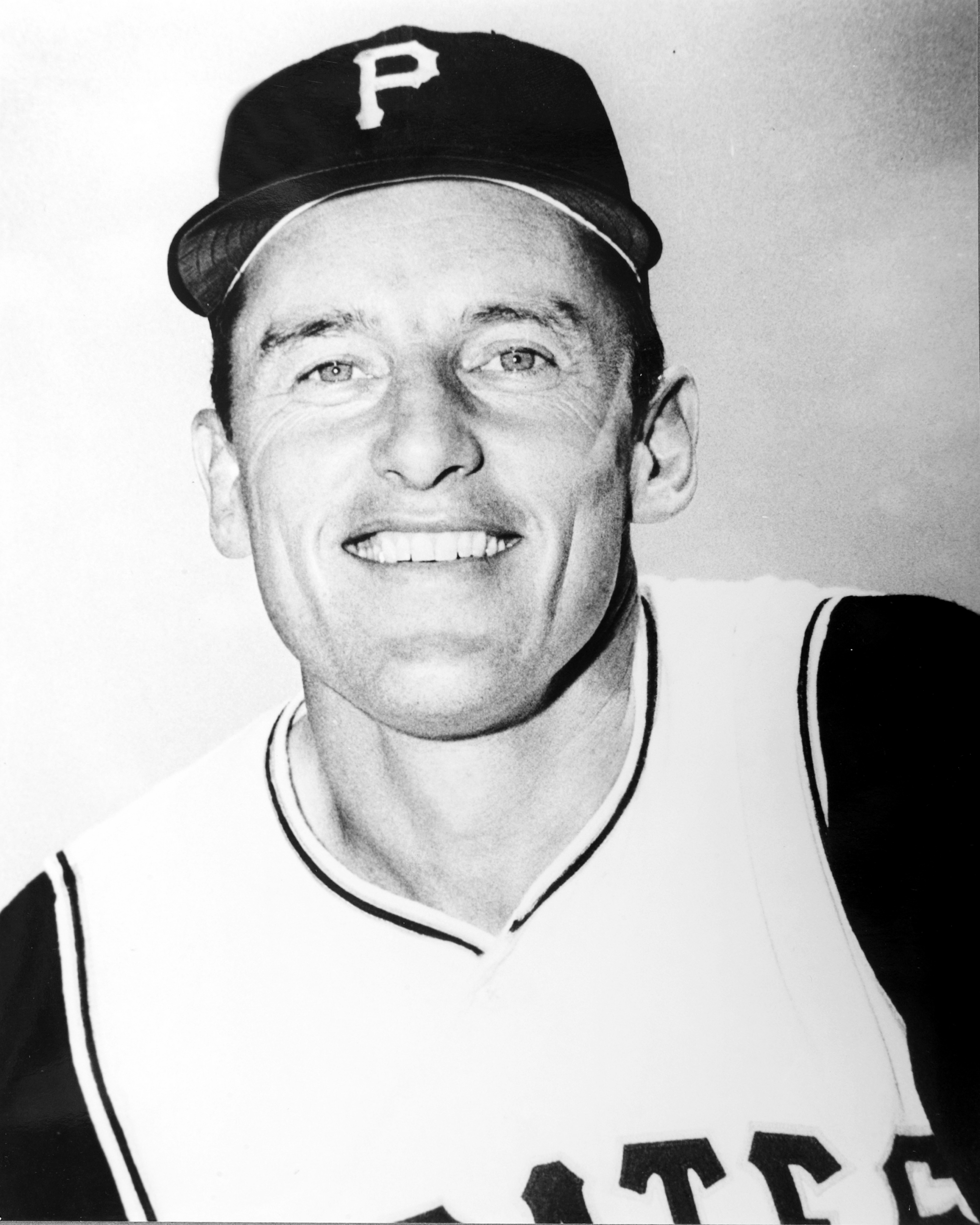

Vern Law

The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates had their fair share of heroes and players who had career years, but when all is said and done, without Vernon Law they might well have been just another team that came close to glory. Heading into 1960, Law had just turned 30 and was an eight-year veteran of the Pirates, having missed two years of baseball because of military service. His major-league won-lost record heading into the season was an unremarkable 82-86, tempered by pitching for mediocre or worse Pirate teams. Before 1959, his career record was 64-77, but he had shown promise in 1959 of what was to come when he won 18 games while losing only 9 for the fourth-place Bucs. His 20 complete games were tied for second best in the league and his 2.98 earned-run average was fifth best.

The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates had their fair share of heroes and players who had career years, but when all is said and done, without Vernon Law they might well have been just another team that came close to glory. Heading into 1960, Law had just turned 30 and was an eight-year veteran of the Pirates, having missed two years of baseball because of military service. His major-league won-lost record heading into the season was an unremarkable 82-86, tempered by pitching for mediocre or worse Pirate teams. Before 1959, his career record was 64-77, but he had shown promise in 1959 of what was to come when he won 18 games while losing only 9 for the fourth-place Bucs. His 20 complete games were tied for second best in the league and his 2.98 earned-run average was fifth best.

