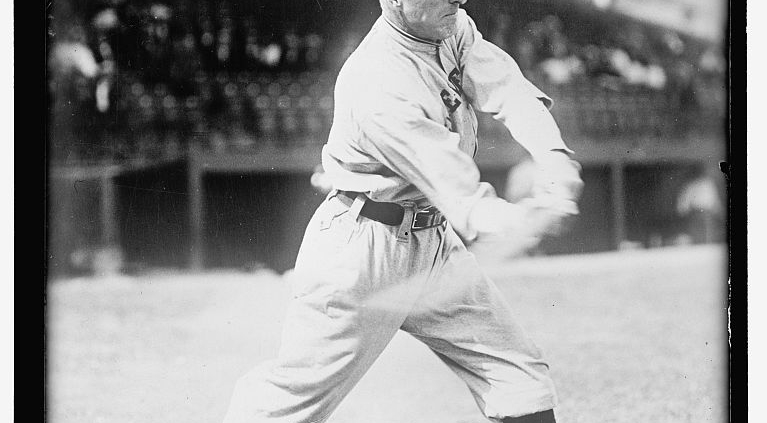

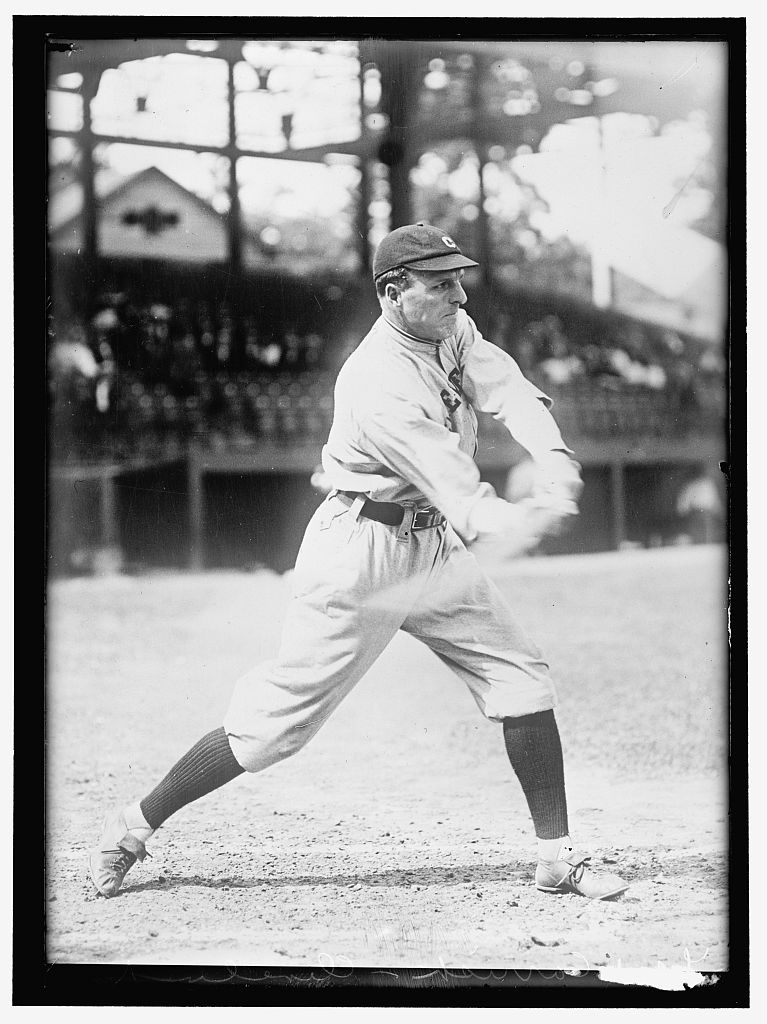

Fred Carisch

Eccentric behavior, particularly when it came to fast cars, a disdain for off-season training, and bad luck with injuries limited Fred Carisch to parts of eight major-league seasons as a backup catcher in the early 20th century. However, he remained in the game for more than two decades – indeed, his first and last games in the majors came nearly 20 years apart – mostly thanks to his reputation as an expert handler of pitchers. It was once said, “One of Fred Carisch’s strong points as a backstop is his ability to steady his pitchers when balls thrown wide of the plate show that they are wavering. When a pitcher shows the first symptoms of looseness in his delivery, Carisch immediately ‘shakes’ or ‘holds’ them up, bringing them back to their natural delivery.”1

