Mike Sandlock

When Mike Sandlock signed his first professional baseball contract, in 1938, he could not have envisioned that he would become a major-league teammate of no fewer than six Hall of Famers – Warren Spahn, Paul Waner, Ernie Lombardi, Pee Wee Reese, Billy Herman, and Ralph Kiner. Nor could he have imagined that during his five full or partial seasons in the National League, Hall of Famers Casey Stengel and Leo Durocher would be among his managers.

When Mike Sandlock signed his first professional baseball contract, in 1938, he could not have envisioned that he would become a major-league teammate of no fewer than six Hall of Famers – Warren Spahn, Paul Waner, Ernie Lombardi, Pee Wee Reese, Billy Herman, and Ralph Kiner. Nor could he have imagined that during his five full or partial seasons in the National League, Hall of Famers Casey Stengel and Leo Durocher would be among his managers.

In 2015 Michael Joseph Sandlock held yet another distinction: He was the oldest living former major leaguer. This son of Polish immigrants, Stanley and Catherine Sandlock, marked his 100th birthday on October 17, 2015.

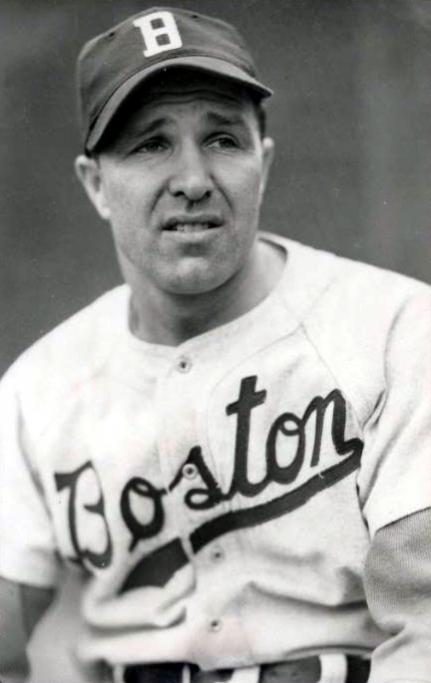

For 16 summers, many of them glorious, the Old Greenwich, Connecticut, native earned his livelihood in major- and minor-league ballparks. He was a 6-foot-1 switch-hitting infielder and catcher who possessed enough talent and grit to play for three NL clubs, the Boston Braves, Brooklyn Dodgers, and Pittsburgh Pirates. He played at the game’s next highest level, Triple A, for eight seasons, at San Diego, Hollywood, Montreal, and St. Paul. (All of those cities became part of the major-league landscape.)1

Sandlock wasn’t a star at the major-league level, but he played with many who were. He and Spahn were teammates with Evansville of the Three-I League in 1941; both were called up to Boston in September of 1942. Stengel was the manager of this seventh-place club, Lombardi, the regular catcher, was en route to winning his second batting title, and Waner played the outfield.

“That was the best drinking club I ever ran into,” Sandlock said of the 1942 Braves. He didn’t name names, but it’s well known that Stengel – still several years removed from being anointed a managerial genius with the New York Yankees – and Waner were on friendly terms with the bottle.

When Sandlock made his NL debut with the Braves on September 19, 1942, the news from most World War II fronts was alarming. The Russians were fighting for their very lives against the Nazis at Stalingrad. In the Pacific, US Marines were attempting to hold the Guadalcanal airfield in the Solomon Islands against repeated attacks by the Japanese. On another ominous note, Pope Pius XII granted an audience to President Roosevelt’s personal representative to the Vatican; they reportedly discussed anti-Semitic developments in Vichy France.

The crowd at Braves Field in Boston was sparse that afternoon when Stengel sent Sandlock to pinch-hit for shortstop Whitey Wietelmann in the eighth inning against New York Giants reliever Fiddler Bill McGee. Sandlock promptly lined a single up the middle and eventually scored on Clyde Kluttz’s two-run triple. Mel Ott’s bases-filled home run one inning earlier, though, put the game in the Giants’ win column, 7-6.2

Sandlock encountered Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson when the Dodgers went to Havana for spring training in 1947. Both were members of Brooklyn’s top farm club, the Montreal Royals of the International League; Jackie would eradicate baseball’s color line when he was promoted to the parent Dodgers just before the season.

Like most of the players in camp, Sandlock refused to sign the short-lived petition that opposed Jackie joining the Dodgers. “(Dodgers president) Branch Rickey called me into his office and asked if I would play pepper with Jackie,” Sandlock related. “‘Why not?’ I said.