Thus, Law’s Cy Young year in 1960 did not exactly come out of nowhere. For the record, he won 20 games for the only time in his career, lost only 9, and with 18 complete games he tied Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette for the league lead. Although hampered by a sprained ankle, he won Games One and Four in the World Series and started the historic seventh game on three days’ rest. Although the Yankees batted .338 for the Series and the Pirates’ earned-run average was a collective 7.11, Law managed a credible 3.44 ERA against the Bronx Bombers in 18? innings of work. The Pirates certainly would not have won that crazy, lopsided Series without him.

Vernon Law’s path to World Series hero began in Meridian, Idaho, where he was born on March 12, 1930. His father, Jesse Law, was a mechanic who had seven children with his first wife, Audrey, who then died of consumption. Jesse then married Melva Christina Sanders and the two had three more children, of whom Vernon was the second.1 He was raised in a strict Mormon household on a farm outside Meridian. By the age of 12, Vernon was a deacon in the church and by 19 an elder. He attended a country school and, with his brother Evan, began playing hardball in the playground in the fifth grade.

During World War II Vernon’s father moved to Mare Island, California, near Santa Rosa, to work at a submarine base. When school was out for the year, the rest of the family followed and Vernon and his brothers were able to play more baseball in California.2 After the war the family returned to Meridian, where Law’s father worked as an auto and truck repair mechanic.3 By Vernon’s freshman year in high school, he had reached his full 6-foot-3 height and weighed 175 pounds, so he was recruited to the football team. He quickly became a star, in part because he could run the 100-yard dash in close to 10 seconds and could throw and kick a football long distances.

Law excelled at basketball and baseball in high school as well, despite having to get up at 5 a.m. for part-time jobs that provided the family with much-needed income. During his third year of high school, Meridian won the state championship in football, allowing opponents only six points all season, and in baseball. Vernon was the star pitcher and brother Evan his catcher and the cleanup hitter.4

After his junior year, Vernon spent the summer in Boise playing American Legion baseball because Meridian did not have enough players to field a team. Behind Law, the team won their district, state, and regional Legion championships, advancing to the sectional tournament in Billings, Montana, as one of the top 12 Legion teams in the nation. There he met and obtained an autographed ball from Babe Ruth, who was the banquet speaker.5 Meeting Ruth cemented Law’s desire to make a career for himself in baseball.6 He also began attracting professional scouts, spurred on by a 25-strikeout performance in a tournament game.

During his senior year, Law pitched a game against rival Payette that was 0-0 going into the ninth inning. Desperate to get someone on base, the Payette coach sent a 3½-foot-tall midget to bat as a pinch-hitter. With a number of scouts in the stands, Law struck him out on three pitches.7

One of the people in the stands that day was a Payette attorney named Herman Welker, who would later become a U.S. senator from Idaho. Welker had attended Gonzaga University with Bing Crosby, who had a minor ownership stake in the Pittsburgh Pirates, so Welker called Crosby to tell him about Law.8 The Pirates quickly dispatched scout Babe Herman to check on young Vernon but found they had stiff competition.9 Law had earned 12 letters in high school and had attracted scholarship offers from a number of colleges, as well as the attention of a number of major-league baseball teams.10

The Pirates offered a modest $2,000 bonus11 but the deciding factor may have come when, during a visit from Herman, the Laws’ phone rang. Vernon’s mother answered it and found herself talking to none other than Bing Crosby himself. He promised that Vernon would receive the best treatment with the Pirates12 and also promised an expense-paid trip to the World Series if Vernon and the Pirates ever made it that far. Thirteen years later, the Pirates made good on that promise.13 It probably did not hurt that the Pirates also signed Vernon’s brother Evan to a minor-league contract.

Three days after his high-school graduation in 1948, Vernon and Evan reported to the Santa Rosa Pirates in the Class D Far West League. The boys were back in the area where they had spent parts of two years growing up during World War II. Although Law was a work in progress, he showed promise, winning eight and losing five in 21 games. Although his earned-run average was 4.66, he struck out 126 batters in 110 innings, while walking 96. His club finished fourth in the eight-team league, but won the four-team playoffs, defeating the Klamath Falls Gems in seven games in the final.14

Law’s performance with Santa Rosa earned him a promotion to the Davenport Pirates of the Class B Three-I League for 1949. There he won only five games against 11 defeats but posted an impressive 2.94 earned-run average and allowed only 112 hits in 144 innings. His team again finished fourth in an eight-team league but won the league championship in the playoffs, sweeping the Evansville Braves in three games in the final round. Brother Evan played for the Greenville, Alabama, Pirates in the Class D Alabama State League, but was released after batting only .125.

Before leaving for spring training in 1950, Law married VaNita McGuire on March 3 in Logan, Utah.15 The couple had been dating since high school and would have five sons, Varlin, Vaughn, future major leaguer Vance Law, Veryl, and Veldon, and a daughter VaLynda.

Once the 1950 season began Law found himself promoted all the way to the New Orleans Pelicans of the Double-A Southern Association. He got off to a strong start, winning six of his first ten decisions with a stingy 2.67 earned-run average. On June 6 he was in Nashville preparing to start a game against the Nashville Vols when he learned of his call-up to the Pittsburgh Pirates.16 He was barely 20 years old.