Eccentric behavior, particularly when it came to fast cars, a disdain for off-season training, and bad luck with injuries limited Fred Carisch to parts of eight major-league seasons as a backup catcher in the early 20th century. However, he remained in the game for more than two decades – indeed, his first and last games in the majors came nearly 20 years apart – mostly thanks to his reputation as an expert handler of pitchers. It was once said, “One of Fred Carisch’s strong points as a backstop is his ability to steady his pitchers when balls thrown wide of the plate show that they are wavering. When a pitcher shows the first symptoms of looseness in his delivery, Carisch immediately ‘shakes’ or ‘holds’ them up, bringing them back to their natural delivery.”1

Frederick Behlmer Carisch was born on November 4, 1881, in Fountain City, Wisconsin. His parents were Anna (Behlmer) and Christopher Carisch. Christopher, a native of Switzerland, came to the United States as a toddler. Anna, the daughter of Prussian immigrants, was born in Wisconsin. Christopher worked as a warehouse laborer at the time of the 1880 US Census but by the early 1900s had established a harness business, C. Carisch & Sons, in nearby Alma, Wisconsin.2

Fred grew up with older brothers George and Edward; an older sister, Lena; and a younger brother Emil. Fred’s mother, Anna, died in 1887 when he was a young boy, and his father married Mary Andres two years later They had two daughters, Frances and Alice. Around this time the family moved to nearby Alma, where Fred was raised.

Both of Fred’s older brothers, George and Ed, were ballplayers. George pitched professionally in the Western Association in the mid-1890s. Ed was also a pitcher, and Fred started out catching his brothers on local amateur teams. The first press reports of the “Carisch brothers battery” were from 1899 with an amateur team in Hastings, Minnesota.3 By 1901 Fred had caught the attention of George Lennon of the St. Paul Saints of the Western League. He was signed to a professional contract in April of that year.4

Found not yet ready for the Western League, Carisch was released by the Saints in late May.5 Later that summer he briefly played shortstop for a club in Fort Dodge, Iowa. In 19026 Carisch hooked on with a semipro club in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, members of the Class D Iowa-South-Dakota League, as a right fielder and change catcher. In July Carisch entertained an offer from the Des Moines Western League club, which invited him to “name his own terms.”7 However, Carisch declined the offer and finished the 1902 season in Sioux Falls.

That fall Carisch was drafted by Denver of the Western League, but there was also interest from the Chicago National League club.8 Around the same time, Helena, Montana of the Pacific National League began negotiations for his services. He eventually signed with Helena but because Denver held his contract rights, the National Board of Arbitration ruled that Helena had to pay Denver $300 to secure his release.9 In Helena he reunited with his brother George, who was signed as a pitcher.

Carisch had an excellent season with Helena in 1903, batting .310 in 103 games before the team disbanded in early August. He and pitcher Gus Thompson were signed by the Pittsburgh Pirates and sent train fare east. A couple of years later, Pirates manager Fred Clarke told the story of how the signing took place. Clarke and Pittsburgh owner Barney Dreyfuss had been scouting Thompson for some time and bought his release from Helena for $500. At the time of the transaction, Helena manager Jack Flannery told the Pittsburgh men that one reason for Thompson’s success was a promising young catcher named Carisch. According to Clarke, “If we had no objections, Carisch would report with Thompson – the Helena club would throw him in for good measure. We told them to send him along.”10

Pittsburgh, the defending National League champion, was a formidable team. Led by shortstop Honus Wagner, third baseman Tommy Leach, outfielders Ginger Beaumont and Fred Clarke, along with a pitching staff headed by 25-game winners Deacon Phillippe and Sam Leever, the Pirates would repeat as pennant winners with a 91-49-1 record. When Carisch and Thompson joined the club in late August, the Pirates held a comfortable nine-game lead over the second-place New York Giants. The rookies watched the first few games from the dugout in “open-eyed wonder at the cleverness of the men.” They were most impressed with the reception by Wagner, “who told them that if there was anything about the game they wanted to know, just to call upon him.”11

The rookie battery made their major-league debut on Monday, August 31 before 678 fans at Robison Field in St. Louis against the Cardinals. Carisch had two hits, both doubles, and Thompson allowed just six hits in a 9-6 complete game Pirate victory. Carisch didn’t see any action for nearly three weeks, but once the pennant was clinched, he appeared in four more games that season. He hit another double and recorded his first major-league RBI and run scored in a 12-10 win over the Brooklyn Superbas in the first game of a September 19 doubleheader. Two days later also against Brooklyn, he homered and knocked in two runs. Overall Carisch hit an impressive .333 (6-for-18) in his first taste of major-league ball. He stayed with the club as a bullpen catcher but was not on the active roster during the World Series against the Boston Americans.

