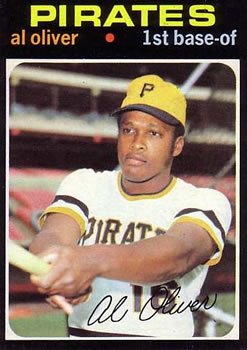

Al Oliver

“I’m going to have a good year because I’m Al Oliver. I always have a good year. The question is how good.”1

“I’m going to have a good year because I’m Al Oliver. I always have a good year. The question is how good.”1

That confident self-assessment came in 1978, a little over halfway through this slashing line-drive hitter’s long and successful career. In 18 seasons, the lefty-swinging first baseman-outfielder amassed 2,743 hits and posted a .303 batting average. His extra-base pop — including 219 homers — brought his slugging percentage to .451.

As a rookie in 1969, Oliver said, “I won’t strike out a lot if I play every day. I generally make contact.”2 Indeed, over the course of his big-league career, he struck out in only 8% of his plate appearances and walked in 5%. He hit the ball where it was pitched and used the whole field.

Oliver’s confidence — and differing perceptions thereof — was a central topic of many stories about him in his playing days. But as he has often been quoted, “There’s no such thing as bragging. You’re either lying or telling the truth.”3

Albert Oliver Jr. (he has no middle name) was born on October 14, 1946, in Portsmouth, a small city in southern Ohio. His father, Albert Oliver Sr., was apparently a professional basketball player in the 1940s, but information on the league and/or team has not yet surfaced. He then went to work in a brickyard. Al’s mother was Sallie Jane (née Chambers). “Janie” was known for her good home cooking. There were also two younger children in the family named Paula and James.

Al Jr. told author George Castle, “I was brought up properly. I had great parents who raised me. . . They didn’t raise a son who was cocky and arrogant. They raised a son who was self-assured.”4 In the two books that he has written about himself, Oliver emphasized the deep influence that his parents had on him. He added that the strength of the Portsmouth community also played a big part in his upbringing. Oliver’s church has always been central to his sense of community. His Christian faith is the foundation on which his life is built. As a youth he began to cultivate a deep knowledge of the Bible.

From the time he was very small, Oliver carried a ball with him and bounced it. He wasn’t even a year old when his mother predicted that he would become a ballplayer. Like his father, Oliver was talented at basketball, in which being ambidextrous was an asset. In his own view, he could have made the NBA, but he acknowledged that at his height (six feet even) he would have been just a reserve. He also played football and a variety of other games, except on Sundays, when church attendance and a day of rest were a family mandate. As an adult, racquetball became his favorite other recreational activity.

Portsmouth is not a big place. Its population was only 30-40,000 when Oliver was growing up, and has since declined as the economic base eroded. Yet it produced another high-quality major-league hitter in Larry Hisle, born several months after Oliver. They knew each other from around age five, playing baseball and basketball with and against each other.

Oliver’s Little League team won a championship when he was nine. Their reward was to go to Cincinnati (about 100 miles northwest of Portsmouth) and see the Brooklyn Dodgers play the Reds at Crosley Field. Jackie Robinson, about whom Oliver had learned in school, was there and so it felt like watching history. He also said to himself that he could hit the Reds pitcher and remembered thinking that baseball was something in which he could excel.5

According to a 1971 feature, when Oliver was in grade school, his favorite team was the Pittsburgh Pirates, the club that signed him first and with whom he spent the first half of his major-league career. The man he admired most in the game was Bill White.6 In his first memoir, however, Oliver said that he grew up a Reds fan and that Vada Pinson was his favorite player.

In January 1958, Janie Oliver passed away at the untimely age of 33 (young Al was told she’d had a heart attack). Larry Hisle lost his mother a couple of months later, and the deaths helped forge a bond between the youngsters that continued throughout their lives.

Oliver entered Notre Dame High School, a private Catholic institution in Portsmouth, as a freshman. His father was making the point that education came before sports. He switched to Portsmouth High School as a sophomore, however, and thus lost a year of playing interscholastic varsity sports (though he practiced and traveled with his teams). As a teenager, he also played American Legion baseball on a team that included Hisle and another future major leaguer, Gene Tenace (who lived in nearby Lucasville). He started attracting attention from big-league scouts after breaking a car windshield with a hot line drive. He mused that if it hadn’t been for that liner, playing and coaching basketball could well have wound up being his career path.

