,” 1954-63 Indians and 1966-74 Red Sox play-by-playman Ken Coleman said in late 1974, soon returning to Ohio to televise the 1975-78 Reds. Harrelson replaced ex-Sox shortstop great Johnny Pesky. Some claim Harrelson beats his own drum. It is fairer to say he follows his own drummer. In 1969 Ken had been traded to Cleveland, saying, “Where else in the league is the lake brown and the river a fire hazard?” Bostonians picketed. Switchboards jammed. Said the Hawk, his nickname denoting an aquiline nose: “Baseball was never fun again.” In 1970 he broke a leg, took up professional golf, and found it his handicap. By November 1974, Ken had “thought about golf for months and that night decided to give it up.” At 3 A.M., panicked, he awoke: “What am I gonna’ do?” By quirk, Sox G.M. Dick O’Connell called that morning. “A year before he’d offered me TV color. How amazing was it to offer again when he didn’t know I was shucking golf?”

In new flagship WSBK’s first exhibition, Ken neatly navigated till Montreal’s Tim Foli’s single. “Feisty guy,” Hawk ad-libbed. “Lot of balls” – language then verboten in the public square. Stockton’s jaw dropped, even golf looking good. Harrelson found that Red Sox Nation is a forgiving, if not forgetting, lot. He also learned what worked. “Some guys, especially ex-jocks, coast on their names. Others numb you with statistics,” Ken said, having long ago inhaled “mama’s love of baseball,” his single mother in Savannah, Georgia, nightly listening with her son to the Cardinals’ KMOX Harry Caray. Like Stockton, Hawk never forgot, as Dick said, “To do your work, try for perfection,” finding that in New England even that might not be enough.

“Perfection” is not how 1974 ended for what Tigers broadcaster Ernie Harwell called “the Bostons,” the Red Sox blowing a seven-game late-August American League (AL) East lead. Never had a Boston team lost a title after leading by so much so late in the season. New skipper Darrell Johnson’s team stopped hitting, Reggie Jackson asking, “Who are all these Mario Andretti [infielder Mario Guerrero] guys?” Pitcher Luis Tiant, circa 33, allowed two or fewer runs in eight straight starts, winning once. The Boston Globe’s Leigh Montville wrote: “The Red Sox fan, of course, is mad mostly at himself. He had forgotten his inbred pessimism, his rooting heritage. He had stuffed it in a drawer.” Out it came, the Olde Towne Team placing third. Carl Yastrzemski led in average (.301), RBIs (79), total bases (229), slugging percentage (.445), and home runs (15, with Rico Petrocelli): each a 1960s and ’70s single-year club worst.

As they had and would again, the Sox eyed top affiliate Triple-A Pawtucket. Jim Rice, 21, became International League Most Valuable Player. Fred Lynn, 22, joined the Red Sox in September 1974. Dwight Evans was 22; Rick Burleson, 23; Fisk, 26. Still, Stockton said, “Few if any believed that young hopes of April [1975] would survive and become the young heroes of October!” They began in a northeaster – and before a Fens then-record first-day 35,343. In 1967 Tony Conigliaro had been hit by a pitch by Jack Hamilton, severely damaging the left eye. In May 1975 Tony C. tried a final comeback. “There’s a drive to left field!” Stockton said. “First [also final] home run by Tony C. since his comeback!” By Memorial Day the Sox were only 21-17. The Yankees arrived three weeks later, Fisk returning from a broken wrist. The Townies took the series, three games to one, and first place to stay. Fisk batted .331 and Cecil Cooper .311, Denny Doyle hit in 22 straight games, and Burleson steadied shortstop. Boston had only 134 homers, but led the AL in batting average, slugging percentage, and on-base percentage: “not a typical Sox club,” said coach Bobby Doerr. For one thing, they won.

Every fourth day Fenway said a rosary, congregants hymning “Loo-ie! Loo-ie!” as Tiant, finishing 18-14, left the bullpen before games and waddled across the field. Rick Wise was 19-12, Roger Moret 14-3, Bill Lee 17-9. Jim Willoughby and Dick Drago moored the pen. “The Red Sox always need pitching,” said Globe writer Peter Gammons. “In ’75, they had youth, too.” By June, youth’s name was Fred Lynn. On June 18 at Tiger Stadium, Lynn bashed three homers and had 10 runs batted in. To Sox radio’s Ned Martin, Lynn played center field like Frank Sinatra sang Cole Porter. At Shea Stadium, the Yankees’ 1974-75 halfway house, Lynn’s lunging final-out July 27 catch before a record Bronx Bombers crowd there (53,631) preserved a 1-0 Sox classic. The first same-year Most Valuable Player/Rookie of the Year wed a .331 average, 21 homers, and 105 runs batted in – an atypical Sox rookie.

