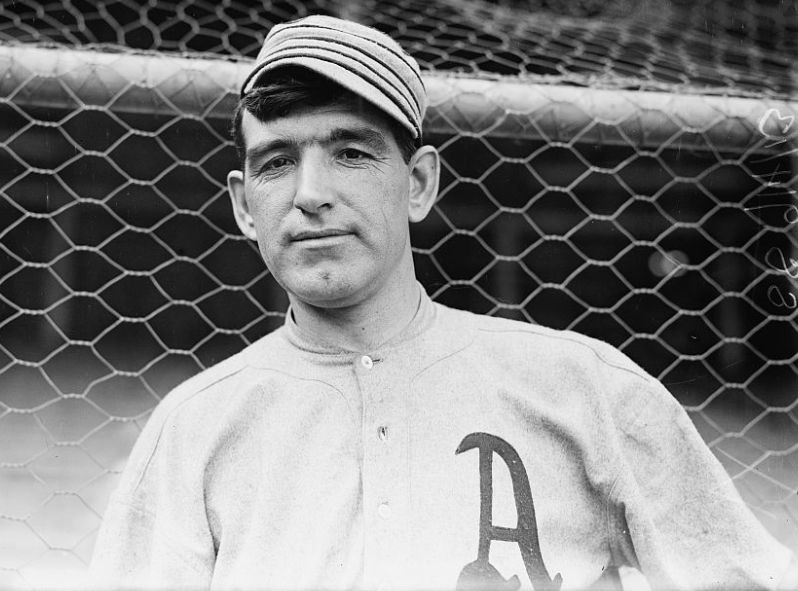

Ira Thomas

A weak-armed washout from two other American League teams, catcher Ira Thomas was purchased by Connie Mack prior to the 1909 season. Thomas immediately prospered with Philadelphia’s “inside” game, and was the Athletics’ primary backstop as they captured World Series victories in 1910 and 1911. He then transitioned to coaching and team captaincy as his playing career ebbed away. In these capacities, Thomas was a divisive figure as the era’s great Athletics team fell from championship heights. Afterwards, Thomas remained a Mack loyalist, and coached and scouted for the organization until the Athletics left Philadelphia in 1955.

A weak-armed washout from two other American League teams, catcher Ira Thomas was purchased by Connie Mack prior to the 1909 season. Thomas immediately prospered with Philadelphia’s “inside” game, and was the Athletics’ primary backstop as they captured World Series victories in 1910 and 1911. He then transitioned to coaching and team captaincy as his playing career ebbed away. In these capacities, Thomas was a divisive figure as the era’s great Athletics team fell from championship heights. Afterwards, Thomas remained a Mack loyalist, and coached and scouted for the organization until the Athletics left Philadelphia in 1955.

Ira Felix Thomas was born on January 22, 1881, in Ballston Spa, New York. His parents, Lugy and Selinda, were French-Canadian emigrants. Lugy worked in the forging trades, Selinda as a housewife. The Thomas household lay a mile from Abner Doubleday’s birthplace.

Alphonse, an older brother, was a gifted pitcher as a boy. Their mother, Ira remembered years later, “was determined that no stone should be left unturned in assuring a successful career for Al and if he needed practice he should get it.” But young Ira had no interest in the game and shirked catching his brother. To encourage the reluctant lad towards the sport, his mother gave Ira “one of the heartiest and most thorough spankings I ever had, and after that Al got all the practice he needed.”1

Shortly before the turn of the century, the family moved to Collinsville, Connecticut. By 1902, the two boys were playing in the Class D Connecticut League: Al with Springfield, Ira with Hartford. Yet Al’s arm soon gave out and, Ira recalled, “left the baseball burden of the family on my shoulders.”2

By 1903, Thomas was “developing into the premier catcher of the League,” and the Newark club of the Class A Eastern League purchased him.3 But the youngster jumped his reserve back to Hartford, and Newark, after re-establishing its hold on him, sold him to league rival Providence for the 1904 season. There, for the next two seasons, Thomas continued to progress, earning praise as “an excellent backstop and good thrower for a young catcher.”4

