Hideo Nomo

Like Babe Ruth, he was a savior for the major leagues when the game was at risk of losing fans. Like Jackie Robinson, he was a courageous pioneer who blazed a trail and opened new doors of opportunity for others to follow. Like Fernando Valenzuela, he was the pride of a specific ethnic community, yet adored by people of all races and creeds. Like Bob Gibson, he was a fierce competitor on the mound, and a friend to all who knew him off the field. Like Luis Tiant, his twisted and contorted windup fooled hitters on every team, and delighted fans in every ballpark. Like Nolan Ryan, his dedication to conditioning and training was legendary, and unmatched by his peers. Like Sandy Koufax, he was a fireball who appeared suddenly and blinded the competition, then faded away. Like Ted Williams, Ernie Banks, Tony Gwynn, and countless other greats, he was blessed by the baseball gods with the passion and skills to play the game at a higher level, but was denied the glory of ever winning a World Series. And finally, like Buck O’Neil, his career statistics on the field will (most likely) prevent him from being enshrined in Cooperstown, despite the fact that he is arguably one of the game’s most important ambassadors. When you stop and realize that all of these qualities are embodied in a single ballplayer, you begin to fully appreciate his career, his legacy, and the undeniable truth that there is no one else in the history of game quite like Hideo Nomo.

Like Babe Ruth, he was a savior for the major leagues when the game was at risk of losing fans. Like Jackie Robinson, he was a courageous pioneer who blazed a trail and opened new doors of opportunity for others to follow. Like Fernando Valenzuela, he was the pride of a specific ethnic community, yet adored by people of all races and creeds. Like Bob Gibson, he was a fierce competitor on the mound, and a friend to all who knew him off the field. Like Luis Tiant, his twisted and contorted windup fooled hitters on every team, and delighted fans in every ballpark. Like Nolan Ryan, his dedication to conditioning and training was legendary, and unmatched by his peers. Like Sandy Koufax, he was a fireball who appeared suddenly and blinded the competition, then faded away. Like Ted Williams, Ernie Banks, Tony Gwynn, and countless other greats, he was blessed by the baseball gods with the passion and skills to play the game at a higher level, but was denied the glory of ever winning a World Series. And finally, like Buck O’Neil, his career statistics on the field will (most likely) prevent him from being enshrined in Cooperstown, despite the fact that he is arguably one of the game’s most important ambassadors. When you stop and realize that all of these qualities are embodied in a single ballplayer, you begin to fully appreciate his career, his legacy, and the undeniable truth that there is no one else in the history of game quite like Hideo Nomo.

Nomo was born on August 31, 1968, into a working-class family in the industrial section of Osaka, Japan. His father, Shizuo, and mother, Kayoko, had great hopes for their son, naming him Hideo (pronounced He-day-oh), which translates literally to “excelling man,” but is commonly understood to mean “superman” or “hero” in Japanese.1

He started playing baseball with his father at age 5 and by the time he was 12 his dream was to become a professional ballplayer. In the fifth grade he invented his corkscrew “tornado” windup to impress his father, and to fool batters. “By twisting my body and by using this force, I was able to throw harder. And at the same time, with that motion, it would be difficult for batters to pick up the ball,” he explained.2

When Hideo reached middle-school ball he dominated batters with his speed, and frightened them with his lack of control. At times he would walk the bases loaded only to strike out the side. The head coach of Kindai High School, the top school-baseball program in Osaka, told Nomo, “Young man, with that tornado windup, you’ll never make it.”3 Nomo used the criticism as inspiration when he enrolled in the lesser-known Seiyo Industrial High School. There he dominated the local competition, and even pitched a perfect game.

Despite his 6-foot-2, 200-pound frame, when he graduated from high school in 1987 Nomo failed to catch the attention of college and pro scouts. Instead, he joined the Shin-Nitestsu Sakai, a company-sponsored club in the semipro industrial leagues, where he perfected both his corkscrew motion and his forkball. He was so dedicated to mastering the forkball grip that at night before going to sleep he taped a tennis ball between his index and middle fingers.4

Nomo earned a spot on Team Japan, which won a silver medal in the 1988 Olympics in Seoul, South Korea. The next year he received offers from a record eight teams in the 1989 Nippon Professional Baseball draft. Nomo signed with the Osaka-based Kintetsu Buffaloes and received a bonus of 100 million yen (roughly $1 million US) and a guarantee that the team would not try to change his pitching form.5

Buffaloes manger Akira Ogi was an easygoing character who endeared himself to Nomo. As a result, Nomo gave Ogi-san everything he had on the mound. Armed with a blazing fastball and a wicked forkball, Nomo tied for the league lead in wins (18-8) and led with a 2.91 ERA and 287 strikeouts in 235 innings. He won the Rookie of the Year award, the Most Valuable Player award, and the Sawamura Award, given to the best pitcher in NPB. For the next three seasons he led the Pacific League in wins and strikeouts. And because of his unorthodox windup, he also earned the nickname “Tatsu-maki” – Japanese for “The Tornado.”6

The young Nomo also bonded with teammate Masato Yoshii, a veteran pitcher three years his senior. Masato took Hideo under his wing when he first turned pro, and in addition to teaching Nomo the ins and outs of professional baseball, he also shared with him his dream of one day playing in the US major leagues. “Masato was a diehard major-league baseball fan for a long time,” said translator Kota Ishijima, who worked with both Nomo and Yoshii with the Mets. “Their relationship was quite strong. With regard to Hideo’s interest in playing in the major leagues, Yoshii strongly influenced him.”7

After the 1990 season, the Japanese all-stars battled the visiting major-league all-stars, winning four games in the best-of-seven series. Nomo’s performance caught the eye of several Americans, including Ken Griffey Jr. and Randy Johnson. The Big Unit approached Nomo at a private dinner in Japan and told him, “You belong in MLB.”8 With Johnson’s praise, and the strong influence of Kintetsu teammate Masato Yoshii, Nomo could not shake the thought of going to America to compete in the majors.

