Luis E. Tiant

Luis Eleuterio Tiant (1906-1976) was one of the finest pitchers that Cuba has ever produced. So was his son, Luis Clemente Tiant, who won 229 games in the major leagues from 1964 through 1982 – more than any of his countrymen. When asked about his namesake, Luis C. said in 1974, “He was a better pitcher than I am.”1 The following year, the father said, “My son is better than I am.”2

Luis Eleuterio Tiant (1906-1976) was one of the finest pitchers that Cuba has ever produced. So was his son, Luis Clemente Tiant, who won 229 games in the major leagues from 1964 through 1982 – more than any of his countrymen. When asked about his namesake, Luis C. said in 1974, “He was a better pitcher than I am.”1 The following year, the father said, “My son is better than I am.”2

It wasn’t just mutual modesty, though – in October 1975, Luis C. emphasized, “He was better than me. Everybody in Cuba knows that.”3 That statement came just before Luis C.’s most notable performances, his brilliant efforts in the 1975 World Series. The color barrier denied Luis E. the opportunity to play in the majors. Yet even after 1975, top-level judges of talent in Cuba – such as Agustín “Tinti” Molina, the man who spotted Luis E. – favored the father.4

Leaving this debate aside, though, there’s no question that Luis E. Tiant was a first-rate pitcher. Hall of Famer Monte Irvin said that the elder Tiant would have been a “great, great star” in the majors.5 Instead, Luis E. played in Cuba, the Negro Leagues, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico, as well as barnstorming teams, from 1926 through 1948.

The two pitchers differed in some basic ways. The father was a lefty; the son was a righty. The father was small for a pitcher at 5-feet-10 and 150 pounds – along with the obvious “Lefty,” one of his nicknames was “Sir Skinny.” The son grew to six feet even and was built more thickly (his big-league baseball cards mostly listed him at 190 pounds). But they were mirror images in terms of their herky-jerky, corkscrew pitching motion. This deceptive style also gave both men the benefit of an excellent pickoff move.6 Cuban baseball historian Roberto González Echevarría described how the elder Tiant “was fond, for example, of walking lightning-fast Cool Papa Bell on purpose, just to put on a show trying to keep him from stealing.”7

The ESPN Pro Baseball Encyclopedia summed up Luis E.’s repertoire well. “The elder Tiant had control of three power pitches (fastball, curve, slider), but his best pitch was a screwball. He worked with a junkballer’s attitude and his mix of skills and approach served him well, especially in big games.”8 The same, minus the screwball, was true of Luis C.

“The old man could hit and he could wet up those pitches,” said Al Smith. Smith faced Luis E. in 1947 as a teenaged member of a Negro League opponent, the Cleveland Buckeyes. In 1964, his last season in the majors, Smith was a teammate of the rookie Luis C. with the Cleveland Indians.9

Luis E. also had a hard edge – he could be a headhunter at times. Negro Leaguer Ted Page liked to tell the story of how he once got a hit off a Tiant curveball in his first at-bat. The next time up, Tiant hit Page in the head and knocked him out. When Page came to, he heard Tiant saying, “You no hit that one too well.” Decades later, Page still had a bald spot from the beaning.10

Luis Eleuterio Tiant Bravo was born on August 27, 1906 in La Habana (Havana), the capital of Cuba. His father, a policeman, was also named Luis Tiant. Five generations of Tiant men have now carried this given name, extending through Luis Clemente Tiant’s son and grandson. His mother, Señora Bravo, was a housewife.11 Luis E. was the eldest of nine children. He had three brothers (René, Juan, and Hilario) and five sisters (Conga, Chicki, Cristina, Adelaïda, and Quilla).12

Luis C. Tiant never knew much about his father’s youth and how he came to baseball. One may imagine, though, that given the sport’s longstanding high popularity in Cuba, Luis E. grew up playing in the placeres, or sandlots. Luis C. did know, however, that his uncle Hilario was also a very good player – but Hilario did not want to sign with a team and remained a carpenter instead.13

Available sources indicate that Luis E. Tiant’s professional career began in 1926. According to Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball by Jorge Figueredo, he pitched in six games for a club billed as “Cuba”. Figueredo’s compilation shows that Tiant pitched only on occasion in the main Cuban league from 1926 through 1930 – 11 games in all, with none in either the winters of 1927-28 or 1929-30 (though by some accounts, he was a member of the 1929-30 league champions, Cienfuegos). Information on this period is scarce, however, and Luis C. could not complement it.