Another unusual freshman was left-fielder Rice – to the media, with Lynn “the Gold Dust Twins” – so strong he broke a bat checking a swing. In July he became the sixth player to clear Fenway’s center-field back wall. Evans completed the best Sox outfield since Duffy Lewis, Tris Speaker, and Harry Hooper, saluted by “Dewey! Dewey!” Stockton felt Boston’s “right field the toughest in the game. You’d be racing that way, and boom, [the wall] caught you by surprise. It was short [three feet high] and you could hurt yourself, even fall into the stands trying to catch a homer.” Tougher was Evans’ arm: as Bugs Baer called Lefty Grove, able to “throw a lamb past a wolf.” One day the Sox faced a one-out, bases-full jam. “The heat is on,” said Dick. “Fly ball to right field to Evans. The throw to Carlton Fisk at home. Right on the money!” – two for the price of one.

After putting space between themselves and the Orioles and Yankees, the Red Sox began to lose in late August. Worse, the runner-up O’s began to win. Checking the calendar, Orioles skipper Earl Weaver vowed to “gain one game a week” on the Red Sox. On September 1 Baltimore columnist John Steadman likened the “Boston Chokers” to the “Boston Strangler.” A disc jockey for WFBR Baltimore flew to Nairobi to ask a witch doctor to apply a hex, the shaman getting $200 and two cases of beer. On September 3 a 2-all road game entered the 10th inning. With Jim Palmer still pitching, Cooper hit a ball deep to right field, where it hit over the wall, bounced back into play, and was called a homer. Sox win: 3-2. Eleven days later Lynn went 4-for-4, threw out Bobby Darwin at home plate, and clubbed his 21st and last regular-season homer: “Line drive, right field!” said Stockton. “If it stays fair, it’s a home run! It is!” Sox rally, 8-6, vs. Brewers.

“When Luis goes out there [Fenway], it’s just different than any other man,” said Fisk. On September 16 El Tiante faced Palmer, beating him, 2-0, as Pudge and Petrocelli homered: Sox led by 5½ games. Organist John Kiley played Stout-Hearted Men for Tiant. Looie! Looie! filled the ancient yard. It was among Luis’s greatest moments in his Red Sox suzerainty. The Magic Number, a mix of O’s defeats and Sox victories to eliminate Baltimore, fell to seven games, with 11 left to play. “We’ve crawled out of more coffins than Bela Lugosi,” blustered Weaver, still incorrigible, his door closing September 27, the Birds losing twice to New York a day after the Sox twice blanked Cleveland, 4-0. Boston won its first AL East title.

Next day the season ended, WSBK’s rookies noting how the last-month playing roster of 40, not the usual 25, made on-field rookies as much as results the thing. Ex-Alabama quarterback Butch Hobson and Ted Cox were “two fine-looking third-base prospects,” Dick said. Hobson got “a base hit to right” – his first – but struck out on a curve. “That old Uncle Charlie has given a lot of youngsters problems,” said Hawk, whom one writer accused of “doing for instant replays what the … [Boston] Strangler did for door-to-door salesmen.” The lineup rivaled the Junior Varsity. Bernie Carbo batted cleanup! — “he lines a single up the middle.” Indians first baseman Joe Lis homered: to Stockton, “with muscles bulging from his uniform, rammed it out of here!” By fan ballot Lynn won the Tenth Player Award, his prize a Buick. “I don’t have a car,” said the Californian, “so this’ll come in handy.” The game peaked when ex-jock Hawk caught a foul one-handed in the booth, as he had on the field. “With hands as bad as mine,” Harrelson reasoned, “I always figured one hand was better than two.”

Before 1975 Dick had barely called a game. Early on, some scored his lack of an easy rapport with Hawk – what Kirby called baseball’s “patter.” Each resented the critique. “Show me where I am wrong in a statement of fact, but don’t get into this stuff about a flow of conversation,” Stockton said angrily, adding, “Hawk was incredibly popular as a person,” but after a few weeks of trying to mesh, Kirby and Dick O’Connell had a meeting and the station asked, ‘What’s going on?’” The Sox meant tradition. Yet “Hawk’d just say what he wanted, he was new to TV, and I was new to baseball.” It took a while to fit. By mid-to-late 1975 they had begun to jell. Trained on TV, Stockton “was comfortable working with an ex-athlete analyst. Hawk got comfortable with me. We didn’t make big mistakes, the sponsors and club liked us, and we were smart enough to play within ourselves.”