Oliver had a basketball scholarship offer to attend Kent State University in northern Ohio, where he planned to play baseball as well. That summer, however, the 17-year-old attended a Pirates tryout camp in Salem, Virginia conducted by scouts Syd Thrift, Joe Consoli, and others. He signed for $5,000 and was assigned to Pittsburgh’s farm club in Salem.7

Oliver’s recollection was that the Pirates gave him $4,000 plus an offer to pay for his education. He later found out that the Philadelphia Phillies would have offered him substantially more money, which taught him a lesson.

Unfortunately, Oliver got hurt shortly after he signed, and there are at least two versions of the incident. As Thrift later told the story, Oliver called and said he couldn’t walk because his knee had locked up after jumping on the street with a friend.8 By Oliver’s own account, it came while sliding into second during a training session. At any rate, he was taken to a Pittsburgh hospital and underwent surgery on the knee. He played no baseball for the rest of the year (briefly attending Kent State that fall), and the Pirates actually exposed him to the minor-league draft. Not surprisingly, no team was willing to shell out the $8,000 that it would have taken.9

Oliver spent four years in the minors. Rising through the Pittsburgh system with him was pitcher Dock Ellis, the first player he met in camp in 1965 and the best friend he ever made in baseball. Oliver missed the early part of the 1967 season while serving with the National Guard in Ohio. That was true of many ballplayers during the Vietnam War. Previously, Oliver’s father had served, either in World War II or Korea.10

Oliver did not face racism until his teens. Although he first experienced this unhappy reality in Portsmouth, it wasn’t overt, as it was while playing as a minor-leaguer in the southern U.S. from 1965 through 1967 (Western Carolinas League, Carolina League, Southern League). Racial epithets and being denied restaurant service were part of what he had to endure. Looking back in 2016, Oliver said, “I had a lot of fun. But I really didn’t know much about the South at the time. We didn’t go through the things that Jackie Robinson went through or some of the black players right before me, like (Willie) Stargell. But we still heard the catcalls. All we could do was keep hitting. That would silence some of them. In some ballparks it didn’t. It was just part of society at the time.”11

Oliver started slowly with Triple-A Columbus in 1968, and manager Johnny Pesky later admitted that in mid-May he had been on the verge of demoting the prospect to York in the Double-A Eastern League. But Oliver heated up, finishing the year at .315 with 14 homers and 74 RBIs, so Pesky was glad that he’d changed his mind. A rival manager, Frank Verdi of Syracuse, called Oliver the best hitter in the International League.12

Accordingly, the Pirates called Oliver up in September; he never played another game in the minors. However, he didn’t make his big-league debut until the 23rd. By one account, he had to recover from an attack of the flu, which sidelined him for all but the opening game of the IL playoffs.13 The bigger issue that year, though, was the health of Al Oliver Sr., which was in serious decline from the occupational hazard of inhaling brick dust. Al Jr. went back to Portsmouth frequently during the season and got the sad news that his father had passed away the same day he heard that he was going to The Show.

After returning from bereavement leave, Oliver first appeared as a Pirate in right field, a position he had never played before. He spelled Pittsburgh’s star right fielder, Roberto Clemente. Of Clemente, he later said, “Outside of my parents, Roberto had the biggest impact on me. He might have been the only one in the organization who understood me. He was raised the same way. He proved you could have an ego but not be egotistical, confident but not cocky, humble when [he] needed to be, but, most of all, maintaining your dignity and self-respect in spite of all the negative obstacles that were in his way.”14

The first-base job in Pittsburgh opened up after the Pirates exposed Donn Clendenon to the expansion draft and he was selected by the Montreal Expos. However, another first baseman was in the mix too: slugger Bob Robertson. Robertson, who had missed 1968 with a kidney ailment, caught manager Larry Shepard’s eye in the Florida Instructional League. As a result, the Pirates wanted to see how Oliver could fit in as an outfielder.15

Though he did play some outfield, Oliver was the Bucs’ primary first baseman in 1969, especially after Robertson was sent down to Columbus in May. That month, Johnny Pesky (who had become a Red Sox broadcaster) noted that even when Oliver hadn’t been hitting in 1968, he wasn’t being fooled on pitches. Although he had a tendency to overswing at times, the talent was there, as well as a willingness to listen and take instruction. Pesky added, “Forget his average, forget his ability to play first base so well, you can forget almost everything except that Oliver is the type of ballplayer who helps you win games.” 16 Oliver’s work around the bag, especially his ability to dig out low throws, won him a lasting nickname: “Scoop.”

