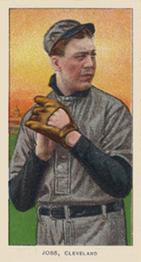

Addie Joss

For nine seasons Addie Joss was one of the best pitchers in the history of the American League, posting four 20-win seasons, capturing two ERA titles, and tossing two no-hitters (one of them a perfect game) and seven one-hitters. Of Joss’s 160 career victories 45 were shutouts, and his career 1.89 ERA ranks second all-time only to his long-time rival Ed Walsh among players with 1,000 innings pitched. An exceptional control pitcher with a deceptive pitching motion, the right-handed Joss employed a corkscrew delivery, turning his back entirely to the batter before coming at him with a sidearm motion that confused most hitters. “Joss not only had great speed and a fast-breaking curve,” Baseball Magazine observed in 1911, “but [also] a very effective pitching motion, bringing the ball behind him with a complete body swing and having it on the batter almost before the latter got sight of it.” After nearly pitching the Naps to their first pennant in 1908, illness and injury limited Addie’s endurance during his final two major league seasons, before his life was tragically cut short at the age of 31 by a bacterial infection.

For nine seasons Addie Joss was one of the best pitchers in the history of the American League, posting four 20-win seasons, capturing two ERA titles, and tossing two no-hitters (one of them a perfect game) and seven one-hitters. Of Joss’s 160 career victories 45 were shutouts, and his career 1.89 ERA ranks second all-time only to his long-time rival Ed Walsh among players with 1,000 innings pitched. An exceptional control pitcher with a deceptive pitching motion, the right-handed Joss employed a corkscrew delivery, turning his back entirely to the batter before coming at him with a sidearm motion that confused most hitters. “Joss not only had great speed and a fast-breaking curve,” Baseball Magazine observed in 1911, “but [also] a very effective pitching motion, bringing the ball behind him with a complete body swing and having it on the batter almost before the latter got sight of it.” After nearly pitching the Naps to their first pennant in 1908, illness and injury limited Addie’s endurance during his final two major league seasons, before his life was tragically cut short at the age of 31 by a bacterial infection.

Adrian Joss was born on April 12, 1880, in Woodland, Wisconsin, the only child of Jacob and Theresa Joss. Jacob was a native of Switzerland who had emigrated to Wisconsin to learn the cheese-making trade, eventually owning his own factory in Woodland. He died in 1890, apparently of liver disease caused by alcoholism, when Addie was only 10 years old. Theresa was a well-educated woman whose father had ties to politics in Caledonia, Wisconsin. After her husband’s death Theresa opened a millinery shop and sewing school in Juneau, Wisconsin, which provided her family with some financial support.

As he grew Addie developed into a tall, skinny boy with noticeably long arms. These attributes would one day earn him the nicknames the Human Slat and the Human Hairpin. It was an ideal physique for a pitcher, but Joss’s first ventures in baseball came as a second baseman on the Juneau high school team. After graduating in 1896, he entered the teaching profession in the town of Horicon, Wisconsin. In the summer he joined the town baseball team as a pitcher, developing the unusual pitching motion that would eventually bring him fame in the major leagues. Despite turning his body toward second base and kicking his leg high into the air, Joss did not fall off the mound in his follow-through, but rather completed his motion upright, ready to field any ball that came his way.

In 1899 Joss joined the Oshkosh, Wisconsin, baseball team after he was offered $10 a week to play for them. There was little interest in the team, however, and repeated financial crises caused the owners to freeze the players’ salaries. After the initial Oshkosh team was disbanded, Addie accompanied a second team to Manitowoc, Wisconsin, as the second baseman. Soon after, he joined the premier Manitowoc team, finally as a pitcher, and won four games against only one defeat. At the end of the season, he was offered his first professional contract, by the Toledo Mud Hens of the Inter-State League.

On April 28, 1900, he started Toledo’s opening day game, holding on to win his first professional start 16-8. (Among those in attendance was a young woman named Lillian Shinavar; two years later, on October 11, 1902, Addie and Lillian were married in Monroe, Michigan.) Joss went 19-16 in his first season, and the following year won 25 games and struck out 216 batters. It was a performance good enough to merit an invitation to spring training with the Cleveland Bronchos of the American League. At 6’3″ and 185 pounds, the Human Slat impressed Cleveland management with his performance, and made the team out of spring training.

