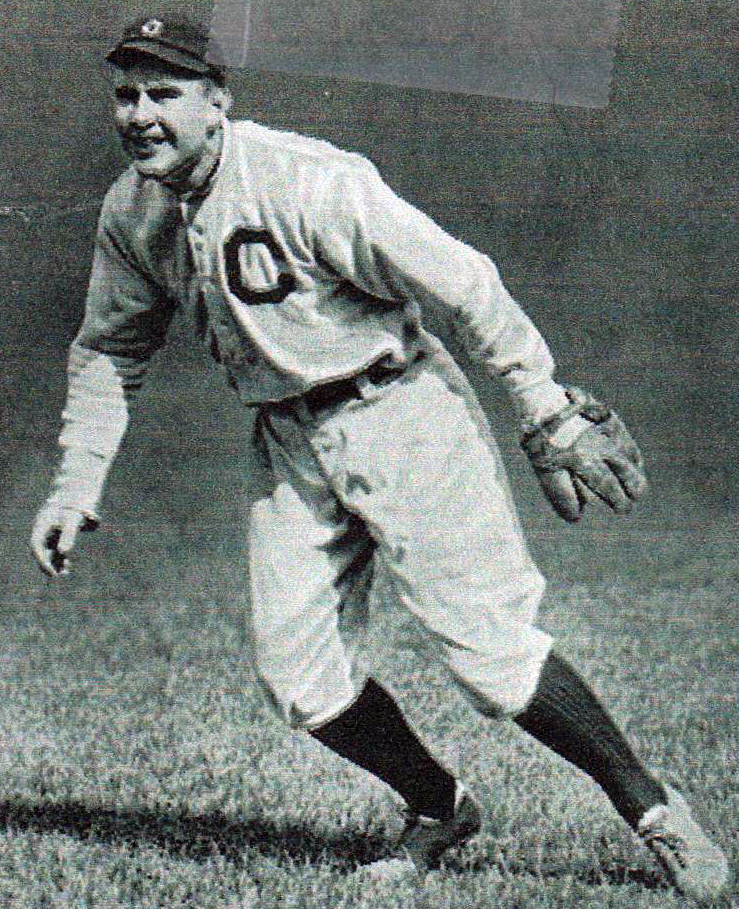

Joe Birmingham

With a lineup featuring Nap Lajoie and Shoeless Joe Jackson, the Cleveland Naps were expected to contend for the 1912 American League pennant. The club, however, proved a disappointment. By early September, a 54-71-2 (.432) record placed the Naps closer to the AL bottom than the top, and cost first-year manager Harry Davis his job. Installed in his place was 27-year-old center fielder Joe Birmingham, who immediately led the Naps to a rousing 21-7 (.750) finish. In appreciation, Cleveland club ownership extended Birmingham’s tenure, affording him a new one-year contract as Naps field leader.

With a lineup featuring Nap Lajoie and Shoeless Joe Jackson, the Cleveland Naps were expected to contend for the 1912 American League pennant. The club, however, proved a disappointment. By early September, a 54-71-2 (.432) record placed the Naps closer to the AL bottom than the top, and cost first-year manager Harry Davis his job. Installed in his place was 27-year-old center fielder Joe Birmingham, who immediately led the Naps to a rousing 21-7 (.750) finish. In appreciation, Cleveland club ownership extended Birmingham’s tenure, affording him a new one-year contract as Naps field leader.

The change in status had a dramatic effect on Birmingham’s perspective on his career. An intelligent, game-savvy young man, his forte was defense. He covered a lot of ground in center and was equipped with what was widely regarded as the best outfield arm in baseball. But he was a mediocre batsman and brittle besides, prone to leg injuries. This prompted Birmingham to see his future in managing, rather than playing. To that end, he reduced his own on-field time, first with the Naps and thereafter as player-manager for the various high minor league clubs that engaged him. The results were mixed: several commendable seasons that included an Eastern League championship commingled with lackluster showings and summary dismissals.

