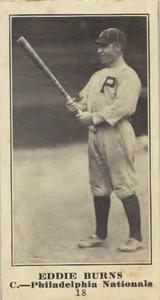

Ed Burns

He began his baseball life as the mascot of his college team, but the diminutive Ed Burns grew into a World Series catcher for the Philadelphia Phillies.

He began his baseball life as the mascot of his college team, but the diminutive Ed Burns grew into a World Series catcher for the Philadelphia Phillies.

On October 31, 18871, in San Francisco, Edward Aloysius Burns and his wife Louisa (née Schaufele) welcomed their only child. Edward James Burns. into the world. The elder Edward was a painter with Irish roots. Louisa, a watchmaker, had both German and French heritage.

Burns’ early baseball development was formed on the San Francisco sandlots and the fields of the coastal paradise of Monterey, about 110 miles south of the city. Per the 1900 Census, Eddie was living in San Francisco with his uncle Richard Burns following the death of his mother in 1891. His father had passed away just a year before Louisa. Burns’ uncle Richard was a tax collector who had been a catcher for the storied St. Mary’s College baseball team in 1886.2 Eddie’s maternal grandparents lived in Monterey. His maternal uncle Harry Schaufele coached Monterey’s town team, the Barracudas (also known as the Stickers) of the on-and-off semipro association known as the California Mission League.

After graduating from San Francisco’s St. Ignatius High School, Eddie matriculated to St. Mary’s, to become a civil engineer and play some baseball. Initially, the 5-foot-6 Burns was the Phoenix’s mascot and played on the school’s seventh team.3 By 1906, he had become the first team left fielder before moving behind the plate the following year. His St. Mary’s teammates included future big leaguers Harry Krause, Duffy Lewis, Charlie Enwright, and future World Series opponent and Hall of Fame outfielder Harry Hooper. Hooper and Burns were pals on and off the field and Hooper was also a former Phoenix mascot. With that kind of talent, it was no surprise that St. Mary’s had a pretty good squad. In fact, the Phoenix went 33-0 in 1907, beating the Chicago White Sox and some Pacific Coast League clubs along the way.4

The Oakland Tribune described Eddie this way: “Burns the catcher is a sort of smallish chap, but he has heroic nerve, and that counts much in baseball. He is a fine thrower to the bases and uses excellent judgment.”5

Following his final season at St. Mary’s, Burns traveled south to play for his uncle Richard, manning several positions for the Barracudas, including catcher and shortstop. However, he would not finish the season in his home away from home.

In late July, Burns signed with the Sacramento Cordovas of the independent California State League.6 “Bill Curtin of Sacramento sent for me and offered me a job playing baseball,” Eddie described. “I laughed at him, for the thought of playing the game for money struck me as funny. Sacramento was only playing Sunday games then, and I wouldn’t think of baseballing until he had promised to find me a position as a civil engineer. Finally, he consented, and it was only the prospect of the outside job that landed me in the game. I really didn’t look on baseball as a serious profession until two of three years afterward.”7

Curtin had caught wind of Burns’ ability from Brother Joseph of St. Mary’s. Brother Joseph reported, “Burns is one of the best all-around men I have ever seen. He shines behind the bat and can be changed to out or infield at a moment’s notice and take good care of any position entrusted to him. He is very strong in batting and was second to Hooper. In the last seven games he has played not a base has been stolen on him. He is a first-class utility man and should prove a grand addition to any team. He excels in the squeeze play.”8

In 119 contests for the 1909 Oakland Commuters12, Burns batted .263, including a professional high eight triples.

Burns began the 1910 season with Oakland, a team that would end the season in the San Joaquin Valley town of Merced. His play in Northern California caught the attention of the Boston Red Sox, who purchased his contract for $1,600. When Sacramento manager Charlie Graham read the news of the transaction in the Sacramento Bee, he wired the American League club asking for Burns’ services for the PCL club. Boston management agreed, providing Graham could get to Burns before he boarded a Boston-bound train. Graham did just that and signed Burns.13 With Sacramento he again played shortstop, as he had in semipro ball. Burns got off to a hot start in California’s capital, going 7-for-18 and scoring three runs in his first four games, but he cooled off considerably to finish the season with just a .182 average in 125 games.