In 1994 manager Ogi was replaced by Keishi Suzuki, a Japanese Hall of Fame pitcher with an impressive résumé: 317-238 record, fourth all-time in wins; 3,061 strikeouts, and 340 games pitched without a walk, an NPB record. Suzuki followed a militaristic training regimen and believed that the remedy for a sore arm was to throw more. “Throw until you die,” he said.9 By the time Nomo left the NPB, he had thrown more than 140 pitches in a single game 61 times. The excessive pitch counts took their toll on the righty. He was injured most of the 1994 season and finished with an 8-7 record, appearing in only 114 innings, down 53 percent from 243 1/3 the previous season.10

After the 1994 season Nomo met baseball agent Don Nomura, who had translated the Japanese Uniform Players Contract searching for loopholes to recruit players to the United States. With the help of California-based agent Arn Tellem, they found one – the voluntary-retirement clause. It stated that if a player retired and returned to NPB, he was bound to his former team. However, there was no provision for players who retired and went to another country to play. This was Nomo’s out. After the ’94 season, he declared his retirement from NPB at age 26.

After interviewing with several major-league teams, including the Los Angeles Dodgers, San Francisco Giants, and Seattle Mariners, Nomo found a personal connection with Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley and signed with the team in February 1995.

That spring the relationship between the major leagues and its fans was at an all-time low. The previous season was killed by the players strike, a conflict that many perceived as an unrelatable argument over money between billionaires (the owners) and millionaires (the players). The 1994 World Series was canceled. Fans were disgusted and some vowed never to step foot in a major-league ballpark again. Many fans had a change of heart after Nomo arrived in America.

Nomo signed a minor-league contract with the Dodgers’ Double-A team, the San Antonio Missions, who had just hired new pitching coach Luis Tiant, a fellow tornado-style pitcher. Nomo reported to spring camp in Vero Beach, Florida at the end of February and immediately impressed Tiant. “He’s a smart pitcher. … (If) you’re good, you’re good, no matter where you pitch,” Tiant said in his endearing Cuban accent.11

By the end of April the Dodgers were convinced Nomo was ready for the big leagues, but wanted the rookie to get a tune-up start with one of their minor-league clubs.12 In his American professional baseball debut, Nomo pitched 5 1/3 innings for the Bakersfield Blaze of the California League against the Rancho Cucamonga Quakes. With little run support, the Blaze lost 2-1, but the Dodgers were pleased with Nomo’s performance and called him up. They announced that he would make his first start on May 2 against the San Francisco Giants in Candlestick Park.13

By the end of April the Dodgers were convinced Nomo was ready for the big leagues, but wanted the rookie to get a tune-up start with one of their minor-league clubs.12 In his American professional baseball debut, Nomo pitched 5 1/3 innings for the Bakersfield Blaze of the California League against the Rancho Cucamonga Quakes. With little run support, the Blaze lost 2-1, but the Dodgers were pleased with Nomo’s performance and called him up. They announced that he would make his first start on May 2 against the San Francisco Giants in Candlestick Park.13

With his start against the Giants, Nomo became the first Japanese-born player to join a major-league team after officially retiring from the NPB. When he joined the Dodgers, only one other Japanese native, Masanori Murakami, had played in the major leagues. Murakami returned to Japan after playing with the Giants in 1964-65.14

His predecessor offered Nomo a congratulatory message in the press: “I wish him all the best and hope he has great success as a Japanese major-leaguer. I would like to see him do well against everybody – except for the San Francisco Giants.”15

Murakami’s jest helped fuel Nomo when he pitched against San Francisco. By the end of his career, he had compiled a 13-7 record against the Giants, 4-5 when pitching in Los Angeles and 9-2 in San Francisco, an .818 winning percentage in the Bay City. Throughout his career Nomo was “a Giant killer” in their own ballparks, Candlestick/3Com Park and PacBell/AT&T Park. (Nomo’s personal best in any opposing city was .833 at Tropicana Field in St. Petersburg.)

In his major-league debut, Nomo pitched five scoreless innings, allowing one hit. He left the 0-0 game after the fifth inning and did not get a decision. (The Dodgers lost to the Giants 4-3 in 15 innings.) Among the 200 members of the media present, most were from Japan. Only 16,099 fans paid to see the game at Candlestick Park (just 28 percent of the 58,000 capacity). However, millions in Japan watched the game live on television, where the first pitch was thrown at 5:33 A.M.

After six starts, Nomo ended May with five no-decisions and one loss. June would be a different story. He recorded his first major-league win against the New York Mets on June 2, a 2-1 victory. In eight innings he allowed just two hits, a home run and single, both to Bobby Bonilla. Nomo went undefeated for the entire month of June, going into the midseason break with a 6-1 record, a 1.99 ERA, and 119 strikeouts in 90 1/3 innings pitched.