Thereafter, Birmingham spent his life on the periphery of the game, scouting and umpiring while holding down a government job. After an extended absence from the playing field, he had just commenced a stint as an umpire in the outlaw Mexican League when stricken with a fatal heart attack in April 1946. An account of his often hectic life follows.

Joseph Leo Birmingham was born on December 3, 1884, in Elmira, New York, a railroad hub located in the southwestern tier of the Empire State not far from the Pennsylvania border. He was the fifth of seven children1 born to saloon keeper-turned-businessman Michael Birmingham (1846-1909), an Irish Catholic immigrant, and his New York-native wife Hannah (née Connolly, 1853-1908). Joe, or “Dode” as he was known in his hometown, was educated in local public and parochial schools before matriculating to Elmira Free Academy. While there, he began to attract local press notice – as a football standout.2

Birmingham did a post-graduate year at Mercersburg Academy, a college prep school located in southern Pennsylvania, where he again garnered notice for gridiron exploits. A two-way halfback, punter, and kicker, he was the hero of Mercersburg’s upset of the University of Pennsylvania freshmen, his three long-range drop-kick field goals providing the linchpin of victory.3 As had happened at Elmira Free Academy, Birmingham’s baseball playing at Mercersburg gathered scant press notice. Rather, it was his summertime performance back home for the Father Mathew Temperance Society baseball team that drew attention. During the summers of 1904 and 1905, the right-handed batting and throwing Birmingham “won universal praise by his brilliant fielding”4 for Father Mathew, the Elmira entry in the Southern Tier League, a fast semipro/amateur circuit.

In September 1904, Birmingham entered Cornell University, intent on studying veterinary medicine and playing football for celebrated coach Glenn “Pop” Warner.5 Although only a freshman, he landed a first-string berth at halfback. His running and kicking paced the Big Red to five straights win to start the season. But just prior to the much-anticipated showdown with Princeton, Birmingham was suspended from the team on undisclosed grounds.6 He was reinstated just prior to kickoff, but to no avail. Princeton won, 18-6, despite “Birmingham [doing] well in the punting, nearly always sending the ball more than 40 yards and losing nothing in the exchanges with [the Princeton punter].”7 Shortly thereafter, he withdrew from school, his quest for a higher education at an end.8

After spending the summer of 1905 back in Elmira patrolling the Father Mathew outfield, Birmingham entered the professional ranks the following spring, signing with the Amsterdam-Gloversville-Johnstown Jags of the Class B New York State League.9 He found immediate success, hitting .303 in a league with low batting averages, with 34 extra-base hits in 117 games. That performance did not go unnoticed by major league scouts. In late August, the Jags sold his contract to the Cleveland Naps for a reported $1,500.10

Twenty-one-year-old Joe Birmingham made his major league debut on September 12, 1906, filling in at third base for injured Jap Barbeau. Although unfamiliar with the position, Birmingham handled his only fielding chance cleanly and notched two singles off left-hander Ed Siever in a tough 5-4 loss to the Detroit Tigers.11 Thereafter, he was more comfortably stationed in left field. In ten late-season games total, the newcomer batted a respectable 11-for-40 (.275) with five runs scored, six RBIs, and two stolen bases, while playing errorless outfield defense. But two career deficiencies also surfaced during his audition. In 41 plate appearances, Birmingham drew only one walk, an offensive shortcoming for a power-deficient contact hitter. And he missed the Naps’ final five games due to injury, presaging game-day unavailability that became chronic in later seasons. Still, Birmingham made a good first impression and figured solidly in Cleveland’s plans for 1907.

Apart from staying healthy, Birmingham blueprinted his major league tenure in his first full campaign. He quickly supplanted Harry Bay in the everyday lineup and proved a pillar on defense, leading American League center fielders in assists (28). Birmingham’s throws not only carried great distance in the air. They were also accurate and arrived on a line, the product of exceptional velocity.12 By midseason of his rookie year, Birmingham had acquired the nickname “Mauser Arm Dode.”13 Later, a Cleveland sportswriter maintained that “it is doubtful if any outfielder ever lived who could throw further and with the sense of accuracy as did Birmingham.”14 But his stick work – a .235/.265/.300 slash line – was substandard, and his strikeouts (73) to walks (16) ratio was worse.