Pittsburgh also used Willie Stargell, who was already suffering from knee problems, at first from time to time, as well as Carl Taylor. After a slow start and a leg injury, Oliver started swinging the bat well in mid-July.17 He wound up with a .285/.333/.445 batting line and tied for second with Montreal’s Coco Laboy in the NL Rookie of the Year voting in 1969. The winner was Ted Sizemore of the Los Angeles Dodgers, a much lighter hitter (.271/.328/.342) whom the baseball writers liked for his steady play as a middle infielder.18 Oliver thought he’d clearly had a better year than Sizemore and that it established a pattern: lack of respect from the media. Yet he came in fifth (after Laboy, teammate Richie Hebner, Sizemore, and old pal Larry Hisle) in the players’ voting for The Sporting News NL Rookie Player of the Year.19

Oliver also survived a scary episode in the season finale, a night game at old Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. He had three or four pieces of a cake that had been delivered to the clubhouse, unaware that it contained tree nuts, to which he’d been allergic since he was a boy. He felt okay as the game started but had to leave as the reaction to the nuts became severe. A doctor came out of the stands and treated him in the clubhouse, where he had passed out. Finally, he received an injection that revived him.20

On April 8, 1970, Oliver got married to Donna Allen, who’d been working as a babysitter for a Stargell family friend. Willie, who had introduced the couple, served as best man at their wedding. Al and Donna had a daughter named Felisa and a son named Aaron. Although Donna was African-American, her complexion was quite fair. This led at times to misperceptions of an interracial marriage and more unpleasant encounters with racism.

Bob Robertson became the main first baseman for the Pirates in 1970 and had his best year in the majors. Oliver still started 64 games at first, along with 52 in right (Clemente appeared in just 108 games that year) and 27 in left. As a result, he played in 151 games and got to the plate 609 times, both second on the team behind Matty Alou. “He’s in there every day for a number of reasons,” said manager Danny Murtaugh. The skipper was referring mainly to Oliver’s hard hitting, even when he made outs.21 Yet the platooning and shuffling didn’t sit well with Oliver, who could display a furious temper in his early years as a Pirate.

The Pirates, an up and coming club, became known as “The Great Lumber Company” for their potent lineup. Oliver was one of those dangerous hitters, and Pittsburgh wanted to find a regular position for both him and Robertson. Therefore, after the 1970 season, the front office sent Oliver to play center field in Puerto Rican winter ball with the San Juan Senadores. His manager there was none other than Clemente.22

He acquitted himself so well that not only Clemente but also coach Bill Virdon — a superb center fielder in his playing days — endorsed him for the center-field job with Pittsburgh.23 Thus, the Pirates traded Alou, their regular in center for the past five seasons, in January 1971. Although some questioned whether Oliver had a strong enough arm for the outfield, he got the job done and had respectable range, too. His willingness to move away from his best position for the good of the team was noteworthy.

Pittsburgh won five National League East division titles in six years from 1970 through 1975. The team won the NL Championship Series just once in that span, in 1971. In the clinching Game Four vs. the San Francisco Giants, Oliver’s three-run homer in the sixth inning off Jerry Johnson was the crowning blow in the Pirates’ 9-5 victory. They then went on to defeat the Baltimore Orioles in the World Series.

Another notable moment during the 1971 season came on September 1. Danny Murtaugh happened to write out an all-black lineup, the first ever in the majors. In addition to Oliver, batting seventh and playing first base, the lineup consisted of Rennie Stennett (2B), Gene Clines (CF), Clemente (RF), Stargell (LF), Manny Sanguillen (C), Dave Cash (3B), Jackie Hernández (SS), and Dock Ellis (P). Murtaugh said that he was simply playing those he felt gave the Pirates the best chance to win — which the Pirates did that night, 10-7.