Nomo had one of the greatest Junes in Dodgers history. In each of his six starts, he pitched at least eight innings. He gave up just five earned runs in 50 1/3 innings, allowing 25 hits and 16 walks while striking out 60. In winning six straight games, he capped the month with back-to-back complete-game, 13-strikeout shutouts. No other Dodgers pitcher had ever thrown back-to-back shutouts with 13 or more strikeouts.16

Shortly before the 1995 All-Star Game, Atlanta Braves pitcher Greg Maddux suffered a groin injury running to first base.17 Maddux’s injury made Nomo the potential starter for the National League. The Braves ace said, “I think more people want to watch him pitch than me, to be honest.” Nomo got the official nod to start from NL manager Felipe Alou.

The game was played on July 11 in Texas at The Ballpark in Arlington in front of 50,920 fans. Fittingly, Nomo’s boyhood idol, Nolan Ryan, threw out the ceremonial first pitch. Nomo pitched two innings and faced six batters. He struck out three (Kenny Lofton, Edgar Martinez, and Albert Belle), allowed one hit (a single by Carlos Baerga, who was caught stealing) and no walks. The NL won the game, 3-2, on a home run by Jeff Conine in the eighth.18 Nomo had a great outing, but would never pitch in another All-Star Game.

Nomo’s spotlight in the All-Star Game also helped heal a nation and improve relations between the United States and Japan. His brilliance in the 1995 season was a source of great pride and a much-needed morale boost for the Japanese.19 The country had recently experienced acts of terrorism, a massive earthquake, economic recession, and rising unemployment. Nomo’s performance was welcome relief for his country.20

In the late 1980s to early 1990s US-Japan relations were poor due to American perceptions of unfair trade practices in Japan. Some American politicians engaged in “Japan bashing” through policy and public-relations stunts like destroying Japanese-made products with sledgehammers on the evening news.21 Critics observed that there was a lot of “unwarranted, irrational, racially tinged hostility toward the Japanese.”22 Attitudes in the United States toward Japan started to change when Nomo arrived.

“Nomo’s impact will be so great as to recast the image of the Japanese people in the American imagination,” wrote the Mainichi News.23 Historians compared Nomo to Babe Ruth, who visited Japan in 1934. The US ambassador said then that Ruth was so popular in Japan that “one Babe is better than a hundred ambassadors.” For the same reason, one Japanese scholar observed, in 1995, “Nomo is better than 100 Japanese ambassadors to Washington.”24

At the end of the season Nomo was named NL Rookie of Year after notching a 13-6 record and a 2.54 ERA, and leading the league with 236 strikeouts in 191 1/3 innings. “I think I had a great year with the Dodgers, and I’m satisfied,” he said.25 “My next goal is to pitch for the Dodgers in the World Series.”26

Nomo’s Rookie of the Year Award was a disappointment for Braves rookie Chipper Jones, who had his sights set on winning the award when he was drafted years earlier. A key contributor to the Braves’ 1995 postseason success, Jones said, “He’s got something I don’t have, but I’ve got something he doesn’t have – a World Series ring.”27

In 1996 Nomo went 16-11, pitched his major-league career high of 228 1/3 innings, and reduced his walks to a career-low 3.4 per nine innings pitched. His performance helped the Dodgers finish with a 90-72 record, one game behind the Western Division-leading San Diego Padres. Los Angeles secured the wild-card spot in the postseason, but was swept by the Braves in the Division Series. (Nomo started the third and final game of the series and gave up five runs in 3 2/3 innings.)

While a World Series championship eluded Nomo in 1996, the Japanese righty found himself once again making history on the mound. On April 13 he struck out a career-high 17 batters in a 3-1 victory over the Florida Marlins.28 On September 17 he pitched a no-hitter against the Colorado Rockies at hitter-friendly Coors Field.

Nomo was 3-0 against Colorado in his career, but the mile-high altitude had never been kind to him. He had never won a game in the Rockies’ home ballpark.29 Furthermore, Colorado was an offensive powerhouse in 1996. By the end of the season the Rockies led the NL in home runs (221) and stolen bases (201). Their lineup included three 40-home-run hitters, Andrés Galarraga (47), Ellis Burks (40), and Vinny Castilla (40). Dante Bichette and Eric Young were also among the top offensive performers in the National League.

Nomo dominated the Rockies hitters in the game and won 9-0. In the improbable no-hitter, he struck out eight and walked four. Dodgers manager Bill Russell was stunned by Nomo’s achievement. He said, “That was huge, especially to do it in Colorado. With the hitters they have over there and for Nomo to throw a no-hitter … is a tremendous effort.” 30

“(Nomo) probably doesn’t realize how unbelievable that accomplishment is,” said teammate Eric Karros. “People in Japan probably don’t know Coors Field, but I’m betting it won’t be done again.”31

Karros was correct in his prediction. As of the 2016 season, no other pitcher had thrown a no-hitter in Coors Field. More than 20 years later, some argue that Nomo’s feat, particularly against one of the best-hitting teams of all time – was “the greatest regular-season pitching performance in baseball history.”32

In 1997 Nomo set a major-league record for starting pitchers by reaching 500 strikeouts in 444 2/3 innings. That was one-third of an inning less than Dwight Gooden‘s record of 445 innings set in 1985.33 Nomo’s record was later broken by Kerry Wood (404 2/3), Yu Darvish (401 2/3), and the late Jose Fernandez of the Marlins, who surpassed them all in 2016 by reaching the milestone in 400 innings.34

On paper Nomo’s 1997 season looked somewhat average, and even uneventful. Unbeknownst to him and those around him though, his career began its downward spiral that season. The critical moment occurred on July 26 when the Phillies’ Scott Rolen knocked Nomo out of a game with a line drive off his pitching arm. Rolen’s shot was the only hit Nomo allowed in 3 2/3 innings. The Dodgers won the game, 4-1, but the smash changed everything for Nomo.

