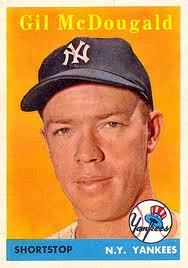

Gil McDougald

New York Yankees infielder Gil McDougald led a life of accomplishment both on and off the diamond. During his ten seasons in pinstripes, McDougald was the 1951 American League Rookie of the Year, a five-time All-Star team selection, and a member of eight American League pennant winners. Although often overshadowed by Cooperstown-bound teammates like Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford, McDougald was the glue that held together the Bombers’ infield of the 1950s, handling fielding duties expertly whether stationed at second, shortstop, or third base. He was also a capable batsman, particularly in clutch situations and at World Series time.

New York Yankees infielder Gil McDougald led a life of accomplishment both on and off the diamond. During his ten seasons in pinstripes, McDougald was the 1951 American League Rookie of the Year, a five-time All-Star team selection, and a member of eight American League pennant winners. Although often overshadowed by Cooperstown-bound teammates like Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford, McDougald was the glue that held together the Bombers’ infield of the 1950s, handling fielding duties expertly whether stationed at second, shortstop, or third base. He was also a capable batsman, particularly in clutch situations and at World Series time.

Quiet and self-effacing but fiercely competitive, McDougald was admired by teammates, opposing players, the baseball press, and fans alike. Away from the field, McDougald was a man of sterling character, a religiously devout father of seven who regularly engaged in civic and charitable work, focusing particularly on helping underprivileged children and supporting the athletic activities of the Catholic Youth Organization (CYO).

Sadly, a long life of sporting achievement and community service was scarred by McDougald’s connection to a baseball tragedy: a scorching line drive through the box that felled young Cleveland flamethrower Herb Score on May 7, 1957. From that day until his obituaries were composed some 53 years later, Gil McDougald’s name was invariably linked to that at-bat and the ensuing death spiral of a pitching career of brilliant promise.

Gilbert James McDougald was born in San Francisco on May 19, 1928, the younger of two sons born to William James McDougald (1895-1978), a genial cigar-store owner turned laundry-company salesman, and his wife, the former Ella McGuire (1896-1973).1 At San Francisco’s Commerce High School, a skinny Gil McDougald (6-feet-1 but then far thinner than his eventual 180-pound playing weight in the major leagues) was an All-City basketball player. But he did not make the varsity baseball team until his senior year. And then, injuries limited his playing appearances to five games.2

Following graduation in 1946, Gil took classes at City College of San Francisco and the University of San Francisco, while playing semipro baseball with a local Boston Braves feeder team called the Bayside Braves. In order to hit the curveball better, right-handed batter McDougald adopted a weird-looking but effective batting stance, with legs splayed open to the pitcher and the bat cocked at waist level. Most major-league scouts lost interest in McDougald as soon as they got a look at him at the plate, but Gil impressed Yankees West Coast scout Joe Devine. “You knew you were looking at a great one the moment you saw him,” Devine said later. “He has great instincts, he learns fast and he’s a spirited player.”3

With Braves scout Bill Lawrence supplying the only competition, Devine signed Gil to a $200-per-month Yankees contract with a $1,000 bonus in the spring of 1948.4 Though he was still short of 20 years old, there was much pressure on McDougald to make good, as he had just assumed familial obligations. On April 8, 1948, Gil had married San Franciscan Lucille Tochilin, the daughter of Russian immigrants, and by 1952 the newlyweds would be parents to four children, Christine, Gilbert Jr., Tod, and Denise.

McDougald skyrocketed through the Yankee farm system. Playing for the Twin Falls Cowboys of the Class C Pioneer League, he batted .340 and was selected as the league All-Star at second base in 1948. Promoted the following year to the Victoria Athletics of the Class B Western International League, he turned in a near mirror-image performance, batting .344 (with 64 extra-base hits) and was again chosen the league’s All-Star second baseman. Jumped up to the Double-A level with the Texas League’s Beaumont Roughnecks for the 1950 season, McDougald was the beneficiary of tutelage by manager Rogers Hornsby, a Hall of Fame second baseman and the game’s greatest right-handed batter. A curmudgeon who often disdained young players, Hornsby took an immediate liking to 22-year-old McDougald, his unconventional batting stance notwithstanding, and lavished attention upon him. McDougald responded with another superb season, batting .336 with a league-leading 187 hits while providing the pennant-winning Roughnecks with excellent defensive play. He was chosen the Southern Division second baseman for the midseason Texas League All-Star game and voted the league MVP by local sportswriters at year’s end.