Carisch returned to Pittsburgh in 1904 but found little playing time behind starting catcher Ed Phelps and main backup Harry Smith. He got into only 22 games behind the plate and filled in at first base for 14 more before a bout of typhoid fever ended his season prematurely in late August. He was hospitalized for a time at Allegheny General; at one point, it was reported that “the doctors are somewhat concerned about his condition.”12 He eventually recovered and spent the off-season working with his father and brothers in the harness shop back in his home in Wisconsin.

The 1905 Pirates had another outstanding season, eventually finishing second to the Giants in the National League pennant race. That off-season the Pirates traded Phelps to Cincinnati for veteran catcher Heinie Peitz, so Carisch opened the season as the team’s third catcher, behind Peitz and his primary backup, George Gibson. Carisch was sidelined for nearly a month with an undisclosed illness (possibly a recurrence of typhoid fever) but rejoined the team late in the season. He hit .206 in 32 games but did make one major contribution to the team. He recommended Homer Hillebrand, against whom Carisch had played in the west, to Dreyfuss and advised the Pirates owner to sign him.13

With Gibson having established himself as the starting catcher, Peitz still available as a backup, and the return of Phelps in May, there was no room or Carisch on the 1906 Pirates roster. After four early season games he was sold to Rochester of the Eastern League in mid-May.14 His play in Rochester over the rest of the 1906 season kept Carisch on the radar of major-league teams; he was signed by Connie Mack of Philadelphia in February 1907.15 Already stocked with seasoned catchers Osee Schrecongost and Doc Powers, Mack optioned Carisch to Newark of the Eastern League soon after signing him.16

Carisch refused to report to Newark (brother Edward died that February, so that may have been a factor). Giants manager John McGraw also expressed interest in Carisch and tried to acquire his rights from Newark.17 When that deal fell through, Carisch ended up all the way out in Pullman, Washington, where his brother George was the proprietor of a saloon. Fred played on a local amateur team and married Helen Heslin, a native of Wisconsin, in Spokane on June 12, 1907. Tragically, Mrs. Carisch died of “brain fever” in October of that year.18

Newark still held his rights, so Carisch – after at one point threatening to quit baseball for good – accepted terms and reported to the Indians in the spring of 1908. He batted just .131 in 25 games and the following spring was sold to St. Paul of the American Association. Carisch rebounded with a strong season, batting .257 in 118 games for the Saints, but was on the move again that off-season when manager Mike Kelley traded him to Columbus for outfielder Josh Clarke.19 One reason for the departure from St. Paul may have been a disagreement with Kelley over the use of his automobile. It seems Carisch had a habit of commuting “at a high rate of speed” the 30 miles to his home in Hastings, Minnesota after home games. The trips usually involved three or four teammates and Kelley worried whether the players would return safely for the next day’s game. As a result, Kelley issued an ultimatum, directed specifically at Carisch, forbidding his players to own or operate automobiles.20

Carisch initially refused to report to Columbus in the spring of 1910 and again threatened to quit baseball for good. He was quoted as being satisfied with his contract but that a “business proposition” might delay his arrival or prevent him from coming to Columbus at all.21 The business proposition apparently did not pan out: Carisch eventually reported to Columbus. He was having a strong season when he was sidelined for a month with a broken finger. He returned late in the year, but when Columbus made a deal to acquire Cleveland’s veteran catcher Harry Bemis that off-season, Carisch became expendable.