As part of an 11-player, $20,000 spending spree, the New York Highlanders purchased Thomas in mid-August 1905, to report after the season. On August 25, sliding into third base during a game at Rochester, he was dealt a crippling blow. “The third baseman jumped on me,” Thomas recalled, “and his spikes tore all the muscles off my arm and shoulder.”5

Despite limited prospects for a speedy or full recovery, New York manager Clark Griffith kept Thomas on the 1906 Highlander squad. The rookie appeared in only 44 games, hit .200, threw out 44% of would-be base stealers, and did not threaten Red Kleinow for the first-string catcher spot.

Thomas was re-inventing his game and, in the process, emerging as a cerebral major leaguer. “I started studying the mannerisms of base runners. I got so I could tell by their peculiarities what they would do.”6 He engaged teammates with a “more or less continuous conversation” about strategy, and became a subtle, scheming chatterbox behind the plate.7

The Highlanders challenged the White Sox for the pennant in 1906, finishing second with a 90-61 record. But in 1907 the team slipped to a 70-78 fifth-place finish. Thomas appeared in 80 games, hit only .192, and threw out 49% of would be base stealers. He came under fire in the New York papers. It was reported that he did not exist peacefully with irascible shortstop Kid Elberfeld, who complained he had to block off too many runners due to erratic throws from Thomas.8

Then there was his difficulties with high foul pop-ups. Was it attributable, one Highlander opined, to “hypermetropic astigmatism”? Or, as one observer thought later, was Thomas somewhat cross-eyed? Whatever the cause, sportswriter Hugh Fullerton suggested in 1910, Thomas circled under such flies “like a chicken with the blind-staggers.”9 The pop-ups did not always find their way to his mitt.

New York purchased well-regarded catching prospect Walter Blair late in the season. Detroit Tigers manager Hughie Jennings, seeking catching depth after Charley Schmidt performed below expectations in the 1907 World Series, bought Thomas in December.

Thomas had enjoyed working under the wily Griffith, but clashed with the emotional Jennings in 1908. “He would stand up in front of the stand and yell at his catchers when some batter made a hit,” Thomas wrote years later. “The catcher always called for the wrong pitch.” After one such incident, the strapping 6-foot-2 Thomas strode over to the smaller Jennings and said, “If you ever yell at me from the stand I’ll knock your head off.”10

Thomas played in only 40 games with the Tigers in 1908, mostly when the team faced left-handers, who Schmidt struggled against. As a result, the right-handed Thomas hit a robust .307. But he threw out only 28% of opposing base thieves, lending credence to those who had predicted that, without Elberfeld working on his behalf, he would struggle with the running game.

Detroit again prevailed in the 1908 American League race, and again were steamrolled by Chicago in the World Series. The sole Tigers victory came in Game Three. Southpaw Jack Pfiester started for the Cubs, so Jennings started Thomas. The Tigers romped 8-3. Thomas contributed a key two-out RBI and nailed three of five would-be base stealers.

Despite his fine postseason showing, Thomas was determined to leave the Tigers. That was all right with Hugh Jennings, who considered the catcher a “troublemaker” for advising his roommate, the reticent rookie Ed Summers, to ask for a raise.11

Connie Mack needed a catcher. Longtime Athletics backstop Ossee Schrecongost had faded, and was let go late in the 1908 season. Doc Powers, Mack’s other catching mainstay, was 38 years old. After Powers came sore-shouldered Bert Blue and unproven Jack Lapp. That offseason, Mack asked Detroit about the availability of Schmidt and Thomas. Told only Thomas was available, Mack purchased him for $4000.12

The overall Philadelphia effort to stop the running game would greatly assist Thomas, whose throwing arm was still average at best. Ex-catcher Mack assigned primary responsibility in stopping base stealers to his pitchers. In addition to the pitchers holding runners, the entire team studied opposing players on the bases, looking for tell-tale tics and habits. Such crafty strategizing was characteristic of Mack’s squads. Thomas, calling his new teammates “the brightest bunch of ballplayers I’ve ever met in one team,” quickly felt at home.13

Powers caught the first game of the 1909 season, fell victim to intussusception, and died two weeks later.14 Thomas was now unquestionably the Athletics’ first-string catcher. Mack purchased journeyman Paddy Livingston for catching depth.

