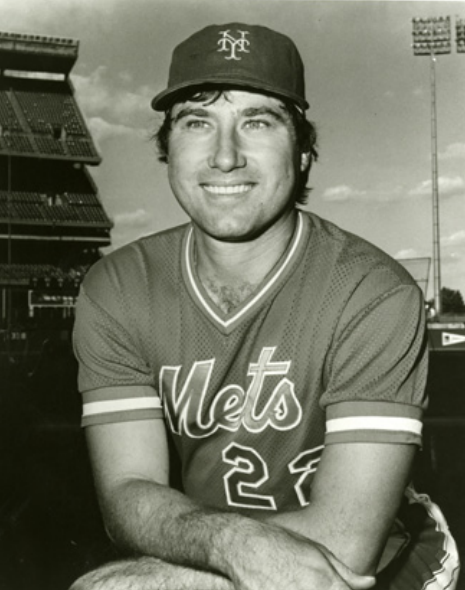

Ray Knight

By the time Ray Knight leapt down the third-base line on the night of October 25, 1986, landing on home plate and forever cementing his legacy in New York baseball history, he was already an 11-year veteran. He had seen much in his professional career, including a trip to the postseason in 1979, but he had never seen anything like the events that led to his scoring the winning run in one of the most dramatic games in baseball history. Few had. But there was even more magic to come two nights later. A completely unexpected turn of events, orchestrated in a New York minute by a country boy from Albany, Georgia, sealed the fate of the Boston Red Sox and allowed the New York Mets to hoist the second world championship banner in their history.

By the time Ray Knight leapt down the third-base line on the night of October 25, 1986, landing on home plate and forever cementing his legacy in New York baseball history, he was already an 11-year veteran. He had seen much in his professional career, including a trip to the postseason in 1979, but he had never seen anything like the events that led to his scoring the winning run in one of the most dramatic games in baseball history. Few had. But there was even more magic to come two nights later. A completely unexpected turn of events, orchestrated in a New York minute by a country boy from Albany, Georgia, sealed the fate of the Boston Red Sox and allowed the New York Mets to hoist the second world championship banner in their history.

Knight’s beginnings were the humble stuff of a typical baseball rags-to-riches tale. He was born on December 28, 1952, in Albany, Georgia. His father worked for the city parks department.1 Ray attended Dougherty High School (also the alma mater of one other major leaguer, Gene Martin, who played in nine games with the Washington Senators in 1968). Ray made a name for himself in high school as a ballplayer and boxer. A fighter at heart, he became a Golden Gloves boxer in addition to World Series hero.

Knight’s high-school performance on the diamond was impressive enough for the Cincinnati Reds to select him in the 10th round of the 1970 draft. The next summer, after graduation, Knight was in Sioux Falls, playing for the Reds’ affiliate in the Class-A Northern League. Uncertain where to play the versatile athlete, the Packers had Knight play every position except catcher, even pitching in three games. His primary positions were in the outfield and at shortstop. Batting .285 with six home runs in 64 games, the promising youth was promoted to Double-A Trois-Rivieres (Eastern League) for 1972.

That was a more challenging year for Knight; his average dipped to a weak .212 and he hit only two home runs. Knight would never be known as a power threat, but his .265 slugging percentage, 20 points lower than his previous season’s batting average, was troubling. The Reds kept him in Trois Rivieres for the start of the 1973 season, and he rebounded enough (.280 in 57 games) to earn his way to the Triple-A Indianapolis Indians in midseason.

Knight struggled again, and was hitting a poor .227 in 1974 when he got an unexpected September call-up. Knight’s major-league debut came on September 10, when he was inserted at third base in the sixth inning of a game against the San Diego Padres. He struck out in his lone at-bat, and fared little better throughout the month, going 2-for-11 in 14 games. He got his first major-league hit, a two-run double, in a September 28 blowout of the San Francisco Giants.

It took two more full seasons before Knight returned to the majors. He spent 1975 and 1976 in Indianapolis, becoming a more reliable hitter and watching from afar as the Reds won the World Series in those two seasons.