He quickly returned to pitching, but by the end of the season his elbow required surgery to remove bone chips and calcium deposits. In hindsight, the career-altering impact of Rolen’s line drive off Nomo suggests parallels to the beanball that leveled Boston Red Sox slugger Tony Conigliaro in 1967. Both athletes eventually returned to the field and displayed flashes of their former brilliance, but neither was ever truly the same player again.

Rolen was the batter Nomo hit most often during his career. Nomo hit the Phillies shortstop three times, all after the line-drive incident. According to Nomo each hit-by-pitch was an honest mistake. “Absolutely not intentional,” he declared. “He’s a great hitter. I was just trying to jam him inside. I will not give him any more sweet pitches.”35

The 1998 season marked the beginning of the end of “Nomomania” in Los Angeles. With a 2-7 record and 5.05 ERA, the 29-year-old right-hander was removed from the Dodgers’ 40-man roster after complaining when he learned that his name had been included in trade talks with Seattle for Randy Johnson.36 Both the Yankees and Mets expressed an interest in Nomo, but the Mets appealed to him most because of familiar faces in the clubhouse. Among them were rookie pitcher Masato Yoshii, one of Nomo’s best friends from Japan; his former Dodgers catcher, Mike Piazza; and Dave Wallace, his former Dodgers pitching coach, now a senior adviser for New York.37 On June 4 the Dodgers traded Nomo with Brad Clontz to the Mets for Greg McMichael and Dave Mlicki.

Getting Nomo’s career back on track was the Mets’ top priority. Even his new teammates tried to help. Mets outfielder Butch Huskey thought he had the solution. He said the right-hander was tipping his pitches. “You could figure out what pitch he was throwing,” Huskey said: When Nomo was throwing a fastball, his left pinkie was visible at the height of his windup. When he threw a splitter, his pinkie was in his glove. Huskey said that ex-Mets Tim Bogar and Bill Spiers discovered the flaw during Nomo’s rookie season. Mets pitching coach Bob Apodaca alerted Nomo. “He’s a professional. I don’t want him to be overly concerned,” Apodaca said. “It might just be a matter of putting his hand up higher in his glove. Or getting a bigger glove.”38

The change of scenery or glove size didn’t help Nomo in New York. He pitched only slightly better for the Mets the second half of 1998. After spring training in 1999, the Mets released him, choosing to give the aging Orel Hershiser a try instead.39

Nomo signed a minor-league contract with the Chicago Cubs, who gave him an extended spring training and required him to start three games with the Triple-A Iowa Cubs. After assessing his performance, the Cubs would either put him on the major-league roster or release him. Rick Kranitz, the Cubs’ roving pitching instructor, declared, “I don’t see why he can’t pitch in the big leagues. The ball’s jumping out of his hand.”40 But Nomo was released after his final start.

Nomo next signed with the Milwaukee Brewers. He pitched one solid outing for the Double-A Huntsville Stars and the Brewers brought him up. In Milwaukee, Nomo returned to his lucky jersey number 11 that he once wore with the Kintetsu Buffaloes in Japan. Nomo had a good season, going 12-8. Nomo got his groove back, thanks in part to a close relationship with manager Phil Garner.41 “He seems to do well for people he likes,” Garner observed.42

On September 8, 1999, Nomo became the third-fastest starting pitcher to reach 1,000 strikeouts, trailing only Roger Clemens and Dwight Gooden.

Unable to come to an agreement on a long-term contract with Milwaukee, Nomo entered the 2000 season as a free agent. He signed a one-year contract with the Detroit Tigers for $1.25 million and the chance to earn an addition $3.25 million in performance bonuses. In Detroit he reunited with Phil Garner, now the Tigers manager.

With the Tigers Nomo had to abandon his lucky jersey number 11, which had been worn by former manager Sparky Anderson and would be retired when Anderson was elected to the Hall of Fame. So Nomo settled for 23, previously worn by Kirk Gibson. When asked what he knew of Gibson, Nomo said, “He played well for the Dodgers and the Tigers.” Nomo hoped to do the same.

In the season opener in Oakland, Nomo pitched a three-hitter and struck out eight in seven innings. The Tigers won, 7-4, and the season started on a promising note for Nomo and his new team. By the end of the season Nomo led the Tigers pitching staff with 181 strikeouts in 190 innings pitched, but also held the dubious distinction of leading the team in home runs allowed. He gave up a career-high 31 homers, six of them to the Boston Red Sox. His season was also marred by nagging injuries. In August he experienced discomfort in his throwing hand, radiating pain that originated in the first knuckle of his middle finger and shot down both sides of the finger. The Tigers training staff suspected that the injury was the result of Nomo’s spreading his fingers to throw his forkball.

