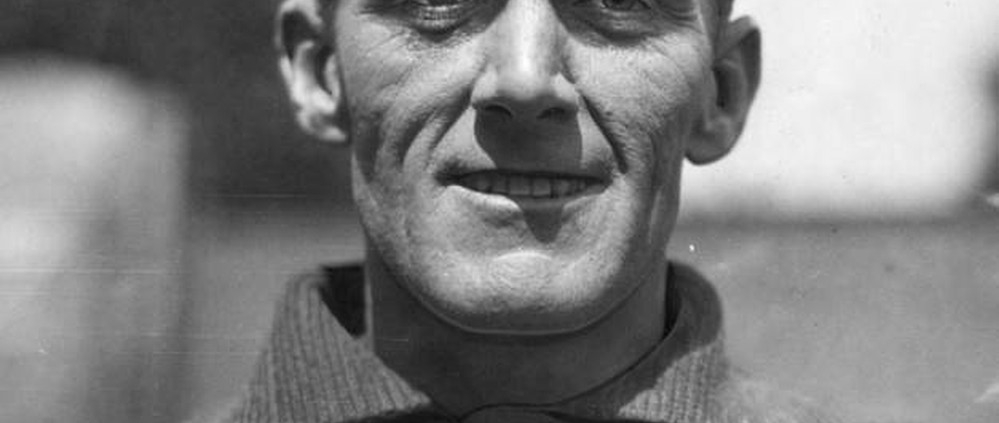

Clyde Barfoot

Former Army drillmaster Clyde Barfoot, a tall, husky, brown-haired and blue-eyed pitcher, relied on a “twisting fadeaway” called a “screw ball,” much like Christy Mathewson before and Carl Hubbell after him.1 His three seasons in the majors were sandwiched around his most successful professional campaign, winning 26 games in the Pacific Coast League in 1925 for a last-place team that won only 80 (against 120 losses). Barfoot stayed in top shape to toe the rubber well into his 40s, logging over 4,300 career minor-league innings, before moving out west permanently and becoming a Hollywood studio cop for the stars. But Barfoot might best be known as a footnote to the events of April 2, 1931, when he vacated the mound in favor of a 17-year-old female lefty named Jackie Mitchell, who, in a publicity stunt, proceeded to strike out both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Former Army drillmaster Clyde Barfoot, a tall, husky, brown-haired and blue-eyed pitcher, relied on a “twisting fadeaway” called a “screw ball,” much like Christy Mathewson before and Carl Hubbell after him.1 His three seasons in the majors were sandwiched around his most successful professional campaign, winning 26 games in the Pacific Coast League in 1925 for a last-place team that won only 80 (against 120 losses). Barfoot stayed in top shape to toe the rubber well into his 40s, logging over 4,300 career minor-league innings, before moving out west permanently and becoming a Hollywood studio cop for the stars. But Barfoot might best be known as a footnote to the events of April 2, 1931, when he vacated the mound in favor of a 17-year-old female lefty named Jackie Mitchell, who, in a publicity stunt, proceeded to strike out both Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig.

Clyde Raymond Barfoot was born on July 8, 1891, in Richmond, Virginia, the youngest of five children born to John Edward “Jeter” Barfoot and Annie M. (Beattie) Barfoot. Jeter passed away when Clyde was five years old. Although Annie didn’t die until much later, young Clyde and his brother Leslie, three years older, soon began to attend the Male Orphan Asylum School.2 One may assume that financial hardship was the reason – the Asylum’s charter allowed widows to request that their children be taken in.3

The brothers faced each other as opposing pitchers for two Orphan intersquad teams in 1906, with Leslie’s squad besting Clyde’s, which struck out 18 times.4 Clyde never attended a formal high school. By 1907, he worked as a saddler. Another brother, Clarence, six years older, also pitched in local amateur ball. Clyde played in the Richmond city league.

In March 1911, Barfoot enlisted in the Army, becoming a drill instructor at Fort Slocum, New York. He played right guard on their football squad,5 and semipro ball for a team in nearby Tarrytown. In August 1913, the right-hander was turned over by semipro manager Eddie Doyle to Connie Mack and the Philadelphia Athletics. Doyle predicted “that the pitcher will be a real find. Connie will try out the new twirler in New York tomorrow, when the Mackmen play the Yankees.”6 No record is found regarding an actual workout with Mack. Barfoot later received an offer from Baltimore of the International League before agreeing to join the Chattanooga Lookouts of the Class A Southern League, a surprising jump for a player who had never played in Organized Baseball.