Luis E. Tiant first played in the U.S. in 1928, with a barnstorming team called the Havana Red Sox. Author Alan Pollock provided background on this team and Tiant’s time with them. Pollock’s father was Syd Pollock, a notable impresario of black baseball. Syd booked and promoted the Havana Red Sox for many years; he then purchased the franchise after the 1928 season. “In 1931, the Havana Red Sox became the Cuban House of David, which became the 1932 Cuban Stars.”14 Newspaper accounts from the Afro-American in 1931 and 1932 support Alan Pollock’s timeline. In April 1932, that paper described Tiant as “ace of [the] Cubans’ hurling staff.”15 Another article, from July 1932, was written by Syd Pollock himself and detailed how tough the business of baseball was amid the Great Depression.16

Cuba’s economy and baseball also suffered in the early ’30s. Political turmoil was another factor, as Roberto González Echevarría noted. The 1933-34 season was not held, and Tiant did not pitch at home in either 1932-33 or 1934-35. He lost some prime seasons.17

Nonetheless, he made his mark. “When Dad spoke of the best pitchers he ever saw, he ranked Lefty Tiant at the top,” Alan Pollock wrote. “My brother Don was there the day Lefty Tiant gave Mom the beautiful silver crucifix on a silver chain she kept until she died. As star of Dad’s Cuban teams, he was billed as Lefty Grove Tiant, and the irony of that billing echoes in words my brother Don once wrote me: “Lefty [Tiant] was the greatest pitcher I ever saw, better than Lefty Grove or Lefty Gomez.” Pollock continued, “Tiant played for Dad until Alejandro Pómpez stole him in 1935 for the New York Cubans.” 18

Alex Pómpez, the Cuban-American entrepreneur who later entered the Baseball Hall of Fame, brought his New York Cubans franchise into the Negro National League in 1935. That year, Pómpez assembled a powerful team, led by player-manager Martín Dihigo. Tiant’s skill was widely recognized; he got more votes than any other pitcher in the selection of squads for the East-West All-Star Game.19 In that game, at Chicago’s Comiskey Park on August 11, Tiant allowed three runs in two innings of relief. The West later won, 11-8, on a game-ending three-run homer in the 11th inning by Mule Suttles.20

The Cubans won the second-half pennant in 1935 and faced the Pittsburgh Crawfords for the league championship. The series went to seven games, and Tiant got the call to start the decisive match. He and the Cubans were leading 7-5 after seven innings, but in the eighth, “Sir Skinny” tired, allowing home runs to Josh Gibson and Oscar Charleston. After Sam Bankhead reached base, Cool Papa Bell singled him in with the decisive run. As Negro League historian Larry Lester wrote, “This year’s edition of the Pittsburgh Crawfords has been called by many baseball historians the greatest Negro League team ever and has often been compared to the 1927 Yankees. Regardless, they struggled to beat baseball’s all-star contingent of mostly Latin Americans.”21

Shortly afterward, on September 29, the Cubans played the Babe Ruth All-Stars in a doubleheader at their home park, Dyckman Oval in upper Manhattan. The 40-year-old Bambino (whose big-league career had ended that May) reached Tiant for a double in the first inning of the opener. “But that was it!” said Larry Lester. “Tiant shut down the Babe Ruth All-Stars on four hits, as the Cubans won, 6-1.”22

After the 1935-36 winter season ended in Cuba, Tiant got to face major-league competition. As was often the case in those days, big-league clubs played exhibition games in Cuba during spring training. In March 1936, the St. Louis Cardinals visited for a four-game series against the Havana All-Stars. On March 5, Tiant started the first game of the set, before a crowd of 14,000 that included the President of Cuba, José A. Barnet. The All-Stars won, 13-8. Tiant took a 6-1 lead into the eighth inning, but the Cardinals erupted for seven runs, knocking him out. The Cuban squad then responded with seven scores of their own in the bottom of the eighth.23

The New York Cubans did not operate during the 1937 or 1938 seasons. Special prosecutor Thomas Dewey had Alex Pómpez in his sights for involvement with the numbers racket in New York, and Pómpez hid out in Mexico for a portion of this time. His players, Tiant among them, looked mainly to Latin America for employment. During 1937, opportunity arose in the Dominican Republic.