“To me, Jackie was a great player, period. And a hell of a good golfer, too. After he moved up to Stamford we played golf together a couple of times.”

During the 1947 International League season, Sandlock formed a bond with Montreal teammate Roy Campanella, the future Hall of Fame catcher who won three Most Valuable Player awards and played a key role in five Dodgers pennants. “The nicest little chap, very friendly,” he said of Campy.

In his 2011 book Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella, author Neil Lanctot underscored their friendship: “We used to walk the streets and everything and talk baseball,” Sandlock remembered. “He was very easy to get along with … not hard to explain things to.”3

According to a 1950 article in Ebony magazine, Campanella attributed much of his defensive success “to a lesson he learned in 1947 from a white teammate, Mike Sandlock.” The latter “‘had spotted my windmill throwing motion and went to work on me. I learned to get the ball off quickly and without a windup.’ That’s when I started to nail some of those fast fellows.”

In 1948, Sandlock’s Montreal teammates included future Hall of Famer Duke Snider, hard-throwing right-hander Don Newcombe, and a lanky first baseman named Chuck Connors. “Moody,” he said of Snider, the talented power-hitter and center fielder who led Brooklyn to five NL pennants in an eight-year span. “Newcombe, he threw hard and heavy. My hand used to puff up after catching him.”

The 6-foot-5 Connors reached the majors briefly with the Dodgers and Chicago Cubs, but rose to prominence later in the title role of television’s The Rifleman and as a featured player in The Big Country and other films.

It was Connors who encouraged Sandlock to join him playing ball in Cuba during the winter of 1948-49. Their team, Almendares, won the championship, and among the notables on the squad were Monte Irvin, Sam Jethroe, Al Gionfriddo (he of the memorable catch of Joe DiMaggio’s wallop in the 1947 World Series), Connie Marrero, and manager Fermin “Mickey” Guerra. The batboy in the team photo is Sandlock’s 5-year-old son, Mike.4

Marrero, a pitching legend in his native Cuba and an All-Star with the 1951 Washington Senators, died just two days shy of his 103rd birthday on April 23, 2014. His passing made Sandlock the oldest living former major leaguer.

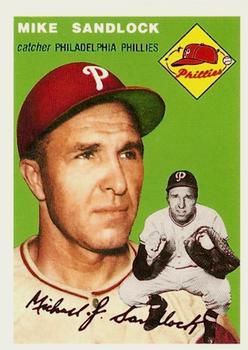

When Sandlock returned to the majors at age 37 with Pittsburgh in 1953, Kiner, the seven-time home-run champion, still wore Pirate flannels. Their friendship would endure until Kiner’s death in 2014. Joe Garagiola, the catcher turned broadcaster and raconteur, was there, too. And so was another Greenwich native, infielder Pete Castiglione. All three were traded in midseason, and Sandlock was dealt to the Phillies that December.

Sandlock grew up in the Old Greenwich section – then known as Sound Beach – of Greenwich, a Fairfield County community called home by millionaire bankers and billionaire hedge-fund managers, where such notables as Ron Howard, Diana Ross, Frank Gifford, Steve Young, former Baseball Commissioner Fay Vincent, Tom Seaver, and Mark Teixeira reside or once lived.

“This used to be a dirt road,” he said, gesturing toward Rockland Place, the same street on which he grew to manhood during the Depression. “There used to be cattle next door, haystacks over there.”

His formal education was limited to Sound Beach School and a couple of years at Wright Tech in neighboring Stamford. That was it. Then he was off to work at the Electrolux plant and play industrial league ball with the Cos Cob Fire Department and other teams. In 1937 he impressed Boston Bees scouts during a tryout, and they signed him to a professional contract.

“I was making $200 a month at Electrolux. My first year I got $75 a month to play at Huntington, West Virginia, in the Mountain State League,” he recalls. “My father used to say working in a factory is like going to jail. They open the gate in the morning and they don’t let you out until it’s time to quit.”

Sandlock’s rise through the Bees/Braves farm system was rapid. He hit a sound .276 at Huntington in 1938, an even .300 with Bradford, Pennsylvania, the following year, where he was voted the Pony League’s all-star catcher. He was relegated to backup duty with Hartford of the Eastern League in 1940, but rebounded with .324 and .306 seasons at Evansville of the Three-I League, which earned him the late-season promotion to Boston in 1942. He played in two games at shortstop with the ’42 Braves, finishing with that one hit and one at-bat, which translated into a 1.000 batting average.