Columbus sold him to Indianapolis in February 1911.22 From his home in Wisconsin, Carisch – 20 pounds overweight and described as “madder as the time flies”23 and “sore” at being sold to the Indians – again threatened to quit baseball. However, as had been his habit, he relented and joined Indianapolis. After starting out as one of the top batters in the American Association, he sustained another hand injury, this time a dislocated thumb. When a shift to the outfield proved unsuccessful, Indianapolis released him in June.24

Carisch was quickly picked up by Toledo, his fourth American Association team in three years. Noting his injury history, at the time of his signing with Toledo the Columbus Dispatch sarcastically remarked, “He [Carisch] will make a good man for a month at least, and longer if he doesn’t get hurt.”25 Carisch managed to remain healthy the rest of that season and most of the next. By mid-season, 1912, he was considered the second-best catcher in the American Association, second only to Ray Schalk of Milwaukee. So, even though he was hitting just .249, in mid-August the Cleveland Indians sent their backup catcher Paddy Livingston to Toledo26 and called Carisch up to the big club. Just like that, after an absence of more than six years, Carisch was back in the major leagues.

He played regularly over the next month, getting into 24 games between August 14 and September 20. His best day as a major-leaguer was a five-hit performance that included a double and triple against the Red Sox on September 17. Overall, Carisch batted a respectable .275 in his late season call-up. However, the injury bug struck again when he chipped a bone in his hand in late September, ending his season. To wrap up his year, Carisch married Verna May Jones in November; the couple spent their honeymoon in Pasadena, California. His hand having healed, Carisch stayed in the west and played for San Diego in the California Winter League.

As Carisch entered spring training with Cleveland in 1913, young Steve O’Neill emerged as his primary competition for the starting catcher’s position. As the season unfolded, the two receivers ended up splitting the catching duties, O’Neill appearing in 80 games behind the plate and Carisch in 79. Carisch batted just .216 with six extra-base hits but excelled defensively. His 51.4% caught stealing rate was second best in the American League, he was third among league catchers with 10 double plays, and his 309 putouts ranked fifth.

In January 1914 Carisch turned down a reported offer of an $5,000 annual salary from Kansas City of the Federal League.27 When Indians teammate Cy Falkenberg jumped to the Hoosier Feds, he tried to induce Carisch to join him. Carisch rejected that offer as well and re-signed with Cleveland.28 He opened the 1914 season as the Indians’ regular catcher, appearing in 29 of the team’s first 41 games. But, by early June a slump brought his batting average down to .200 and O’Neill supplanted him as the starter. After going hitless in three at-bats on June 1, Carisch appeared in just 12 more games all season.

By early August, with the team mired in last place in the American League standings, Carisch was one of several Indians put on the trading block. Team president Charles Somers intended to “weed out some of the troublemakers,” among them longtime second baseman Nap Lajoie, first baseman Doc Johnston, utility man Ivy Olson, and Carisch.29 Supposedly, this four-man clique opposed manager Joe Birmingham. A three-way deal involving St. Louis and the New York Americans was discussed but the trade never materialized.30

Carisch was given his unconditional release by Cleveland in February 1915 and landed on his feet with the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. Portland manager W. W. McCredie previously knew of Carisch because he’d played with his brother George in Quincy, Illinois back in 1898. Carisch had a good season with Portland, batting .268 before having his season end early in September with still another injury, two broken fingers from a foul tip.

While in Portland that summer, Carisch had another incident involving an automobile. After having his Velle shipped out midseason, he was pulled over for speeding at 32 miles per hour by a motorcycle patrolman. Carisch claimed he couldn’t know how fast he was going because the light illuminating his speedometer wasn’t working.31 The presiding judge fined him $10 and, because of the poor season the Beavers were having, admonished him to “put some of the speed you were burning up the turnpike with into your play.”32

Carisch and McCredie could not come to terms on a contract for 1916, so he was given his unconditional release in February. He quickly hooked on with the independent Tri-Copper League in Arizona, and by October accepted his first job as manager in Hayden, Arizona. He returned to Hayden in 1917 and built a strong team by signing several ex-Pacific Coast League players.33 In 1918 Carisch took the manager’s job (while continuing to catch on occasion) in Tyrone, New Mexico.34

Carisch moved to Hibbing, Minnesota late in 1919, possibly because of his friendship with Newt Randall, who was playing independent ball there at the time.35 By the time of the 1920 US Census, he and his wife were living in Minneapolis, where Fred worked as an auto truck mechanic. Later that year he was hired as player-manager in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, where he had begun his career two decades earlier. He led Sioux Falls to second-place finishes in the Class D Dakota League in 1920 and 1921 and returned in 1922. Carisch made his off-season home in Sioux Falls, where he worked as an automobile salesman, first selling Studebakers and later Reo cars.36 While at the helm in Sioux Falls, his eye for talent, especially for pitchers, resulted in sales of several of his players, including George Stueland,37 Willie Ludolph,38 and Hi Bell to major-league organizations.