Oliver started just 21 games at first base in 1971, and it was especially unusual that he was starting that evening against a left-hander, because Murtaugh had benched him against most southpaws that season. When asked about the possible reasons 30 years later, Oliver replied with a laugh, “That’s a good question, because to this day when people ask me who was the toughest pitcher I ever faced, it was Woodie Fryman,” the Phillies’ starter. Author Bruce Markusen’s research found one article indicating that Bob Robertson sat out the game with an unspecified minor injury, but according to Oliver, Murtaugh may have been looking to light a fire under a slumping Robertson.24

A point of greater interest is that the Pirates club, as well as Murtaugh, was truly color-blind. Oliver didn’t even realize that men of color made up the whole lineup until the game was well under way. “It really wasn’t a major thing, until around the third or fourth inning,” he recalled in 2016. “Dave Cash was sitting next to me, and one of us said, ‘You know, we got all brothers out there, man,’ and we kind of chuckled because it was no big deal to us. We really had no idea that history was being made.” He also echoed what he’d said in 2001, that this seminal moment in baseball history deserved fuller attention.25

Oliver remained the Bucs’ primary center fielder through 1976, although he still played a fair amount at first. He was an NL All-Star in 1972, 1975, and 1976. His .321 batting average in 1974 was second in the NL behind Ralph Garr.

In 1977, Oliver shifted to left field as the swift Panamanian Omar Moreno took over in center. At age 30, he hoped to play for another decade, and he already had set a goal of reaching 3,000 career hits.26 Yet he had a distinct feeling that the 1977 season would be his last in Pittsburgh. He was approaching “10-and-5” status — i.e., 10 years of major-league service time, the past five straight with the same team. That would have enabled him to veto any trade, and he surmised that management wanted to avoid such a situation.

Sure enough, that December Oliver went from Pittsburgh to the Texas Rangers as part of a complicated four-team trade that also involved the Atlanta Braves and New York Mets. A subsequent report in February 1978 noted that despite Oliver’s production as a Pirate, his years there were often stormy. It quoted Oliver as saying the deal was the best thing that could have happened to him. “When you’ve had the kind of years I had for the Pirates, and your name still continually came up in trade talks every winter, you begin to wonder sooner or later about just how sincere management is.”27 Yet in his heart, Oliver would have been happy to remain in Pittsburgh for his entire career.

When Oliver joined the Rangers, he asked for the uniform number 0, which he wore for the rest of his career. Some people thought it was an O, symbolizing his last name, and he agreed that it made sense. But his mindset was that “zero is a starting point, and I wanted to start all over again.”28

Oliver lived up to the self-assessment he issued after the trade about always having a good year. During his four seasons in Texas, he hit over .300 each season and .319 overall. In his first year as a Ranger, he was runner-up for the AL batting crown behind Rod Carew. He was an AL All-Star in 1980, when he won his first Silver Slugger award while playing left field. Early that season, a feature in Sports Illustrated called him “baseball’s best-kept secret,” a phrase that later became part of his first book’s title.29

Bone spurs in Oliver’s shoulder forced a move to designated hitter in 1981, but he was again an AL All-Star and picked up another Silver Slugger award. He found living in Arlington very agreeable and also thought the school system was strong, which was important for his children.

Oliver had four years remaining on his contract but sought an extension and was turned down, even though he was asking for less than market value because he liked it in Texas. So, near the end of spring training 1982, after a deal with the Yankees fell through, the Rangers traded him to the Montreal Expos for Larry Parrish and Dave Hostetler.30

The Expos, who had a starting outfield of Tim Raines, Andre Dawson, and Warren Cromartie, put Oliver at first base. Going back in the field pleased him, as did the return to the NL, which he viewed as the more aggressive league. Montreal had been seeking a lefty bat for the cleanup slot to fit in between the righty power of Dawson and Gary Carter.31 The team also had budding star Tim Wallach ready to take over third base from Parrish. After nearly winning the NL pennant in 1981, Montreal hoped to break through to the next level of success.

Bone spurs still hampered Oliver’s throwing severely, and he did the best he could by following the exercise regimen he’d been prescribed in Texas. (Dr. Frank Jobe had recommended against surgery based on Oliver’s age, then 35.) But his shoulder was not a problem at bat — he had his best year ever in 1982, setting career highs in hits (204), average (.331), and homers (22). His average led the NL, as did his 43 doubles and 109 RBIs. “Al had a very businesslike approach to the game,” said Raines. “Nobody squared up a pitch and hit a ball harder than Al.”32

Looking back in 2014, Oliver thought a lot of people missed the boat with their perception of him.33 The spin in media reports was often negative, and race factored into this, in his opinion and friends’ view, too. During his playing days, he remained skeptical about how writers portrayed him, despite his accomplishments and the sacrifices he had made on behalf of his teams. “The news media can make you a god or a devil,” he said in 1985.34