Joss burst onto the major league scene with one of the greatest debuts of any pitcher in history. On April 26, 1902, against the St. Louis Browns, he set down batter after batter, taking a no-hitter into the sixth inning. The Browns’ Jesse Burkett led off the sixth with a short bloop fly to right field. Outfielder Zaza Harvey tried to make a sliding catch, but the play was ruled a base hit by home plate umpire Bob Caruthers, sparking a heated protest from Cleveland. At the plate, Joss, who would finish his major league career with a .144 batting average, added what appeared to be a home run, but it was ruled a double by Caruthers–who nevertheless allowed a runner to score from first base. In the end, Joss allowed only the one scratch hit and beat the Browns easily, 3-0. Addie won 17 games during his rookie season, led the league with five shutouts, and finished with a 2.77 ERA. He was subsequently invited to play for the All-Americans, a team made up of American League all-stars who played a similar team from the National League during a winter tour.

Joss continued to show improvement during the 1903 season, finishing the year with 18 victories and a 2.19 ERA, but he really came into his own in 1904, when he led the league with a 1.59 ERA, (although illness limited him to just 24 starts and 14 wins). In 1905 a healthy Joss achieved his first 20-win season, posting a 20-12 ledger with a 2.01 ERA, a performance which earned him a $500 bonus. Joss’s stellar work in the 1906 season, in which he went 21-9 with a 1.72 ERA, third best in the league, earned him another bonus. After the 1906 campaign Joss took an off-season job with the Toledo News Bee as the writer of a Sunday sports column. In his column, which Joss penned himself, Addie spoke of serious baseball issues, related humorous stories from his own experiences in the game, and also covered the Mud Hens and other local baseball teams. He would become known as an extremely talented and popular sportswriter, especially for his coverage of the World Series. Joss’s familiar voice in the column gave him greater fan support during his holdout for a salary increase before the start of the 1907 season. He finally settled for a $4,000 contract.

Joss won his first ten starts in a row to begin the 1907 season. That year he would tie for the American League lead with 27 victories. One of these victories was on September 5, when he threw a one-hitter against the Detroit Tigers. Three weeks later, on September 25, Joss fired another one-hitter, this time against the New York Highlanders. The following day, teammate Heinie Berger followed with his own one-hitter, marking the second time since 1900 that teammates threw back-to-back one-hitters.

On his way to a second ERA title, Joss pitched brilliantly for the Naps in 1908, keeping them in a tight three-way pennant race. He saved his best performance for October 2, when he squared off against Big Ed Walsh of the Chicago White Sox at Cleveland’s League Park. Going into the contest, Chicago trailed the Naps by one game, and Cleveland stood a half game behind the front-running Detroit Tigers. Walsh matched Joss pitch for pitch, striking out 15 Naps while holding the team to only four hits. In the third inning, a passed ball by Chicago catcher Osee Schrecongost allowed Cleveland outfielder Joe Birmingham to score. Joss kept the White Sox in check and had a 1-0 lead and a perfect game as the contest rolled into the ninth frame. Of the tension in the ballpark, one writer said that “a mouse working his way along the grandstand floor would have sounded like a shovel scraping over concrete.”

After Joss retired the first two batters, pinch hitter John Anderson smashed a would-be double down the line that barely went foul. Anderson then grounded harmlessly to third baseman Bill Bradley, who added to the tension by bobbling the ball and then throwing it low, but first baseman George Stovall dug out the throw to preserve the 1-0 perfect gem. Joss needed only 74 pitches to out-duel Walsh and retire all 27 White Sox batters. It was only the second perfect game in American League history.

Although the win put the Naps two games ahead of Chicago, the Detroit Tigers would prevail over both the Naps and the Sox, capturing the pennant with a win over Chicago on October 6. The Naps finished the season just half a game behind the Tigers, the closest to a World Series Joss came during his career. Joss finished the season with 24 wins, his last 20-win season, and the ninth-lowest single-season ERA in baseball history, 1.16. He also walked only 30 batters in 325 innings pitched.