Thirty years later, Stockton became arguably Fox’s best ball-and-striker. Harrelson aired the Red Sox through 1981 and later the White Sox for more than 30 years. More veteran, the 1975 TV team would have been less chastised. Another video problem was special to New England. “Sox fans, perhaps more than any other team’s, are dependent on radio,” the Boston Phoenix’s Michael Gee wrote. “The stations in their chain stretch from Woonsocket to Presque Isle, and there are uncounted Red Sox rooters for whom a trip to Fenway is an annual adventure.” The wireless fed small towns, back country, and burnt-orange hills. Like Dick, Ken knew the pecking order. “Much of the region is isolated,” he said. “No matter the announcer, radio’d be top banana.” This did not stop TV from trying to climb Red Sox Nation’s tree.

Stockton’s leading problem was something he could not control – Sox radio’s tandem. In 1974, ageless 58-year-old Jim Woods joined Martin, 50, Boston’s 1961- wireless virtuoso, to become, as the Boston Globe’s Mike Barnicle wrote, a “Tracy-Hepburn of radio, the Gable-Lombard, Hunt-Fontanne, Redford-Newman, Fielder and The Pops kind of combo that lend class and style to the phrases that describe the perils of our Olde Towne Team.” Each knew the game, played off the other, and refused to toot his horn. Stockton knew the odds. “Ned was as good a radio broadcaster as I’ve ever heard, and Woods complemented him beautifully,” Dick said. Novelist Robert B. Parker agreed, saying “Martin reminded us that baseball is a game of wit and intelligence. Woods kept alive our sense of wonder. Between them they were perfect” – at least as good as the Sox’ final 95-65 record, or 1975 attendance: 1,748,587.

In the last regular-season game Woods called Ned “Nedley” and Martin ribbed Woods about his ex-Bucs colleague Bob Prince’s booth as bar. “Did Budweiser sponsor you, or did you sponsor Budweiser?” Woods’s baritone was “literally whiskeyed,” said Ned, his Scotch-Irish tenor as old-shoe as a slipper. They lasted through 1978, at which time each was fired because their radio flagship wanted good company men – not good listening company. Till then the poet and peripatetic – Boston was Woods’s sixth team – were pares inter pares: Latin for “first among equals.” Could the 1975 Red Sox be baseball’s? On Closing Day 1975 few cared that Cleveland beat the Townies, 11-4. The six-year-old best-of-five prelude to the World Series, the League Championship Series (LCS), followed by the fall classic, were already on the mind.

Much later, when a campaign began to replace Fenway Park, former NBC and Red Sox Voice Gowdy said, “Keep it! Don’t change a thing!” Except for the Series final, a New Englander wouldn’t change October 1975. It is true that Boston’s LCS rival Oakland had just won its fifth straight AL West title, starred Reggie Jackson, Sal Bando, and Joe Rudi, and was favored to shrink the Sox. It is also true that the Sox had Ancient Mariners averse to tension (Yaz, El Tiante, and Rico) and a Kiddie Corps too young to know what tension meant (Lynn, Burleson, Evans et al; Rice, injured, missed postseason). On cue, Tiant opened, winning 7-1: “This was Looie’s place,” said Dick. “He made all of Fenway a participant, not spectator.” Reggie Jackson turned dance critic, terming Tiant “the Fred Astaire of baseball.”

A day later Yaz launched a fourth-inning net-detector – an out anywhere but the Fens. “There’s a drive to left field!” Stockton said. “Going back! Looking up! Good-bye!” For variety, in the seventh we turned to Poss: “Fly ball, left field! … And Rudi will watch it go into the screen for a [Petrocelli] home run! Boston leads, 5-3, and Fenway Park is an absolute madhouse!” The two homers U-turned the series. In Oakland, Yaz, playing left field for the first time in several years, nabbed one third-game runner and kept another from the plate. “Carl makes another diving stop,” said Dick, “this play off Reggie Jackson.” A 4-3 groundball ended the Townies’ 5-3 sweep. “Doyle throws to first! It’s over! The Red Sox win the pennant! The Red Sox – no one gave a plug nickel for their chances in the spring – they defied everyone – they won the division title – a team that never gave up.” Yaz hit an LCS-team-high .455. The calendar could have read 1967.

By 1975, after a half-century of domination by great baseball cities like New York and St. Louis, baseball’s best teams, like Oakland, Pittsburgh, and Baltimore, had a K-Mart-like park, drew poorly, and played far from Manhattan’s creative colony. In the next 12 years, the Red Sox played three of arguably the five best games of any age: Game Six of the 1975 World Series; 1978’s playoff against the Yanks; and Game Six of the 1986 Classic. (Other contenders include Bobby Thomson’s shot and Bill Mazeroski’s walk-off.) Never before had the Republic seemed so affixed to the Boston American League Baseball Company. “The Red Sox by themselves didn’t save the game,” said Commissioner Bowie Kuhn. “They did, however, help,” starting now.