As has often been chronicled, 1937 was a remarkable year in Dominican baseball. The season was dedicated to the re-election of dictator Rafael Trujillo, and Ciudad Trujillo assembled a powerhouse team, luring the best Negro Leaguers of the day to come down. The league’s other teams competed, at least to a degree. Águilas Cibaeñas of Santiago signed Tiant plus two of his countrymen, Dihigo and Santos Amaro. Tiant posted a 1-3 record.24

Santos Amaro’s son, Rubén Amaro, also went on to play major-league baseball. In 2014, Rubén Amaro said of Tiant, “I do remember him as a pitcher even though I was very young [Amaro was born in 1936, so his memories date from the 1940s]. He was good friends with Dad. He always dressed in a suit with a hat on. Skinny, big nose, lots of deception in his windup.”25

Dominican pro baseball collapsed after the 1937 season, not to reappear until 1951. From 1938 through 1942, the available historical record for Tiant is very patchy. Baseball-reference.com shows no action for him in the Negro Leagues in 1938 or 1942, just nine games for the New York Cubans in 1939, and a mere one in 1940. One possibility, though unsupported at present, is that Tiant went to Venezuela in 1938 (as did various other black ballplayers, including Santos Amaro).

Tiant did, however, play outside the Negro Leagues too. For example, in May 1939, the Brooklyn Eagle noted that the “clever southpaw” had defeated the semi-pro Brooklyn Bushwicks. That article also described Tiant as a former member of the Cubans; instead, he was listed as playing for the Cuban Stars in the Metropolitan Baseball Association.26 The following month, though, the Pittsburgh Courier described “the weird slants of Lefty Tiant” in a Negro National League game between the New York Cubans and Baltimore Elite Giants at Yankee Stadium.27

Though the records may well be incomplete, it’s possible that Tiant might also have missed some time with arm problems. Another conjecture is that he may have been at home in Cuba for family reasons. On November 23, 1940, Luis and his wife, Isabel Rovina Vega, welcomed the birth of their only child, Luis Clemente. (Records of their wedding date have never surfaced, and Luis C. Tiant did not know it.)

The new father was a member of the Cuban league champion, Havana, in the 1940-41 season. The club was managed by Miguel Ángel “Mike” González. Tiant then played in Mexico in the summer of 1941. He pitched 82 innings in 16 games for Veracruz Águila, posting a record of 2-5 with a 5.05 ERA.

In the winter of 1942-43, Tiant once again did not pitch in Cuba. However, he was definitely with the New York Cubans in the summers from 1943 through 1947. He also returned to Cuban winter ball, pitching two seasons with Marianao and two with Cienfuegos. He took part in a memorable 20-inning affair on December 2, 1943 – the longest game in the history of Cuban professional ball. Tiant went 15 innings, the first 14 scoreless, and allowed just one unearned run. The winter of 1945-46 was a high point. Cienfuegos, managed by Adolfo (Dolf) Luque, won the league championship. The international pitching staff included Sal “The Barber” Maglie, fellow Cuban Adrián Zabala, and Canadian Jean-Pierre Roy.

Tiant had his most notable Stateside season in 1947, winning 10 games and losing none for the Cubans. There were two East-West All-Star games that year, and he appeared in both of them. In Game One on July 27, at Comiskey Park, the West knocked Max Manning out of the box in the third inning. Tiant pitched 2 2/3 scoreless innings in relief. Two days later at the Polo Grounds in New York City, he relieved Rufus Lewis and allowed three runs in two innings.28

Tiant’s roommate that year was José “Pantalones” Santiago, then a young man of 18, who later pitched briefly in the majors from 1954 through 1956. Santiago told author Lou Hernández, “Tiant was already up there in age. He was at least 40, and his record was phenomenal. Tiant was a serious individual. Tiant did not have any vices; he did not smoke or drink. He did not speak too much to me about pitching. He was a lefthander and I was a right-hander. Tiant had an extraordinary screwball. And an extraordinary pickoff move to first base.”29 Santiago alluded to a funny story that Negro Leaguer Henry Kimbro told another author, Brent Kelley, in clearer detail. “[Tiant] was pitching for Cuban Stars, Fred McCreary was umpiring, Goose Curry was the hitter. Tiant went up and down and grunted and throwed that ball and Goose Curry swung and said, ‘Jesus Christ! Man, how’d I miss it?!’ Fred McCreary said, ‘I oughtta call you out. That man throwed to first base.’”30