Thomas asked Mack’s permission to catch all 22 games against the Tigers. The request was granted. Amongst the intelligence Thomas conveyed to his new teammates was that Tigers first baseman Claude Rossman lacked confidence in his throwing ability. The Athletics preyed upon Rossman’s weakness and took the initial series between the teams. Through July 11, Thomas started all 11 matches versus his former team. The Athletics were 8-3 against Detroit, and stood a half-game behind the Tigers with a 45-27 record.15

A few weeks later, Thomas suffered a broken thumb from a foul tip and was out for a month. Detroit eventually held off Philadelphia, and the Athletics finished second at 95-58. Thomas caught 84 games, hit .223, and threw out 49% of opposing base stealers.

Fractured digits characterized the era’s catching profession, putting emphasis on positional depth. Thomas again broke his thumb in 1910, then suffered a back injury. He played in only 60 games, hitting .278, and throwing out 47% on the base paths. Lapp played in 71 games, Livingston in 37.

This distribution of backstopping duties also reflected relationships between Mack’s pitchers and catchers. Jack Coombs was Thomas’s closest friend on the team, but the pitcher maintained Lapp’s smaller frame allowed him to better spot his pitches. A review of Coombs’s 102 regular-season starts between 1909 and 1911 shows Lapp indeed started in 63 (62%) of them. Livingston volunteered to catch Cy Morgan’s curves and spitters, and started 47 (52%) of the pitcher’s 90 starts in the same three-year period. Thomas was favored by Harry Krause (41 of 51 starts over the same timeframe, 80%), Chief Bender (57 of 81 starts, 70%), and Eddie Plank (64 of 95, 67%).16

At bat, Thomas stood in a crouch. “Thomas bends between his shoulders and his hips, his back assuming a camel-like hump.”17 Like all of Mack’s catchers in this era, he batted eighth in the lineup, behind Jack Barry. Thomas and the shortstop, one contemporary believed, “worked the hit-and-run more successfully than any other players” on the team.18

The Athletics comfortably took the American League pennant in 1910 and faced Chicago in the World Series. Cubs catcher Johnny Kling had built a sterling reputation in the 1907 and 1908 postseasons, while his teammates had terrorized Detroit on the base paths, stealing 15 bases in each Series. Thomas was thought to be outclassed.

But the Cubs were aging, with their regular-season stolen base totals declining steadily since 1906. They also poorly scouted the Athletics. Mack, on the other hand, sent a detail of players to study the Cubs when they visited the Phillies in September.19

Philadelphia hosted Game One on October 17. Bender allowed only two base runners in the first eight innings: a Frank Schulte single in the first, and a walk to Schulte in the fourth. Both times, the speedy Cub bolted for second. Both times, the first on a pitchout, Thomas retired him. Bender coasted to a 4-1 victory; Thomas muffed a foul pop-up to assist Chicago’s ninth-inning run.

Based on Thomas’s experience and his showing in Game One, Mack selected him instead of Lapp to catch Coombs in Game Two. Colby Jack struggled with the strike zone. In the third inning, with a man on second, on a would-be wild pitch, “Thomas made a brilliant catch by spearing the ball with his bare hand.”20 The Cubs ran on him only once, in the fourth, when Joe Tinker was “out nine feet” on another pitchout.21 The Athletics rolled to a 9-3 victory.

Coombs and Thomas worked together again in Philadelphia’s 12-5 victory two days later. In Game Four, Bender and Thomas were battery mates in a ten-inning 4-3 loss to the Cubs. Thomas then reportedly lobbied Mack for Lapp to rejoin Coombs for Game Five.22 Mack agreed, and the Athletics closed the Series with a 7-2 win. Thomas finished the Series 3-for-12 at the plate, allowing only two of eight stolen base attempts to succeed. Bender and Coombs complied a 2.95 ERA in the four games he caught.