Birmingham’s 1908 season was a near mirror image of the previous one. The rifle arm/weak bat combination led to a short-lived experiment that had him working out as a catcher during spring training.15 Resuming his place in the outfield once the regular season started, he again led AL center fielders in assists (20), but his hitting (.213/.253/.257) regressed, and he walked only 19 times in 451 plate appearances. He was also hobbled by foot and leg miseries, problems attributed to years of playing football.16 While Biirmingham was laid up that August, Cleveland club boss Charles Somers revived the idea of converting him into a catcher. “I believe that you will make a first-class catcher,” Somers told him. “And I will be glad if you will give your attention, when you are able to play at all, to fitting yourself to that position.”17

Birmingham was willing, but once he was fit to resume play, Naps second baseman-manager Nap Lajoie returned him to his outfield post. Cleveland finished the season a close second, only one-half game behind pennant-winning Detroit in final AL standings. Yet the personal highlight for our subject occurred off the diamond: his August marriage to Anna Kinzel of Albany. The couple’s only child, daughter Mary Madeline, would arrive in 1913.

Early in the 1909 season, Birmingham was sidelined for weeks with a right arm injury.18 When he returned, his throwing was only marginally affected while his offense improved markedly. In 100 games, his batting average (.289) and on-base average (.333) were second-best on the club, topped only by Lajoie’s .324/.378. But the 71-82-2 (.464) Naps fell to sixth place, and Lajoie’s midseason managerial resignation initiated a constant chain of successors at the club’s helm. Under coach-turned-manager Deacon McGuire, Cleveland pretty much stayed in place, with its final 71-81-9 (.467) record good for a fifth-place finish. Birmingham had a similarly mediocre season. His defense (22 center field assists) remained strong,19 but soft work with the bat (.229/.284/.270, with only 13 extra-base hits in 367 at-bats) jeopardized his spot in the lineup.

Benefiting from the lively baseball adopted for the new season, Birmingham rebounded with a career year in 1911. In 125 games, he posted career highs in base hits (136), extra-base hits (25), batting average (.304), on-base percentage (.334), slugging average (.380), RBIs (51), and total bases (170).20 Birmingham also served as unofficial lieutenant to first baseman George Stovall, installed as Cleveland manager 18 games into the 1911 season. Under its new command, the Naps surged to a third-place finish, and prospects for both Birmingham and the ballclub looked bright. In fact, it was widely reported that Birmingham would be appointed team captain for the 1912 season.21

It was not to be. During the offseason, Stovall was traded to the St. Louis Browns, and recently retired Philadelphia A’s star Harry Davis became the latest Cleveland manager. Davis, in turn, selected shortstop Ivy Olson as team captain.22 Birmingham took the rejection gracefully, stating “Harry Davis knows his business best. He knows far more baseball than I do and if it is his opinion that Olson will make a better captain you can gamble that he is right. Other things being equal, the captaincy should go to an infielder.”23 But the choice of the combative Olson proved a poor one, and Davis discharged him from duty following Olson’s altercation in late May with Naps pitcher Willie Mitchell.24 Davis then appointed Birmingham team captain. But that did not solve the first-year skipper’s problems. With key players (including Birmingham) beset by nagging injuries, erratic pitching, a discouraged locker room, and his club mired in sixth place, Davis resigned as Naps manager in early-September.

Taking the helm of a 54-71-2 (.432) club was 27-year-old team captain Birmingham. Upon assuming the post, he stated, “It’s a tough job and comes to me very suddenly. Only two weeks ago I was a bench warmer, with no expectation of becoming manager of the club. It has been my ambition, however, to become a big league manager. Whether I am ready to fill such a job now remains to be seen. I shall devote my best energies toward winning games for Cleveland and believe that the fellows will all cooperate with me. I don’t anticipate any startling changes. All we have to do is to get out and hustle. Fourth place is not impossible. We will go after it.”25

Birmingham’s appointment came with a public vote of confidence from club boss Somers. “Joe is manager. He is in full charge to sign or release [players], to run the club as he sees fit, being clothed with the authority to exert the proper discipline. I believe that he can secure just as good results as Stovall did a year ago. The players believe in him [and] he knows their faults and good qualities.” Somers also put down the rumor that Birmingham’s appointment was merely a stopgap measure until a more experienced manager could be retained. “I feel so confident that Joe will make good that I am going to dismiss the matter and not think of anyone else [for team manager],” the club boss said.