The Cubans faced the Cleveland Buckeyes in the 1947 Negro World Series. After the opening game at the Polo Grounds ended in a tie because of rain, Tiant started the next game at Yankee Stadium. He got the hook after allowing three runs in the first inning but got no decision; Cleveland eventually won 10-7. In Game Five at Chicago’s Comiskey Park, Tiant was again ineffective, giving up four runs in three innings. The Cubans came back to win, 6-5, which also clinched the series and gave Alex Pómpez his only championship.31

Tiant finished his career in Cuban winter ball in the 1947-48 season, with an “alternative” league called La Liga Nacional (or Players Federation). The circuit, which lasted just one year, featured players who had become “outlaws” in the US because of their association with the Mexican League in 1946. Tiant recorded no decisions in 16 games for two teams, Santiago and Cuba. Luis C., then a seven-year-old boy, remembered watching from the dugout and becoming friends with a teenager named Rodolfo Arias.32 Arias eventually turned pro; the lefty pitched in 34 games for the Chicago White Sox in 1959.

All told, Luis E. Tiant played at home in 16 seasons (as documented). He compiled a record of 42 wins and 60 losses, leading the league in defeats five times. Unfortunately, his other Cuban statistics are largely missing or incomplete, and the same is true in general of the Negro Leagues. As a result, we cannot quantify what Roberto González Echevarría described as “uncanny control.”33

Tiant went back to Mexico in 1948. He started off with San Luis Potosí, but the franchises there and in Tampico were folded as the Mexican League consolidated in response to financial difficulties.34 He then joined Monterrey. In total, Tiant appeared in 18 games, all in relief. He logged 58 1/3 innings, going 4-4 with a 5.55 ERA. He appears to have played that fall in La Liga Peninsular, on Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula, not far from Cuba.35 However, Luis E. Tiant then retired from baseball. As Luis C. told author Tom Boswell (then a columnist) in 1975, “He come back to Havana but he never go back to the game no more. Never. It’s cruel.”36

As author Mark Frost described, Tiant’s meager savings were just enough to buy a half-interest in a truck. His brother-in-law owned the other half and they went into business together moving furniture. Isabel worked as a cook. Their son loved baseball, but Luis E. was reluctant to let the youth pursue a pro career in the sport because he remembered the persecution he had faced in the U.S. while earning paltry pay. Isabel was able to convince her husband, however, and so the younger Tiant went ahead and began to play for the Mexico City Tigers in 1959. The scout who signed him was Bobby Ávila, the Mexican second baseman, who was then still an active major-leaguer. Ávila and Luis E. had known each other for a long time.37

Luis C. also played one season (1960-61) in the Cuban winter league – it was the league’s last, because Fidel Castro’s regime abolished professional baseball. He left Havana in 1961 to return for his third season with the Tigers. Later that year, Luis E. warned his newlywed son not to come back home because of the change in the political climate. They did not see each other again for more than 14 years. They did exchange letters and talk often on the telephone, however, and Luis E. sometimes gave his son pitching advice. “He reminds me to keep skinny and throw hard,” was one quote from 1966.38

In the winters of 1966-67 and 1967-68, Luis C. played in the Venezuelan league for the Caracas Leones. Two fellow Cubans – manager Regino Otero and coach Rodolfo Fernández – both knew his father well from their playing days together. In fact, Fernández (a righty pitcher) had been on the same staff as Luis E. with the New York Cubans for several years. Both men told Luis C. to his face, “You are a good pitcher, but your father was better.”39

The separation from his parents clearly weighed on Luis C.40 The best that he could manage, however was some time with his mother in Mexico City in the fall and winter of 1968. Luis E. was allegedly jailed to ensure her return.41 There is uncertainty on this point, though; as Luis C. said in 2014, this was not a topic one discussed.42

In early 1975, Luis C. talked about the situation with Joe Fitzgerald of the Boston Herald. “How much longer? My father’s seventy [sic] now and he’s not well. Yet he still works in a garage down there, and here I am living like this, and I can’t send him a dime for a cup of coffee. I listen to people in this country complain that they don’t like this, they don’t like that. I’ve got friends up here [fellow Cuban expatriates] whose parents have died and they couldn’t go home to bury them. What can ever hurt like that? Now all the time, I think about my father dying and. . .”43

In addition to Luis E.’s job pumping gas (he had also worked as a security guard at a construction company), Isabel continued to work as a housekeeper.44 They were still living in Havana.45