In 1911 the Athletics spotted the Tigers an early lead, but chased them down by mid-summer and comfortably took another pennant. Thomas enjoyed a career year, avoiding serious injuries, catching 103 games, hitting .273, and throwing out 51% of base stealers.

In the World Series that fall, the Athletics faced the Giants. John McGraw’s youthful team was relentless on the base paths, stealing a post-1900 record 347 bases in 1911. “In nearly all forecasts,” preceding the Series, Francis Richter observed, “the base-stealing ability of the Giants was regarded by the critics as a great factor in their favor.”23

Philadelphia won the Series in six games. Thomas caught four of them, going 1-for-12 at the plate, with Bender and Plank posting a 1.03 ERA under his watch. In the first inning of Game One, Larry Doyle pilfered second on his off-target throw on a pitchout. That was the only stolen base Thomas permitted in four attempts. Lapp caught Coombs in Games Three and Five, and only two of the Giants’ seven stolen base attempts under his watch succeeded. Of the pair’s success, Mack biographer Norman Macht writes, “They noticed that the Giants faked a lot of false starts on the bases. By watching the footwork, they figured out when the runners were faking and when they intended to go.”24

The Athletics fell to a third-place finish in 1912. Thomas appeared in 48 games—only a few after July—and eventually was diagnosed with tonsillitis in September.25 Excepting Plank, the veteran pitchers’ performances fell off. Then, at the start of the 1913 season, the workhorse Coombs was lost to illness.

A rebuilding of the staff was necessary, and the Athletics’ 1913 fortunes largely rested upon a gaggle of kid pitchers: 24-year-old Carroll Brown, 20-year-old Joe Bush, 21-year-old Byron Houck, 19-year-old Herb Pennock, 22-year-old Bob Shawkey, and 22-year-old Weldon Wyckoff. Complementing the young twirlers, heralded 23-year-old backstop Wally Schang arrived as well.

“Ira can get more out of a pitcher than any other catcher I ever knew,” Mack stated in 1911, “what he doesn’t know about handling pitchers isn’t worth knowing.”26 Two years later, Mack appointed Thomas as the de facto pitching coach. Behind Lapp and Schang, he appeared in only 22 games as the third-string catcher. The Athletics took down another American League flag, and again dispatched the Giants in the World Series.

Thomas had been for some time “the most enthusiastic member of the Mack congregation.”27 A noted abstainer, he chaperoned young players away from drink and other vices. His scouting contributions grew steadily over the years, and by 1913 he was a central resource in researching potential acquisitions, then vetting them as they arrived.28 To the press, Thomas demonstrated an unflinching faith in the Athletics’ way.

In March 1914, Mack named Thomas the Athletics’ captain, succeeding Danny Murphy, who was sold to Baltimore of the International League. The news “came as suddenly and surprising” to Philadelphia fans.29 Murphy might have been retained. Harry Davis, who had preceded Murphy as captain, might have been re-appointed. Or, instead of Thomas, Murphy, or Davis—all coaches with their playing days essentially behind them—Mack might have turned to his gifted second baseman, Eddie Collins.

Unlike Murphy and Davis, Thomas was not very popular with his teammates. He moralized too much. He needed to have the last word in a conversation. He sought publicity too frequently, and in print his contributions too often seemed exaggerated. These tendencies were likely more forgivable when Thomas had been an everyday player. But by 1914, much of the squad found him to be a killjoy and a blowhard.30

But the captaincy wasn’t a popularity contest. Mack saw in Thomas a record of leadership and mentoring. The role was largely analogous to a present-day bench coach, and thus would require some re-engineering if handed to an everyday player like Collins.31 Finally, the captaincy was loyalty rewarded. The Federal League threatened allegiances, and Mack needed someone who would place the Athletics above all else.