New Chattanooga manager Harry “Moose” McCormick disclosed that “this Barfoot lad was recommended to me by a Brooklyn newspaper friend, whose judgment I have always found to be reliable. He is a tall, husky built fellow and ought to stand all sorts of work.”7 Lookouts President O.B. Andrews even successfully solicited the help of his congressman to sway the War Department for a release three weeks early for Barfoot, who by this time worked in a Baltimore commissary.8

An article reported that the six-foot, 170-pound “soldier-twirler is husky and substantial, and if his pitching ability is on a par with his physique, he will be a winner.”9 Catcher Gabby Street was “a keen booster for the servant of Uncle Sam.”10 Barfoot made the opening day roster for the Lookouts and won his first professional assignment on April 16 with a complete game victory over Memphis. However, in his next outing, in relief against Nashville, “Private Barfoot found it just as hard to dodge base hits as bullets and probably wished that he was down in Vera Cruz.”11 Chattanooga soon optioned Barfoot to the Galveston Pirates (also dubbed the Sand Crabs) of the Class B Texas League.12 Barfoot posted a credible 14-8 mark for fourth-place Galveston and new Pirates manager Paul Sentell.

Chattanooga sold Barfoot outright to Galveston for 1915.13 He logged the second-most innings on the staff (253.1), and ended with a 12-13 mark, while collecting three shutouts. A tragic hurricane ravaged the city of Galveston on August 20, 1915, causing over 100 deaths, ruining the Pirates ballpark, and ending their season.

Returning to Galveston for 1916, Barfoot married Nellie (Nell) Bridewell, an Alabama-born bride whom he met in Texas, during an April team road trip in San Antonio.14 He threw a seven-inning, 2-0 no-hitter against San Antonio on July 16 in the nightcap of a doubleheader.15 He ended with a 19-16 record. Barfoot started with Galveston for the fourth year in a row in 1917. However, in May, the last-place Pirates disbanded, and Barfoot was awarded to the San Antonio Bronchos.16 His finished 1917 with a combined Texas League record of 19-13.

Back with the Bronchos in 1918, Barfoot won eight straight games through mid-June.17 He posted a 12-7 mark before the league ceased operations on July 7. Barfoot latched on with the Columbus (Ohio) Senators of the American Association. He pitched a 3-0 four-hit shutout over Indianapolis for the Senators in their final game of the league’s season on July 21.18 The schedule was truncated by World War I.

Barfoot next wandered further northeast, landing with the Newark (New Jersey) Bears of the Class AA International League for the final six weeks of the season. He nominally led the league in ERA (1.29) over 56 innings, to go with a 5-2 record.19 He spent the off-season working at a munitions plant.20

Starting his third year with San Antonio in 1919, Barfoot impressed in spring training during a six-game series against the St. Louis Browns.21 Unfortunately, as the season began, he was laid up in a hospital most of the first two months of the season, undergoing a groin operation in late April. Upon his return, he quickly rounded back into form, and wound up with a 9-8 mark. He worked in the Louisiana oil fields after the season.

Barfoot started 1920 back in “Santone” but was released in early May. He signed with the New Orleans Pelicans of the Southern Association.22 In his first game for New Orleans, he tossed a two-hit shutout over his former Chattanooga team, facing but one over the minimum.23 He won a 1-0, 13-inning victory over Tom Sheehan and Atlanta on July 18.24 Barfoot posted a 12-7 mark for the second-place Pels.