Law’s big-league debut and first start came in Forbes Field on June 11 in the first game of a doubleheader against the Philadelphia Phillies and their young ace Robin Roberts. Those Phillies, better known as the Whiz Kids, would win their first National League pennant in 35 years that season, largely through winning an inordinate amount of one-run games.17 Law’s debut was no exception as he led 4-2 before the Phillies scored five runs in eighth and held on for a 7-6 win. A three-run double by Jimmy Bloodworth with the score tied 4-4 was the big blow. Still, Law pitched a complete game.

His second start was a no-decision five days later against the Boston Braves in Boston in a game the Pirates lost in the bottom of the ninth. Four days later Law again squared off against the Phillies, this time in Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium. He lost 7-3 to Russ Meyer as the Phillies, aided by misplays in the outfield, scored all their runs in the sixth and seventh innings.18 Law continued to pitch in bad luck for a woeful Pirates team that would finish in the cellar, 33½ games out of first place. He did win six of his last 11 decisions to finish with a 7-9 record in 27 games, 17 of which were starts. He completed five of those starts and ended his debut year with a 4.92 earned-run average.

Law’s 1951 season was very similar, as he won six and lost nine as the Bucs improved slightly to seventh place. He started 14 of the 28 games he appeared in as manager Billy Meyer continued to use him as a spot starter and in long relief, improving his ERA to 4.50. For both the 1950 and 1951 seasons Law’s earned-run average was above 5 as a starter and almost 1½ runs lower in games in which he relieved.

The Korean War was in full swing and Law knew that he would likely be drafted. Instead, after the season, he enlisted in the Army at Fort Eustis, Virginia, which had an active baseball program. He mostly played first base rather than pitch for the base team while missing the 1952 and 1953 major-league baseball seasons. While in the service, he played with or against Willie Mays, Johnny Antonelli, and Don Newcombe, as well as teammate Dick Groat.19 Law was mustered out of the service in December 1953, in plenty of time to get ready for the Pirates’ 1954 spring training.20

Branch Rickey had become the Pirates’ general manager in 1950 and his evaluation of Law suggested that he might be switched to an everyday player:

“Law…has a chance for the outfield. He is highly intelligent, a good athlete, a good runner, and very adventurous. Could easily be the best base runner in the Pittsburgh organization. He has never had an opportunity of hitting very much for he has always been a pitcher.”21

Law did, however, remain a pitcher. The Pirates team that he returned to had finished last in both 1952 and 1953 and was destined for the basement in 1954 and 1955 as well. Manager Fred Haney gave him plenty of work in 1954 both as a starter and reliever. He was only 5-13 as a starter but won four games in relief to finish 9-13 for the year. His earned-run average was an unsightly 5.51 and he gave up 201 hits in 161 innings. The two years of military service certainly had not advanced his baseball career but he did show promise. According to Wayne Terwilliger, Law threw a shutout against the New York Giants during a game in which the Giants were stealing signs and knew every pitch that was coming.22

Law improved to 10-10 in 1955 and, with 24 starts, he pitched 200 innings for the first time in his career. His earned-run average dropped to a respectable 3.81. On July 19 of that year, Mel Queen, who was slated to be the starting pitcher, came down with a stomach bug and Law was asked to pitch on three days’ rest and little notice against Lew Burdette of the Milwaukee Braves. Both teams scored early before both hurlers shut the door. The game went into extra innings tied at 2-2 and after nine more innings the score was still 2-2 and Law was still on the mound. After manager Haney finally pinch-hit for Law in the 18th, Bob Friend came in and gave up a run to put the Pirates behind heading into the bottom of the 19th inning. But the Pirates roared back to score two runs for a 4-3 win, with Friend the winning pitcher. In 18 innings of work, Law had thrown approximately 220 pitches, given up nine hits, struck out 12, and walked only two, all for a no-decision.23

Afterward Haney reported that in every inning from the 12th on he asked Law if he was getting tired. The answer was always the same, “No I’m fine.” When he finally pinch-hit for Law after 18 innings, he did so because he was afraid he would be run out of town if Law hurt his arm.24

Five days later Law took his regular turn and pitched a ten-inning, complete-game 3-2 victory over Chicago, giving up just four hits.25

The 1956 season was another long one for the Pirates and Law, even with the boundless energy and enthusiasm of new manager Bobby Bragan. The club did manage to climb out of the basement to seventh place, but Law struggled to an 8-16 won-lost record, going 7-13 as a starter. After five full seasons in the big leagues, his record stood at a cumulative 40 wins and 57 losses, with an earned-run average of 4.55.