Ty Cobb took over as manager of the Detroit Tigers in 1921 and one of his coaches was Dan Howley. When Howley accepted a job as manager with Toronto of the International League in 1923, Cobb hired Carisch as a coach to replace him, specializing in working with young pitchers and catchers.39 When the Tigers began spring training in Augusta, Georgia, one of the players assigned to work with Carisch was left-handed pitcher Roy Moore. Cut loose by Connie Mack in Philadelphia after a 1-13 record in 1921, Moore was invited to the Detroit spring training camp and Carisch advised him to lengthen his stride to gain better control.40 Initial results were positive, but they did not take. Moore never won another game in the major leagues.

While a member of the Tigers coaching staff in 1923, Carisch got into two more major-league games. The first was when he caught the last inning of a 16-1 blowout of the St. Louis Browns on April 21; his final appearance came in the morning game of a July 4 doubleheader against the Indians in Cleveland. In the Tigers’ fourth inning, backup catcher Larry Woodall pinch-hit for starter Johnny Bassler and stayed in the game. The teams were deadlocked at seven each when in the top of the 10th inning Woodall was ejected by base umpire Pants Rowland for arguing a call at second. The only other player on the roster with catching experience, Clyde Manion, had been used as a pinch-hitter earlier in the game.41

Still tied at seven, the Tigers had no one available to catch the bottom of the inning. Both Bobby Veach and Del Pratt volunteered to go behind the plate – but player-manager Cobb, who also had been thrown out earlier in the game and was now sitting in the grandstand – ordered Carisch to catch. Cleveland manager Tris Speaker immediately lodged a protest with home plate umpire Billy Evans on the grounds that Carisch was an ineligible player. When the Indians scored three runs in the bottom of the inning to take a 10-7 win, Speaker withdrew his protest.42

Carisch returned as one of Cobb’s coaches again in 1924 and got one more chance to manage. The Tigers were scheduled to end the season on Sunday, September 28 in Chicago. The teams played to a 10-10 tie, so they had to play again the following day. Cobb “took the night train for Detroit Sunday and left the boys flat to take care of themselves.”43 Carisch was placed in charge of the team that was “sore about having to play a game.” They merely went through the motions in a farcical 16-5 loss. Thus, Carisch’s career major-league managerial record is 0-1.

As the Tigers prepared for spring training in 1925, the catching duo of Bassler and Woodall was considered a team strength, but an area that needed shoring up was the middle infield defense. Therefore, former major-league shortstop George McBride was hired as a coach and Carisch was let go.44 He retired from baseball and worked as an auto and truck salesman in Detroit for the next 20 years. Carisch was still in Detroit in 1950 as he placed a classified ad trying to sell a 1949 four-door Buick Roadmaster.45

Fred’s wife Verna died in 1952; sometime after that, Carisch moved back to his native Wisconsin. By 1955 he was living with his brother-in-law in Madison,46. He still followed the game closely, attending Braves games in Milwaukee when he could, and he became known as Madison’s number one sports fan.47 He caught up and reminisced with his old teammate Honus Wagner at an old-timers game but was too ill to attend the 50th anniversary of the Pirates’ 1903 World Series team.

Carisch moved to southern California late in life and married a third time, in 1967, to Mildred Lillian Juran, when he was 85 years old. In 1975, at age 93, he was given a plaque in recognition of being the oldest living Detroit Tiger.48

Fred Carisch died two years later, on April 9, 1977, in San Gabriel, California, at the age of 95. He was buried at Rose Hills Memorial Park in Whittier, California. He left his widow Mildred but had no known descendants.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Paul Proia,

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics from Carisch’s playing career are taken from Baseball-Reference.com, and genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com. The author also used information from clippings in Carisch’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 “Holding Up a Pitcher,” Indianapolis News, April 22, 1911: 10.

2 “Local Items,” River Falls (Wisconsin) Journal, November 21, 1901: 6.

3 “Hastings Was at Home,” St. Paul Globe, July 31, 1899: 6.

4 “Carisch Goes to St. Paul,” Minneapolis Times, April 16, 1901: 2.

5 “President Hickey’s Official Bulletin,” St. Joseph (Missouri) Gazette, May 6, 190: 5.