Despite the injuries, home runs allowed, and losses (he was 8-12), Nomo enjoyed his time as a Tiger. One night in Milwaukee after pitching six innings, he wore an eight-foot-tall costume of an Italian sausage and secretly participated in – and won – County Stadium‘s nightly Sausage Race.43

Nomo’s enjoyable season came to a sour end when the Tigers released him. The Red Sox came calling and signed him to a one-year, $3.25 million contract with a signing bonus of $1.25 million.44 Unlike the Tigers, the Red Sox were impressed that Nomo was sixth among AL starters with 181 strikeouts and third in strikeouts per nine innings (8.57). Nomo also had 17 quality starts (six innings or more and three earned runs or less allowed). They believed there was still some gas in Nomo’s tank and that his arm could help the team. “I’m happy to be part of the Red Sox team,” Nomo said. “I’m going with the Red Sox because they have a strong chance to go to the World Series.” As he did in Milwaukee, Nomo donned his lucky jersey number 11 in Boston.

In his first start with the Red Sox, on April 4, 2001, Nomo pitched the second no-hitter of his career, defeating the Baltimore Orioles, 3-0, in Camden Yards. He joined Cy Young, Jim Bunning, and Nolan Ryan as the only major-league pitchers to throw a no-hitter in both the American and National Leagues. (Randy Johnson joined the group with his perfect game in 2004.)

Nomo struck out 11 and walked three. The no-hitter was the first thrown at Camden Yards. It also was the first of four no-hitters caught by Boston’s Jason Varitek in his career. And it was the earliest calendar date on which a no-hitter had been pitched. (Bob Feller threw a no-hitter on Opening Day in 1940, but that occurred on April 16.)45 The old Nomo was back, and it wasn’t just for one game. He went on to finish the 2001 season with a 13-10 record and lead the American League in strikeouts with 220.

The major-league game with the largest viewing audience in Japan had been Nomo’s debut game. On May 2 Nomo pitched in the game with the second largest audience. The Red Sox played the Seattle Mariners in Seattle and Ichiro Suzuki was in his first season with the Mariners.46 The game started at noon in Japan and was an instant classic.47 The Mariners won, 5-1. Nomo held Suzuki hitless but drilled him in the middle of the back with a fastball. The blow left the Mariners’ leadoff hitter gasping for breath. “It was a fastball that I wanted to throw inside,” Nomo said. “The cutter stuck on my fingers longer than I wanted, so the ball was more inside than I wanted.” Ichiro joked about the incident later, saying, “I never imagined that my first hit-by-pitch would be done by a Japanese pitcher in Major League Baseball.” 48

After rejuvenating his career in Boston, Nomo turned down the Red Sox’s offer of $19 million for three years and re-signed with the Dodgers. He earned close to $22 million over the next three seasons in Los Angeles. But by turning down the Red Sox offer he missed an opportunity to achieve the one goal that eluded him during his major-league career. Had he stayed in Boston, he might have been a member of the historic 2004 Red Sox team that “Reversed the Curse” and won the organization’s first World Series in 86 years.49

When Nomo returned to Los Angeles in 2002 he quickly learned that this was not the same Dodgers organization he once knew. The O’Malley family had sold the team to Rupert Murdoch, the owner of News Corporation, the giant media conglomerate.

In Nomo’s first season back, the Dodgers finished 92-70. They held first place for 30 games throughout the season, but finished in third place in a strong NL West behind the wild-card San Francisco Giants, who advanced to the World Series against the Anaheim Angels. Nomo finished the season with 193 strikeouts in 220 1/3 innings and a 16-6 record, the best winning percentage (.727) of his major-league career. He was 9-5 at the All-Star break and got on a hot streak, winning 11 of 12 games in the second half.

In 2003 the Dodgers improved to second place despite a worse record (85-77) than the season before. Nomo started a team-high 33 games and compiled a 16-13 record with 177 strikeouts in 218 1/3 innings. He pitched two shutouts and two two-hitters. His 3.09 ERA was the sixth best in the NL and the second best of his career. The Dodgers pitching staff had three players from Japan: Nomo, Masao Kida, and Kaz Ishii.

Nomo missed two weeks in September with shoulder inflammation and had surgery in the offseason to “clean up” the rotator cuff. Afterward, the velocity on his fastball dropped dramatically, from the 90-mph range down to the low to mid-80s. “I can’t get strength behind my pitches,” Nomo complained. The Dodgers noticed the decline in velocity at the beginning of spring training but hoped he would come around.

Manager Jim Tracy proclaimed Nomo the staff ace after the departure of Kevin Brown.50 But the ace never appeared. In July the Dodgers placed Nomo on the 15-day disabled list with rotator-cuff inflammation.51

After achieving the best winning percentage of his career the previous season, Nomo struggled in 2004. He finished with a 4-11 record (a .267 winning percentage, a career low) and an 8.25 ERA, the highest ERA ever for a pitcher with at least 15 decisions. The Dodgers sent Nomo to Triple-A Las Vegas for a brief stint and eventually released him at the end of the season.