A common thread of the era is how Boston’s Voices deemed baseball less slam-bang than ballet. Stockton used statistics frequently, but effectively. Harrelson became a Southern-fried TV analyst, Hawkspeak his forte. Martin and Woods eclipsed even Rowan and Martin. A Boston hue colored most of the 1975 Series radio/TV – the last before the new ABC-NBC pact split regular-season, All-Star Game, LCS, and World Series coverage. The new pact also ditched partly localteams for just network mikemen. NBC had done Series TV and radio since 1947 and 1957, respectively. “With NBC, I had a chance. The new pact gave me none. Prior to the networks taking over in ’76, I snuck in under the wire,” Martin said, making the World Series at 51.

The 1975 Reds-Red Series walked a high wire. “The action took me along for the ride,” said Stockton, turning 43. Aiding Ned and Dick: Curt Gowdy, Boston’s 1951-65 prosopopoeia; Cincinnati radio duce Marty Brennaman, whom the Sox almost hired in the 1980s; Joe Garagiola, NBC play-by-playman and Cardinals catcher who got four hits at Fenway in Game Four of the 1946 Series; and NBC analyst Tony Kubek, serving as a “rover.” Had Cincinnati added TV Voice Ken Coleman, four of seven would have had a Townie tilt. As it was, three of six did, the Sox refusing to drop Martin or Stockton, respectively, on radio and TV. Each team’s Voice worked at home, Ned and Dick sharing Games One, Two, Six, and Seven at Fenway.

The night of Boston’s LCS clinching, the team took a red-eye flight home. By then, NBC executive Chet Simmons told O’Connell of the new broadcast arrangement. “As a kid the Series meant so much,” said Stockton, “and now to do one – imagine.” Leaving Oakland, Dick’s plane seatmate asked if he had a legal pad. Stockton said yes. “With that,” Dick said, “Hawk gave me a briefing for the next five hours on players from the Red Sox and Reds I could never get elsewhere. Not just basic stuff but nuance, strengths and weaknesses, inside dope,” Dick laughed, “like listening to a big-league Bible. By morning, arriving home, I’d graduated from Hawk’s Doctoral School of Baseball – a terrific boost to my self-confidence. I knew the Series.”

Before Game One at Fenway, Dick recalled the 1954 opener at the Polo Grounds, “immortalized by Willie Mays’s great catch off Vic Wertz and Dusty Rhodes’s game-winning tenth-inning homer,” Dad and son playing hooky from job and school, respectively, sitting eight rows behind the Indians dugout. The Series lured scribes, celebrities, and baseball royalty: bigger than Ike, brassier than Milton Berle, bonnier than Our Miss Brooks. America “stopped to pay attention,” wrote Heywood Broun, to Gillette’s Blue Blades March (“Da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da”), Sharpie the Parrot (“Mister, how ya’ fixed for blades?”) and voice-over (“Look sharp. Feel sharp. Be sharp.”). Connie Mack wore a high-starched collar. Yanks skipper Casey Stengel finally had a Series to watch, not win. Tallulah Bankhead and George Raft held court. Photographers snapped pregame pictures, Stockton Sr. saying “Do you know who that gentleman is sitting behind you? Douglas MacArthur. They think you’re his son.” Only later did fils grasp how the game “proved baseball’s unpredictability. Rhodes hit a 257-foot homer; Wertz, a 460-foot out.”

Cincinnati’s 1975 All-Star team included Hall of Famers Sparky Anderson, Johnny Bench, Joe Morgan, and Tony Perez, should-be Dave Concepcion, and once-cinch Pete Rose. None helped: El Tiante, 6-0. Next day Boston led, 2-1, when a rain delay broke Lee’s seventh-inning rhythm: Reds, 3-2. For a time Game Three was as drab as Cincy’s Riverfront Stadium: Reds, 5-1. In the ninth, Evans hit a two-run homer to tie the score at 5. Next inning Cesar Geronimo raced from first to third base when Fisk threw away Ed Armbrister’s bunt. “Armbrister interfered [with a forceout]!” screamed Johnson. Plate umpire Larry Barnett answered, “Forget it!” unlikely when Morgan’s hit won the game. A day later Tiant used 163 pitches to throw a 5-4 complete-game victory. Game Five was Don Gullett’s, pitching, and Perez’s, dinging twice: Reds, 6-2.