Birmingham promptly vindicated Somers’s confidence. Under their new leader, the Naps closed with a rush, going 21-7 (.750) to finish fifth. Immediately thereafter, Birmingham was reengaged for the coming season.26 His own contribution to club success had been modest (.255/.311/.331 in 107 games), and he expressed the intention to manage from the bench next year if outfield prospects made good – his own relative youth notwithstanding.27

A broken foot suffered in early 1913 going, however, mooted the issue; Birmingham spent two months on the bench recuperating, while rookie Nemo Leibold handled center field. Manager Birmingham saw action in only 47 games but was solid (.282/.324/.366) when he was in the lineup. More important, his charges responded to his stewardship. Led by the offensive production of Joe Jackson (.373) and Nap Lajoie (.335) and the hurling of Cy Falkenberg (23-10) and Vean Gregg (20-13), the Naps improved to third (86-66-3, .566) in final AL standings, and the postseason commentary on the youthful skipper was near-unanimously favorable. More tangible was the reward bestowed upon Birmingham by Somers “in appreciation for his great showing with the Naps this past season”: a brand-new seven-passenger Cadillac.28

The 1913 season proved the high point of Joe Birmingham’s career as a major league manager. The downward spiral began even before the new season commenced, when pitching staff anchor Falkenberg jumped to the newly arrived Federal League. Opening Day found Birmingham sidelined by a muscle injury and promising young shortstop Ray Chapman out indefinitely with a broken leg.29 Things did not improve as the season progressed. The nearly 40-year-old Lajoie was finally showing his age and the pitching staff faltered. Falkenberg’s replacement, Guy Morton, waited until late September to post the victory that raised his season log to 1-13.30 Birmingham, meanwhile, did the side little good as a player. He retired to the bench in late July, having appeared in only 19 games and batting a feeble (6-for-47) .128.

Beleaguered Cleveland staggered through the schedule, completing the season with a dismal 51-102 (.333) record and finishing the season in the AL basement, 48½ games behind the pennant-winning Philadelphia A’s. But club boss Somers was “tired of changing managers” and decided to stick with Birmingham in order to give him “a fair chance to show what sort of manager he is.”31 To that end, Birmingham was re-signed as Naps pilot, and given a two-year pact, to boot.32 But again, trouble surfaced during the offseason, with disgruntled starting pitcher Fred Blanding threatening to quit rather than work under manager Birmingham.33

Notwithstanding his new two-year contract – major league owners had adopted salary increases and multi-season pacts as an antidote against key personnel jumping to the Federals – manager Birmingham began the 1915 season on shaky ground. Meddlesome and impatient club owner Somers wanted a winner. On May 19, right-hander Rip Hagerman pitched the club – rechristened the Cleveland Indians34 – to a 5-2 victory over Boston to raise the club record to 12-16. That was not good enough for Somers, and Birmingham was sacked.35 In a first-person news column, he expressed surprise at his ouster. And he made the terms plain: he had been fired. “I have not resigned as manager of the Cleveland American League team. Instead of resigning, I have been told that I am no longer manager,” he wrote.36 Nevertheless, Birmingham still considered himself employed, stating, “I regard myself as a member of the Cleveland club and will continue to do so until the end of the 1916 season as my contract does not expire until then.”37

Somers publicly defended his conduct, declaring that he “knew something about baseball himself” and that Birmingham had defied his instructions to move Joe Jackson to first base and get Elmer Smith into the lineup.38 Perhaps more to the point for Somers, “Birmingham has failed to get results. I believe I gave him a fair trial and … he didn’t make good and has been dismissed.”39 In his place, veteran minor league manager Lee Fohl became the Indians’ skipper.