New Orleans traded Barfoot to the Houston Buffaloes for first baseman Roy Leslie before the 1921 season. Back in the Texas League (now designated a Class A circuit), Barfoot completed 33 of his 38 starts while going 22-13 for Houston, a St. Louis Cardinals affiliate. Cardinals scout Charley Barrett touted Barfoot, saying that he “looked like the best pitching prospect in class A company.”25 Barfoot had altered his delivery in 1921. He used to swing “his body around too far as he released his grip on the ball. He was smart enough to change his style so as to eliminate the cause of his trouble and the result was astounding.”26 After the successful season, he was selected by the Cardinals.27

In the Cardinals’ 1922 camp, Barfoot was labeled “another phenom St. Louis fans will find a gem of purest ray serene.”28 According to a nationally syndicated report in March, “Barfoot claims to have invented a new delivery for the especial benefit of left-handed batters. He calls it the ‘screw ball.’ It is described as a floating fadeaway which breaks in the same direction always, but drops at all sorts of angles out of reach of the hapless batters.”29 A later article discussed that “the ‘screw ball,’ a unique delivery, originated by Sergeant Barfoot, is his favorite resort to retire a batter, and he says it is more effective when used against a left-hand hitter. Leaving the hand before the arm of the pitcher is horizontal, it takes a sudden duck away from the batsman which generally produces the desired result.”30

Even if the delivery may not have been new, the descriptive term “screwball” may indeed have originated with Barfoot. According to the Dickson Baseball Dictionary, the pitch became known as a screwball after Carl Hubbell revived it in the late 1920s. The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers states, “We’re not sure…who named it.”31

St. Louis manager Branch Rickey surprised everyone by starting Barfoot against Babe Ruth and the New York Yankees in a March exhibition in New Orleans. Barfoot went six innings, allowing only one run and holding the Bambino hitless. Barfoot broke camp with the Cardinals and made his major-league debut on April 13, three months shy of his 31st birthday. He earned what would later be known as a save with 2 1/3 scoreless innings in the Cardinals’ win against the Pittsburgh Pirates.

After one start in April and 21 relief appearances, Barfoot made his second big-league start on July 5, a complete game victory over Cincinnati. Curiously, he made no more starts over his 42 total appearances. As credited retroactively, Barfoot led the National League in 1922 with six saves and 25 games finished. His record was 4-5 with a 4.21 ERA. St. Louis, which faltered down the stretch to finish tied for third place, was 12-30 in Barfoot’s 42 games pitched. A look at his game log indicates, however, that only a few of these games were blowouts.

Barfoot was recognized as the National League’s top hitting pitcher, being 11-for-25 (.440) as of early September.32 However, a 1-for-9 slump to end the year dropped him to a .353 mark.

Barfoot returned to the Cardinals for 1923. He was given the nickname “Coach” because he “used to sit behind (teammates) and second-guess while they were playing cards.”33 In his first start of the 1923 season, on July 8, following 16 relief appearances, Barfoot threw an eight-hit, 4-0 shutout against Burleigh Grimes and the Brooklyn Robins. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle wrote: “Clyde (Coach) Barfoot, a well-proportioned righthander, starting his first game of the season, was the kalsomine brush to the Superbas. He heaved up a well-distributed mixture of slants with which the hard-hitting Flatbushites could do nothing.”34 His next start six days later, at Philadelphia, was a disaster, with him giving up five runs in 1 2/3 innings. Barfoot was banished to the bullpen for the rest of the season.

Barfoot primarily entered games when his team was trailing. The fifth-place Cardinals were 5-28 in games in which he pitched. Critics claimed that Rickey misused Barfoot, historically a starting pitcher, during his two years with St. Louis.

In the offseason, Barfoot was sold back to Houston on his stipulation that the team “agreed to sell him to some major or Class AA club” after the season.35 In 1924, Barfoot went 19-12 for the Buffaloes. Thanks to his screwball, he pieced together a 27-inning scoreless streak in May.36 In late August, he belted two home runs, a double, and a single in a complete-game victory over Galveston, another one of his former teams.37 He had both an eight-game winning streak and six-game losing streak during the season. After the season, Barfoot was traded to the Vernon (California) Tigers of the Class AA Pacific Coast League for pitcher Alva Sellers and cash.