Thomas had once possessed the economic perspective of a player. In addition to advising Summers to seek more money, he had kicked (unsuccessfully) for greater pay when purchased by Mack. But Thomas had profited from an almost annual run of World Series checks, wisely invested in Philadelphia real estate, and harbored ambitions to one day join the magnate ranks himself. By 1913, as he was defending American League President Ban Johnson as “the ball player’s friend,” Thomas rose within the ranks of the nascent Players Fraternity, leading to lasting suspicions that he was a stalking horse for the magnates’ interests.32 In 1914, as the organization veered away from the more moderate actions he lobbied for, Thomas stopped paying his dues, choosing management over labor, and was expelled. His teammates, reportedly, were mostly unsupportive of the Fraternity, with Collins a notable exception.33

This anti-union stance angered much of baseball’s rank and file, with repercussions as the Athletics won their fourth pennant in five seasons, and faced the Boston Braves in the 1914 World Series. Boston out-scouted Philadelphia and were assisted by “several American leaguers” who gladly “told them everything they know about the Athletics’ weakness.”34 Then, as part of the Braves’ savage taunting of the Athletics during the Series, Mack and Thomas were greeted with “the continual shouting of ‘scab.’”35 But beyond the politics lay the simple truth that, as Thomas observed, the Athletics “were simply outplayed by the Boston team” in the four-game sweep.36

After the Series loss, Thomas came under considerable criticism from anonymous teammates in the press.37 In particular, it was reported that the team had been divided throughout the 1914 campaign into two factions: one loyal to Thomas, one loyal to Collins.38 Thomas had become a lightning rod. Collins was sold to the White Sox. Economics and loyalty—to team, not to captain—drove Mack’s actions.39

Nonetheless, when Mack “blandly announced” in February 1915 that Davis would succeed Thomas as captain, it was a tacit admission that the latter had been a polarizing figure the previous season.40 Thomas returned to the role of pitching coach. In this capacity, his prior reputation for tutoring young pitchers, which some felt had been inflated, was considerably tarnished in 1915.41 The Athletics collapsed to a 43-109 last-place finish, and the pitching staff’s 4.29 ERA was the worst in baseball. On June 18, Happy Felsch of the visiting White Sox spiked Athletics catcher Jim McAvoy in the eighth inning, and Thomas came in to catch the ninth in an 11-4 Philadelphia loss. It was his final appearance as a player.

After the Athletics suffered through another awful season in 1916, Thomas signed a five-year contract to manage the Williams College Ephs. He was, Ernie Lanigan estimated in 1919, “undoubtedly the highest paid college baseball coach at the present time.”42 Thomas remained at Williams for three years, while continuing to scout for Mack outside of his collegiate duties. In 1919, after the Williams season, Thomas took over from an ailing Charlie Frank to manage the Atlanta Crackers of the Class A Southern Association. But he was drawing an Athletics salary as well and, after four games, was forced to abandon the post due to baseball’s conflict of interest rules.43

Thomas was then drawn to an oil boom under way in northern Louisiana, leaving Harry Davis to take over at Williams for the 1920 season. The initial oil investments failed, but Thomas remained. In August 1922 he led a group of local businessmen to purchase the Shreveport Gassers of the Class A Texas League, with Thomas himself to manage the team in the 1923 season.44

The Gassers had been a last-place team in 1922 and, with Thomas at the helm for the next two seasons, they remained so. But if his managerial accomplishments were otherwise unimpressive, he did help to develop Al Simmons, mostly by working to instill a hustling work ethic into the youngster while leaving his natural hitting style alone.45

In late 1924, Thomas sold his holdings in the Gassers and returned to Philadelphia to again serve as Mack’s pitching coach. As a second Athletics dynasty emerged, he assisted in taming Lefty Grove’s wildness and helped George Earnshaw develop a changeup. When Philadelphia won three straight pennants beginning in 1929, Thomas was a key member of Mack’s pre-Series scouting contingent.46

After another dynasty fell apart, Thomas continued with the Athletics—first as pitching coach and scout, then exclusively scouting—for another two decades. Additionally, Thomas assisted the University of Pennsylvania baseball staff, led a baseball school for Philadelphia youth, was a mainstay on the local public speaking circuit, and maintained his oil and real estate investments.47 A bit beefier with each passing year, Thomas came down to breakfast every morning, his nephew recalled, “in a shirt and tie and coat no matter how hot it was” just like his “idol” Connie Mack.48