Although he had not made a playing appearance all season, Birmingham immediately reported for duty to Fohl. Somers responded to this awkward situation by releasing Birmingham unconditionally, but without continuing to pay his salary.40 He also barred him from entering League Park.41 But Birmingham would not go quietly. Instead, he filed a breach of contract lawsuit for payment of his 1915-1916 salary in full, plus damages.42 Birmingham then went home, his time in major league baseball at its end. In nine injury-plagued seasons as a player, he had been a mediocre hitter (.253 average), with only 129 walks in 2,876 plate appearances yielding a poor .294 on-base percentage. Nor had he hit for power: .316 slugging average, with only seven career homers. Rather, it was outfield defense that kept Birmingham in the lineup. Until baserunners learned not to challenge his arm, he led American League center fielders in assists. During his tour as Cleveland manager, he started strongly but thereafter faded to a 170-191 (.471) overall mark.

Birmingham sat out the remainder of the 1915 season. But over the winter, he and Somers settled their grievances out of court.43 That cleared the way for Birmingham to accept the post of player-manager of the Toronto Maple Leafs of the Class AA International League.44 Unhappily for him, recurring leg injuries limited him to only 37 games in the field and his relations with the Toronto fans and sports press were not cordial. Nevertheless, the Leafs (54-53, .505) were in pennant contention when Birmingham resigned in late August.45

Still only 32, Birmingham resumed his playing career with the 1917 Reading (Pennsylvania) Patriots of the New York State League, the same circuit in which he had broken into professional ball back in 1906. He was relatively healthy for a change and playing well (.302 BA in 59 games) but quit the financially troubled club rather than accept a pay cut in late July.46 With the country fully engaged in World War I and minor league baseball greatly curtailed, jobs were harder to find in 1918. But Birmingham landed a roster spot with the Toledo Iron Men of the Class AA American Association.47 He saw little, if any, game action, however, before being released in late May.48

Undaunted, Birmingham gave it another try the following spring, signing as player-manager of the Pittsfield (Massachusetts) Hillies of the Class A Eastern League.49 He hit a meager .225 in 78 games, but guided the club to a 64-44 (.593) record and the league crown. His re-signing for 1920 at an unspecified increase in salary was greeted with applause by local fans.50 But the Hillies could not repeat their success and Birmingham was discharged after the club finished sixth in the 1920 EL pennant chase.51 Weeks thereafter, he was engaged to manage the Albany Senators,52 another Eastern League club, located where he had made his offseason home ever since his marriage to a local in 1908. But his tenure proved brief. With the Senators on a 12-game losing streak that dropped their record to 6-27 (.182), Birmingham was fired.53 With that, Joe Birmingham’s time as a player or manager in Organized Baseball came to a close.

Another thing nearing its end was his marriage to Anna Kinzel. The couple divorced sometime in the early 1920s. By that time, Birmingham was scouting for the Indians.54 In 1929, he returned to the diamond as an umpire in the International League,55 but was dismissed in June.56

In late 1931, Birmingham remarried, taking Nina Loomis Danner, a 43-year-old divorcee with a teenage son, as his second wife.57 During the Great Depression, he lived in Manhattan and worked as overseer of child nutrition for the New York City Board of Education. He also scouted for the New York Giants.58 His best-known discovery was outfielder Danny Gardella,59 later a cause célèbre as a jumper to the Mexican League.

After World War II, Birmingham relocated to Hollywood, Florida. In spring 1946, he followed Gardella and others into the Mexican League, joining the outlaw circuit as an umpire. But the engagement would soon occasion his demise. On April 23, he suffered a heart attack while having dinner in a Tampico night club and died shortly thereafter in a nearby hospital.60 Joseph Leo “Dode” Birmingham was 61. Following local funeral services, his remains were returned to the United States and interred in Saquoit Valley Cemetery, Clayville, New York. Survivors included second wife Nina, daughter Madeline Kirk, and two grandchildren.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Darren Gibson and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Paul Proia,

Sources

Sources for the biographical info imparted above include the Joe Birmingham file with questionnaire maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US and New York State census data accessed via Ancestry.com; and various of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes. Unless otherwise noted, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 Joe’s siblings were John (born 1872), Thomas (1875), William (1879), Charles (called Neil, 1883), Mary Agnes (1888), and Walter (1890).