The Bucs returned to the cellar in 1957 and in early August, GM Joe Brown replaced Bragan with Danny Murtaugh, who guided the team to a promising 26-25 finish. This was the year that Law finally started fulfilling his potential, putting together ten wins in 18 decisions with a sparkling 2.87 ERA, fifth best in the National League. However, Ruben Gomez of the New York Giants ended Law’s season prematurely by hitting him in the left ear with a pitch, rupturing his eardrum.26

During the 1957 season Law was thrown out of a game for the only time in his career and it was a game in which he was just sitting on the bench. The Pirates thought home-plate umpire Stan Landes was missing a lot of pitches and were complaining loudly and profanely. Finally Landes looked over to the dugout, pointed to Law, and to Law’s surprise, ejected him. Later in his report to the league, Landes said that he had thrown Law out because there was a lot of abusive language coming from the bench and he didn’t think Law, with his religious beliefs, should have to hear it.27

About the strongest language ever to come out of Law’s mouth was “Judas Priest,” when he was called out on a pitch he thought was not a strike.28 He did pitch on Sundays, generally only a day of worship for Mormons, believing that the church would want him to fulfill his contractual obligations.29

Law was generally reluctant to throw at hitters. In 1958, however, he precipitated a bench clearing brawl after throwing at San Francisco Giants pitcher Ruben Gomez. (That was the season the Giants had moved from New York.) Gomez was known as a head-hunter and had beaned Law the previous year. In this game, with the score 1-1 in the fourth inning, Gomez hit Bill Mazeroski after Maz had missed a home run on a long drive that was just foul.30 Manager Murtaugh instructed Law to knock down the first batter in the next inning. Law said, “Skip, it is against my religion. After all, the Bible says, ‘Turn the other cheek.’ ”

Murtaugh replied, “Well, it will cost you $100 if you don’t knock him down.”

Law paused for a second and said, “The Bible also says ‘those who live by the sword, die by the sword.’ ”31

Gomez happened to be the first batter and Law whizzed the first pitch right under his chin, sending him sprawling. Umpire Frank Dascoli started out to the mound to warn Law and Murtaugh raced out of the dugout to protect his pitcher. About that time Gomez made an obscene gesture at Murtaugh, who started for Gomez, precipitating an old-fashioned free-for-all.32

Teammate Roberto Clemente was the target of a lot of beanballs early in his career. On one occasion Clemente was laid flat in Philadelphia by a pitch right at his head. After grounding out weakly, he came back to the dugout just livid, cursing and yelling. Law told him, “Calm down. I’ll take care of this.” He proceeded to deck the first Phillies hitter, Richie Ashburn, prompting the umpire to warn both teams that the next pitch close to anyone’s head would cost $500 plus a five-day suspension.33

Law once hit Hank Aaron a glancing blow to the helmet after getting him out three times on balls away. After the game, however, Aaron said it was just as much his fault because he was leaning over the plate, looking for another pitch outside.34

Law’s teammates came to call him Deacon, since Law was an elder in the Mormon Church.35 Law did not proselytize his teammates, however, and he had their respect. They viewed him as a leader by example. Often his teammates would watch their language when around him, knowing that he did not swear. The opposition would sometimes try to rile Law by calling him names such as “dirty Deacon,” but he was unflappable and just went about his pitching business.36

In 1958 the Pirates shot up to second place, finishing eight games behind the Milwaukee Braves. Law struggled the first half of the season and at one juncture had a 9-11 record with an earned-run average of almost 5.00. But he won five of his last six decisions to finish with 14 wins against 12 losses, and in the process reduced his earned-run average to 3.96. He gave up 235 hits in 202 innings and some in the Pirates’ front office wanted to trade him. General manager Joe Brown refused but did want Law to stop relying on his curveball so much.37 It was a good decision because while the 1959 Pirates slipped to fourth place, Law at long last became the ace of the staff, winning 18 games and losing only 9. His earned-run average dipped to 2.98 and his 20 complete games were tied for second most in the league.

Thus, the stage was set for 1960 as Law and the Pirates would reach the pinnacle of success individually and collectively. Law trained hard in the offseason in Idaho, running as many as six miles a day and throwing to his brother Evan. It paid off as he won his first four starts before losing to the Giants on May 6.38 He was a clutch performer all season, for example ending an early-season four-game slide by beating the Dodgers 3-2 in LA and pitching the Pirates back into first place on May 29 with a win over the Phillies to bring his record to 7-1.39 In fact, the Pirates had only two four-game losing streaks in 1960 and each time Law ended the streak with a victory in Los Angeles.40

Thus, it was no surprise when Law, with an 11-4 record at the break, was named to his first National League All-Star team, joining seven other Pirate teammates.41 That was the second year of a four-year experiment of hosting two All-Star Games. The two 1960 games were played on July 11 in Kansas City and on July 13 in Yankee Stadium in New York. The National League won the first game, 5-3, in 100-degree heat as teammate Bob Friend got the win with three scoreless innings to start the game, while Law recorded a save by getting Brooks Robinson to fly out to Vada Pinson in center field and Harvey Kuenn to line out to Clemente in right for the last two outs of the game, both with two men on. Law then started and was the winning pitcher for the second game, pitching three scoreless innings to beat Whitey Ford as the National League blanked the American League, 6-0, on the day that John F. Kennedy won the Democratic nomination for president across the country in Los Angeles.42

Law continued to pitch well after the All-Star break as the Pirates finally broke away from the Braves and Cardinals. On August 29 he won his 19th game, but it would take him four attempts to get number 20. He finally secured his first and only 20-win season by defeating the Cincinnati Reds 5-3 in a complete-game performance at Crosley Field.43 For the regular season Law finished with 20 wins against 9 losses and a 3.08 earned-run average. He walked only 40 batters in 271 innings and pitched 18 complete games in 35 starts to tie Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette for the league lead. It was the only season in Law’s career in which he did not make a relief appearance.