With the war escalating, Sandlock sat out the 1943 season and worked in a plant in Evansville, Indiana, that built fighter planes. That winter the love of his life, Victoria (Suchocki) Sandlock, gave birth to Michael, the oldest of their three children.

He rejoined the Braves for 30 games and a .100 batting average in the first half of the 1944 season, before his contract was sold to the Dodgers. He hit .308 in 35 games with St. Paul of the American Association, setting the stage for his finest National League season.

With a third-place Brooklyn club in 1945, Sandlock appeared in 80 games – 47 behind the plate but he also played third, short, and second – and batted a solid .282, with 2 home runs and 17 RBIs.

Manager Leo Durocher “really wanted to win. To me, he was a fine manager,” Sandlock said. “His wife, (actress) Laraine Day, was a very nice person. She’d play cards with you.”

As the Dodgers’ Opening Day shortstop, against the Philadelphia Phillies on April 17, Sandlock enjoyed one of his most productive days, going 3-for-4 with a triple and driving in three runs. Durocher played second base that afternoon. The Dodgers won handily, 8-2.5

Both of Sandlock’s major-league homers came that year, against the same Giants right-hander, Harry Feldman. “My first home run was in the Polo Grounds (on April 20). The second hit the clock at Ebbets Field (on September 19).” The latter, with two runners aboard, propelled the Dodgers to a 3-0 lead in a game they eventually won, 5-4.

To reach Ebbets Field from Old Greenwich, Sandlock rode the New Haven Railroad to Manhattan, and then boarded a subway to Brooklyn. He recalled walking to the ballpark and signing autographs for youngsters along the way. He remembered Ebbets Field as a “cozy park,” where the ushers always greeted him with a “Hey, Mike!” and members of the Dodgers Sym-Phony band sometimes supplied him with sandwiches between games of doubleheaders.6

Of Brooklyn fans, he said, “They boo you one minute and then cheer for you the next. ‘You’re bums, but you’re our bums,’ they used to say,” Sandlock told Ed Attanasio in the online feature “They Were There.” “I got to know some of them, including Hilda (Chester) with the cowbell. She was quite a character. The fans were really close to the players and people would yell out stuff that was funny and witty.”7

On his circuitous trip home after games, Sandlock occasionally met Red Barber, the Dodgers’ announcer, for a beer at Grand Central Terminal. Barber hung a nickname on Mike: “The Old Commuter.”

The Dodgers found themselves in third place at season’s end, behind the Cubs and St. Louis Cardinals, but there was more baseball to be played. That December Sandlock was among a team of major leaguers who made a USO-sponsored tour across the US, playing service teams, and then moving on to Hawaii and the Philippines. They returned home exhausted but happy at the end of January.

“Some of the flights were pretty scary,” he remembered. “We played Stan Musial’s (Navy) team in Hawaii and we ran into (Dodger pitcher) Kirby Higbe in the Philippines.” Another Dodger, Ralph Branca, Frank McCormick, Whitey Kurowski, and Red Barrett were among Sandlock’s notable teammates.

With the war over and a flock of stars returning from military service, major-league rosters were overstocked in the spring of 1946. Shortstop Pee Wee Reese, who spent three years in the Navy, center fielder Pete Reiser, second baseman Billy Herman and third baseman Cookie Lavagetto were among the returnees from the Dodgers’ 1941 NL champions.

A split right forefinger, incurred in a spring-training victory over the Giants, delayed Sandlock’s arrival.8 He spent the first portion of the season with Brooklyn, hitting just .147 in 19 games, before being reassigned to St. Paul. He was destined to spend the reminder of his playing career at the Triple-A or Open level, save for the season in Pittsburgh.

No complaints, though. “The best time I had (in the game) was out on the Coast,” he said. “Some of the teams in the Pacific Coast League were better than some of the National League teams at the time.”

No question. Many stars on the way down – Joe Gordon, Luke Easter, Max West, Walt Judnich – were quite content to finish up in the PCL. Johnny Lindell, the former Yankee outfielder, spent two seasons perfecting a knuckleball with Hollywood, and both he and Sandlock accompanied manager Fred Haney to Pittsburgh in 1953.

No question. Many stars on the way down – Joe Gordon, Luke Easter, Max West, Walt Judnich – were quite content to finish up in the PCL. Johnny Lindell, the former Yankee outfielder, spent two seasons perfecting a knuckleball with Hollywood, and both he and Sandlock accompanied manager Fred Haney to Pittsburgh in 1953.

God’s sunlight always seemed to shine on Hollywood. And the money was good, too. “I was making ten grand a year out there,” Sandlock said.