Burns spent 1911 with the Tacoma Tigers of the Class B Northwestern League and had one of the finest seasons of his career. In 150 contests, he batted .253 with 15 doubles and four home runs, both career bests. He would never hit another home run as professional. The Tacoma Times named him to the Northwestern League All-Star team “because of his headwork, pegging to bases and timely hitting.”14

Eddie’s efforts caught the eye of the St. Louis Cardinals. Midway through the 1911 season, the National League club bought Burns and two of his teammates for a total of $11,000. Burns’ price was $2,500.15 However, the Cardinals offered him less money than his Tacoma salary. In Tacoma, Burns made $250 per month. The Cards offered $200. Burns finished the season in the northwest.

Burns returned to California that offseason and found himself with no other playing option other than the amateur Bakersfield “Speed Boys” of the Bakersfield Valley League. He was captain (basically the player/manager) of the team and played third base and caught some games.

On May 8, 1912, after Burns had filed a formal complaint, the National Baseball Commission ruled that St. Louis would pay Burns his salary dating from April 11 at an increase of 25% above his 1911 Tacoma wage.16 Burns figured he would now be waiting for his release, but instead the Cardinals called him up and he boarded a train for St. Louis on May 17.17 When he arrived, the Cardinals already had five catchers on the roster, including player-manager Roger Bresnahan.18

Burns rode the bench, seeing his only game action on June 25, when he entered a game against Pittsburgh as a defensive replacement in the top of the seventh inning. He went 0-for-1against Pirates righty Claude Hendrix, reaching base on an error by Bill McKechnie in the seventh inning of a 10-4 loss at Robison Field. He left the game in the ninth inning for a pinch-hitter.19

In July he was sent north of the border to the Montreal Royals of the Double-A International League. He found much more playing time and success in Quebec. Over 52 games, he batted .273 with eight doubles and three triples.

Burns returned to Montreal to begin 1913. In 95 games with the Royals, he banged out 12 doubles and five triples and hit a personal best of .295. He saw the Montreal experience as key to getting to the majors. In Burns’ view, the scouts of the day were much more attentive to the goings-on in the eastern-based International League, compared to the PCL. As he told the San Francisco Chronicle in 1915, “I know in my case that if I had been sent to the Coast League, I would not have returned so quickly to the big league. The Coast League is so far away that the majors do not go to the expense of sending out scouts and a lot of promising material is overlooked.”20

On August 29, 1913, Burns was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for Dan Howley and a reported $10,000. The following day at the Baker Bowl, he was in the starting lineup catching Pete Alexander. This game is an infamous classic. Alex the Great was ineffective and was forced to leave the game after just three innings. Burns notched his first big-league hit, leading off the seventh with a line-drive single to right against another future Hall of Famer, Christy Mathewson of the New York Giants. Though Burns was forced at second, the Phillies rallied to take a 6-5 lead.21

In the top of the ninth inning with Philadelphia leading, 8-6, umpire Charles Brennan ruled the game a forfeit in favor of the Giants. Brennan had noticed Phillies rooters in the centerfield bleachers were wearing white shirts with no coats or jackets. Brennan thought the rooters were preventing batters from properly seeing the ball. When Brennan couldn’t get Philadelphia management or the police to remove the fans, the forfeit was declared.

After the game, a reported “thousands” of Philadelphia fans followed the Giants and Brennan to the North Philadelphia Train Station. The police, even with pistols drawn, could not hold the crowd back. Brennan was beaten by fans and Giants third baseman Tillie Shafer was hit behind the ear with a brick.22 Brennan’s ruling was overturned, and Philly was credited with an 8-6 win.

At Ebbets Field on September 1, Burns’ RBI single capped Philadelphia’s three-run, seventh inning rally in a 3-2 victory over the Brooklyn Superbas. In the season finale, Burns doubled twice to finish with a .200 batting average in 17 games. He never returned to the minors, spending the next five seasons with the Phillies, primarily backing up starter Bill Killefer.