6 “Score Was 2 To 0,” Daily Argus-Leader (Sioux Falls, South Dakota), August 12, 1901: 3

7 Sioux Falls Argus Leader, July 17, 1902: 8.

8 Sioux Falls Argus Leader, October 6, 1902: 7.

9 “Offer or Fred Carisch,” Los Angeles Times, April 17, 1903: 3.

10 “Gossip About the Players,” Seattle Times, May 4, 1905: 7.

11 “Surprised Newcomers,” Pittsburg Press, September 1, 1903: 10.

12 Pittsburgh Weekly Gazette, September 10, 1904: 9.

13 “Pirates’ New Player,” Pittsburg Post, March 3, 1905: 9.

14 “Catcher Carisch Is Sold to Rochester,” Pittsburg Press, May 18, 1906: 6.

15 “Fred Carisch in Mack’s Squad,” Rochester (New York) Democrat and Chronicle, February 11, 1907: 14.

16 Carisch Goes to Newark,” Washington (DC) Herald, February 23, 1907: 9.

17 Giants After Fred Carisch,” Pittsburg Press, April 18, 1907: 1.

18 River Falls (Wisconsin) Journal, October 17, 1907: 6.

19 “Josh Clarke to St. Paul,” Minneapolis Star, March 0, 190: 17.

2020] “Cut Out Autos,” Lincoln (Nebraska) Star, January 14, 1910: 11.

21 “Carisch May Quit Baseball or Good,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, March 1, 1910: 11.

22 “Carisch Sold to the Indians,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 5, 1911: 29.

23 Baseball Storiettes,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, March 3, 1911: 19.

24 “Carisch is Released to Make Room or Toledo Outfielder,” Indianapolis Star, June 1, 1911: 9.

25 Columbus Dispatch, June 7, 1911: 13.

26 Cleveland had an informal working relationship with Toledo.

27 “Carisch of Naps Rejects Federals,” Macon (Georgia) News, January 9, 1914: 5.

28 “Fred Carisch Signs Up,” Pittsburgh Post, January 30, 1914: 13.

29 “Browns, Yanks, and Naps Are Dickering,” Washington (DC) Herald, August 5, 1914: 31.

30 “They Are on the Auction Block,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, August 5, 1914: 2.

31 “Carisch Fined for Speeding on Road,” Portland (Oregon) Journal, August 17, 1915: 13.

32 “Advice to Catcher,” Pomona (California) Progress, August 18, 1915: 10.

3333] Carisch Will Have Strong Aggregation,” Arizona Copper Camp (Ray, Arizona), March 3, 1917: 2.

34 Hayden Notes,” Arizona Copper Camp, April 6, 1918: 5.

35 “Fred Carisch Will Make His Home in Hibbing,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, September 8, 1919: 10.

36 “Fred Carisch to Sell Reo Cars this Winter,” Sioux Falls Argus-Leader, September 1, 1921: 3.

37 “Stueland to Leave Feb. 15,” Daily Argus-Leader, February 7, 1922: 11.

38 “News and Views by Sesh,” Daily Argus-Leader, July 26, 1923: 5.

39 “Fred Carisch to Coach Ty Cobb’s Pitchers,” Chattanooga (Tennessee) Times, December 11, 1922: 7.

40 “Connie Mack’s Castoff May Be Tiger Star,” The Herald-Palladium (Benton Harbor, Michigan), March 31, 1923: 5.

41 “Tigers-Indians win One Apiece”, Battle Creek (Michigan) Enquirer, July 5, 1923: 19.

42 Billy Evans, “Beat This Stunt! Finish Game with No Chance to Win,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, February 26, 1924: 9.

43 “White Sox Beat Tys in Final Game, 16-5,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1924: 19.

44 “George McBride to Help Ty Cobb,” Minneapolis Tribune, November 24, 1924: 28.

45 Detroit Free Press, January 1, 1950: 24.

46 Roger Cantwell, “Casual Remark Repeated Leads to Madison Man Who Played on Same Club with Wagner, “Wisconsin State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), December 15, 1955: 35.

47 “Roundy Says,” State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), November 14, 1968: 23.

48 “Oldest Tiger Carisch dies at 95,” State Journal (Madison, Wisconsin), April 27, 1977: 27.

Full Name

Frederick Behlmer Carisch

Born

November 14, 1881 at Fountain City, WI (USA)

Died

April 19, 1977 at San Gabriel, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.