Soon thereafter, things changed. During the first week of May 1975, U.S. Senator George McGovern made an unofficial visit to Cuba to see for himself what was happening in the nation and to meet with Castro.46 McGovern also bore a letter from his fellow Senator, Edward Brooke of Massachusetts, requesting the favor of a Tiant family reunion in Boston. Sen. Brooke and Luis C. Tiant were friends.47 What’s more, Ruth Seldon, the younger sister of Brooke’s mother, was married to Alex Pómpez. In his 2007 autobiography, Brooke wrote fondly of his vacations in Harlem with his Aunt Ruth and Uncle Alex. He was aware of Pómpez’s activity in baseball. It’s not farfetched to think that he may have had firsthand memories of Luis E. Tiant.48

Sen. Brooke’s letter to Castro suggested that “Luis [C.’s] career as a major league pitcher is in its latter years” – which turned out to be far from true – and added that “he is hopeful that his parents will be able to visit him during this current baseball season.”49

Castro granted the request. As the story broke in the U.S., Luis C. was “overjoyed, but cautious. He didn’t want to say too much.” He’d wanted to go back to Cuba before but was afraid that he would not be able to leave again.50

Although the diplomatic mill ground slowly, in August Luis E. and Isabel flew to Mexico City. It took several days more for their visas to be finalized, but finally they flew to Boston. The meeting between the Tiants, their son, their daughter-in-law María, and three grandchildren was a deeply emotional time.51

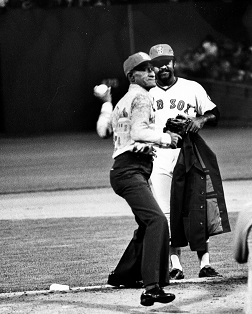

On the night of August 26, 1975, Luis E. finally got to see his son perform in person in the major leagues. (He had previously caught occasional TV broadcasts.)52 Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey invited the old pitcher, who was still whippet-thin, to throw out the first pitch against the California Angels.53 It was a huge story in Boston – Luis C. was extremely popular for his personality and excellent pitching. It was national news as well. The Associated Press covered the story as follows.

On the night of August 26, 1975, Luis E. finally got to see his son perform in person in the major leagues. (He had previously caught occasional TV broadcasts.)52 Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey invited the old pitcher, who was still whippet-thin, to throw out the first pitch against the California Angels.53 It was a huge story in Boston – Luis C. was extremely popular for his personality and excellent pitching. It was national news as well. The Associated Press covered the story as follows.

“They stood together, father and son, on the pitcher’s mound at Fenway Park. The older man, beaming, acknowledged the cheers of the crowd as he had in his playing days nearly 30 years ago.

Then Luis Tiant Sr. took off his coat and handed it to his boy, went into his windup and delivered a low fastball to Boston catcher Tim Blackwell.

Not satisfied with the form that may have lost something over the years, Tiant called for the ball again and fluttered a knuckleball across the plate as 32,086 voices roared. It was Luis Tiant of the New York Cubans, circa 1927-48, all over again.

He reclaimed his coat, whispered something in his son’s ear, and left. Luis Tiant Jr., of the Boston Red Sox, took the mound.

“He just told me, ‘Go get ’em. Don’t worry about me being here,’” the younger Tiant recalled.”54 Luis E. then joined Isabel, María, and grandchildren in the stands.55 It’s also worth noting that he told his son, perhaps not entirely in jest, that “any time they [the Red Sox] need him, he can go four or five innings.”56

Luis C. had an off night, giving up five runs in six innings and taking the loss as the Angels won, 8-2. After the game, though, he added, “Maybe he [Luis E.] will see me pitch in the World Series. I sure hope so.”57 Luis C. was right. He missed 10 days with a back problem – incurred while trying too hard to please his father.58 He lost just one more game during the rest of the 1975 season, though, helping the Red Sox to win the AL pennant and performing heroically in the Series against the Cincinnati Reds.