2 See e.g., “Athens Men Won from Local Team,” Elmira (New York) Gazette and Free Press, November 26, 1902: 6; “Academy Boys Beat Bingo High School,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, November 17, 1902: 3; “Elmira Academy’s First Victory,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, September 29, 1902: 3.

3 As recalled years later in “Nap Manager Shines as Great Goal Kicker,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 1, 1902: 17. For a contemporary account of the game, see “Birmingham’s Great Work,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, October 23, 1903: 3. The final score: Mercersburg 16, Penn, 6.

4 See “Elmirans Are Making Good,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, September 24, 1904.

5 “Elmirans at Cornell,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, September 14, 1904: 3.

6 See “Cornell Has Faint Hope,” Cleveland Leader, October 29, 1904: 6; “Costello and Birmingham Are Lost by Cornell,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 24, 1904: 10.

7 Per “Princeton, 18; Cornell, 6,” Baltimore Sun, October 30, 1904: 10.

8 See “Athletes,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, January 1, 1905: 6. Birmingham attempted to register for class in Spring 1905, but Cornell was not offering the law course that he wanted to enroll in at mid-year. An Elmira report that Birmingham would re-enter Cornell in Fall 1905 proved unfounded. Apart from the odd print reference, there is no historical evidence that Birmingham subsequently attended or played for Notre Dame. See also, “Birmingham’s Great Record as a Star Baseball Player,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, December 27, 1906: 3.

9 “Birmingham in State League,” Elmira Gazette and Free Press, April 5, 1906: 3.

10 As reported in “Cleveland Gets Birmingham,” Baltimore Sun, August 20, 1906: 8; “Joe Birmingham Is Sold,” Knoxville (Tennessee) Sentinel, August 20, 1906: 12; and elsewhere.

11 Per “Naps Lose Again,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 13, 1906: 8. Down 4-0 with two outs and no one on base in the ninth, the Tigers mounted a furious five-run rally for the victory.

12 See “Cleveland Owns the Greatest Outfielder in Joe Birmingham,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 25, 1909: 18.

13 Per the Trenton (New Jersey) Evening Times, July 12, 1907: 6; and Grand Rapids (Michigan) Press, July 9, 1907: 6. The Mauser was a German-built combat rifle renowned for its accuracy and killing power. The nickname was coined after a remarkable Birmingham throw from deep center nailed Browns’ base runner Bobby Wallace at the plate.

14 Henry B. Edwards, “Base Runners Fear Great Arm,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 1, 1908: 8.

15 As reported by sportswriter Milton Palmer, “Chat and Comment of Sports and Sportsmen,” Detroit Times, March 24, 1908: 3. Weeks earlier, Newark manager George Stallings had opined that with proper training, Birmingham “would make the greatest catcher baseball has ever known. … He throws just about perfect, straight from the shoulder [and] is possessed of the kind of arm that will last for years.” See “Give Birmingham to Me, I’ll Make him a Catcher,” Elmira (New York) Star-Gazette, March 7, 1908: 8.

16 See “Football Injuries Spoil Many Good Athletes,” Duluth (Minnesota) News-Tribune, April 19, 1908: 3.

17 Per “‘Dode’ Is to Catch After His Return,” Elmira Star-Gazette, August 14, 1908: 6.

18 “‘Dode’ Has Abscess on Arm,” Elmira Star-Gazette, May 22, 1909: 8.