For four seasons (1949-52), Sandlock was Hollywood’s regular catcher, a period in which the Stars (as they were appropriately known) won two PCL championships and attracted crowds that taxed the capacity of Gilmore Field. Show-business personalities of the day – George Burns and Gracie Allen, Jack Benny, Phil Silvers, Mickey Rooney, Pat O’Brien, Gordon MacRae, Chill Wills, Gabby Hayes – populated the stands to see and be seen. Gene Autry, the singing cowboy, and William Frawley, who portrayed Fred Mertz on I Love Lucy, were among the club’s investors.9

Sandlock’s son, Mike, recalled accompanying his father to the home of actors Michael O’Shea and Virginia Mayo and meeting other celebrities.

The Stars captured PCL championships in 1949 and 1952, and finished no lower than third in the seasons in between. Sandlock complemented his defensive skills as a backstop with a .297 average in 1950 and hit .286 in the playoff-winning 1952 season. He batted .243 in 1949 and .248 in 1951.

Included in the voluminous collection of Sandlock memorabilia is a black-and-white photograph of Joe DiMaggio swinging a bat, taken during an exhibition game on the West Coast in the fall of 1951 – the year Joe D retired. “That was Joe’s last (albeit unofficial) at-bat,” Sandlock said. In the photo, the catcher behind the plate is Mike Sandlock.

By this juncture, Sandlock had become known as a player who could catch the knuckleball – most of the time. “You don’t (catch it),” he said. “You box with it. You use either a left jab or a hook. … I had special gloves made. You can’t use a regular catcher’s glove, because you don’t let the ball slam into the pocket, the way you do catching a fastball pitcher.”10

Life was decidedly less glamorous in Pittsburgh. The 1953 Pirates, a mixture of graybeards and kids, won just 50 games and finished last in the eight-team National League. Sharing the catching with Garagiola, rookie Vic Janowicz, who had been a Heisman Trophy-winning running back at Ohio State, and Toby Atwell, Sandlock batted .231 in 64 games. Defensively, he handled the knuckleballs thrown by Lindell and Paul LaPalme and committed just three errors for a .991 percentage. He ranked fifth among NL catchers with 49 assists.

In the 2013 SABR publication Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees, Lindell gives considerable credit to Sandlock for his comeback as a pitcher. Wrote author Rob Neyer:

“ ‘He helped me greatly,’ ” Lindell said of Sandlock. ‘It was he who nursed me along, gave me encouragement and acted as my tutor and counselor. My luckiest break, next to coming back to the big leagues, was when Haney and Sandlock were brought up to the Pirates with me.’ ”11

For Sandlock, the highlight of the summer was Mike Sandlock Day at the Polo

Grounds, held between games of a September doubleheader. (The Pirates actually won both.) A group of fans from Greenwich and Stamford presented him a new Dodge and other gifts during brief ceremonies while his wife and their two children, Mike and Mary Ellen, beamed. Their third child, Damon, was born a few years later.

Sold to the Phillies during the offseason, Sandlock appeared to have won a roster spot on the 1954 club managed by Steve O’Neill. That plan was thwarted by a severe knee injury sustained in the waning days of spring training. “We were playing an exhibition game in Schenectady (New York) and this young kid came barreling into me at the plate,” Sandlock said. “He was out from here to Broadway, but …”

A major “but.” The next uniform he wore was that of San Diego, where a 38-year-old Sandlock helped manager Lefty O’Doul’s Padres win the PCL title in a one-game playoff with Hollywood. He hit only .183, but caught with his customary expertise.

“Baseball has done a great deal for me,” Sandlock told Les Biederman of the Pittsburgh Press. “It’s enabled me to make a living. I have never been a great player but nobody can say I never have given my best at all times.”12

Sandlock retired from baseball after that season (major-league statistics: 195 games, 107 hits, 2 home runs, 31 RBIs, .240 average) and, as he had in most offseasons, continued to work as a carpenter. According to son Mike, “he worked as a builder (mostly additions) with Joe Valentine, and was able to determine the best playing position for his young son Bobby Valentine.”

Sandlock also developed into a two-handicap golfer at the local Innis Arden Golf Club, where he won five club championships and carded two holes-in-one. In 2009, at 93 and limiting himself to two rounds of golf a week, he was honored at the annual Jerry Porricelli Sr. Memorial Golf Tournament at the club. Among those in attendance was Ralph Kiner.