Promoted to the Reds in 1977, Knight would never play in another minor-league contest. He played in half of the team’s games in ’77, mostly as a pinch-hitter, and batted .261 in 103 plate appearances as the Reds finished 10 games behind the eventual National League champion Los Angeles Dodgers.

The next season was a disappointment for Knight. His batting average fell to .200. The Reds finished just 2½ games behind the Dodgers, but the future of the team and Knight’s role were in doubt by season’s end. Knight was firmly ensconced as a backup third baseman, the realm of Reds superstar Pete Rose.

Rose, however, moved to the Philadelphia Phillies as a free agent for the 1979 season, and the Reds’ third-base job fell the still unreliable Knight. But Ray surprised by batting .318 and slugging .454, both career highs. He finished fifth in MVP voting and his emergence played no small part in the Reds’ return to the postseason, though they did not go far, being swept in three games by Pittsburgh in the National League Championship Series. Knight batted .286 in what was his lone postseason appearance with Cincinnati.

Knight continued to shine at the start of 1980, making his first appearance in the All-Star Game. He went 1-for-1 in the game, with a walk and an unlikely stolen base (Knight had only 14 for his career). He entered the game in the sixth inning and scored the tying run, helping the National League go on to win 4-2. But from that point Knight’s season began to slip downhill. Entering the All-Star Game he was batting a respectable .289, but after the break his average slipped to .264 by season’s end, and he led the league in grounding into double plays.

Knight’s statistics in the strike-shortened season of 1981 were similar to 1980’s, with a slightly higher on-base percentage and a slightly lower slugging percentage. It was another disappointing season for the Reds. Afterward they lost outfielders Ken Griffey to a trade with the Yankees and Dave Collins to free agency. In an attempt to shore up their outfield, the fan favorite Knight was traded to Houston for César Cedeño.2 In a strange twist of baseball fate, Knight (who was known as a fighter throughout his playing career) and Cedeño had participated in an on-field brawl on the Fourth of July in 1979 after Knight challenged the entire Astros bench to fisticuffs.3

The same year Knight was traded, he divorced his first wife, Terri Schmidt. The trade to Houston put him in closer contact with future Hall of Fame professional golfer Nancy Lopez, whom he had met and previously befriended in 1978 when they were both playing in Japan. Recently divorced herself, Lopez and Knight grew even closer and ultimately became lovers. In 1982 they married, becoming one of sport’s higher profile couples.4

Perhaps it was the rejuvenation of his love life, or perhaps it was inspiration born of a Southern boy returning below the Mason-Dixon line, but Knight’s first season in Houston was a rebirth. In 1982 he batted .294, leading all other regulars by over 15 points on a weak Astros squad that finished in fifth place, ahead of only the truly woeful Reds in the NL West. Knight made his second All-Star Game appearance, and once again figured in MVP voting. Knight and the Astros seemed to be a match made in heaven.

The happy marriage continued in 1983 when Knight hit over .300 for the second and final time in his career. Knight, who had begun to transition to first base with the trade to Houston, played the entire 1983 season at that position.

Knight split time between the two corners in 1984. Plagued by persistent pain in his right shoulder, he saw his numbers fall sharply. By late August he was batting only .223 in 88 games. That was when the Mets, who had been looking for a consistent third baseman seemingly since their inception in 1962, came calling. Knight was dealt to the Mets for three players.

When Knight arrived in New York on August 28, 1984, it was the beginning of a period of transition for the historically woeful Mets, whose last postseason appearance had been a World Series loss to the Oakland A’s in 1973. They had acquired first baseman Keith Hernandez the year before, slugger Darryl Strawberry was proving that he was not a one-year fluke and phenom Dwight Gooden was en route to the Rookie of the Year award. With the addition of future Hall of Fame catcher Gary Carter during the offseason, Knight had become a part of a team with tremendous promise.

During the offseason Knight underwent orthoscopic surgery on his nagging shoulder and the Mets, concerned that he would not be 100 percent for 1985, traded Walt Terrell to the Detroit Tigers for Howard Johnson in December.5 The Mets’ concerns seemed justified in 1986 as Knight hit a paltry .218, the lowest full-season average in his career to that point. Johnson fared only a little better, batting .242. Entering the 1986 season, the hot corner in Flushing still seemed to be a question mark.