Barfoot enjoyed a tremendous year in 1925. The cooler coast was a godsend, away from the Texas heat. Barfoot posted a 26-15 record, leading the league in wins, over 354 innings for Vernon, a “hopeless tail-ender,” which finished in last place at 80-120.38 On October 15, Barfoot hit two home runs — his fifth and sixth of the season – and beat Los Angeles 5-4 in 15 innings for his 25th victory.39 . Before season’s end, Barfoot and Jackie Warner were sold to another club called the Tigers, the American League’s Detroit, for $35,000 and the rights to Dutch Leonard.40

After the season, Barfoot made the finals of the second annual professional baseball players’ golf tournament in Northern California, falling to Jigger Statz after defeating Pop Dillon in the semifinals. Barfoot also played for the Los Angeles White Sox in the Southern California winter league, losing to Bullet Rogan and a visiting barnstorming team of color, the Philadelphia Royal Giants.41

Detroit skipper Ty Cobb had been “battling a pitching dilemma for several seasons,” and thus was elated to bring Barfoot into the mix.42 He was labeled in spring training as “The New Claw in the Tiger Paw.”43 Also attending Detroit’s camp in 1926 was none other than fellow screwballer Carl Hubbell, in his first shot at the majors.

Hubbell – ordered by Cobb not to use his bread-and-butter pitch for fear of injury44 – did not make the Tigers squad. Barfoot did. One may only speculate as to why Cobb’s edict did not extend to him.

Sadly, a few weeks later, Clyde found out his mother Annie had died in Cleveland.45 Later that month, Barfoot, in his 11th and final appearance for Detroit, got “pounded” for eight hits and six runs over four innings against the Chicago White Sox.46 The next day, Detroit returned Barfoot to his former Vernon franchise, now the Mission (San Francisco) Bells.47 It turned out that the Tigers didn’t have much choice. As the story goes, when the Tigers purchased Barfoot and Jackie Warner, the contract of Dutch Leonard was turned over to Vernon. Leonard, however, refused the assignment. After much negotiation between Vernon and Detroit, Barfoot was forced to go back “to the league from whence he came,” although he had pitched decently for Detroit.48 He went 13-14 for the Bells; at the plate, in a mere 84 at-bats he hit seven home runs, good for third on the team.49. After the season, he played winter ball again, for the White King Soaps.50

Barfoot begrudgingly returned to Mission for 1927 after receiving a salary cut. Nonetheless, he led the league in innings pitched with 308 while yielding only 54 walks. After the season, Barfoot expressed a preference to be in southern California, so Mission traded him to Los Angeles. In 1928, Barfoot went 20-19 for Los Angeles, hurling 311 innings. The next season, he went 18-12.

Heading into the 1930 season, it was opined that Barfoot “looks like an old pappy guy – but the chap with the lean weather-beaten face may fool ’em considerable for another year.”51 As the Angels’ opening day starter for the third straight season, he beat new Coast Leaguer Carl Mays of Portland.52 Under his own byline, Barfoot observed that he had started 16 opening day contests over the years.53 He lost three weeks in the summer with a sore arm and posted only a 12-10 record.

After his six years in the PCL, Barfoot was sold to his original pro team, the Chattanooga Lookouts. Seventeen years after his initial engagement with Chattanooga, Barfoot went 15-12 for the Lookouts in 1931, combined with a 2.88 ERA, good for fourth in the league and only 0.03 behind the leader. However, he was best remembered that spring when he was pulled after two batters by manager Bert Niehoff in an April exhibition against the New York Yankees in favor of 17-year-old Jackie Mitchell, who proceeded to strike out Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig in the publicity stunt. Barfoot then returned to the hill in the Yankees 14-4 win.54

For the 1932 season, the 41-year-old Barfoot went 21-10, tying Alex McColl for the Lookouts club lead in wins, with seven shutouts and a league-leading ERA of 2.76.55 He shut out Knoxville 5-0 in the clinching game as Chattanooga captured its first pennant in 23 years.56 They met Beaumont, winners of the Texas League, in the Dixie Series. Barfoot lost the opener, 1-0, on a solo home run by 21-year-old Hank Greenberg.57 The Lookouts proceeded to win four straight to take the series. At the end of the 1932 season, the team (including Barfoot) went on a Mexican tour.58 After that concluded, Barfoot came back to California – by then he made his winter home in Hollywood. He continued to excel at his off-season pastime, golf, winning a driving contest in L.A. with a blast of 240 yards.59

Barfoot pitched to a 15-12 record for Chattanooga in 1933; he also worked at Samuel Stamping and Enameling Company in town.60 An amusing anecdote from that season came when Barfoot had two strikes on the opposing pitcher, decided to throw a knuckleball, and gave up a double. When club president Joe Engel demanded to know what Barfoot was thinking, the hurler replied, “Well, it was in the repertory, that’s all.”61

Barfoot developed neuritis late in the 1933 season after pitching in a cold night game. Thus, he faded down the stretch.