Nomo signed a minor-league contract with Tampa Bay for 2005. With the Devil Rays he returned to his lucky uniform number. One reporter commented that Nomo wore number 11 “any season when he feels he has something to prove.”52 At the start of the season, Nomo had 196 career wins between Japan and the major leagues, and desperately wanted win number 200. “In Japan, 200 wins is a big deal,” a Japanese sportswriter said. “It will ensure Nomo’s spot in the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, if he hasn’t earned one already.”53

After the rotator-cuff injury and the attempt to repair it, Nomo was clearly no longer the pitcher he used to be. “It’s his guts, his competitiveness that makes him an effective pitcher,” said Tampa Bay general manager Chuck LaMar.54 On June 15 Nomo allowed two runs in seven innings as the Devil Rays defeated the Milwaukee Brewers, 5-3. It was career win 200, qualifying him for the Japanese Golden Players Club, known in Japan as the Meikyukai.55 Membership in the Meikyukai is automatic for position players with 2,000 hits and pitchers with 200 victories. Nomo’s win made him the 45th member of the Golden Players Club and the 16th pitcher.56

“He’s had a great career and this is a special win,” said Tampa Bay manager Lou Piniella. “We didn’t have champagne, but we had the beer, so he got doused with beer and everybody gave him a standing ovation, which was really respectful of a heck of a competitor and a great pitcher.”57 But by midseason Nomo was sitting on an unimpressive 5-8 record and a 7.24 ERA, and with a stockpile of young arms in the Tampa Bay farm system, the team released him.

The 36-year-old veteran was immediately picked up by the New York Yankees but pitched only at Triple-A Columbus. After the season his contract with the Yankees was not renewed.

In March 2006 Nomo signed with the Chicago White Sox, the defending World Series champions. He started one game for Triple-A Charlotte and afterward was put on the disabled list with a sore elbow. He was released in June. Nomo resurfaced 16 months later and about 20 pounds heavier, signing with the Leones del Caracas in the Venezuelan League. The 39-year-old pitcher arrived in Venezuela in October 2007 because of his friendship with Leones manager Carlos Hernández, Nomo’s batterymate during his first two seasons in the major leagues. When asked if this was a first step to returning to the majors, Nomo answered, “I’m taking things slow, this is a first step, if all goes well, I’ll think about looking for the opportunity to return.”

In January 2008 Nomo agreed to a minor-league contract with the Kansas City Royals. Despite his history of shoulder problems, the Royals were intrigued with Nomo as a middle reliever and as a mentor for rookie pitcher Yasuhiko Yabuta. “Hideo has a lot of experience and can help guide him along and serve as a role model,” said Royals GM Dayton Moore.

Nomo pitched three games in relief in April as a member of the Royals. Against the heart of the Yankees lineup, he surrendered home runs to Alex Rodríguez and Jorge Posada in the ninth inning. Undeterred, the veteran struck out fellow countryman Hideki Matsui to end the inning. Against the Mariners, Nomo faced Ichiro Suzuki, who struck out swinging on a 2-and-2 pitch.

In his third and final appearance for the Royals, on April 18, Nomo relieved Yabuta in the bottom of the eighth inning against Oakland. He faced four Oakland hitters and allowed a single, double, and a home run – a triple shy of the cycle, and a heartbreaker for anyone rooting for a Nomo career comeback. Travis Buck went down swinging to end the inning. It was the final strikeout of Nomo’s 12-year major-league career. The Royals released him a week later.

In July 2008 Nomo announced his retirement from professional baseball at age 39.58 Slugger Hideki Matsui said, “He was a pioneer for all of us. He helped all of us come to the major leagues. All of the players who have come from Japan owe him a debt of gratitude.”59

“Before Hideo came over here everyone had an image of major-league baseball and people looked at players over here as monsters because they were so big,” said Ichiro Suzuki. “We were able to watch more MLB games and were able to get an image of, ‘Maybe I can play in the big leagues.’”60

After retirement Nomo joined the Orix Buffaloes, the current incarnation of his former Japanese team. He traveled occasionally with the team during the 2009 season and worked with the pitchers.61 In 2010 he became a part-time adviser for the Hiroshima Carp, and also invested in a team in Japan’s Industrial League.62

Nomo had participated in instructional camps in the past, but in retirement he found a new passion in coaching and helping to develop young players. He founded the Nomo Project, an initiative designed to help introduce young Japanese players to the experience of playing baseball in America.63

In 2011 Nomo partnered with Shigetoshi Hasegawa to create the USA-Japan Youth Baseball Games, a tournament for players 15 and younger. Nomo’s Junior All-Japan team joined with Hasegawa’s Southern California-based ROX Baseball Club, the Japan-based International Baseball Exchange Committee team and the Urban Youth Academy team to make up the participants in the tournament. 64

In 2014, his first year of eligibility for election to the Hall of Fame, Nomo received only six votes (1.1 percent) and was thus removed from the Cooperstown ballot. The voting on the other side of the Pacific was a different story. For the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, he received 82.4 percent of the 324 votes, well above the 75 percent needed for induction.65

Nomo joined the elite group with Victor Starffin (1960) and Sadaharu Oh (1994) as the only people elected to Japan’s Baseball Hall of Fame in their first year of eligibility. He also became the youngest person ever to be inducted, at the age of 45 years and 4 months. When Nomo learned that he had been elected to the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame, he was doing what he loved most: He was on the field helping to develop future All-Star players with his own boys baseball tournament.