The Pirates clinched the pennant on September 25 while losing to the Braves in Milwaukee. Afterward the Pirates celebrated with champagne in the clubhouse and on the team bus. In the midst of the hubbub aboard the bus, several of Law’s teammates restrained him while catcher Bob Oldis playfully yanked a shoe off his foot, spraining Law’s left ankle in the process.44 Although Law soldiered on in the World Series, starting Games One, Four, and Seven, he injured his arm while favoring his bad ankle and thereafter struggled for several years to regain his 1960 form.

In Game One, in Forbes Field, Law faced Art Ditmar, who had led the Yankees with 15 wins. In the first inning he got a slider too high to Roger Maris, who deposited it in the upper deck in right field. But the Bucs quickly got to Ditmar for three runs in the bottom of the inning and Casey Stengel pulled the Yankee ace in favor of Jim Coates. In the fourth, Bill Virdon in center field made a fine catch of a 407-foot drive by Yogi Berra with two on and no outs. Moose Skowron then singled to knock in a run before Law retired the last two hitters, stranding two runners. Pittsburgh had stretched the lead to 6-2 by the top of the eighth when Law gave up singles to Hector Lopez and Roger Maris to start the inning. Manager Murtaugh brought in ace reliever Roy Face, who promptly struck out Mickey Mantle, got Berra to fly out, and then struck out Moose Skowron to safeguard the four-run lead. A two-run pinch-hit home run by Elston Howard in the ninth made the final score 6-4.45

By the time Law’s start in Game Four, in Yankee Stadium, came around, the Pirates were down two games to one after losing two Yankees slugfests, 16-3 and 10-0. In the first inning, Law escaped a second-and-third jam with no one out by getting Maris to pop up and Berra, after an intentional walk to Mantle, to hit into a double play. Skowron hit a home run in the fourth to make it 1-0 but in the fifth inning Vernon helped his own cause by doubling in the tying run off Yankees starter Ralph Terry. Virdon’s Texas Leaguer drove in two more runs and gave the Pirates a 3-1 lead. In the seventh the Yankees scored their second run on a double and two singles before Face came in to shut the door. He retired all eight batters he faced to close out the 3-2 win.46

The teams split the next two games, the Bucs winning Game Five 5-2 behind Harvey Haddix and Face before the Yankee sluggers again broke loose for a 12-0 win behind Whitey Ford in Game Six. That set the stage for Game Seven.

Law was still nursing his injured ankle but started the deciding game, looking for his third win in the Series. Manager Murtaugh was hoping for five or six innings from his starter before turning the game over to Face. The game certainly started out as planned with Law holding the Yankees scoreless in the first two innings as the Pirates raced to a 4-0 lead off Bob Turley and Bill Stafford. In the top of the fifth Law got ahead of the first hitter, Moose Skowron, 0-2. He tried wasting a fastball outside, but left it over the corner of the plate and Skowron drove a line drive into the lower deck in right field for a home run. Law settled down to retire the next three batters, leaving the score 4-1.47

The Pirates failed to score in their half, so Law trudged out to start the sixth on his throbbing ankle. Bobby Richardson led off with a hard single to center, which got the bullpen going. Tony Kubek was next and drew a full-count walk, Law’s first of the game. Murtaugh bolted to the mound from the dugout and asked Law about his ankle. Law responded that his ankle was fine, admitting later that it was “a little white lie.” It didn’t convince Murtaugh, who told Law he didn’t want another Dizzy Dean on his hands, injuring his arm because of a bad ankle, and he called in Roy Face from the bullpen.48

Face promptly gave up a line single up the middle to Mickey Mantle and a three-run homer into the upper deck of the right-field bleachers to Yogi Berra. Berra’s drive was fair by inches; when the dust settled, the Yankees surged into the lead, 5-4, Law had a no-decision, and the stage was set for perhaps the most exciting World Series finish in history.49 The Yankees’ lead grew to 7-4 before the Pirates, aided immeasurably by Hal Smith’s three-run home run, scored five runs in the bottom of the eighth to regain the advantage, 9-7. The Yankees clawed back with two runs in the top of the ninth to tie and set the stage for Bill Mazeroski’s Series-winning home run off Ralph Terry to lead off the bottom of the last inning of the last game.

For the Series, Law finished with two wins and a 3.44 earned-run average in 18 innings of work. Only one other Pirates pitcher logged more than ten innings and that was the workhorse reliever, Face.50 Although the Cy Young Award is based on the regular season, Law certainly put an exclamation point on the award for his performance in the World Series, all on an injured ankle. Certainly the Pirates could not have come close to winning the Series without him. For the record, he tallied more than twice as many Cy Young Award votes as the runner-up, Warren Spahn.51 He also finished sixth in the Most Valuable Player voting, won by teammate Dick Groat.