With their two-time World Series champion lineup returning virtually intact for the 1951 season, the Yankees appeared to have little need for infield replacements. But the outbreak of hostilities in Korea had injected uncertainty into the situation. All-Star second baseman Jerry Coleman, a US Marine Reserve aviator, and third baseman Bobby Brown were both liable to be called to military service at any time, while infield prospect Billy Martin had already been drafted into the Army. Meanwhile, veteran third sacker Billy Johnson was aging (33) and a contract holdout. To bolster manpower, at least for spring-training purposes, club brass directed McDougald, previously ticketed for their Triple-A farm team in Kansas City, to report to the Yankees camp in Phoenix.5 Once he heard the news, mentor Hornsby privately assured Gil that he was capable of big-league play. “Fight hard,” Rajah counseled. “You are ready. You are going to get the break of your life. Make the most of it.”6 Thereafter, Hornsby informed the sporting press that the green McDougald was already “a major league caliber” ballplayer.”7

Once Gil had arrived in camp, Yankees manager Casey Stengel also took a quick shine to him, particularly after the Old Perfessor decided that the young prospect could handle third base as well as second. Nor was Stengel alarmed by McDougald’s unorthodox batting stance. “Maybe McDougald does hold the bat cockeyed,” observed Casey. “But there ain’t anything wrong with the way he swings it.”8 For the next six weeks McDougald received extended playing time, particularly at third base, and performed well. When the club headed north, Gil McDougald, still a month shy of his 23rd birthday, was officially a member of the New York Yankees.

With Jerry Coleman and Billy Johnson in Yankees uniforms and off to fast starts, McDougald saw little action in the early going. On April 20, 1951, he made his major-league debut as a late-inning replacement at second base in a 5-3 loss to Chicago. For the next week, McDougald remained on the bench, his place on the roster seemingly threatened by the arrival of Bobby Brown, released from his medical internship at a West Coast hospital, on April 24, and Billy Martin, discharged from military service on hardship grounds, the following day. But the prophecy that McDougald would soon be demoted to Kansas City9 did not take into account the fact that manager Stengel was smitten with the young infielder and determined to give him a chance. Inserted into the starting lineup at third base on April 27, McDougald responded with his first big-league hit, a single off Boston ace Mel Parnell, and flawless play in the field. In the games that followed, McDougald remained in the lineup, cementing his place in Yankee plans with an offensive eruption on May 3. In a game in St. Louis, Gil tied a then-American League record by driving in six runs in a single inning, two on a triple off left-hander Irv Medlinger, and the remainder via a grand slam served up by Bobby Herrera. Two days later McDougald blasted another homer against the Browns. By May 10 the Yanks (15-6) were back in their customary roost atop the AL standings, with McDougald having assumed a regular place in Stengel’s infield rotation. Gil platooned with lefty batter Brown at third, and replaced the oft-injured Coleman at second base against right-handed pitching.10 As the season wore on, Gil sustained his outstanding level of play, and by year’s end, he had appeared in 131 games. With a .306 batting average, McDougald led a Yankees club that had Joe DiMaggio, Mickey Mantle, and Yogi Berra, and he placed among the American League top ten in batting, on-base percentage (.396), slugging (.488), OPS (.884), and stolen bases (14).

The 1951 Yankees followed their third consecutive AL pennant with a third consecutive World Series victory, besting the New York Giants in six games. As in the regular season, McDougald was a major contributor to the Yanks’ good Series fortune. He hit a grand slam off the Giants’ Larry Jansen in Game Five and was the Series’ top RBI man (7). Weeks later, baseball writers capped McDougald’s Cinderella season by naming him the American League Rookie of the Year.11 The Yankees also rewarded Gil, near doubling his salary for the 1952 campaign to $12,000.12 With his immediate future seemingly secure, McDougald relocated the family to New Jersey, the state where he would reside for the remainder of his life.