Katherine, his wife and “good right hand” for 44 years, passed away in 1948.49 The couple had no children. Thomas continued with the Athletics, even as Mack relinquished the manager’s role at the end of the 1950 season. After the 1954 season, the team was sold and moved to Kansas City. Thomas was asked to continue in a scouting role. However, while bedridden with injuries sustained in a car accident, Thomas was unceremoniously let go at the end of the 1955 season, after 47 years of service to the franchise. Connie Mack passed away months later.

The Yankees, his first major league team, added Thomas to their scouting staff for the 1956 season, after which he retired from baseball. On October 11, 1958, Thomas passed away in Philadelphia from heart disease. He was buried in the Holy Sepulchre Cemetery in Cheltenham, Pennsylvania. Ira Thomas shares this resting ground, some eight miles north of where Shibe Park stood, with Connie Mack.

Sources

I would like to thank Cynthia Franco of the DeGolyer Library at Southern Methodist University for her assistance in obtaining materials from the Norman Macht baseball research collection related to Ira Thomas. (Credit: DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, A2010.0038.)

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Thomas’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

Notes

1 F. J. Kennedy, “Ira Thomas, One of Connie Mack’s Trump Cards,” Baseball Magazine, November 1913, 46.

2 Ibid, 47.

3 Tim O’Keefe, “Happy Hartford,” Sporting Life, May 30, 1903, 1.

4 (Jersey City, New Jersey) Jersey Journal, May 19, 1904, 19.

5 For the Highlanders’ signing, see “Gossip of the Game,” Boston Herald, August 22, 1905, 5. For an account of the Rochester game, see “Rochester 2, Providence 1,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, August 26, 1905, 13. For Thomas’s memories, see Kennedy, “Ira Thomas.” Note that, in Kennedy’s piece or elsewhere, Thomas did not specifically mention the game or opponent. However, the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle account of the game mentions an injury to his shoulder in a collision at third. Thomas, after this game, disappears from Providence box scores, and by August 31, it was mentioned in the press that he had been sent home to recuperate.

6 Franklin W. Yeutter, “Viewing the Sports Parade,” 1936 newspaper article in Thomas’s Hall of Fame file.

7 F. C. Lane, “The Greatest of all Catchers,” Baseball Magazine, April 1913, 46.

8 “Were Bitter Enemies,” Washington Post, December 23, 1907, 8; “McGraw will Call on Tenney This Week,” Boston Journal, December 30, 1907, 8.

9 Washington Times, January 1, 1908, 8; “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 17, 1911, 8; Hugh S. Fullerton, “Sox’ Bad Judgement at Bat and on Bases Hand Athletics Game,” Chicago Examiner, August 4, 1910, 7.

10 Thomas to Ernie Lanigan, June 20, 1958, in Thomas’s Hall of Fame file.

11 Ibid; “Mack Thinks Well of Reorganized Athletics,” (Cleveland) Plain-Dealer, May 25, 1909, 8.

12 “Athletics Get Thomas,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 15, 1908, 10.

13 Norman Macht, Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2007), 430-433, 472.

14 Ibid, 438-439.

15 “Newsy Gossip of all the Sports,” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, March 26, 1909, 10; Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 441-442.

16 These statistics per Retrosheet.org and The Sporting News box scores; for a contemporary appreciation of these relationships, see Billy Evans, “Superstition Rules Many Star Pitchers,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 13, 1910, 57.

17 Washington Times, July 23, 1906, 8.

18 Per a “Western contemporary” quoted in Francis C. Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, November 25, 1911, 11.

19 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 480; Eddie Collins, “1910 World Series, Collins’ First, Provided Biggest Thrill of His Career in Base Ball,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, January 7, 1927, 34.

20 (Chicago) Inter-Ocean, October 19, 1910, 2.

21 Thomas S. Rice, “Looks Pretty Soft for Athletics Now,” Washington Times, October 19, 1910, 12; “World’s Series Notes,” Sporting Life, October 29, 1910, 6.