As one would expect, Luis E. was at Fenway Park to watch his son’s commanding 7-1 victory in Game One of the AL Championship Series against the Oakland A’s. He was on hand in the locker room as Luis C. iced down his arm after going all the way.59 He and Isabel were also among the 2,000 fans who greeted the Red Sox at Boston’s Logan Airport after the Sox had completed their sweep of Oakland. Luis C. and María were the first ones off the chartered plane.60

Luis E. was also at Fenway to see his son win the opener of the World Series, as well as the classic Game Six, which Boston won on Carlton Fisk’s dramatic 12th-inning homer, five innings after Luis C. had come out of the game. However, the older man did not travel to Cincinnati for Game Four, in which his son gutted out a 5-4 complete-game win while throwing 163 pitches.61

After Boston beat Oakland to reach the Fall Classic, Luis E. had said confidently, “We’re going to win it.”62 Yet after Cincinnati came out on top in the dramatic seven-game battle, he said philosophically, “Someone has to win and someone has to lose.”63

The loss to the Reds was bitter, but there was sweetness for the Tiants, as Mark Frost depicted. “The night after Luis’s 6-0 gem in Game One, the Tiants hosted an impromptu gathering for family and friends at their home in [the Boston suburb of] Milton. At around two that morning, as the joyful celebration was winding down, Luis came through a door and saw his father looking up at him from a nearby easy chair, the sweetest, proud, sad smile on his face. He held out his arms, and Luis sat down beside him and they held onto each other, without saying a word, both of them crying silently. The dream, passed down from father to son, had come all the way home.”64

Luis E. and Isabel had come to the U.S. on a three-month visa. They had said they were happy in Cuba and had no intention of staying in the U.S. permanently.65 As it developed, though, they stayed in Massachusetts on extended visas.66 One report said that a special arrangement had been made between the U.S. State Department and Cuba.67 The good offices of Sen. Edward Brooke may well have helped here too.

The three generations of Tiants lived together at Luis C. and María’s home in Milton. Luis C. remembered the times when his parents were with him and watching him play as the best part of his entire career.68 In June 1976, American newspaper readers got to see another warm picture of father and son together as Luis C. was presented with a trophy by the National Father’s Day Committee, which named him “Baseball Father of the Year.” Both were grinning broadly and looking into each other’s eyes; Luis C. had a friendly arm around his father’s shoulders.69

Columnist Milton Richman wrote about this special bond. “I’ll never forget him [Luis E.] standing off to a side underneath the stands at Fenway Park waiting patiently while Luis C. was being mobbed for his autograph after shutting out Cincinnati in the 1975 World Series opener. A special cop, who didn’t know who he was, came up to him and wanted to know why he was standing there waiting. ‘That’s my son,’ explained the elder Tiant, pointing toward Luis C. The cop said ‘He’s a great pitcher.’ Luis Tiant Sr. merely smiled. ‘He’s an even better son,’ he said.”70

In mid-November 1976, Luis E. was admitted to Carney Hospital in Dorchester, just south of Boston. On December 2, the Associated Press reported that he had been undergoing treatment for an unspecified illness for two weeks and that he was in satisfactory condition.71 On Friday, December 10, however, Luis Eleuterio Tiant died of a heart attack.72 Luis C. said that while he and his mother were visiting the hospital, he sat nearby pretending not to listen and heard his father ask Isabel, “I am leaving, are you coming with me or staying?” She responded, “I am coming with you.”73

Two days later, a wake was held for Luis E. at a funeral home in the nearby town of Brookline. After returning from the wake, Isabel was suddenly stricken by a heart attack herself. She was rushed to a hospital but died at 12:30 AM that Monday. It turned out to be a dual wake and funeral Mass, and the Tiants were buried side by side in Milton Cemetery. “I’m grateful to God for allowing my parents to be here and I’m grateful to Him for allowing me the chance to bury them,” said Luis C. “Others like me are not so fortunate because their parents are still in Cuba and can’t get out. Whatever happens is God’s will.”74

The numbers do not reflect Luis E. Tiant’s artistry on the mound. Yet over six decades after his pitching career ended, Sir Skinny’s memory was also honored on film. The touching 2009 documentary The Lost Son of Havana chronicles Luis C. Tiant’s return to Cuba in 2007 after 46 years away, visiting with family members. It opens with a shot of Luis C. puffing on one of his trademark cigars and examining an old black-and-white photo of his father. That relationship is central to the film, which takes the time to explore Luis E.’s life and career. Included is the family reunion in 1975, with a clip of the ceremonial first pitch at Fenway Park that August. There is also rare action footage from the Negro Leagues. Thus it became possible for later generations of fans to catch at least a glimpse of how Lefty Tiant tantalized hitters.