As Law drove home to Utah after the Series, he felt weakness in his pitching arm, but was not overly concerned since he had the entire winter to rest. But it was still not right when he began his pre-spring-training workouts. It turned out that he had torn muscles in the back of his shoulder during the Series while favoring his bad ankle. It would take him three full years to recover.52

Law appeared in only 11 games in 1961, starting ten and struggling to a 3-4 record in late June before going on the disabled list in July for the remainder of the season as the world champion Pirates fell all the way to sixth place.53 The 1962 season saw some improvement as Law won 10 and lost 7 in 23 games and 20 starts. He pitched seven complete games and even threw two shutouts, but was still hampered by arm miseries as the Pirates improved to fourth, winning 93 games.

Although Law insisted in 1963 that he was throwing pain-free for the first time in three years, by August his record was only four wins and five losses while his earned-run average hovered just below 5.00. Manager Murtaugh suggested that Law voluntarily retire and Law reluctantly agreed, since it was clear that the Pirates had no plans to use him.54

In a 2006 interview, Law said that he didn’t have enough sense to quit. During the offseason, he said, he was given a blessing by a Mormon High Priest during a youth conference in Salt Lake City. According to Law, the Mormon Church believes in miracles and when he went from the conference and picked up a baseball, his arm was totally without pain.55 A couple of other teams showed interest that winter, but Law elected to attempt his comeback with the Pirates.56 He worked his way back into the rotation and finished 1964 with a 12-13 record, starting 29 games and completing seven, with five shutouts and a 3.61 era.

Law began 1965 with five straight losses, but the Pirates scored only five runs in those games, so manager Harry Walker never considered pulling him from the rotation. Law repaid the confidence by reeling off eight wins in a row as the Pirates surged into pennant contention.57 He finished the season for the third-place Pirates with 17 wins against 9 losses, and his 2.15 earned-run average trailed only those of Sandy Koufax and Juan Marichal. For his efforts, Law was named the National League’s Comeback Player of the Year, an award he was reluctant to receive “considering the implications.”58

Law went 12-8 in 1966, but he was losing his effectiveness. His earned-run average slipped to 4.08 and he gave up 203 hits in 177 innings. He struggled even more in 1967. He had won only two of eight decisions by August when he suffered a groin injury. On August 29 he retired again, this time for good. Law was 37 years old. He finished his career with 162 wins and 147 losses in a 16-year career, all with the Pirates. In 364 career starts, he recorded 119 complete games and 28 shutouts.

Although often overlooked, Law was a good hitting pitcher, batting .216 overall and smacking 11 career home runs. Three times he hit over .300 for the season, topped by a .344 average in 1951, and 12 times in his career he was used as a pinch-hitter. He even started one game in right field in 1954, and in August 1956 manager Bobby Bragan batted Law seventh in the lineup for four consecutive mound starts, ahead of future Hall of Famer Bill Mazeroski. Law was also considered an excellent baserunner and was used as a pinch-runner 23 times.

Law stayed close to the game after the end of his playing career, serving as the Pirates’ pitching coach in the late 1960s before becoming an assistant baseball coach at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah. He served in that capacity for 11 years, and tutored Jack Morris, among others,59 before accepting a position as pitching coach for the Seibu Lions in Japan’s Pacific League. After spending the 1979 and 1980 seasons in Japan,60 Law returned to professional baseball in the US as the pitching coach for the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League. In 1982-83 he was the pitching coach for the Denver Bears in the American Association for the White Sox organization61 before becoming the manager of the team in 1984. Although the Bears were in second place in early June, a midseason slump led to his dismissal in early July.62

Afterward Law scouted for the White Sox in the Utah area and spent a number of years in corporate sales. In 1987, when the Pirates celebrated their 100th anniversary, he was named the team’s all-time best right-handed pitcher.63 His son Vance, a 39th-round draft pick, was a major-league third baseman for 12 years for the Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago White Sox, Montreal Expos, Chicago Cubs, and Oakland Athletics. In 2000 Vance became the head baseball coach at Brigham Young University, with his father as a volunteer coach. Vernon regularly pitched batting practice for the Cougars well into his 70s.”64 He continued to live in retirement in Provo, Utah, with VaNita, his wife of more than 62 years, surrounded by his six children, 31 grandchildren, and 13 great-grandchildren.

Last revised: September 15, 2014

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Baseball – The Biographical Encyclopedia (Kingston, New York: Total/Sports Illustrated, 2000).

The Baseball Encyclopedia (New York: MacMillan Company, 1969).

Les Biederman, “A Long Road Back – But Law Made It,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1965.

John T. Bird, Twin Killing: The Bill Mazeroski Story (Birmingham: Esmerelda Press, 1995).

Jim Brosnan, The Long Season (New York: Harper & Row, 1960).

Dan Coughlin, “For Law, Order is a Way of Life,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 2, 1976.

Rick Cushing, 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates – Day by Day: A Special Season, An Extraordinary World Series (Pittsburgh: Dorrance Publishing Co., Inc., 2010).