22 Tim Karp, “Every Little Moment,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, March 14, 1911, 11.

23 Francis C. Richter, “The Great 1911 Battle of the Major Giants,” Sporting Life, November 4, 1911, 7.

24 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 529.

25 Senator [pseud.], “Griffmen Anxious to Finish Second,” Washington Times, September 26, 1912, 14.

26 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Ira Thomas Given Big Slice of Credit for Success of A’s,” The Sporting News, November 24, 1932, 3.

27 “How Ira Thomas Dopes Athletics to Beat Cubs,” Washington Post, September 25, 1910, 46.

28 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 578-579.

29 “Thomas to Lead Macks, Dan Murphy Released,” Philadelphia Inquirer, March 7, 1914, 12.

30 On Thomas’s unpopularity see, “Collins Sold Because Of Friction With Ira Thomas,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times, December 9, 1914, 7; Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 618-620; “Noted of the Nationals,” Washington Post, September 17, 1911, 47.

31 Francis C. Richter, “Athletics Surprise,” Sporting Life, September 5, 1914, 10.

32 “The Magnate From a Player’s Viewpoint,” Baseball Magazine, January 1913, 56; Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 606; Robert F. Burk, Never Just a Game: Players, Owners, and American Baseball to 1920 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 193.

33 Macks and Naps Will Play Ball,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 21, 1914, 12: Louis A. Dougher, “Today’s Sportorial,” Washington Times, September 5, 1914, 10; “Have No Use for Fultz,” Sporting Life, September 5, 1914, 3.

34 Sporting Life, October 24, 1914, 10.

35 “Braves Got ‘Goats’ of Mack and His Athletics,” Washington Herald, October 18, 1914, 39.

36 Philadelphia Evening Ledger, October 17, 1914, 16.

37 “Collins,” Reading (Pennsylvania) Times; “Captain Thomas, Skipper of the Good Ship ‘Connie Mack,’ 34 Today,” Trenton Evening Times, January 22, 1915, 17.

38 James Clarkson, “’Collins Sure to Manage Sox,’ Says Clarkson,” Chicago Examiner, December 9, 1914, 13.

39 Macht, Mack and the Early Years, 649-672.

40 “Mac Announces That Harry Has Succeeded Thomas as Team’s Captain,” Philadelphia Inquirer, February 26, 1915, 10.

41 Norman Macht, Connie Mack: The Turbulent & Triumphant Years, 1915-1931 (Lincoln: University of Nebraska, 2012), 27-30.

42 “Declares Thomas is Highest Paid Coach,” North Adams (Massachusetts) Transcript, April 1, 1919, 11.

43 “Ira Thomas, Now Atlanta Catcher, Stirs Up Trouble in Southern League,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 18, 1919, 19.

44 “Harry Davis Drills Williams Nine,” Philadelphia Evening Ledger, March 10, 1920, 10; “In Business,” (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) Evening News, April 30, 1920, 21; “Ira Thomas Slated to Manage Shreveport,” Philadelphia Inquirer, August 8, 1922, 17; Macht, Mack: The Turbulent & Triumphant Years, 313.

45 Macht, Mack: The Turbulent & Triumphant Years, 313-316.

46 “Ira Thomas Will Return as Coach,” Trenton Evening Times, November 16, 1924, 38; Nasium [Wolfe], “Ira Thomas”; George Moriarty, “Thomas, A’s Scout, Gets Tips on Cubs Month Before Series,” (Washington, DC) Evening Star, October 16, 1929, 37; Macht, Mack: The Turbulent & Triumphant Years, 400, 587.

47 Edgar G. Brands, “Between Innings,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1936, 4.

48 DeGolyer Library, Southern Methodist University, Dallas, Texas, A2010.0038.

49 “Funeral Tomorrow for Wife of Ira Thomas,” (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania) Evening News, December 28, 1948, 21.

Full Name

Ira Felix Thomas

Born

January 22, 1881 at Ballston Spa, NY (USA)

Died

October 11, 1958 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.