19 In the view of the local press, “Joe Birmingham … must still be considered as having the best wing of any of the league’s outfielders.” “Strong Arms Nip Runner,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 4, 1910: 16. The opinion was widely shared, a southern newspaper observing, “Joe Birmingham … is a wonderful thrower, many competent critics saying he is the best in either of the major leagues for distance and accuracy.” See “Cubans Can Not Stand a Skinning,” Charleston (South Carolina) Evening Post, December 17, 1910: 21.

20 Paced by Shoeless Joe Jackson (.408), the Cleveland club raised its team batting average to .282, 38 points higher than the .244 mark posted the year before. The American League as a whole also benefitted from the lively baseball of 1911, as the .273 league batting average reflected a similar jump from the 1910 mark (.243).

21 See e.g., “Birmingham as Captain,” Sandusky (Ohio) Star-Journal, November 15, 1911: 9; “Joe Birmingham Will Captain Naplanders,” Washington (DC) Times, November 14, 1911: 13; “Birmingham to Be Captain of Naps Next Season,” Elmira Star-Gazette, November 14, 1911: 5.

22 Per “Davis Appoints Ivan Olson Captain, Releases Swindell, Hendryx, Barr,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 4, 1912: 12.

23 “Birmingham Is Loyal, Wishes Olson All Luck,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 5, 1912: 12.

24 See “Olson Is Deposed by Harry Davis,” Columbus (Ohio) Dispatch, May 27, 1912: 10.

25 Per “Birmingham Is Manager of Naps for Rest of Year,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 3, 1912: 7. See also, Tom Terrell, “Birmingham Succeeds Davis as Naps Manager,” Cleveland Leader, September 3, 1912: 7.

26 As reported in “Manager Birmingham,” Washington Times, October 10, 1912: 12; “Joe Birmingham Signs to Manage Cleveland,” Newark Evening Star, October 9, 1912: 14; and elsewhere.

27 See “Birmingham on Bench,” Washington Times, October 28, 1912: 11; “Wants to Manage from Bench,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, October 27, 1912: 1C.

28 As reported in the Kalamazoo (Michigan) Gazette, December 24, 1913: 7; Albuquerque (New Mexico) Journal, December 23, 1913: 3; Cleveland Plain Dealer, December 20, 1913: 9; and elsewhere.

29 As note in “Jinx Hot on the Trail of Nap Leader, Himself on Bench,” Canton (Ohio) Repository, April 25, 1914: 6; “‘Dode’ Birmingham Suffers Injury; Naps Suffer More Hard Luck,” Elmira Star-Gazette, April 16, 1914: 14.

30 Morton survived his woeful rookie campaign and went on to have a solid 11-season career as a major leaguer, all with Cleveland.

31 Per “To Retain Joe Birmingham,” Cleveland Gazette, September 15, 1914: 4.

32 See “Birmingham Will Remain Manager of Cleveland Naps,” Elmira Star-Gazette, October 21, 1914: 8. The pact included a generous raise to $6,000 for the 1915 and 1916 seasons, plus a $1,500 player option for 1917.

33 Per “Fred Blanding Good and Sore at Birmingham,” Elmira Star-Gazette, December 16, 1914: 8; “Short Lengths,” Detroit Times, December 7, 1914: 7. When Birmingham returned as Cleveland manager in 1915, the 26-year-old Blanding, an 18-game winner in 1912, made good on his threat. He never pitched another major league game.

34 The new team nickname was adopted after Nap Lajoie was sold to the Philadelphia A’s in January 1915.

35 As reported in “Birmingham Fired as Indians’ Head,” Colorado Springs (Colorado) Gazette, May 22, 1915: 7; “Joe Birmingham Fired by Somers; Lee Fohl in Charge,” Detroit Times, May 21, 1915: 1; “Birmingham Deposed as Cleveland Leader,” Grand Rapids Press, May 21, 1915: 20; and elsewhere nationwide.

36 Joe Birmingham, “‘I Did Not Resign’ Says Ex-Manager Birmingham,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 22, 1915: 11.