Acknowledgements

Grateful acknowledgment to Luis Clemente Tiant for providing personal memories of his parents, and to SABR member José Ignacio Ramírez, who conducted an in-person interview with Tiant at the Ramírez home on September 7, 2014. Continued thanks to Rubén Amaro Sr. for his memories and Jorge Figueredo for his contribution of Cuban statistics.

Photo credits

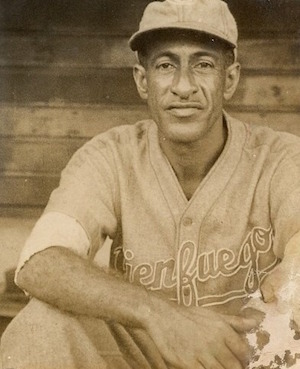

With Cienfuegos, probably circa 1945 to 1947: Courtesy of César Brioso collection (cubanbeisbol.com)

At Fenway Park, August 26, 1975: Courtesy of the Boston Red Sox.

Sources

Books

Burgos, Jr., Adrián, Cuban Star. New York: Hill and Wang, 2011.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball, 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003.

Figueredo, Jorge S. Cuban Baseball: A Statistical History 1878-1961. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2003.

Frost, Mark. Game Six: Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America’s Pastime, New York, New York: Hyperion, 2009.

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana, New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Lester, Larry. Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001.

Tiant, Luis and Joe Fitzgerald. El Tiante, New York, New York: Doubleday, 1976.

Torres, Ángel. La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997, Miami, FL: Review Printers, 1996.

Treto Cisneros, Pedr.o ed., Enciclopedia del Béisbol Mexicano, Mexico City: Revistas Deportivas, S.A. de C.V., 11th edition, 2011.

Films

The Lost Son of Havana, written and directed by Jonathan Hock, ESPN Films, 2009.

Internet resources

Armour, Mark. “Luis Tiant,” SABR BioProject

www.baseball-reference.com

www.retrosheet.org

www.paperofrecord.com (The Sporting News online)

Notes

1 Bruce Lowitt, “Tiant Proving Johnson Right About Last Look,” Associated Press, August 6, 1974.

2 “Tiant, Parents, Reunited; Sox Host ChiSox Tonight,” United Press International, August 22, 1975.

3 Thomas Boswell, “Tiant Sees World As Both Funny, Sad,” Gannett News Service, October 10, 1975.

4 Nick Wilson, Early Latino Ballplayers in the United States, Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005: 125.

5 Luis Tiant and Joe Fitzgerald, El Tiante, New York, New York: Doubleday, 1976.

6 Larry Lester, Black Baseball’s National Showcase: The East-West All-Star Game, 1933-1953, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2001: 64. In 1966 , Bert Campaneris said that after Whitey Ford, Luis C. had the best pickoff move in the American League. Milton Richman, “Today’s Sports Parade,” United Press International, April 21, 1966.

7 Roberto González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 1999, 261.

8 Gary Gillette, Pete Palmer, Stuart Shea, eds., The ESPN Pro Baseball Encyclopedia, New York, New York: Sterling Publishing Co., 2007: 1699.

9 Regis McAuley, “Tiant, Overlooked in 1963 Draft, Is Now Toast of Tepee,” The Sporting News, August 1, 1964, 9.

10 Dan Donovan, “Negro Leagues Reunion Stirs Fun Flashbacks,” Pittsburgh Press, July 1, 1981, C-1.

11 According to José Ramírez, “When I interviewed [Luis C.] Tiant, he did not seem to recollect some of the names of that generation or preferred not to talk much about it. I could never be sure.”

12 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014. Since Luis Eleuterio Tiant’s father was also named Luis, this biography avoids the use of Sr. and Jr. when discussing the two pitchers, except for quotations. It is also worth noting that in Hispanic culture, people are often referred to by both of their given names.

13 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

14 Alan J. Pollock, Barnstorming to Heaven: Syd Pollock and His Great Black Teams, Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2006, 73.

15 “Cubans Annex Memphis Series,” The Afro-American, April 30, 1932, 14.

16 Syd Pollock, “League Started in Wrong Year, Owner of Cuban Stars Believes,” The Afro-American, July 9, 1932, 14.

17 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 163.

18 Alan J. Pollock, Barnstorming to Heaven, 74.

19 Lester, 64.

20 Ibid., 78.

21 Ibid., 64.

22 Ibid., 64.

23 “Havana Nine Wins Ocer Cardinals,” Associated Press, March 6, 1936.