Ending there, the Series might be as dimly recalled as, say, 1950’s Yankees-Phillies. Instead, play returned to Boston, raining for three days. Some felt the delay would curb interest. In fact, it upped pressure – e.g., October 21-22. “Writers said, ‘Let’s end this,’” said Stockton. “The Series felt like it’d gone on forever. What helped is that Game Six was days after any action, therefore, had the spotlight, whether dud or masterpiece.” Lynn stunned the first-inning crowd with a three-run titan: Sox, 3-0. The Reds tied, then led, Dick thinking, “It’s over. Boston’s blown the lead.’” Behind, 6-3, in the eighth, Lynn singled, Petrocelli walked, and pinch-hitter Bernie Carbo barely tipped a foul. He then drove a parabola. Future Commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti later caressed “the evening, late and cold … the sixth game of the World Series [as] perhaps the greatest baseball game played in the last 50 years, when Carbo … uncoiled.” Gowdy’s TV play-by-play: “Carbo hits a high drive! Deep center! Home run! [booth silence for 15 seconds] Bernie Carbo has hit his second pinch-hit home run of this Series! That was a blast up in the center-field bleachers. It came with two out. … And the Red Sox have tied it, 6 to 6!”

Before Game Six, NBC Sports head Carl Lindemann, aware of Gowdy’s familial past with the Red Sox and that his network would next month drop the Wyoming Cowboy from baseball altogether, told Stockton, “Look, we want Gowdy to finish the game” – possibly Curt’s last big-league telecast after a decade as baseball’s network face and sound – “which means you go first.” Before 1976 each home-team mikeman did 4½ innings of a Series game. At the end of the tie game, Gowdy could have asked to do each extra inning. Instead, the Cowboy said, “Dick, let’s alternate on TV. You do the tenth inning, I’ll do eleventh, you the twelfth, and so on.” It was as kind as Gowdy’s introduction in Game One. “Curt gave me a sendoff that was beyond any expectations – ‘Boston fans love this guy’s work.’” To Stockton, “both as a person and behind the mike, Curt Gowdy is the greatest broadcaster of all time.”

Inning by improbable inning, narrative unwound. In the ninth inning, Lynn hit a none-out bases-full pop to left field. Third base coach Don Zimmer told the runner, Denny Doyle, “No, no!” Doyle thought Zim cried, “Go, go!” Gowdy, who had seen it all, hadn’t: “Here’s the tag. Here’s the throw! He’s out! A double play! George Foster throws him out!” In the 11th, Morgan pulled a one-out, one-on drive to right – a sure triple or home run. “Back goes Evans – back, back! And … what a grab! Evans made a grab and saved a home run on that one!” Curt said. Stockton found the see-saw “heart-wrenching to watch, impossible not to. The nerves, the back and forth. Evans throwing to [first baseman] Yaz [after his great catch for a double play]. So much at stake, so magnificent.”

Midnight came, and left. At 12:34 A.M., Fisk drove Pat Darcy’s 12th-inning pitch toward Fenway’s Green Monster. “NBC had opened a wonderful door for me when it named me to TV on the Series,” Stockton later said. Now, fixated, he said: “There it goes! A long drive! If it stays fair! … home run!” Martin had referenced “numerous heroics tonight, both sides,” then Darcy’s “delivery to Fisk. He swings. Long drive, left field!” Fisk employed hand signs and body English to push or prod or pray the ball fair. It caromed off the pole. Ned: “Home run! The Red Sox win! And the Series is tied, three games apiece!” Gowdy added: “Carlton Fisk has hit a one-nothing pitch. They’re jamming out on the field! … And the Red Sox send the World Series into Game Seven with a dramatic 7 to 6 victory! This is one of the greatest games in World Series history.” In 2003 Stockton told the New York Post’s Andrew Marchand that Fisk’s blast remained “easily the broadcast highlight of my life.” A decade hence he said: “It would have been nice to have a rhapsodic call, but there wasn’t time, just incredible doubt about whether the ball was fair. You had a split-second and had to get it right,” recalling “I was totally in the moment.” The moment has lasted 40 years.

Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis was 4 when he saw his first Fenway game in 1938. For Game Six in 1975 he and wife Kitty sat along the third-base line. “Things looked so bleak,” he said. “Then, out of nowhere, Carbo hits that blast.” They left Fenway thinking that “win or lose Game Seven, we’d seen one of the great games ever.” John Kiley began to thump “The Hallelujah Chorus.” Streets around Fenway heaved. In Beijing, nearly 11,000 miles away, it was Wednesday noon. George H.W. Bush, then envoy to China, and the embassy staff “cheered as Fisk’s homer cleared the wall.” Sparky Anderson sleepwalked to his hotel. Next night Boston led Game Seven, 3-0, till Rose upended Doyle on a probable sixth-inning double play. After Fisk ordered a curve, Bill Lee threw a blooper that Perez must have orbited: 3-2. In the 3-all ninth inning, Darrell Johnson inexplicably relieved Jim Willoughby for rookie Jim Burton, who forged a game-ending run more redolent of Deadball than the Big Red Machine. Ken Griffey walked, was sacrificed, advanced on a groundout, and scored on Morgan’s Series-winning lob. Yaz made the final out. Burton pitched one more big-league game.