Yet one of the most perceptive portraits of Oliver came in the Montreal Gazette in June 1982. Columnist Michael Farber acknowledged the opposing views: “arrogant or honest, a clubhouse lawyer or a clubhouse leader, selfish or a team player.” Digging deeper, the full-page feature recognized him as “a cheerful, accommodating boy scout of a man” (he didn’t smoke or drink). Toward the end, it captured Oliver’s style succinctly: “Ever gentle, ever serious, he told them what he thinks.”35

Montreal hosted the All-Star Game in 1982, and the crowd at Olympic Stadium gave Oliver tremendous applause when he was announced. His friend Dusty Baker turned to him and said, “Scoop, that was a once in a lifetime ovation.” The recognition continued in the offseason. Though Oliver had received some consideration for the Most Valuable Player award in eight previous seasons, he tied for third in the 1982 NL MVP voting.

Oliver followed with another good season, albeit a sizable step down from his production in ’82: .300 with 8 homers and 84 RBIs. Again he made the All-Star team. Even so, he had a feeling early in the season that he wouldn’t be back with Montreal in ’84 if the Expos didn’t become champions.36 Lack of leadership was also perceived as an issue, even though Raines and Dawson (to name just two teammates) looked up to Oliver. Expos broadcaster Dave Van Horne cited the absence of Parrish, calling him the one who could rally the troops.37 Yet according to ace pitcher Steve Rogers, it was unfair to put Oliver in this spot coming to a new team full of homegrown players.

Again Oliver’s sense proved accurate. After finishing third in the NL East again in 1983, Montreal traded him to the San Francisco Giants in February 1984. The Expos received pitcher Fred Breining, outfielder Max Venable, and a player to be named later (another pitcher, Andy McGaffigan). The previous month, Montreal had signed Pete Rose as a free agent, and there was talk that Rose would move back to left field, where he had played for several seasons in the late ’60s and early ’70s. Instead, Rose stayed at first base, but he wore the Expos uniform for less than one season.

Oliver shared first base in San Francisco with another lefty, Scot Thompson. Although they both hit for good average, they hit just one home run (Thompson’s) between them. Along with the dropoff in Oliver’s power, it later emerged that manager Frank Robinson had doubts about the condition of the veteran’s shoulder. On August 20, San Francisco sent Oliver and a player to be named later (pitcher Renie Martin) to Philadelphia for pitchers Kelly Downs and George Riley. Phillies first baseman Len Matuszek was hitting just .240, and the team wanted another lefty bat after Tim Corcoran and Joe Lefebvre had gotten hurt and Jeff Stone was demoted.38

Though Oliver hit well for the Phillies (.312), he was traded again in February 1985. He went to Los Angeles for pitcher Pat Zachry, who was near the end of the line. The series of trades, in Oliver’s view, conveyed a lack of respect.

The Dodgers acquired Oliver with an eye toward using him in left field, which he’d played a little for Philadelphia, his first outfield action since 1980. He was also insurance behind first baseman Greg Brock, who’d hit just .224 as a rookie. Oliver reassured Brock that as long as they both did their jobs, all would be well.39

Oliver’s return to regular outfield duty did not go well, though, so he served mainly as a pinch-hitter for L.A. after April. He got into just 35 games and made just 85 plate appearances. He asked manager Tommy Lasorda about a trade to someplace where he could be used, and the Dodgers obliged, sending him to the Toronto Blue Jays in early July for Len Matuszek, whom the Phillies had dealt away not long after Oliver. The return to the AL, with the DH rule, gave Oliver more at-bats.

The Blue Jays won the AL East in 1985 and went to the playoffs for the first time in their history. It turned out to be Oliver’s last postseason action. In nine plate appearances, he got three hits — including game-winners in Games One and Three — as the Jays lost to the Kansas City Royals. He was unhappy about being pulled for a pinch-hitter in the concluding Game Seven, felt his time in the game was up, and told his wife, “It’s over.”

Indeed, it was the last time Oliver played in the majors. He became a free agent that fall but did not land anywhere in 1986, even though in retrospect he thought he still had plenty left to offer. (He’d produced a .251/.282/.374 batting line for the Jays in 195 plate appearances.) “I could easily have DH’d another four or five years without any problems at the rate that I was going and the condition I was in,” he said in 2017.40

However, Oliver was a victim of conspiracy among major-league teams against free agents after the 1985 season. Eventually, arbitrator Thomas Roberts ruled that the collusion had kept Oliver and nine other players from getting jobs. In January 1995, Roberts awarded Oliver $680,031.41 The award covered only 1986, though, whereas Oliver had requested compensation for 1987 as well.