24 William F. McNeil, Black Baseball Out of Season, Jefferson City, NC: McFarland & Co., 2007: 144, 217.

25 E-mail from Rubén Amaro Sr. to Rory Costello, August 18, 2014 (cited with permission).

26 “Cuban Stars Face Parkways Sunday,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 19, 1939, 16.

27 Randy Dixon, “15,000 See Four Team Twin Bill in Yankee Stadium,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 10, 1939, 16.

28 Lester, 285, 294, 302.

29 Lou Hernández, Memories of Winter Ball, Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2007: 209.

30 Brent Kelley, Voices from the Negro Leagues, Jefferson City, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 1998: 59.

31 Adrián Burgos, Jr., Cuban Star, New York: Hill and Wang, 2011, 175-176.

32 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

33 González Echevarría, The Pride of Havana, 261.

34 Jorge Alarcón, “Mexican Rosters Shapen Up after Loop’s Shrinkage,” The Sporting News, August 11, 1948, 36.

35 Jorge Alarcón, “Mexican League Players Shift to Yucatan’s Loop,” The Sporting News, October 6, 1948, 40.

36 Boswell, “Tiant Sees World As Both Funny, Sad”

37 Mark Frost, Game Six: Cincinnati, Boston, and the 1975 World Series: The Triumph of America’s Pastime, New York, New York: Hyperion, 2009.

38 Russell Schneider, “Dad Writes Often to Luis, Tells Him to Keep Skinny,” The Sporting News, May 28, 1966, 6. “Elder Tiant Joins Fun with Red Sox, Angels,” Associated Press, August 27, 1975.

39 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

40 “Tiant Real Worrier,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1967, 47.

41 Mark Armour, “Luis Tiant,” SABR BioProject. Drawn from Tiant and Fitzgerald, El Tiante.

42 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

43 Armour, “Luis Tiant”. Date of Fitzgerald’s original article is uncertain.

44 Frost, Game Six. Ángel Torres, La Leyenda del Béisbol Cubano, 1878-1997, Miami, Florida: Review Printers, 1996, 247.

45 An Associated Press report from May 9, 1975 stated that Luis E. and Isabel were living 350 miles away from Havana at that time, but Luis C. refuted this assertion in 2014.

46 “McGovern flies to Cuba,” Associated Press, May 6, 1975.

47 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

48 Edward W. Brooke, Bridging the Divide: My Life, Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006.

49 Various contemporary stories noted Brooke’s involvement, but the direct quote from the letter may be found in Frost, Game Six.

50 O’Hara, “Luis Tiant to have reunion with parents”.

51 Frost, Game Six.

52 “Elder Tiant Joins Fun with Red Sox, Angels”.

53 Frost, Game Six.

54 “Luis Tiant Sr. returns to mound,” Associated Press, August 27, 1975.

55 “Elder Tiant Joins Fun with Red Sox, Angels”.

56 Peter Gammons, “Red Sox’ Lee – Showman and a Super Pitcher,” The Sporting News, September 13, 1975, 11.

57 “Luis Tiant Sr. returns to mound”.

58 Boswell, “Tiant Sees World As Both Funny, Sad”.

59 Peter Gammons, “Luis Tiant leads Red Sox past A’s in Game 1,” Boston Globe, October 5, 1975.

60 “Sox, Reds arrive home with flags,” Associated Press, October 8, 1975.

61 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

62 “Sox Fans Line Up,” United Press International, October 9, 1975.

63 “World Series Quotes,” Sarasota Journal, October 23, 1975, 6-D.

64 Frost, Game Six

65 “Tiant, Parents, Reunited; Sox Host ChiSox Tonight”.

66 “Tiants’ Funeral Set Today,” United Press International, December 14, 1976.

67 “People making the news,” Associated Press, December 2, 1976.

68 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

69 “Dad’s proud dad,” United Press International, June 10, 1976.

70 Milton Richman, “Tiant’s loss is felt by everyone,” United Press International, December 15, 1976.

71 “People making the news”.

72 Richman, “Tiant’s loss is felt by everyone”.

73 In-person interview, José I. Ramírez with Luis Clemente Tiant, September 7, 2014.

74 “Tiants’ Funeral Set Today”. Their resting place is noted in “Funeral conducted for Tiant’s parents,” Associated Press, December 15, 1976.

Full Name

Luis Eleuterio Tiant Bravo

Born

August 27, 1906 at La Habana, La Habana (CU)

Died

December 10, 1976 at Milton, MA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.