Nomo’s son, Takahiro, joined the family business of baseball after graduating from Menlo College in California in 2015. He was named the team translator for the Nippon Ham Fighters, winners of the 2016 Japan Series (Japan’s equivalent of the World Series).66 In 2016 Nomo and former Dodgers executive Acey Kohrogi joined the San Diego Padres to help increase the team’s presence in the Pacific Rim.

In reflecting on Nomo’s legacy, Dave Wallace, former Dodgers pitching coach, said, “He was the first one. He had everything to lose and nothing to gain. He set the table for a lot of other guys, who are now reaping the benefits. Japanese players will always owe him for that.”67

Since Nomo’s arrival in 1995, a total of 58 other Japanese-born players have pursued their major-league dreams in America.

“For him to come over and leave a successful career behind in Japan the way he did … he had to have some guts to do that,” said former Dodgers teammate Eric Karros. “And then to succeed the way he did with the media watching him 24 hours a day? There may be better players from Japan who come to MLB, but Nomo will always be the man,” he said. “There’s Nomo up here, then there’s the rest.”68

Last revised: February 9, 2017

Photo credits

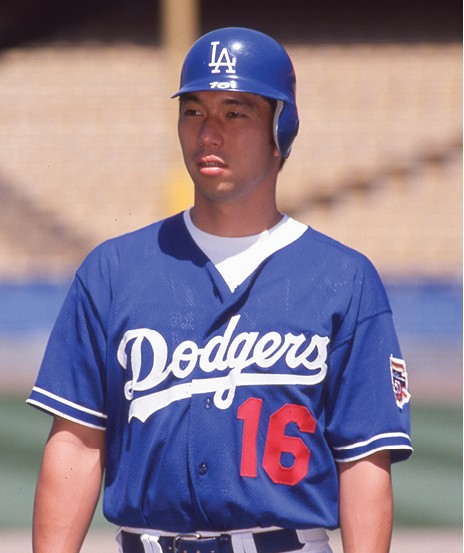

Hideo Nomo portrait: Courtesy of Jerry Coli / Dreamstime.

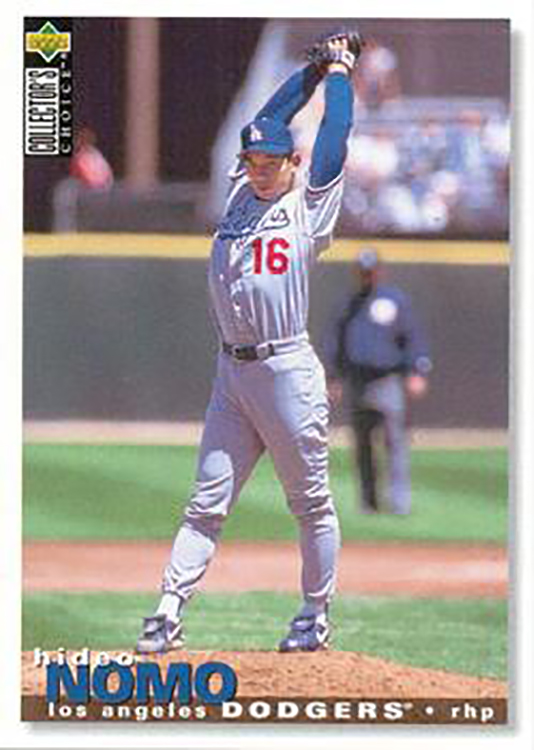

Hideo Nomo baseball card: Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Jrank.org, “Net. Hideo Nomo – Super Tornado,” sports.jrank.org/pages/3447/Nomo-Hideo-Super-Tornado.html#ixzz4UAhMsTQV, accessed November 20, 2016.

2 Robert Whiting, The Samurai Way of Baseball: The Impact of Ichiro and the New Wave from Japan (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2005), 98.

3 Alan M. Klein, Growing the Game: The Globalization of Major League Baseball (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2006), 71.

4 Whiting, 99.

5 Whiting, 99.

6 Jrank.org, “Net. Hideo Nomo – Super Tornado.”

7 Kota Ishijima, Nomo’s former translator, email interview, January 13, 2017.

8 Whiting, 97.

9 Whiting, 101.

10 Ken Daley, “Dodgers Forgo MRI Exam for Pitcher Nomo,” Los Angeles Daily News, February 14, 1995.

11 Ken Daley, “Spark(y) Is Lacking in Game – Anderson, Lasorda Differ on Dispute,” Los Angeles Daily News, March 4, 1995.

12 Cindy Martinez Rhodes, “Spirit Not Snubbed by Nomo’s Start for Blaze,” Riverside (California) Press-Enterprise, April 26, 1995.

13 Eric Noland, “Dodgers Notes – Nomo Not Nervous About Making Debut at Candlestick,” Los Angeles Daily News, May 1, 1995.

14 Noland.

15 Ken Daley, “Japanese Import Delivers – Dodgers’ Nomo Fulfills Dream in Pitching Debut,” Los Angeles Daily News, May 3, 1995.

16 Craig Minami, “Dodger Rookie Hideo Nomo Starts 1995 All-Star Game,” True Blue LA, July 12, 2013.

17 “Injured Maddux Decides to Skip All-Star Appearance – Braves Ace Strained his Groin Thursday Night Against Dodgers,” Kansas City Star, July 8, 1995.