Richard Deitsch, “Catching Up With … Vernon Law, Pirates Ace, October 10, 1960, Sports Ilustrated, May 28, 2000.

Lew Freedman, Hard Luck Harvey Haddix and the Greatest Game Ever Lost, (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2009).

Bill Furlong, “Law’s Spirit Matches Arm,” Baseball Digest, July 1960.

Dick Groat and Bill Surface, The World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates (New York: Coward-McCann, Inc., 1961).

Jack Heyde, Pop Flies and Line Drives – Visits With Players From Baseball’s Golden Era (Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford Publishing, 2004).

James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays – The Life, the Legend (New York: Scribner, 2010).

Colleen Hroncich, The Whistling Irishman – Danny Murtaugh Remembered (Philadelphia: Sports Challenge Network Publishing, 2010).

Lloyd Johnson and Miles Wolff, The Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, 2nd ed. (Durham, North Carolina: Baseball America, Inc., 1997).

Gene Karst and Martin L. Jones, Jr., Who’s Who in Professional Baseball (New Rochelle, NewYork: Arlington House, 1973).

Kerry Keene, 1960 – The Last Pure Season (Champaign, Illinois.: Sports Publishing Inc., 2000).

Nelson “Nellie” King, Happiness Is Like a Cur Dog – the Thirty-Year Journey of a Major League Player and Broadcaster (Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse, 2009).

Richard H. Letarte, That One Glorious Season – Baseball Players With One Spectacular Year (Portsmouth, New Hampshire: Peter E. Randall Publisher LLC, 2006).

Lee Lowenfish, Branch Rickey – Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2007).

Major League Baseball Productions, Baseball’s Greatest Games – 1960 World Series Game 7 (DVD 2010).

David Maraniss, Clemente – the Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2006).

Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2004).

Bruce Markusen, Roberto Clemente: The Great One (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 1998).

John McCollister, Tales from the Pirates Dugout (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2003).

John McCollister, The Bucs! The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates (Lenexa, Kansas: Addax Publishing Group, 1998).

Hub Miller, “The Law of the Pirates,” Baseball Magazine, June 1951.

Larry Moffi, This Side of Cooperstown – An Oral History of Major League Baseball in the 1950s (Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 1996).

John Moody, Kiss It Good-Bye – The Mystery, the Mormon, and the Moral of the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates (Shadow Mountain Press, 2010).

Bill Morales, Farewell to the Golden Era – The Yankees, the Pirates and the 1960 Baseball Season (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc. 2011).

Jim O’Brien, Maz and the ‘60 Bucs (Pittsburgh: James P. O’Brien, 1993).

Andrew O. O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., Inc., 2000).

Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game – 65 Players Remember Baseball’s Greatest Era – 1947-1964 (New York: Hyperion, 1994).

Richard Peterson, Growing Up With Clemente (Kent, Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2009).

Richard Peterson, ed., The Pirates Reader (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2003).

David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports: Baseball, Revised and Expanded Edition (Westport, Connecticut.: Greenwood Press, 2000).

Joseph Reichler, Baseball’s Great Moments (New York: Bonanza Books, 1983).

Jim Reisler, The Best Game Ever – Pirates vs. Yankees, October 13, 1960 (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2007).

Ed Richter, The Making of a Big-League Pitcher (Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1963).

Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996).

Michael Shapiro, Bottom of the Ninth – Branch Rickey, Casey Stengel, and the Daring Scheme to Save Baseball from Itself (New York: Times Books, 2009).

Wayne Terwilliger with Nancy Peterson and Peter Boehm, Terwilliger Bunts One (Guilford, Connecticut: Globe Pequot Press, 2006).

Frank Thomas with Ronnie Joyner and Bill Bozman, Kiss It Goodbye – the Frank Thomas Story (Dunkirk, Maryland.: Pepperpot Productions, Inc., 2005).

David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – The Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game (Lincoln, Nebraska.: University of Nebraska Press, 2001).

Chase Walker, “Inner Control Also Means Outer Control for Vernon Law, a … Shy Guy,” Guideposts, May 1956.

Warren N. Wilbert, The Greatest World Series Games (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2005).

www.byucougars.com/home/m-baseball.

Notes

1 John Moody, Kiss It Goodbye – the Mystery, the Mormon, and the Moral of the 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates, 19.

2 John T. Bird, Twin Killing: The Bill Mazeroski Story, 82.

3 Larry Moffi, This Side of Cooperstown – An Oral History of Major League Baseball in the 1950s, 187.

4 Moody, 45.

5 Bird, 82.

6 Jim O’Brien, Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 384.

7 Dick Groat and Bill Surface, The World Champion Pittsburgh Pirates, 133.

8 Moffi, 186.

9 Moody, 47-48, 65-66.

10 Welker and Herman apparently advised scouts from other teams to offer cigars to Law’s father as a way of currying favor. Of course, as practicing Mormons, Mr. and Mrs. Law abhorred tobacco. John McCollister, Tales from the Pirates Dugout, 88; Moody, 75-76; Moffi, 186. One source has Herman passing out stogies to competing scouts before they entered the Law’s house. See Richard Deitsch, “Catching Up With … Vernon Law, Pirates Ace, October 10, 1960,” Sports Illustrated, May 22, 2000.