Martin called Game Six “a keeper,” luring 66 million viewers – A.C. Nielsen’s fifth-rated all-time sports TV audience. It was a changer, too. A night later a then-record 75,890,000 watched, presaging the first all prime-time Series in 1985. Fisk topped TV Guide’s 1998 “Fifty Greatest Sports Moments”: “Every little boy who has ever played on a sandlot has dreamed of winning a World Series game with a last at-bat home run. … In short, do what … Fisk did. As if in a trance, the catcher bounced up and down near home plate, waving at the ball, willing it to stay fair. And when the ball obeyed, he leaped into the air and began his trot around the bases, both fists raised – just like a kid on the sandlot.” Fisk’s haymaker introduced the reaction shot, changing sports coverage. “Since then,” said famed NBC producer Harry Coyle, “everything accents people’s response to the play.” Lou Gerard’s camera had been inside the Wall, “my task, no matter what – follow the ball. As Fisk swung I saw a rat four feet away. I didn’t dare cause harm by moving, which is what I’d have had to do to shift the viewfinder.” By accident, the lens stayed on Fisk.

A week after the final pitch the Pirates ended the 28-year reign of Bob Prince, the King of Pittsburgh Baseball. Given his Steel City past, Stockton seemed a natural successor. “The only way I’ll leave the Sox is if they fire me,” Dick said, denying it. The Series had elevated him, buoyed freedom to leave or stay. At Fenway, change arrived, some unwelcome. “In the Series Lynn hit the center-field concrete wall and crumpled to the grass, the whole park quieting,” said Peter Gammons. In 1976 Sox owner Tom Yawkey padded the outfield fence base, replaced the Wall’s tin façade with plastic, shrank the board by dropping NL scores, and moved it 20 feet to the right. An enclosed press box rose. Up went a center-field ad message board. Jim Rice was the sole Townie to hit 25 homers. That July 9, Yawkey died, changing the immutable. Suddenly, it felt like being told that the Pilgrims landed at Bayonne. Changeless was the end: The Red Sox lost. As in 1947 and 1968, Boston in 1976 found defending a title harder than winning it. “With the talent we have on this club,” said Yaz, “playing .500 [83-79] is a disgrace.”

“We need pitching!” Number 8 chimed in 1977. Ferguson Jenkins’s 3.68 earned-run average led the staff. In exquisite irony, reliever Sparky Lyle, traded by Boston to New York in 1972, won the Cy Young Award, helping New York edge the Townies by 2½ games. By contrast, Boston’s punch sired records as varied as New England foliage: a major-league 33 homers in 11 straight games; another record five or more home runs in eight set-tos; on July 4 tying a big-league record eight homers in a game. On a three-game weekend in the Fens in June 1977, the Sox clubbed 21 homers off Yankees pitching, including four straight homers vs. Catfish Hunter. Twice Boston hammered Jim Palmer for five dingers. The “Crunch Bunch” hit a team-record 213 home runs; set 12 home-run marks, and tied 70 more. A year later brought “the apocalyptic Red Sox collapse,” said the Globe’s Dan Slaughnessy, “against which all others must be measured.”

In every sense, ’78 became a term that stood alone, needing no embroidery. Boston took first place in May, leading New York by 14 games in July. To Jackson, “if the Sox keep playing like this, even [racing’s Triple Crown champion] Affirmed won’t catch them.” The Yankees aped contender Alydar – until the Townies reached the backstretch.. In early August, the Sox lead dripping like a faucet, the Globe’s sports TV critic, Jack Craig, wrote a column or hit job, depending on your view. Titled “Stockton’s eternal optimism is getting deadly dull,” it termed Dick “a homer,” not unusual except that “Stockton seems so sincere about it.” Boston’s Frank Duffy’s “nervous hands and rainbow tosses were blamed on his inactivity.” Bill Campbell’s arm “that left no lead safe was treated as a twinge.” As bad, Craig said, Dick “never shuts up,” citing a sea of disconnected “players’ ages, minor-league credentials, high-school achievements, who was involved in trades, and assorted items that pass for coincidence and irony.” Each, the critic mused, showed proof of Dick’s coming late to baseball, “insensitivity to [its] timing.”

All week letters flooded the newspaper, creating “The Dick Stockton Issue” in the next Sunday’s Globe. One reader termed “criticism long overdue.” Another: “Dick Stockton should stick to basketball. Martin or Woods, or the Hawk alone, do your job much better.” By contrast, a Portsmouth, New Hampshire, reader said Craig should have attacked the Hawk: “Harrelson is the one who bores me out of my skin.” From Kittery, Maine, a Stocktonphobe dubbed “his bias abominable.” Locally, a Dick defender called him “the best baseball announcer in the country.” To a Plymouth resident, he was not as sturdy as its Rock: “[Craig’s piece] was a scathing review, but … impersonal, professional, and, to my mind, totally accurate.” In four years in Boston, Stockton had become a neutral-free zone.