On June 26, 1914, at Brooklyn, Burns notched his first three-hit game in the majors. He was batting .441 at the time but played only sparingly behind Killefer and player-manager Red Dooin, both excellent defenders. By season’s end, Burns had appeared in 70 games for sixth-place Philadelphia, batting .252 with four triples and five stolen bases in 139 at-bats. He struck out only 12 times and drew 20 walks for an above-average .352 on-base percentage.

In 1915, Burns got into 67 games, hitting .241 and driving in 16 runs. An injury to Killefer put Burns in the spotlight. Killefer fell victim to a dead throwing arm in early September. According to Baseball Magazine, “there were no torn muscles or ligaments, but the arm lost its strength.”23

Beginning on September 8, the Phillies went 19-4 with Burns behind the plate to clinch the NL pennant. Philadelphia summoned a doctor from New York to examine Killefer’s arm before the World Series, but it had not improved enough for him to play.24 Consequently, the full-time catching duties stayed in the hands of Burns.

When the Boston Red Sox came to the City of Brotherly Love for Game One of the World Series on October 8, Burns caught baseball immortal Grover Cleveland Alexander. After posting a 31-10 regular-season record for the 90-62 Phillies, Old Pete handled the Sox, 3-1, on an eight-hitter. Burns batted eighth and, although he went 0-3 with a strikeout, his glove likely saved a run in the second inning when he handled a tricky, wild Alexander offering with a runner at third.

The next day President Woodrow Wilson and his fiancée Edith Bolling were on hand as Erskine Mayer, a 21-game winner, took the mound for Philadelphia. In another tight affair, Rube Foster pitched the visitors to a 2-1 victory as Burns went 0-for-3 again.

In the first inning, Burns also committed Game Two’s only error. With Boston’s Harry Hooper and Tris Speaker on third and first base, respectively, Burns threw out the latter attempting to steal second. Initially, it looked like a big baserunning mistake when Hooper made a late break for the plate. However, Philadelphia second baseman Bert Niehoff’s hurried throw home wound up in the dirt near Burns’ feet. Burns was charged with the error as he was judged to have failed to field the ball cleanly, preventing him from controlling the ball in time to tag his sliding former St. Mary’s teammate.25 Boston prevailed, 2-1, to even the series.

Burns and Hooper were not the only St. Mary’s alums in the 1915 Fall Classic. Sox outfielder Duffy Lewis, pitcher Dutch Leonard, and Phillie tosser Joe Oeschger were also in uniform.26

In Boston, the Red Sox won Games Three and Four by identical 2-1 scores to seize control of the best-of-nine series. Burns scored Philadelphia’s only run in Game Three. After leading off the third frame with a single off Leonard, he advanced to second on an error and went to third on a sacrifice bunt before scoring following Dave Bancroft’s single over second base.

In Game Four, Burns singled to right field in three trips and drew an intentional walk. From behind the plate, he gunned down Speaker again when the Sox star attempted to steal second in the first inning. He also helped turn a 1-2-3 double play to end the eighth inning and keep the Phils within one run of the lead.

Back in Philadelphia on October 13, Burns did his best to keep the Phillies in contention from both behind the plate and at bat in Game Five. He threw out Speaker for a third time and stroked an RBI single in fourth inning to put the Phillies up 4-2. Lewis’s two-run homer in the eighth tied the contest, however, and Hooper’s solo four-bagger an inning later gave the Red Sox a 5-4 advantage. The Series ended with Burns and Killefer (making his only series appearance as a pinch-hitter) grounding out against Foster, as the Phillies suffered their fourth straight one-run defeat. Burns’ .188 batting average in the series was a little better than Philadelphia’s overall .182 team mark.

Back in Monterey, by then Burns’ hometown, the catcher was seen as a hero despite the World Series loss. It was not just his hometown that held Burns’ play in high esteem. A Brooklyn retrospective later stated, “The catching of Eddie Burns for the Phillies was of the highest order throughout the series . . . He proved of sterling worth and will long be remembered by those who saw him work.”27

In addition to the news and excitement of the series, October 9 also brought the announcement to Monterey area locals that Burns would be marrying Monterey’s own Viola La Porte.28 Viola was a descendent of one of Monterey’s founding Spanish colonial families. Indeed, her grandfather was the Spanish Royal governor.29 Burns had met LaPorte for the first time 12 years earlier on one of his regular visits to Monterey and the Schaufele family. Eddie and Viola later had two sons, Ed, Jr. and John, and a daughter, Carmelita.