Starting his fourth year in his second stint with Chattanooga in 1934, Barfoot was 3-6 in 15 games over 81 innings.62 In early July, he transferred to the Atlanta Crackers. After Barfoot was victorious in his debut for his new club, the Atlanta Constitution proclaimed that, for the veteran, “life apparently begins at 40.”63 Though he was released in August, Barfoot landed with the Charlotte Hornets of the Class B Piedmont League.64

The 43-year-old Barfoot signed with the Wilkes-Barre Barons of the New York-Penn League, with a headline reading “One of Baseball’s Methuselahs to Pitch in NYP League.”65 He was almost immediately released, however – “somebody read that the former Cub and recent Southern League hurler was born in 1891 and the pink slip went out in the next mail.”66

He returned to Chattanooga, where former major-leaguer Whitey Glazner tried to get him a golf pro job. Instead, Barfoot joined a semipro squad out of Gainesville, Florida.67 In the late summer of 1935, he signed with Norfolk (Virginia) Tars back in the Piedmont League. In his final professional stop, Barfoot posted a 3-4 record, giving him a career minor-league record of 289-221.

Barfoot soon ran a grocery store in Chattanooga.68 In July 1938, he was asked to coach with Chattanooga by new manager and former Cardinals teammate Rogers Hornsby. Three days after debuting as a Lookouts coach, the 46-year-old finished a game on the mound against Memphis.69 He returned as a Chattanooga coach in 1939 for new manager Kiki Cuyler.

In March 1941, Barfoot became the golf pro at Signal Mountain Golf Club in Chattanooga, while wife Nell served as hostess.70 The couple resigned their posts in late 1942, in anticipation of Clyde’s opportunity to be a Red Cross club manager overseas.71 Instead, though, they moved permanently to southern California, where Clyde worked as a guard at Universal Studios.72 Studio guard Barfoot was photographed in 1956 in a syndicated shot with actresses Leigh Snowden and Dani Crayne.73 He also participated in annual Los Angeles Angels old-timers games.

Clyde’s wife Nell died in January 1951 in Los Angeles. Barfoot remarried that July to Elsi Heinen Rogers. In 1960, he won the Los Angeles City Senior Golf tournament for his age bracket (65-69).

Barfoot died on March 11, 1971, in Highland Park, California. He is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the Notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, StatsCrew.com, and MyHeritage.com

Notes

1 “Karpe’s Comment,” Buffalo Evening News, March 30, 1922: 26.

2 “Male Orphan Asylum School,” Richmond (Virginia) Dispatch, June 18, 1898: 2

3 F. Ellen Netting, Mary Katherine O’Connor, and David Fauri, “Capacity Building Legacies: Boards of the Richmond Male Orphan Asylum for Destitute Boys & The Protestant Episcopal Home for Infirm Ladies 1870-1900,” Western Michigan University, Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, September 2012 (Volume XXXIX, Number 3): 112.

4 “Sports Win from Farmers,” Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), July 6, 1906: 7.

5 “Fort Slocum to Play Yost Squad,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Farmer, November 14, 1913: 10.

6 “Mack Gets Twirler,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Democrat, August 28, 1913: 6.

7 “Harry Talks of Pitchers,” Chattanooga Daily Times, February 2, 1914: 7.

8 “Barfoot Seeks Early Release,” Chattanooga News, February 14, 1914: 16.

9 “Three More Players In,” Chattanooga Daily Times, March 6, 1914: 8.

10 “Another Lookout Goes to Paul Sentell’s Galveston Club,” Chattanooga Daily Times, May 1, 1914: 8.

11 Jack Nye, “Heavy Artillery is Turned on Lookouts,” (Nashville) Tennessean, April 22, 1914: 12.

12 “Barfoot Goes to Texas League,” Chattanooga Daily Times, April 30, 1914: 2.

13 “New Left Fielder Signed by Galveston Pirates,” Houston Post, March 4, 1915: 3.

14 “Pirate Pitcher Becomes Benedict in San Antonio,” Austin (Texas) American, April 21, 1916: 7.