McDougald turned in a solid, if unspectacular, year as a Yankee sophomore. Appearing in 152 games (mostly at third base), Gil batted .263, with 11 home runs and 78 RBIs, as New York edged the Cleveland Indians for their fourth consecutive AL pennant. He was named to the 1952 American League All-Star squad as a reserve, and grounded out in his lone plate appearance. He supplied more firepower during the World Series, homering in Game One, as the Yanks bested the Brooklyn Dodgers in seven games for another World Series crown. The 1953 season was much the same for both McDougald and New York. His batting average rebounded to .285, with a career-best 83 RBIs. The Yankees, meanwhile, coasted to a fifth consecutive pennant, and then defeated Brooklyn again in a six-game World Series that included home runs by McDougald in Games Four and Five.

To accommodate the inclusion of Andy Carey in the lineup, Gil reverted to his natural position at second base for most of the 1954 season. The new arrangement clicked for New York. Carey batted .302 and the Yanks logged a sparkling 103-51 (.669) record, their best during Stengel’s 12-year tenure as manager. But with Cleveland posting a phenomenal 111-win season, that was not near good enough for another pennant. During the ensuing offseason, the still youthful McDougald began to plan for a future after baseball. With a friend named Ernie Lantz, he founded a northern New Jersey janitorial service named (with permission of New York club owners Dan Topping and Del Webb) Yankees Building Maintenance Company. The enterprise would flourish and provide the McDougald family a reliable income for the next 30 years.

Things reverted to normal in 1955, with the Yankees returning to the top of the AL heap. As usual, McDougald chipped in his share for the New Yorkers, batting a solid .285 and playing a standout second base. But the season was not without incident for McDougald. During batting practice before a mid-August game, he was struck in the head by a Bob Cerv line drive. He was diagnosed with a mild concussion, and he returned to diamond action within days. Undetected was a small skull fracture and damage to the left inner ear. Over time, McDougald would suffer a diminution of hearing in that ear, but it would not affect his playing career. Years later, however, the Cerv beaning would produce profound consequences.

Meanwhile, for the first and only time, postseason destiny would favor the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1955. McDougald had a minor role in newsreels memorializing the Dodgers thrilling 2-0 victory in Game Seven. Gil was the runner doubled off first after Sandy Amoros’s celebrated catch in the sixth inning. That fall the Yankees undertook a good-will exhibition tour in Japan. By that time it was clear that longtime star Phil Rizzuto (who did not make the Far East trip) was on his last legs as the Yankees shortstop. During the season, the intermittent substitution of slick-fielding but punchless Billy Hunter into the lineup had been no more than a stopgap measure, and prospects like bonus baby Tommy Carroll and farmhands Woodie Held, Jerry Lumpe, Bobby Richardson, and Tony Kubek were deemed unready to assume the position for the 1956 campaign. Accounts differ regarding what precipitated the tryout of McDougald, but he appeared at ease when dispatched to short during the Japan tour. McDougald’s fielding style was much like his batting stance. It appeared graceless to the eye, but was highly effective. Gil possessed defensive intelligence, sure hands, good range, and an accurate throwing arm. And despite being established as a second baseman, he was willing to take on a new position. “I’m not exactly in love with shortstop,” McDougald said during spring training. “But I will play anywhere as long as I get to play. Personally, I’d prefer to play second base. That’s where I really feel at home. But I think that I can get to like playing shortstop, if I play there long enough.”13

Reportedly signed for $25,000 for 1956,14 McDougald turned in an outstanding season, batting a career-high .311, and was selected to his second AL All-Star team. Paced by the Triple Crown performance of Mickey Mantle (.353/52/130), the Yankees breezed to yet another AL pennant, and that October, World Series fortunes reversed, with New York beating Brooklyn in seven games. In the memorable Game Five, shortstop McDougald provided one of the fielding gems that preserved Don Larsen’s perfect game, snaring a hot shot deflected by Andy Carey deep in the hole and throwing out Jackie Robinson. In recognition of his contribution to Yankee success, Gil finished seventh in MVP balloting, while the Better Sports Club of Arlington, Virginia, honored him as Baseball Sportsman of the Year for his off-the-field work with civic and charitable organizations.15