18 Craig Minami, “Dodger Rookie Hideo Nomo Starts 1995 All-Star Game.”

19 Cameron W. Barr, “A Welcome Ray of Sunlight for Gloomy Japan,” Christian Science Monitor, July 5, 1995.

20 Barr.

21 Martin Tolchin, “The Nation: Japan-Bashing, Becomes a Trade Bill Issue,” New York Times, February 28, 1988.

22 Tolchin.

23 Barr.

24 Barr.

25 Chuck Johnson, “Top Rookie Nomo ‘Really Appreciates’ New Teammates,” USA Today, November 10, 1995.

26 Dave Allen, “L.A.’s Nomo Is Rookie of the Year,” Deseret News (Salt Lake City), November 10, 1995.

27 Johnson.

28 Gordon Edes, “Nomo Baffles Marlins, Strikes Out 17,” South Florida Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), April 14, 1996.

29 Video: MLB Classics, “9/17/96: Nomo’s No-No,” youtube.com/watch?v=Bv2_wo2l72A,, accessed November 27, 2016.

30 “Dodgers’ Nomo Pulled No-Hitter Right Out of Thin Air at Coors Field,” Spokesman.com, September 19, 1996.

31 “Dodgers’ Nomo Pulled No-Hitter Right Out of Thin Air at Coors Field,” Spokesman.com, September 19, 1996.

32 “Dodgers’ Nomo Pulled No-Hitter Right Out of Thin Air at Coors Field,” Spokesman.com, September 19, 1996.

33 “Nomo Returns to the Dodgers,” Deseret News, (Salt Lake City), December 21, 2001.

34 Zachary D. Rymer, “Fastest Starter to 500, How Far Can Jose Fernandez Climb MLB’s All-Time K List?” Bleacher-Report.com, July 18, 2016.

35 Don Bostrom, “Swollen Elbow Causes Rolen to Miss First Game,” Allentown (Pennsylvania) Morning Call, August 26, 1997.

36 Jack Curry, “Nomo Released by Dodgers, May Land With Mets,” Fort Worth Star-Telegram, June 2, 1998.

37 Curry.

38 Thomas Hill, “Mets Finger Pinkie as Nomo’s Weak Spot,” New York Daily News, June 8, 1998.

39 T.J. Quinn, “Official Sayonara for Nomo – Yoshii May Be History Soon,” The Record (Hackensack, New Jersey), March 27, 1999.

40 Dave Van Dycke, “Nomo Still Presenting A Puzzle – Theories Abound, But Cubs Taking A Look,” Chicago Sun-Times, April 18, 1999.

41 Tom Haudricourt, “They Go Hand in Glove – Nomo’s Comfort Zone With Garner Leads Him to Detroit,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, February 28, 2000.

42 Haudricourt.

43 “Names in the Game,” Associated Press Archive, July 9, 2000.

44 Sean McAdam, “Red Sox Acquire Hideo Nomo,” Providence Journal, December 15, 2000.

45 Murray Chass, “Baseball: Nomo Hurls a No-Hitter in His Red Sox Debut,” New York Times, April 5, 2001.

46 Jeff Horrigan, “Baseball – Sox Slip Up in Seattle – Ichiro, Mariners Sail to 5-1 Victory,” Boston Herald, May 3, 2001.

47 Horrigan.

48 Horrigan.

49 MLB.com, “Red Sox Break the Curse,” m.mlb.com/video/v19983103/ws2004-gm4-red-sox-complete-a-fourgame-series-sweep, accessed October 29, 2016.

50 Bill Plunkett, “Dodgers’ Winning Streak Ends at Six,” Orange County Register (Santa Ana, California), May 13, 2004.

51 Rich Hammond, “Dodgers Notebook: Injured or Not, Nomo on DL,” Los Angeles Daily News, July 2, 2004.

52 Roger Mooney, “Japan’s Wonder: Rays’ Nomo Left Everything to Play Ball in America,” Bradenton (Florida) Herald, April 15, 2005.

53 Mooney.

54 Mooney.

55 Carter Gaddis, “Rays’ Nomo Finally Nails Down Victory No. 200,” Tampa Tribune, June 16, 2005.

56 Gaddis.

57 Gaddis.

58 “Around the Bases,” Miami Herald, July 18, 2008.

59 Mooney.

60 Mooney.

61 NPBtracker.com, “Nomo Travels with Orix,” npbtracker.com/2009/04/nomo-travels-with-orix/, April 15, 2009.

62 Robert Whiting, “Nomo’s Legacy Should Land Him in Hall of Fame,” Japan Times, October 24, 2010.

63 Ben Platt, “Japanese Youth Get Taste of American Baseball,” MLB.com, August 24, 2011.

64 Platt.

65 Kaz Nagatsuka, “Nomo Inducted Into Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame,” Japan Times, January 17, 2014.

66 Kei Nakamura, “Sports Graphic Number Web (Japanese),” January 30, 2015, number.bunshun.jp/articles/-/822582, accessed December 30, 2016.

67 Robert Whiting, “Nomo’s Legacy Should Land Him in Hall of Fame.”

68 Robert Whiting, “Nomo’s Legacy Should Land Him in Hall of Fame.”

Full Name

Hideo Nomo

Born

August 31, 1968 at Osaka, Osaka (Japan)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.