15 “Barfoot Holds Nags Without a Hit or a Run,” Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), July 17, 1916: 8.

16 “Texas League Drops Two Clubs; Beaumont and Galveston Disband,” Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), May 19, 1917: 8.

17 “Barfoot Going Good,” El Paso (Texas) Herald, July 4, 1918: 9.

18 “Indians and Senators Divide Final Combats,” Indianapolis News, July 22, 1918: 12.

19 “Harry Heitman Class of International Twirlers,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), December 10, 1918: 23.

20 “Broncos and Browns Open Up Tomorrow,” San Antonio (Texas) Evening News, March 21, 1919: 12.

21 “Kelly Field and Nags to Meet Sunday,” San Antonio (Texas) Light, April 13, 1919: 21.

22 “San Antonio Hands Transfers to Two,” Collyer’s Eye (Chicago), May 15, 1920: 1.

23 “Only Two Hits off C. Barfoot,” Chattanooga Daily Times, May 12, 1920: 12.

24 Cliff Wheatley, “’Old Master’ Sheehan Lost Great Duel to Clyde Barfoot in Thirteen Innings, 1 to 0,” Atlanta Constitution, July 19, 1920: 7.

25 “Rickey Counting on Barfoot to Bolster Cards’ Pitching Staff,” Star and Times (St. Louis), January 15, 1922: 25.

26 “Rickey Counting on Barfoot to Bolster Cards’ Pitching Staff.”

27 “Mack Abandons an Idea in Picking Pate,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1921: 6.

28 “Cardinal Wreckers Triumph Over Yanks in New Orleans Game,” St. Louis Star and Times, March 19, 1922: 37.

29 Abe Yager, “’Screw Ball’ is the Latest Menace to Major Batters,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 28, 1922: 24. Oddly, on the exact same page of the exact same paper on the exact same day, an article ran comparing rookie Detroit pitcher Herman Pillette’s “fadeaway” pitch as on par, according to coach Dan Howley, to that of legend Christy Mathewson. See “Pillette’s Fade-Away Equals Mathewson’s,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, March 28, 1922: 24. However, conventional wisdom is that the screwball and fadeaway were one and the same pitch. Others, including Carl Mays, Elmer Myers, Dave Keefe, Alex Ferguson, Suds Sutherland, and Bullet Joe Bush, all were documented to have thrown a screwball before 1922.

30 “Barfoot Inherited His Moundsmanship,” Evening Journal (Wilmington, Delaware), August 7, 1922: 11.

31 Bill James and Rob Neyer, The Neyer/James Guide to Pitchers (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2004): 18.

32 “Hitting, Fielding, and Pitching Records,” Minneapolis Star, September 9, 1922: 8.

33 Charles Houston, “The Sport Critic,” Times Dispatch (Richmond, Virginia), August 26, 1934: 16. Barfoot was also referred to as “Boots” occasionally during his career.

34 James J. Murphy, “Toporcer is a Great ‘Sub’ for the Great Hornsby; Superbas are Shut Out, 4-0,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 9, 1923: 22.

35 “Screw Ball Artist to Pitch on Coast; Buffs Get Sellars (sic),” Houston Post, December 20, 1924: 14.

36 “Gassers End Clyde Barfoot’s Row of Scoreless Innings,” Houston Post, June 3, 1924: 10.

37 “Clyde Barfoot is Slugging Star of Buffalo Offensive,” Houston Post, August 27, 1924: 10.

38 Sam Greene, “Ty Looks Cheerily to His Barfoot Boy,” The Sporting News, December 31, 1925: 4.

39 “Barfoot Beats Seraphs,” Los Angeles Times, October 16, 1925: 41.

40 “Barfoot Sold to Detroit for $35,000, is Report,” Daily News (Los Angeles), September 5, 1925: 19; Sam Greene, “Tigers’ Big Splash Comes Trifle Late,” The Sporting News, September 10, 1925: 1.

41 “Geo. Carr Hits Two Home Runs as Royals Drive Payne to the Bench,” California Eagle (Los Angeles), December 11, 1925: 9.

42 “New Claw in the Tiger Paw,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1926: 6.

43 Sam Greene, “Ty Makes Six Additions, Three of Them Pitchers,” The Sporting News, April 15, 1926: 6.

44 A first-person account came from Bill Moore, who was also in that camp. See Richard Bak, Cobb Would Have Caught It, Detroit, Michigan: Great Lakes Books (1991): 170.