As the 1957 season began, 28-year-old Gil McDougald appeared destined for still greater baseball achievement. But the batting style that had served him in such good stead was about to render a life-altering experience. Although he hit the occasional long ball (10-14 home runs per season), McDougald was more a slashing line-drive hitter who used the entire field. His drives up the middle put pitchers, little more than 50-plus feet away at the end of a delivery, at particular risk. On May 1 a McDougald liner back through the box struck Detroit right-hander Frank Lary in the hip, necessitating his removal from the game. Six days later, the Yankees squared off against 23-year-old Herb Score. The hard-throwing lefty, the 1955 AL Rookie of the Year, a 20-game winner in 1956, and the major-league strikeout leader both seasons, was already the American League’s most dominant pitcher and, barring misfortune, seemed headed for Cooperstown. The second batter Score faced that evening was McDougald. With the count standing at 2-and-2, McDougald turned a Score fastball into a blistering drive back through the box. Score had no chance to react. The ball struck him directly in the right eye, and then caromed to third baseman Al Smith, who made the play to first. By then McDougald was no longer running, having veered off the basepath to join those gathered around Score, crumpled on the mound, his glove covering a bloodied face. Removed to a Cleveland hospital, Score had numerous facial bone fractures, and the sight of his right eye was in jeopardy. Back in the Yankees’ dressing room, McDougald was disconsolate, vowing to quit the game if Score lost the eye. Later unable to sleep, McDougald, road roommate Hank Bauer, and Yogi Berra attempted to visit Score at the hospital, but were informed that the patient was not allowed visitors. News of McDougald’s distress subsequently reached Score’s mother in Florida, who telephoned Gil to assure him that the Score family bore him no ill will, and wanted him to stay in the game.16 Herb himself sent McDougald a similar message, describing the incident as “just part of the game,” and telling others, “It wasn’t his fault. I don’t hold any grudge or ill-feeling at all.”17

Despite Score’s magnanimity, the incident left a lasting scar on the McDougald psyche. When informed some years later that a struggling Score had been sent back to the minors, Gil was heartsick. “I guess I didn’t pray hard enough,” said McDougald, who shared Score’s devout Catholicism. “I feel that I jeopardized a good living for him. He had a lot of years ahead of him, good years. If there was anything I could do, I’d do it. But there’s nothing. All I can do is pray.”18 But the wreckage of the Score career would take several seasons to unfold, and in 1957, McDougald, like the rest of the baseball world, was hopeful that Score would soon be his former self on the mound. In the meantime, Gil consoled himself with another fine campaign. He batted .289, with a career-high 87 runs scored and belted an AL-leading nine triples. He was also stalwart in the field, being a top-three shortstop in double plays turned, putouts, and assists — despite ceding significant late-season playing time to heir apparent Tony Kubek. The 1957 American League pennant race was another laugher for the Yanks, but New York was an upset loser to the Milwaukee Braves in a seven-game World Series. A year later, the clubs switched positions, with the Yankees rallying from a three-to-one deficit to take the seven-game 1958 World Series. Home runs by McDougald in Games Five and Six keyed the New York comeback.

During the postseason, McDougald was among the athletes feted by the Sports Lodge of the B’nai Brith, and voted “most popular Yankee” by the CYO of the Archdiocese of New York. He was also the recipient of the Lou Gehrig Award, the first Yankees player ever to receive the prestigious honor. Such encomiums met with the approval of New York sports beat writer John Drebinger, who had previously written, “Any award for McDougald meets with tremendous popular approval, for the Yankees seldom have had a player more liked or, for that matter, more valuable.”19 But testimonials did not delude McDougald. Although still relatively young, he realized that his playing performance had entered its decline. He had followed a substandard 1958 regular season (.250 BA) with another one like it in 1959 (.251), and had lost middle-infield playing time to Kubek and Bobby Richardson. Gil was now back at third base, where he would have to fight off the challenge of a slick-fielding Yankee newcomer, Clete Boyer. Sensing the inevitable and loath to uproot his family, McDougald privately advised Yankees brass that 1960 might be his final season.