An article in the Monterey Daily Cypress mentioned that “Old Pete” Alexander himself was to possibly come to Monterey for the wedding.30

Prior to his nuptials, Burns barnstormed as a member of Oscar “Ossie” Vitt’s All-Stars. Vitt, a third baseman for the Detroit Tigers, was also a former Monterey Barracuda. On October 29, the San Francisco Seals beat the All-Stars 8-7 in San Francisco. Perhaps Burns was thinking more about his wedding that day – the Seals stole seven bases.31

The wedding was held at San Francisco’s Sacred Heart Church. No evidence of Alexander’s attendance is recorded, but another St. Mary’s alum and former St. Louis Brown, Edward Hallinan of the PCL’s Salt Lake Bees, was there.32

The Phillies’ 1916 season began with Killefer’s arm still not fully mended. The newly married Burns started the first 18 games, including a 2-for-4 performance in catching Alexander’s Opening Day victory over the Giants. Work like that helped move his average to .304 by June 26, but he struggled through a .180 second half. Overall, in a major-league high 78 games, Burns batted .233.

In 1917, Burns broke a bone in his thumb early in the season and saw action in just 20 games. After the season, the Phillies traded Killefer to the Cubs and Burns must have thought the 1918 season would bring great things. That campaign started out with Burns as the Phillies’ top catcher up until July 27. He abruptly resigned from the club at the end of July, having played in 68 games and batting .207 with a mere two extra base hits – his OPS was barely .500. Reportedly, there were multiple factors that led to his decision, including the instability of baseball as a career, overall performance, comparisons to the traded Killefer, homesickness, and the illness of his father-in-law.33

The Phillies still held the rights to Burns in 1919 and tried to sell him to the San Francisco Seals. Burns, however, indicated that he was done with professional baseball and ready to begin a career in the business world in Monterey.

Burns left the game with a reputation as a solid defensive catcher with a weak bat. In his six seasons with the Phillies, Burns played in 320 games, collecting 183 hits, and driving in 64 runs. He never hit a major-league home run. Only once in his career was Burns a league average hitter, and that was 1914. His OPS dipped every year after that. Despite this, history shows Burns playing well down the stretch of the 1915 season, helping to get the Phillies into the World Series, and his remarkable defensive play in that series, which included throwing out six of seven would-be base stealers in five games.

Back in Monterey, Burns went into partnership with Bernard Druck, forming Druck and Burns men’s clothiers.34 In 1921, Druck passed away and the business became the Eddie Burns Clothes Shop. The store was located on Monterey’s historic Alvarado Street. It remained a going concern throughout Burns’ life.35

Though he was done with pro baseball, Burns the store owner and community member took to local fields with Mission League clubs like Hollister from time to time. In 1921, when the San Francisco Seals came to Monterey for spring training, Burns was behind the plate when the locals took on the Seals. It was a tough day for the Barracudas as they fell 9-0 to the PCL club. Burns was 0-2 at the plate.36

Burns was an avid golfer, skeet shooter, and hunter. To stay close to baseball, he umpired local games, coached the Monterey Elks Club team, and even briefly led the Barracudas. In March 1934, he was offered the chance to be president of the Mission league. He turned down the offer and recommended Harry Hooper (then the postmaster of Capitola, California) for the job.37 Hooper didn’t take the job either; it went to hotelier Bill Jeffrey.

Burns also found time to serve on the Monterey City Planning Commission, where he was instrumental in developing the city’s zoning regulations.38

Ed Burns passed away on May 30, 1942, after suffering a heart attack (his son John was serving in the U.S. Army at the time of his father’s death). He is buried in Monterey’s historic San Carlos Cemetery.39

Last revised: September 28, 2021 (zp)

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied primarily on newspaper articles found at newspapers.com and details from Ancestry.com (see Notes section below). In addition to the sources cited in the Notes section, the author also consulted the following:

Zingg, Paul. Harry Hooper: An American Baseball Life. Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 52-53, 139.