“Mike is an old teammate of mine from the Pirates and it is a pleasure to be here for him on this day,” Kiner said. “I had a lot of fun playing with him … even though we didn’t have a great team.”13

Two other events, both baseball-related, probably resonated deeper in the Sandlock psyche. On April 30, 1998, Sandlock was inducted into the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame, permanently reuniting him with Newcombe, Branca, Tommy Brown, and several other teammates. He recalled a chance meeting with Newcombe, when the 1956 Cy Young Award and MVP winner “gave me the biggest hug when I saw him at a card show on Long Island.”

On July 21, 2012, Sandlock was honored as the oldest living Dodger at the New York Mets’ Citi Field before their game with the Los Angeles Dodgers. Wearing a blue Brooklyn Dodgers cap, he navigated the field by cane, and was introduced to Dodgers manager Don Mattingly and several players from both clubs. He also reconnected with the Mets’ third-base coach, fellow Greenwich native Tim Teufel.14

The modern game irks him, Sandlock said. “Bunt, hit and run – they don’t do that anymore,” he said with a groan. “Everything is the long ball. I mean, a guy on first and second, jeez, bunt that guy to third. Get that one run if you can.”15

In his later years, Sandlock resided with his youngest son, Damon, Damon’s wife, Allie, and their two children in the Cos Cob section of Greenwich. His oldest son, Mike, lived in Tennessee; there were six Sandlock grandchildren. Sandlock’s wife, Vicki, who compiled the scrapbooks of his memorabilia, died in 1982.

On the verge of being a centurion, how did the former major leaguer spend his days? “He gets to Innis Arden once a week on weekends, and watches golf and baseball on television. He sits outside reading the paper on beautiful days,” said Allie Sandlock.

Sandlock’s low-key approach to life and longevity? “Win some, walk off. Go in, have a beer. That’s it.”16

Postscript

Sandlock died after a battle with bone cancer on Monday, April 4, 2016, nearly six months after celebrating his 100th birthday.

Sources besides those cited in notes

Special thanks to Mike Sandlock for a follow-up interview on July 15, 2015; to Sandlock’s two sons, Mike and Damon Sandlock, for sharing their memories with the author on June 15, 2015, and July 8, 2015, respectively; and to daughter-in-law Allie Sandlock for her assistance on July 14, 2015.

“Phils Purchase Sandlock From Pittsburgh Club,” publication unknown, December 20, 1953.

Notes

1 Don Harrison, “Old Greenwich’s Gift to Majors,” Greenwich (Connecticut) Citizen, July 18, 2003.

2 James P. Dawson, “Ott’s Home Run With Bases Filled Conquers Braves for Giants, 7-6,” New York Times, September 20, 1942.”

3 Neil Lanctot, Campy: The Two Lives of Roy Campanella (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2011).

4 Cesar Brioso, “Friendship With Chuck Connors Helped Mike Sandlock Land in Cuba One Winter,” Cuba Beisbol, January 26, 2011.

5 Jack Smith, “Sandlock Ousts Brown as Dodger Shortstop,” New York Daily News, April 10, 1945.

6 Louie Lazar, “At 97, the Oldest Living Brooklyn Dodger Reflects,” New York Times, April 3, 2013.

7 Ed Attanasio, “They Were There: Mike Sandlock,” “This Great Game,” 2015.

8 Gus Steiger, “Hatten Beats Giants; Sandlock Splits Digit,” New York Daily Mirror, April 3, 1946.

9 Jeff Hause, “Hollywood Stars: A History,” SportsHollywood.com, 2003.

10 Frank Yeutter, “Phils’ Sandlock Uses Special Catcher’s Mitt, Stands a Step Farther Back for ‘Knucklers,’” The (Philadelphia) Sunday Bulletin, February 28, 1954.

11 Rob Neyer, “Johnny Lindell,” in Lyle Spatz, ed., Bridging Two Dynasties: The 1947 New York Yankees (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2013), 165.

12 Les Biederman, “The Scoreboard,” Pittsburgh Press, March 25, 1953.

13 Rob Kelley, “Sandlock: Former Major League Baseball Player Honored at Celebrity Golf Tournament,” Greenwich (Connecticut) Citizen, August 14, 2009.

14 Scott Ericson, “Sandlock honored at Citi Field,” Greenwich (Connecticut) Time, July 21, 2012.

15 Jack Cavanaugh, “Oldest Living ex-Dodger Will Meet the Current Team in New York,” Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2012.

16 Lazar.

Full Name

Michael Joseph Sandlock

Born

October 17, 1915 at Old Greenwich, CT (USA)

Died

April 4, 2016 at Cos Cob, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.