McDougald made modest contributions to the Mantle-Maris powerhouse that dominated the 1960 American League, splitting time at third with Boyer and periodically spelling Richardson at second. He saw more action in the ensuing World Series against the underdog Pittsburgh Pirates, appearing in every game but one. McDougald entered the epic Game Seven as a ninth-inning pinch-runner and then took a defensive station at third. He was not there long. Within minutes, Bill Mazeroski’s famous drive over the left-field wall brought the Series — and the major-league playing career of Gil McDougald — to an end.

Over his ten-year Yankees career, McDougald had compiled more than respectable stats: a .276 batting average, with 112 homers and 576 RBIs. More important had been his defensive versatility — he was an All-Star team member at three different positions. In the estimation of Bill James, McDougald was one of the three players “who made Casey Stengel a genius.”20 Gil had played with Yankee legends who regularly overshadowed his performance: DiMaggio, Mantle, Berra, Rizzuto, Whitey Ford, et al. But he had been a vital member of eight pennant winners, and his value was not lost on those charged with building a major-league baseball team from scratch.

Expansion would be coming to the American League in 1961, with new franchises in Washington and Los Angeles to be stocked from the roster of existing American League teams. Although the Yankees were coy about their intentions, McDougald realized that he would be exposed to the expansion draft. Having already decided privately to retire and not wishing to see the new clubs squander a draft pick on him, McDougald made his intentions public. Unhappy New York general manager Roy Hamey stated that McDougald would not be replaced on the list of Yankee expendables, for fear of setting “a bad precedent, giving other veteran players the idea that they could threaten to quit rather than be sent to one of the fledgling franchises.”21 Most others shared the view expressed by New York Times columnist Arthur Daley who, citing the “extra touch of class, honesty, decency and integrity” that McDougald had brought to the club, concluded that Gil had “announced his retirement when he did because it was the honorable thing to do.”22

McDougald was a man of his word. Not even Gene Autry’s offer of a two-year, $50,000-a-season contract with free housing could coax Gil into an Angels uniform.23 But McDougald was not abandoning the game altogether. Instead, he accepted general manager George Weiss’s offer to serve as a talent scout for the fledgling New York Mets organization.24 Within months, however, being again on the road proved disagreeable to McDougald, and he resigned his scouting position. This permitted Gil to concentrate his attentions on his janitorial service, family, community service, and playing golf. In 1965 the McDougald family expanded via the adoption of daughter Courtney Ann. “I love children, and if it were up to my wife, I think that she’d like to run an orphanage,” McDougald later explained.25 The McDougalds had taken in foster children during Gil’s playing days but had been turned down for adoption because they already had four children of their own. By the time those children had grown up and left the house, the impediment to adoption became the McDougalds’ age. But “less desirable” nonwhite children were available, so Gil and Lucy later adopted two biracial infants, sons John and Michael. “You don’t see color or religion when you adopt. … Who cares? We just wanted kids,” said Gil.26

In the 1960s McDougald continued his civic and charitable work, which often involved him in youth sports. In August 1969 he stepped up his sports commitment, accepting the position of baseball coach at Fordham University in the Bronx. Although hampered by a cold climate, a limited game schedule, and a limit of three scholarships a year, Gil did a fine job, posting two 20-win seasons and being named the 1975 Fordham athletics department coach of the year. Unfortunately, the hearing loss that had gradually stemmed from the 1955 batting practice line drive was now pronounced. Frustrated by his inability to communicate with his players more effectively, McDougald resigned after the 1976 season. As his hearing continued to deteriorate, he avoided the old-timer’s games that had kept him in touch with Yankees teammates, and gave up other social activities. Because he found it impossible to use the telephone, McDougald sold off his business interests. He even withdrew from the dinner table, despondent about his inability to follow family conversations. By the late 1980s, McDougald was almost totally deaf.

In July 1994 McDougald’s misery was chronicled by sports reporter Ira Berkow in the New York Times.27 The Berkow article, captioned “McDougald, Once a Quiet Yankee Star, Living in a Quiet World,” proved a life-changer. Medical experts reading the article thought McDougald a likely candidate for a cochlear implant, and put him in touch with Dr. Noel Cohen, chief of otolaryngology at New York University Medical Center. Following surgery performed in November 1994, McDougald and family had to wait an agonizing six weeks before the operability of the implant could be tested. Tears of joy were shed when Gil was able to hear again, and for the remainder of his life Gil McDougald would be a crusader for the treatment, particularly in children.28

In November 2008 McDougald was saddened by the death of Herb Score. But by then Gil himself was seriously ill with prostate cancer. He died at home in Wall Township, New Jersey, on November 28, 2010. He was 82, and was survived by wife Lucy, seven children, 14 grandchildren, and seven great-grandchildren. Following private funeral services, Gil McDougald was interred at St. Catherine Cemetery in nearby Sea Girt. He had led a long and useful life — a fine ballplayer and an even better man.