Dennis Eckersley and El Tiante finished 20-8 and 13-8 with a top-five-AL-ranked 162 strikeouts and five shutouts, respectively. Jim Rice was voted MVP: 46 homers, 139 RBIs, 15 triples, 213 hits, .315 average, and 406 total bases, a wrecking machine and Renaissance Man. “They talk about leading by example,” Stockton said one day. “The captain, Carl Yastrzemski, 39 years old, playing in left-center field, chased a ball that seemed certain to be an extra-base hit and a run” because the Yankees’ Thurman Munson had been running on the pitch and the wind propelled the ball to the corner. “Yaz took off, caught the ball, braced himself against the Wall, and threw the ball quickly toward first,” amazing everyone by doubling Munson. Unlike much of the club, Yaz seemed immune to overuse and injury.

Before long the 1978 Red Sox braved a 2-8 road trip; then, a Boston Massacre vs. the Stripes, losing a first-place lead, 15-3, 13-2, 7-0, and 7-4; meanwhile, a 3-14 September swoon in which Boston fell 3½ games behind; then perversely won its final eight. On closing day the Sox had to beat Toronto to force a one-game AL East playoff in the Fens. “Here it is!” Stockton said of Luis Tiant’s last game in a Boston uniform, blanking Toronto, 5-0 – “ Jack Brohamer in foul territory! We go to tomorrow!” – game No. 163, against the Yankees: combat the hard, which was the Red Sox, way. “As the[ir] broadcaster, you woke up screaming in the middle of the night,” Dick said in 2003. “But enough time has passed that now I’m much calmer.”

In the second inning of the playoff Dorian Gray faced New York’s Ron Guidry: “Drive to right field! This is deep! And this ball is gone! A home run by Yastrzemski!” said Stockton. The noise was insupportable. Hawk added: “God bless him. This man is unbelievable.” Soon up, 2-0, Boston starter Mike Torrez faced Bucky Dent in a two-out and two-on seventh. “A drive toward left!” said Woods, like Stockton doing his Sox finale. “Yaz will watch it go into the Screen and the Yankees lead, 3 to 2! … Suddenly, the whole thing is turned around!” In the ninth, behind, 5-4, Yaz faced the Yankees’ Goose Gossage: again two out and two on. “And he pops it up! Graig Nettles at third base, backs up!” said Dick. “He makes the catch, the Yankees have won the division, beating the Red Sox, 5 to 4, in a game that will go down in history as one of the most heroically hard-fought games ever.” Yaz’s fly had ended the 1975 Series. His pop now ended the playoff with the tying run on third and winning run on first. In the clubhouse Yaz wept. That month Stockton joined CBS-TV, having tutored Harrelson and learned baseball’s “patter.”

“Stockton leaves for CBS and $825,000,” the Boston Globe headlined. Jack Craig’s column had a lovely Nixonian twist: “We won’t have Dick Stockton to kick around much longer.” Stockton’s four-year contract would reprise his role as host of Saturday’s Sports Spectacular, interviewing big names, updating events and scores, and winging it on the fly – akin to his 1974 period at CBS. “Stockton made an impression that lingered at CBS,” wrote Craig. An official there praised Dick’s skill “for finishing on the precise second [for commercial].” Having recently bought a home in Boca Raton, Florida, near Yastrzemski’s, Stockton seemed a natural. Some spoke of his becoming CBS’s Jim McKay – his network’s in-studio star. Instead, Dick bloomed at 1978-93 pro football and 1981-90 pro hoops, leaving Boston at a confusing time to be a Red Sox fan.

Released from a final year of Reds TV, Ken Coleman retook the Logan shuttle in 1979 to his boyhood park in the Fens, many expecting him to again man Sox video, replacing Stockton, who had replaced Ken in Boston after 1974. Instead, Martin, who hated the kinetic tube, succeeded Stockton, who didn’t. Surprisingly, Coleman assumed Ned’s roost on radio. In 1983 Stockton married Globe writer Lesley Visser, whom he had met at the 1975 Series. Their marriage lasted into 2011. Visser became the first woman inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. Dick and baseball also drifted apart. “You tend not to follow a sport you don’t cover,” he said. Ultimately, coming full cycle, Stockton rejoined the sport that in October 1975 had galvanized his career.