After announcing his retirement on February 6, 1986, the civic-minded Oliver joined the board of an Arlington organization called “Suicide Is Not Painless,” working with young people to combat the growing societal problem.42

Not long after he retired, Oliver’s marriage to Donna (which had become strained) came to an end. The divorce also caused acrimony with his children for some time, but they eventually mended their relationships. Oliver moved back to Ohio. He lived in Columbus for about a year and a half but then returned to his hometown, Portsmouth. He became active in his community in many ways, establishing the Al Oliver Foundation in 1990. He joined the board of Scioto County Children’s Services in 2008. The county named him a Brand Ambassador in 2013.

The return to Portsmouth also reconnected Oliver with Patricia Harris, with whom he had gone out back in 1965. After dating for five years, they got married on August 16, 1996.

Oliver, who stammered as a child and young adult, overcame that obstacle to become an engaging speaker. That made him a candidate for broadcasting jobs. Two opportunities in Pittsburgh came down to him and one other finalist, but both times he was disappointed. As a result, he closed the book on baseball.

However, he did get back in the game for a while as both player and coach. When the Senior Professional Baseball Association (SPBA) began play in the fall of 1989, Oliver was a member of the Bradenton Explorers. He later served as the first baseball coach at Shawnee State University in Portsmouth.43 He held that position for the 1992 and 1993 seasons (the Bears went 25-33 under him). Shawnee State also held the Al Oliver Classic in 2016 and 2017, but renamed the event in 2018 for another native of the Portsmouth area: Branch Rickey, for whom the university’s baseball park is also named.

Oliver’s main work is rooted in his religious beliefs, as a spiritual and motivational speaker. In 1997, he became a deacon at Beulah Baptist Church, which he had attended growing up.44 He earned his ministerial license in April 2018.45

Oliver became eligible for the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1991, but he attracted just 4.3% of the vote in his first year and thus fell off the ballot. Falling short of 3,000 hits quite likely damaged his case, though even then reaching the milestone might not necessarily have opened the door to induction. In fact, arbitrator Roberts said so specifically in his collusion settlement opinion.

A few years later, the Baseball Writers Association of America (BBWAA) petitioned the Hall of Fame’s board of directors to reconsider the eligibility of Oliver (as well as Larry Bowa, Bill Madlock, and Ted Simmons). The board approved in 1995, but before the 1996 ballot was released, the four players were excluded (further detail is not presently available).46

The first of Oliver’s two autobiographies was published in 1997. It was notable for his willingness to allow some uncomplimentary and critical voices to be heard, “not just creating an echo chamber of ‘Al Oliver should be a Hall of Famer.’”47

When the Hall’s Veterans Committee was revamped in 2001, Oliver gained renewed eligibility.48 He was on the ballot in 2007, 2008, and 2010 but didn’t get anywhere near enough votes. Nonetheless, he has continued to receive attention in discussions of potentially worthy players. He has long viewed himself as deserving fuller consideration, and this is a running theme in his books. The one from 2014 has testimonials from the likes of Pete Rose and Andre Dawson.

Debate was renewed after the announcement in 2018 that Harold Baines would be inducted. There was one especially heated exchange on MLB Network. On one side was Tony La Russa, who managed Baines and was one of the Today’s Game Era committee members who selected him and Lee Smith. On the other was commentator Chris Russo, who expressed the view — held in many quarters — that Baines was not deserving. When asked to compare Baines with Oliver, La Russa replied that Oliver wasn’t better. Russo said otherwise, citing the stats, and an angry La Russa called him clueless. 49

Despite what La Russa had to say about professional evaluation, a look at the numbers supports Russo. Baines and Oliver have identical career OPS+ marks of 121 — good but not great. Oliver scores higher on Baseball-Reference.com’s “Black Ink” and “Gray Ink” metrics, though he is still below the average Hall of Famer on these counts. At the crux of the debate are two ongoing, intertwined issues. Have the Hall’s standards been diluted, and will they erode further? If Player A is in, then why not Player B?