That question did little to deter the Mets however, as they started winning right out of the gate. They were 13-3 and five games up at the end of April, including an 11-game winning streak. Knight was batting .306 with six home runs in the first month of the season and Johnson found himself relegated to a part-time role.

Knight was a perfect fit for the rowdy Mets, known for their wild (some say arrogant) antics on and off the field, Of his many on-field altercations, perhaps the most famous was a brawl on July 22 with the Reds’ Eric Davis. After Davis came in hard on a slide into third, Knight started barking at the athletic outfielder. Davis gave Knight a shove, and that was when the Golden Gloves boxer slugged the Reds outfielder in the jaw. The benches cleared and, by the time it was over, so many players were either injured or ejected that Gary Carter was playing third and relievers Jesse Orosco and Roger McDowell alternated between pitching duties and playing the outfield.

The Mets dominated the NL East throughout the season and finished with a record of 108-54, leading the second-place Phillies by 21½ games. Knight had an opportunity to exact a measure of vengeance on his former employers, the Houston Astros, in the Championship Series, but mostly failed to live up to the chance. With Knight batting only .167 in 26 plate appearances, it was Strawberry who provided the offensive heroics throughout the series. Knight did have the final say, however, in the 16-inning war that was the deciding Game Six. He knocked in two runs, including the go-ahead run, in the 16th.

It was be the World Series, against the snake-bitten Red Sox, in which Knight put on an offensive show previously unseen in his career. He batted .391, knocking in five runs and scoring four, including the iconic winning run in Game Six as Mookie Wilson’s slow grounder dribbled through the legs of the hobbled Bill Buckner.

That moment has become so famous in Mets lore that it is often forgotten that Knight’s best game of the Series may have been the final one. With the game knotted at 3-3 in the seventh, Knight led off the inning against Calvin Schiraldi with a home run that put the Mets ahead for good. After a base hit in the eighth, making him 3-for-4, Knight scored the Mets’ final run of 1986 when pitcher Jesse Orosco knocked a single to center field, making the score 8-5, the score of the game that secured the Mets their second world championship. Knight was named the World Series MVP as well as the National League Comeback Player of the Year by The Sporting News.

It was with some surprise, then, that on November 12, just two weeks after Knight was the toast of the city, that the Mets granted him free agency after Knight refused the team’s $800,000 salary offer.6 The market showed little interest in the recent hero and he ultimately signed for $600,000 with the Baltimore Orioles in February 1987. Although the contract was for two years, Knight’s lackluster 1987, in which he batted only .256, resulted in his being traded to the Detroit Tigers in February 1988. Now slowed by age (he was 35) and lingering injuries, Knight managed only a .217 average for the Tigers in ’88 and saw a brief power surge from the previous year dissipate. By the final months he was a part-time player, missing huge chunks of playing time throughout August and September. At season’s end, he was waived by the Tigers, and retired as a player.

Upon retirement, the energetic Knight briefly became the caddy for his still successful wife. It was an experiment that didn’t last long, as the two competitors would find themselves fighting on the golf course.7 Knight simultaneously shouldered the blame for the failed experiment, but also pointed the finger at Lopez. “I’m too intense. Nancy and I have always had this relationship where when we feel something, we express it. As a husband, I can do that. It doesn’t make any difference—I can tell her she looks heavy, or the clothes she wears are not good or her hair doesn’t look good, and she accepts it. But on the golf course, I could not say anything—right, wrong or indifferent.”8

Unable to leave the game that meant so much to him, Knight became an ESPN analyst until 1993, when he joined the Reds coaching staff, serving under his old Mets manager Davey Johnson. The Reds finished first in the strike-shortened seasons of 1994 and 1995. Because the postseason was canceled in ’94, Knight would have to wait until 1995 to once again participate in October baseball. The Reds swept the Dodgers in three games in the Division Series, but were then swept themselves by the Atlanta Braves in the Championship Series.