Zingg, Paul and Medeiros, Mark. Runs, Hits, and an Era: The Pacific Coast League, 1903-58. (Urbana and Chicago, Illinois: University of Illinois Press, 1994), 14.

Unless otherwise noted, statistics have been taken from Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

2 C. P. Beaumont, “A Training School for Baseball Stars,” Baseball Magazine XVIII, no. 1 (1916): 73-76.

3 “How Baseball Stars are Developed at St. Mary’s,” Salinas (California) Daily Index, April 17, 1911: 1.

4 Vincent de Paul Fitzpatrick, “Then Conquer We Must,” Tablet (Brooklyn, New York), July 11, 1942: 10.

5 T.P. Magilligan, “St. Mary’s Ball Tossers Have No Peers on American Diamond,” Oakland Tribune, February 17, 1907: 4.

6 “‘Babe’ Burns to Catch Brown Tomorrow,” Evening Bee (Sacramento, California), July 20, 1907: 16.

7 Fred A. Purner, “Eddie Burns One Player Who Had No Big League Ambition,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 17, 1915 :52.

8 “New Catcher for the Local Team,” Evening Bee, July 17, 1907: 9.

10 “Eddie Burns Jumps the Alameda Team,” Sacramento Bee, June 12, 1908: 20.

14 F.K. Brown, “Burns, Bues, Bennett, and Cooney Are Favorites in All-Star Team,” Tacoma (Washington) Times, September 23, 1911: 2.

15 “Eddie Burns Sold: Going to St. Louis,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 29, 1911:10.

16 “Eddie Burns’ Victory Makes Baseball History,” Bakersfield (California) Californian, May 8, 1912: 5.

17 “Eddie Burns off to St. Louis on the Santa Fe Tomorrow,” Bakersfield Californian, May 16, 1912: 5.

18 “Roger Now Has Five Catchers.” St. Louis Post Dispatch, May 22, 1912: 9.

19 Ed F. Balinger, “Pirates Take Two Games and Again Land in Second Place,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 26, 1912: 3-1.

20 Fred A. Purner, “Eddie Burns One Player Who Had No Big League Ambition,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 17, 1915 :52.

22 “Phila Rooters Mob Ump Who gave N.Y. Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 31, 1913: 1.

23 J.C. Koefed, “The Brainiest Catcher in the National League, Baseball Magazine XVIII, no. 1 (1916): 65-67.

24 “Fans Waiting for Tickets; Eddie Burns May Catch,” Sacramento (California) Bee, October 7, 1915: 12.

25 “Foster is Hero in Second Game,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 10, 1915: 68.

26 Fitzpatrick, “Then Conquer We Must.”

27 Fitzpatrick, “Then Conquer We Must.”

28 “Eddie Burns to Marry Viola LaPorte of Monterey,” Monterey Daily Cypress, October 10, 1915: 1.

29 “National League Catcher to Wed,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 24, 1915: 13.

30 “Eddie Burns to Marry Viola LaPorte of Monterey,” Monterey Daily Cypress, October 10, 1915: 1.

31 “Vitt’s All Stars are Beaten by Frisco Team,” Fresno (California) Morning Republican, October 29, 1915: 14.

32 “National League Catcher to Wed,” San Francisco Chronicle, November 24, 1915: 13.

33 “Eddie Burns Not Appreciated by Philly Fandom,” Pittsburgh Press, August 8, 1918: 23.

34 “Eddie Burns will Quit Baseball,” Monterey Daily Cypress and Monterey American, February 14, 1919: 1.

35 “Announcement,” Monterey Daily Cypress and Monterey American, October 7, 1921: 2.

36 “Monterey Badly Outclassed by Seals,” Salinas Californian, March 14, 1921: 6.

37 “Burns Unable to Take Mission Job, Suggest Cruzano,” Salinas Morning Post, March 11, 1934: 6.

38 Fitzpatrick, “Then Conquer We Must.”

39 “Death Takes Eddie Burns,” Salinas Californian, June 2, 1942: 1.

Full Name

Edward James Burns

Born

October 31, 1887 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

May 30, 1942 at Monterey, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.