In 1990 CBS bought Game of the Week. Unlike weekly on-the-air predecessor NBC, CBS aired 16 Games in a 26-week season. Through 1992 Dick and Jim Kaat forged its No. 2 team. In 1994-95, Stockton was spared the junky The Baseball Network. Instead, he did basketball, including the NBA on TNT for more than a decade, getting a play-by-play Cable ACE nomination and joining the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame. In 1985 he voiced Villanova hoops’ upset of Georgetown; 1991, won the Curt Gowdy Electronic Media award from the Basketball Hall of Fame; 2001, joined the Hall. Football: After 38 years as an NFL carrier, CBS lost rights to Fox in 1994. That year Stockton joined Fox’s rookie coverage with analysts like Matt Millen and later Troy Aikman. One year Dick did hockey; another, the Pan American Games in Caracas, Edmonton, or San Juan; another, the world swimming and diving and world figure-skating championships; in 1992, the France Winter Olympics, including alpine skiing; in 1994, the Norway Games, featuring speed skating gold medalists Dan Janssen and Bonnie Blair – for Dick, the complete package.

Still, he missed baseball. In 1993-95, Stockton did Oakland A’s TV. Then, in 1996, Fox bought big-league exclusivity – like CBS, airing it on the cheap: 16 Saturdays in 26 weeks. Coverage began near Memorial Day, stopped after Labor Day, and virtually vanished during a pennant race. This let Fox’s No. 1 baseball Voice Joe Buck at least keep his football schedule. In 2003 Dick became lead announcer of Fox’s backup team. In 2007 baseball’s sole network finally kept Commissioner Bud Selig’s decade-long vow to air Game each Saturday. “I think I’m destined [only] for 10 more years in baseball,” said Buck, in some years missing almost as many Games as he worked. Feeling that you should show up to earn a salary, Dick was received far better than before Fisk swung, “a fine broadcaster not elicit[ing] many opinions one way or the other,” said the Los Angeles Times’s Larry Stewart. “He just quietly goes about his business without drawing much attention to himself.”

From 2007 to 2013, Dick also anchored Fox’s postseason Division Series. Then, in 2014, the network’s new contract took effect. Fox cut its coverage to 12 Saturday games, renamed them Baseball Night in America, and put a young ensemble cast around Buck. Fox Sports 1 Cable, the network’s new cable offshoot, got rights to 40 Saturday games. Approachable and very knowledgeable, Stockton was inexplicably assigned largely to other sports, leaving June 12, 2010, as perhaps his best Fox baseball memory. In the lead Game of the Week, Boston hosted Philadelphia in ex-Santa Clara University team equipment manager, minor-league journeyman, and 27-year-old Sox rookie Daniel Nava’s first game.

Stockton, then 68, was Fox’s play-by-play man, the Red Sox continuing to form a vine around his trellis. Before the game Boston radio Voice Joe Castiglione suggested that Nava “swing on the first pitch, because you only get one chance.” In a bases-full second inning, the modern-day Joe Hardy did, amazing Stockton, 37,061 at Fenway Park, and doubtless Nava himself by pulling Phillies pitcher Joe Blanton’s pitch into the Red Sox bullpen: only the second big-leaguer to hit a grand slam on his first big-league pitch.

Learning of his call-up that day from Triple-A Pawtucket, Daniel’s parents had almost missed a flight to see him play. “I told the girl at the desk that my son was going to be playing left field in Boston, in front of the Green Monster,” said Don Nava. “They had to get us on,” and did. In the stands, camera flashing, dad’s and mom’s Kodak moment was captured by Game of the Week. As Nava entered the dugout, the magic moved Stockton, who, likely recalling 1975, said “There’s just something about Fenway Park.” You could say that about our friend behind the microphone, too.

Last revised: October 13, 2014

Sources

The vast majority of this biography’s material, including quotes, is derived from my books Voices of The Game: The Acclaimed Chronicle of Baseball Radio & Television Broadcasting – From 1921 to the Present (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); Our House: A Tribute to Fenway Park (Chicago, Masters Press, 1999); Voices of Summer (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2005); The Voice: Mel Allen’s Untold Story (Guilford, Connecticut: The Lyons Press, 2007); Pull Up a Chair: The Vin Scully Story (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2009); and Mercy! A Celebration of Fenway Park’s Centennial Told Through Red Sox Radio and TV (Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2012). The magazine Diary of a Winner 1975: Play by Play and Day by Day, published by Shamrock Publishing Co., Boston, was also helpful – a game-by-game diary of the 1975 Red Sox. In addition to newspapers cited in this article, I listened to audio and saw video supplied by noted broadcast expert Tom Shaer, president of Tom Shaer Media, Inc. Wikipedia was a valued source for Dick Stockton and the 1975 Sox. Bill Francis of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum was a final authority for statistics and other facts. I interviewed Stockton on August 8, 2014, for 90 minutes. His voice and enthusiasm denote preternatural youth. Other personal interviews, some with principals now sadly gone, made this a better story: Joe Castiglione, Jack Craig, Curt Gowdy, Ken Harrelson, Ned Martin, and Larry Stewart.

Full Name

Richard Edward Stokvis

Born

October 12, 1942 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.