37 Same as above.

38 Per the Washington (DC) Herald, May 24, 1915: 9.

39 Same as above.

40 The Birmingham contract did not contain the standard 10-day clause, thus enabling his immediate release.

41 See “Somers Bars Former Manager from Park,” Philadelphia Inquirer, June 23, 1915: 13.

42 As reported in “Birmingham Will Sue Cleveland Ball Club,” Grand Rapids Press, June 23, 1915: 16; “Birmy to Fight,” Trenton Evening Times, June 20, 1915: 27; and elsewhere. The litigation also sought repayment of the $10,000 that Birmingham had loaned the cash-strapped Somers in late 1914.

43 The settlement terms were not publicly disclosed, but it was generally believed that Somers paid Birmingham his 1915 salary in full and was released from his contract obligation to pay for 1916. See Henry P. Edwards, “Birmingham Withdraws Suit Against Old Club,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 26, 1916: 9.

44 See “Will Boss Toronto Leafs This Season,” Calgary (Alberta) Herald, February 23, 1916: 8; “Joe Birmingham to Manage Torontos,” Ottawa (Ontario) Citizen, February 19, 1916: 8.

45 As reported in “Birmingham Resigns,” Columbus Dispatch, August 23, 1916: 15; “Joe Birmingham Resigns as Manager of Leafs – Claims Injury as Cause,” Pawtucket (Rhode Island) Times, August 23, 1916: 6; and elsewhere.

46 See “Baseball Notes,” (Portland) Oregon Journal, August 13, 1917: 8; “Three Quit Reading,” Harrisburg (Pennsylvania) Telegraph, July 30, 1917: 9.

47 See “Birmingham Signs with Toledo,” Philadelphia Inquirer, April 8, 1918: 14; “With Toledo,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard, April 7, 1918: 6.

48 Per “Birmingham Has Failed with Bush League Club,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, May 31, 1918: 20. American Association stats for all players appearing in at least ten games during the 1918 season are provided in the 1919 Spalding Official Baseball Guide. The name Joe Birmingham is not listed therein.

49 A reported in “Birmingham Signs,” Cincinnati Post, May 28, 1919: 14.

50 See “Joe Birmingham Signs Contract,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, November 16, 1919: 16; “Joe Birmingham Gets Another Term” Springfield (Massachusetts) News, November 8, 1919: 14

51 “Birmingham Out as Manager of Pittsfield,” Connecticut Labor Press, November 6, 1920: 7; “Birmingham Released by Pittsfield Baseball Club,” Worcester Evening Gazette, October 29, 1920: 20.

52 See “Birmingham as Albany Manager,” Springfield Republican, December 22, 1920: 5; “Joe Birmingham to Manage Albany,” Albany Times-Union, December 21, 1920: 13.

53 Per “Passing of Birmingham,” Bridgeport (Connecticut) Evening Farmer, June 2, 1921: 9; “Paddy O’Connor to Manage Albany,” Springfield Republican, June 2, 1921: 5.

54 See “Joe Birmingham Is Now a Cleveland Scout,” Bridgeport Evening Farmer, May 24, 1922: 17. See also, Salt Lake Telegram, February 24, 1924: 10.

55 Per “Carpenter Names Umpires for Coming Season,” Watertown (New York) Times, March 26, 1929: 10; “International League Has Staff of Ten Umpires,” (Jersey City) Jersey Journal, March 25, 1929: 14.

56 According to “Changes Umps,” Syracuse Herald, June 13, 1929: 20.

57 The 1930 US Census designated Birmingham as a lodger in the Manhattan residence of Mrs. Danner and her son. The couple married shortly after Nina’s divorce was finalized in September 1931.

58 As reported in the Jersey Journal, October 1, 1937: 16.

59 See the Elmira Star-Gazette, June 5, 1944: 9.

60 Per “Birmingham, Ex-Indian Pilot, Dies in Mexico,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 26, 1946: 20. See also, American Foreign Service Report of the Death of an American Citizen, June 7, 1946, contained in the Joe Birmingham file at the Giamatti Research Center.

Full Name

Joseph Leo Birmingham

Born

December 3, 1884 at Elmira, NY (USA)

Died

April 24, 1946 at Tampico, Tamaulipas (Mexico)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.