Yet as Oliver responded when members of his congregation suggested that he could become their pastor, “If the call doesn’t come from God, I don’t think it will work out.” But should Cooperstown eventually call, he thinks, “It would give me the platform I need to bring forth positive messages. . .to do what I really believe that God has set out for me to do.”50

Last revised: July 10, 2019

Acknowledgments

Al Oliver’s two books formed the backbone of this story:

Baseball’s Best Kept Secret — co-authored with Andrew O’Toole (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: City of Champions Publishing Company, 1997).

Life Is a Hit; Don’t Strike Out (La Place, Louisiana: VIP Ink Publishing, 2014).

This biography was reviewed by Warren Corbett and Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin. Thanks also to Jonathon Loughridge, Sports Information Director, Shawnee State University.

Additional Sources

Alain Usereau, The Expos in Their Prime (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2014).

www.ssubears.com (Shawnee State University sports website)

Notes

1 Randy Galloway, “Deal Was Best for Me, Oliver Assures Rangers,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1978: 47.

2 Charley Feeney, “More Bucs See of Oliver, More They Like His Hot Bat,” The Sporting News, May 31, 1969: 15.

3 Oliver first spoke this line around 1978, according to Montreal sportswriter Ian MacDonald. “Oliver Finally Reaches the Pinnacle,” The Sporting News, October 11, 1982: 49.

4 George Castle, When the Game Changed, Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press (2011): 45.

5 Oliver recalled the pitcher as Bob Purkey, but Purkey did not become a Red until 1958, and Robinson’s last season was 1956.

6 Charley Feeney, “Oliver Takes Root in Pirate Middle Garden,” The Sporting News, March 20, 1971: 44.

7 Charley Feeney, “Corsairs Strike It Rich with Oliver,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1969: 40.

8 Feeney, “Corsairs Strike It Rich with Oliver,”

9 Feeney, “Corsairs Strike It Rich with Oliver,”

10 Oliver has posted pictures of his father in uniform on Facebook, but here too, further information (years, branch of service, rank) has not yet surfaced.

11 Richard Walker, “Future major league star Al Oliver reflects on the start of his pro career in Gastonia, his “Scoop” nickname and his brush with future greatness,” Gaston Gazette (Gastonia, North Carolina), August 4, 2016 (https://www.gastongazette.com/sports/20160804/future-major-league-star-al-oliver-reflects-on-start-of-his-pro-career-in-gastonia-his-scoop-nickname-and-his-brush-with-future-greatness).

12 “Oliver up to .313,” The Sporting News, September 21, 1968: 32.

13 “Flu Sidelines Columbus’ Leading Hitter, Oliver,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1968: 34.

14 Jerry Roberts, Roberto Clemente: Baseball Player, New York: Ferguson (2005): 71-72.

15 Les Biederman, “Hebner, Robertson Excite Bucs’ Hope for Power Pickup,” The Sporting News, December 7, 1968: 42.

16 Feeney, “More Bucs See of Oliver, More They Like His Hot Bat.”

17 Feeney, “Corsairs Strike It Rich with Oliver.”

18 Jack Lang, “Piniella, Sizemore Prove Persistence Pays,” The Sporting News, December 13, 1969: 34.

19 Ben Henkey, “Prize-Winning Rookies: May and Nagy in A.L., Griffin and Laboy in N.L.,” The Sporting News, November 8, 1969: 34.

20 Charley Feeney, “Platooning Plagues Oliver, but Nut Allergy Is Worse,” The Sporting News, February 12, 1972: 30.

21 Charley Feeney, “Regular Status Stirs Up a Storm in Oliver’s Bat,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1970: 25.

22 Miguel Frau, “Clemente Debuts as Skipper in P.R.,” The Sporting News, October 31, 1970: 55.

23 Charley Feeney, “Virdon, Clemente Okay Oliver for Center Field,” The Sporting News, February 13, 1971: 41.

24 Bruce Markusen, “Thirty Years Ago…The First All-Black Lineup,” BaseballGuru.com, unknown date, 2001 (http://baseballguru.com/markusen/analysismarkusen01.html)

25 Ryan Cortes, “On this day in 1971, the Pittsburgh Pirates fielded the first all-black and Latino lineup,” TheUndefeated.com, September 1, 2016 (https://theundefeated.com/features/on-this-day-in-1971-the-pittsburgh-pirates-fielded-the-first-all-black-lineup/)