Notes

1 Sources for the biographical detail provided in this profile include the Gil McDougald file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York, and certain of the newspaper articles cited below. William James McDougald was born in Stockton, California, of Scotch-Irish descent, his own father having emigrated from Canada. By the time his son Gil reached the Yankees, Bill McDougald was a dispatcher with the San Francisco Post Office. Like her husband, Ella McGuire McDougald was California-born. Gil’s older brother, William Joseph McDougald (1927-2006), spent his entire working life in the employ of General Mills, primarily stationed in Minnesota, where he raised a large family of his own and coached a girls’ softball team for 20 years.

2 The Sporting News, May 16, 1951.

3 Ibid. See also, Greensboro Record, July 27, 1951.

4 The signing placed McDougald in the company of accomplished San Francisco-area infielders who had also become Yankees, including Tony Lazzeri, Frank Crosetti, Jerry Coleman, and, later, Andy Carey.

5 Although young and physically fit, McDougald, married and already the father of three young children, had been classified 3-A by his draft board and stood virtually no chance of being inducted into the military.

6 As recalled by McDougald in The Sporting News, May 16, 1951.

7 Dallas Morning News, March 21, 1951.

8 New York Times, February 27, 1951.

9 See e.g., The Sporting News, May 2, 1951.

10 The Yankees’ infield logjam was relieved by the May 14 trade of Billy Johnson to the St. Louis Browns, and by the placement of Billy Martin on the National Defense List. Martin remained with the Yankees during the 1951 season but saw only sparing action.

11 McDougald prevailed over Minnie Miñoso of the White Sox in a close 13-11 BBWAA vote.

12 New York Times, January 24, 1952. McDougald had started the 1951 season at the $5,000 MLB minimum, but his outstanding play had induced the Yankees to accord him a late-season salary “adjustment.”

13 Trenton Evening Times, March 18, 1956.

14 New York Times, February 19, 1956.

15 Washington Post-Times Herald, November 19, 1956.

16 As reported in the New Orleans Times-Picayune and The Sporting News, May 15, 1957, and elsewhere.

17 As reported in the Chicago Tribune, May 9, 1957, and elsewhere. Score remained hospitalized for three weeks, and spent the remainder of the 1957 season on the Cleveland disabled list. He recovered his vision and exhibited flashes of his former brilliance early the next season. But Score snapped a tendon in his pitching arm during an April 1958 game against Washington, and was never the same after that, spending the next six years in a futile search for his past form before retiring from the game at age 30. For a comprehensive account of Score’s life, see his BioProject profile by Joseph Wancho.

18 Los Angeles Times, May 10, 1962.

19 New York Times, August 18, 1957.

20 Bill James, The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract (New York: The Free Press, 2001), 505. The other two were Mickey Mantle and Yogi Berra.

21 Chicago Tribune, December 10, 1960. Sometime after his separation from the Yankees, McDougald renamed his janitorial services business Metropolitan Maintenance.

22 Arthur Daley, “Positions Unchanged,” New York Times, December 16, 1960.

23 San Francisco Examiner, March 11, 1961. McDougald’s top salary with the Yankees had been approximately $35,000.

24 New York Times, May 4, 1961.

25 Boston Herald, December 29, 1978.

26 Ibid.

27 New York Times, July 10, 1994.

28 See Ira Berkow, “Baseball: The Sweetest Sound of All: McDougald, Yankees Star Can Hear Again After Operation,” New York Times, January 4, 1995, and Jim Riesler, “Sounds Great to Him: Former Yankees Star Gil McDougald Regained His Hearing After Cochlear Implant,” Sports Illustrated, September 16, 1996.

Full Name

Gilbert James McDougald

Born

May 19, 1928 at San Francisco, CA (USA)

Died

November 28, 2010 at Wall Township, NJ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.