Joss spent the 1908-09 off-season hitting the engineering books, designing an electric scoreboard that would allow fans to keep track of balls and strikes. Joss successfully marketed the device to Cleveland management, who installed the Joss Indicator on a new, larger scoreboard at League Park, which also posted the lineups of both teams on either side of the balls and strikes. Unfortunately, Addie struggled with fatigue throughout the season and was relegated to the bench for much of September as the Naps finished a disappointing sixth.

Joss seemed to have regained his strength at the beginning of the 1910 season. On April 20 he tossed a no-hitter, once again against the White Sox. The only drama from the White Sox came in the second inning when shortstop Freddy Parent lightly topped a ball to Cleveland third baseman Bill Bradley. Bradley raced toward the ball, but juggled it and failed to get Parent before he crossed first base. The initial ruling on the play was a base hit, but the official scorer later changed it to an error on Bradley. Luckily for Joss the ruling stood, as he allowed only two walks on his way to throwing his second career no-hitter. He also aided his own cause with a fine defensive effort, fielding ten balls from the mound flawlessly and earning ten assists. It was the last great performance of Addie Joss’s career. A torn ligament in his right elbow limited Addie to only 13 appearances in 1910. His final career regular-season appearance came on July 25, pitching five innings against the Athletics before leaving with complications from the elbow injury.

Joss continued to report arm trouble in early 1911, although he expected to be able to pitch by May after some rest. On April 3, however, before an exhibition game in Chattanooga, Tennessee, he fainted on the field while talking to his friend, Chattanooga shortstop Rudy Hulswitt. His condition continued to worsen and Joss returned to Toledo, where his personal physician, Dr. George Chapman, diagnosed an attack of pleurisy. In the early morning hours of April 14, two days after his 31st birthday (which fell on opening day), Joss died suddenly of tubercular meningitis. Later that day, devastated teammates spoke highly of Addie: “No better man ever lived than Addie,” said George Stovall, and Napoleon Lajoie added, “In Joss’s death, baseball loses one of the best pitchers and men that has ever been identified with the game.”

Joss’s funeral was held in Toledo on April 17, a day when Cleveland had a scheduled game against Detroit. Despite orders from American League President Ban Johnson for the Naps to play the game, all of Joss’s Cleveland teammates insisted on attending the funeral. George Stovall, the Naps team captain, declared his team on strike, proclaiming, “I may be captain, but I’m still a ballplayer.” Finally Johnson relented, and the game was postponed. Former ballplayer turned evangelist Billy Sunday delivered Addie’s eulogy at the funeral, which at the time was the second-largest in Toledo’s history. “Joss tried hard to strike out death, and it seemed for a time as though he would win,” Sunday proclaimed. “The bases were full. The score was a tie, with two outs. Thousands, yes, millions in a nation’s grandstands and bleachers sat breathless watching the conflict. The great twirler stood erect in the box. Death walked to the plate.”

Joss was buried at Woodlawn Cemetery in Toledo, Ohio. Two months later, on July 24, a group of all-stars from throughout the American League played the Cleveland Naps in an exhibition game to benefit Joss’s widow, Lillian, and their two children. Walter Johnson and Joe Wood pitched for the all-stars against Cleveland’s Cy Young. Some of the other stars who participated included Ty Cobb, Sam Crawford, Eddie Collins, and Tris Speaker. Over 15,000 tickets were sold for the game which saw the all-star team win 5-3; more importantly, the game raised $12,914 for Joss’s family.

In 1978 the Veterans Committee of the Baseball Hall of Fame sidestepped the minimum ten seasons played rule and elected Joss to the Hall of Fame, 67 years after his untimely death.

A version of this biography originally appeared in “Deadball Stars of the American League” (Potomac Books, 2006), edited by David Jones.

Sources

Scott Longert. Addie Joss: King of the Pitchers. SABR, 1998.

Baseball: 100 Classic Moments in the History of the Game. DK Publishing, 2000.

John Thorn, et. al. Total Baseball, Fifth Edition. Viking, 1997.

Cooperstown: Where the Legends Live Forever. Gramercy, 2001.

www.baseball-almanac.com

www.baseballlibrary.com

Gabriel Schechter, Baseball Hall of Fame

Full Name

Adrian Joss

Born

April 12, 1880 at Woodland, WI (USA)

Died

April 14, 1911 at Toledo, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.