26 Charley Feeney, “Oliver’s Value as Buc Keeps Going Up,” The Sporting News, August 20, 1977: 16.

27 Galloway, “Deal Was Best for Me, Oliver Assures Rangers.”

28 Tyler Kepner, “On Uniform No. 0, the Yankees Rule Out Nothing,” New York Times, May 13, 2017.

29 Steve Wulf, “You Don’t Know Me, Says Al,” Sports Illustrated, April 21, 1980. Texas had hoped to reacquire Oscar Gamble from the Yankees (along with Bob Watson and Mike Morgan), but Gamble exercised a partial no-trade clause in his contract

30 Murray Chass, “Gamble Bars Deal; Expos Get Oliver,” New York Times, April 1, 1982: B-12.

31 Dave George, “Oliver Right at Home with Montreal,” Palm Beach Post, April 1, 1982: D1.

32 Tim Raines with Alan Maimon, Rock Solid, Chicago, Illinois: Triumph Books (2017): 79.

33 Charlie Deitsch, “An interview with former Pirates slugger Al Oliver; appearing at PNC Park this weekend,” Pittsburgh City Paper, September 12, 2014 (https://www.pghcitypaper.com/Blogh/archives/2014/09/12/an-interview-with-former-pirates-slugger-al-oliver-appearing-at-pnc-park-this-weekend).

34 Gordon Edes, “Al Oliver: He’ll Tell You He’s Quite a Player and Has Records to Prove It, but He Wants to Hear It From Others,” Los Angeles Times, March 5, 1985.

35 Michael Farber, “Al Oliver: The Expos finally got their man,” Montreal Gazette, June 26, 1982, G-1.

36 Pierre Ladouceur, “C’est le championnat ou les Expos pourraient m’échanger,” La Presse (Montreal, Quebec), May 6, 1983: D6.

37 Jonah Keri, Up, Up, & Away, Toronto: Random House of Canada (2014): 202

38 Frank Dolson, “Phillies obtain Oliver in trade with Giants,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 21, 1984: 41.

39 Edes, “Al Oliver: He’ll Tell You He’s Quite a Player and Has Records to Prove It.”

40 Graham Womack, “Collusion hurt Al Oliver’s Hall of Fame case; can he still get in?” SportingNews.com, March 14, 2017 (http://www.sportingnews.com/us/mlb/news/al-oliver-stats-hall-of-fame-case-montreal-expos-mlb-collusion-1980s/7z0ej4s05c7p1ljnk7srsawtt)

41 “More Collusion Damages Awarded,” Washington Post, January 18, 1995.

42 “Oliver Tackles Unusual Job,” The Sporting News, February 17, 1986: 35.

43 “Al Oliver to Coach Shawnee State,” New York Times, May 1, 1991: B9.

44 Bill Neri-Amadeo, “Al Oliver: A Hall Of Famer On And Off The Field,” Al-Oliver.com, September 18, 2006 (https://al-oliver.com/2018/03/06/al-oliver-a-hall-of-famer-on-and-off-the-field/).

45 Tom Corrigan, “Former MLB player, Portsmouth’s Al Oliver recalls living near site of Pittsburgh shooting,” Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, November 1, 2018 (https://www.portsmouth-dailytimes.com/top-stories/32581/former-mlb-player-portsmouths-al-oliver-recalls-living-near-site-of-pittsburgh-shooting).

46 “Near-fab four may get a break,” New York Daily News, January 8, 1995. There was allegedly a dispute within the BBWAA, according to Jay Jaffe in The Cooperstown Casebook, New York: Thomas Dunne Books (2017):114.

47 Mark Taylor, “Book Review: Baseball’s Best Kept Secret (1997) and Life Is a Hit; Don’t Strike Out (2014), by Al Oliver,” Mark My Words blog, October 2, 2014 (http://mark-markmywords.blogspot.com/2014/10/book-review-baseballs-best-kept-secret.html)

48 Alan Robinson, “Baseball Hall of Fame to reveal all balloting,” Associated Press (Pittsburgh Post-Gazette), August 7, 2001.

49 Dan Caesar, “La Russa fumes in TV interview about his role in Baines’ Hall of Fame selection,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 14, 2018.

50 Womack, “Collusion hurt Al Oliver’s Hall of Fame case; can he still get in?”

Full Name

Albert Oliver

Born

October 14, 1946 at Portsmouth, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.