Despite Johnson’s success as the skipper of the Reds, his relationship with the team owner, the volatile Marge Schott, was precarious.9 After the 1995 season Johnson was fired and Knight was promoted to succeed him. Although he had been a coach for Johnson for three years, Knight had never managed before. His foray was less than successful. Leading a squad that included future Hall of Famer Barry Larkin, Hal Morris, and, ironically, Eric Davis, the team managed only a .500 record (81-81). The brawler side of Knight survived past his playing days, and made a memorable appearance in his short managing tenure. He was suspended for three games in May of 1997 for an altercation with umpire Jerry Layne. In the heat of the argument, he spit on Layne. After the infamous episode between Roberto Alomar and John Hirschbeck the previous September, the league was cracking down on spitting. In discussing the suspension, Knight’s made clear his passion for staying connected to the game: “I don’t mind paying a $10,000 fine, but let me stay with my ballclub. The worst thing in the world is to suspend me and get me away from my team. It hurts me; it crushes me.”10 He lasted only 99 games into the 1997 season before he suffered Johnson’s fate. Of the experience, and of working for Schott, Knight said, “That probably took years off my life. I was in the worst possible situation you could possibly be in.”11

Knight returned to ESPN and then, in 2002, again rejoined the Reds as bench coach after the team was purchased by Carl Lindner. Knight managed the squad for one final game, a victory, after manager Bob Boone was fired in the middle of the 2003 season. The next night he handed the reins over to Dave Miley. He left the Reds again after that season.

In 2007 Knight joined MASN, the television home of the Washington Nationals. He became the host of “NatsXtra,” the pregame and postgame show, and still filled that role as of 2016. In honor of his philanthropic work, Knight had a road named after him in 2013 on the campus of Phoebe Putney Memorial Hospital in his hometown of Albany. Ray Knight Way intersects with Nancy Lopez Lane, a poignant symbol considering that the couple divorced after 28 years of marriage. Despite the split, there was still an obvious affection between the two. According to Knight, Lopez’s contributions to the hospital far outweighed his own. “The only thing wrong (with the street sign at the intersection of Nancy Lopez Lane and Ray Knight Way) is that I am on the top. She should be on the top.”12

If there is someone who understands what it means to be on top, it’s Ray Knight. From a career that began at the completion of the dynastic Big Red Machine, saw the ultimate reward of World Series victory in the City That Never Sleeps, and continued as a part of the Washington Nationals, Knight was never been far from success. And for a brawler like Ray Knight, he wouldn’t have it any other way.

Notes

1 Richard Lemon, “On the Beach No More, Nancy Lopez and Ray Knight Score a Tie for Golf and Baseball,” People, April 25, 1983.

2 “Reds Trade Knight for Cedeno,” New York Times, December 19, 1981.

3 John Royal, “Cesar Cedeno and the Astros Career That Could Have Been,” Houston Press, July 9, 2012.

4 Lemon.

5 Joseph Durso and Thomas Rogers, “Scouting; More Speculation on Ray Knight,” New York Times, December 11, 1984.

6 “Orioles Sign Reluctant Knight,” Los Angeles Times, February 11, 1987.

7 Mal Florence, “Lopez Minus Part-Time Caddy Today: Husband Ray Knight Goes Home After Having Problems at Rancho Mirage,” Los Angeles Times, April 14, 1989.

8 Mike Penner, “Secret of Their Success Is Look but Don’t Help: Lopez and Knight Love Each Other, but He Couldn’t Cut It as Her Caddie,” Los Angeles Times, September 21, 1990.

9 Frank Ahrens, “The Johnsons: Not Your Traditional Couple,” Washington Post, November 17, 1997.

10 “Reds’ Knight Is Suspended,” New York Times, May 21, 1997.

11 Rick Maese, “Why’s Ray Knight So Excited?,” Washington Post, September 26, 2014.

12 Jennifer Maddox-Parks, “Meredyth Streets Dedicated to Nancy Lopez, Ray Knight,” Albany (Georgia) Herald. March 7, 2013.

Full Name

Charles Ray Knight

Born

December 28, 1952 at Albany, GA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.