45 “Deaths,” Times Dispatch, May 8, 1926: 10.

46 “Chicago Hammers Detroit Pitchers” Bristol (Tennessee) Herald Courier, May 25, 1926: 7.

47 “Clyde Barfoot is Returned to Mission Team,” Daily News, May 26, 1926: 19

48 Sam Greene, “Tigers Get Chance to Prove a Theory,” The Sporting News, June 3, 1926: 1.

49 Dennis Snelling, The Pacific Coast League: A Statistical History, 1903-1957 (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 1995): 249.

50 F.T.B., “Winter League Draws Its Players from O.B.,” The Sporting News, October 28, 1926: 3.

51 Stub Nelson, “The Second Guess,” Los Angeles Evening Post-Record, April 7, 1930: 8.

52 Matt Gallagher, “Coast League 1930 Baseball Season Opens,” Los Angeles Evening Express, April 8, 1930: 1.

53 Clyde Barfoot, “Angels Great Fielding Club,” Evening Express, April 9, 1930: 23.

54 L. Robert Davids, “Women Players in Organized Baseball,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, 1983.

55 “Baseball Notes,” Brooklyn Citizen, September 27, 1932: 7.

56 Wirt Gammon, “Chattanooga Wins 1932 Pennant,” Chattanooga Daily Times, September 12, 1932: 1. Memphis (101-53) actually finished one-half game ahead of Chattanooga (98-51) in the standings, but Chattanooga held a better winning percentage (.658 vs. .656) and was thus awarded the pennant.

57 Wirt Gammon, “Beaumont Beats Chattanooga, 1-0, in Opening Battle of Dixie Series, Home Run Deciding Pitchers’ Duel,” Chattanooga Daily Times, September 21, 1932: 1.

58 “’Noogans Delay Slice of Share to Later Meet,” Chattanooga Daily Times, September 27, 1932: 8.

59 “Golf Season Opens for Clyde Barfoot with Quick Birdies,” Chattanooga Daily Times, November 8, 1932: 8.

60 Wirt Gammon, “Sports Parade,” Chattanooga Daily Times, October 10, 1933: 8.

61 Edgar G. Brands, “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1933: 4.

62 “Weintraub Hogging League Bat Honors,” Birmingham News, July 1, 1934: 17.

63 Jimmy Jones, “Barfoot Bests Milnar, 3 and 2, in Night Game,” Atlanta Constitution, July 6, 1934: 16.

64 “Barfoot Takes George’s Place as NYP’s Dean,” Press and Sun-Bulletin (Binghamton, New York), April 15, 1935: 18.

65 “Barons Will Have Veteran Performer,” Standard-Speaker (Hazelton, Pennsylvania), April 5, 1935: 19; Bill Reedy, “One of Baseball’s Methuselahs to Pitch in NYP League,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Eagle, April 5, 1935: 28.

66 Joe Walsh, “Sport Chatter,” Wilkes-Barre Record, April 8, 1935: 18.

67 “Clyde Barfoot Goes to New Florida Job,” Chattanooga Daily Times, April 25, 1935: 10; “Barfoot Gets Offer to Play with Neis’ Gainesville Outfit,” Chattanooga News, April 24, 1935: 13.

68 “Baseball Fans Bilked by Wrestling Barfoot,” Nashville Banner, February 4, 1936: 8.

69 “Lookouts Put on Bat Show to Split with Memphis on ‘Old Folks’ Day,” Chattanooga Daily Times, July 18, 1938: 8.

70 Austin White, “1932 Chattanooga Lookout Hero Realizes a Cherished Ambition,” Chattanooga Daily Times, March 30, 1941: 20.

71 “Barfoot’s Off,” Chattanooga Daily Times, November 13, 1942: 4.

72 Rube Samuelsen, “Sport Volleys,” Pasadena Post, May 11, 1943: 7.

73 “It’s ‘Batter-Up’ Time Again,” Lubbock (Texas) Evening Journal, April 25, 1956: 34.

Full Name

Clyde Raymond Barfoot

Born

July 8, 1891 at Richmond, VA (USA)

Died

March 11, 1971 at Highland Park, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.