11 Richard Peterson, ed., The Pirates Reader, 180.

12 Hub Miller, “The Law of the Pirates,” Baseball Magazine, June 1951, 228.

13 Moody, 76-77.

14 Miller, 228

15 Moody, 71-75; Chase Walker, “Inner Control Also Means Outer Control for Vernon Law, a … Shy Guy,” Guideposts, May 1956, 7-8.

16 Moody, 115-16.

17 Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III, The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant, 365-67.

18 Several sources have Law pitching his first two games against Robin Roberts and losing both because of fielder misplays. Bird, 83-84; Moffi, 192; Moody, 122.

19 James S. Hirsch, Willie Mays – The Life, the Legend, 154.

20 Moody, 124-27.

21 Andrew O’Toole, Branch Rickey in Pittsburgh, 47.

22 Wayne Terwilliger with Nancy Peterson and Peter Boehm, Terwilliger Bunts One, 117. It actually may have been a complete game 4-3 win over the Giants on May 31, 1954, since according to Retrosheet, Law did not have a shutout against the Giants in the applicable years, 1950, 1951, and 1952. Terwilliger was with the Giants in 1955 and so the game would have been before Terwilliger was a Giant, since he describes the game as one occurring before he joined the team.

23 Bird, 84-85; Moffi, 181; Moody, 141-44; O’Brien, 383.

24 Groat and Surface, 134; Moffi, 182.

25 Several sources incorrectly have Law pitching 13 innings with three days’ rest. Bird, 85; Moffi, 182; Moody, 145.

26 Hirsch, 287.

27 Jim Reisler, The Best Game Ever – Pirates vs. Yankees, October 13, 1960, 112; Groat and Surface, 134; Moody, 149-51.

28 Moody, 150-51.

29 Bill Furlong, “Law’s Spirit Matches Arm,” Baseball Digest, July 1960, 51; Moffi, 187.

30 Retrosheet. Moffi, 183, has a slightly different version.

31 Correspondence with Vernon Law on file with the author. See also John McCollister, The Bucs! The Story of the Pittsburgh Pirates, 160; David Maraniss, Clemente – The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, 111; Danny Peary, ed., We Played the Game, 471-72; Reisler, 111-12; McCollister, Tales from the Pirates Dugout, 90; Dan Coughlin, “For Law, Order Is a Way of Life,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 2, 1976 (clipping located in Law’s player file at the Baseball Hall of Fame Library).

32 Moffi, 184.

33 Moffi, 182-83; Moody, 152-53.

34 Lew Freedman, Hard-Luck Harvey Haddix and the Greatest Game Ever Lost, 24.

35 Moffi, 181.

36 Peavy, 294, 471.

37 Richard Peterson, ed., The Pirates Reader, 181.

38 Furlong, 51; Moody, 177-79.

39 Reisler, 118; Richard H. Letarte, That One Glorious Season – Baseball Players With One Spectacular Year, 289.

40 Kerry Keene, 1960 – The Last Pure Season, 105; Reisler, 117.

41 Letarte, 291; Bill Morales, Farewell to the Last Golden Era – The Yankees, the Pirates and the 1960 Baseball Season, 119-21.

42 David Vincent, Lyle Spatz, and David W. Smith, The Midsummer Classic – A Complete History of Baseball’s All-Star Game, 176-89; Morales, 121.

43 Groat and Surface, 99; Keene, 105; Reisler, 124; Letarte, 294.

44 Moody, 204-06; Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, 210. Another source has the culprit as Don Hoak. See Michael Shapiro, Bottom of the Ninth – Branch Rickey, Casey Stengel, and the Daring Scheme to Save Baseball From Itself, 223. Yet others list the “raucous” Gino Cimoli as the bad guy. Baseball – the Biographical Encyclopedia, 650; Law has always refused to identify the player involved except to say it was not a starting player, which would eliminate Hoak. Morales, 356.

45 Groat and Surface, 21-23.

46 Groat and Surface, 26-27.

47 Reisler, 125-26.

48 Reisler, 152-53. Of course, Dizzy Dean was injured coming back too soon from an injured toe, but the comparison was still apt.

49 Reisler, 159-61; Warren N. Wilbert, The Greatest World Series Games, 152-60; Richard Peterson, ed., The Pirates Reader, 187-198; Groat & Surface, 17-34; Joseph Reichler, Baseball’s Great Moments, 100-103.

50 The Baseball Encyclopedia, 2301.

51 Baseball – the Biographical Encyclopedia, 650.

52 Moody, 313.

53 Colleen Hroncich, The Whistling Irishman – Danny Murtaugh Remembered, 131.

54 Les Biederman, “A Long Road Back – But Law Made It,” The Sporting News, September 4, 1965, 3; Cushing, 356; Moody, 313-14.

55 Cushing, 356-57.

56 Biederman, 3.

57 Ibid.

58 Moody, 314-15.

59 Rich Marazzi and Len Fiorito, Baseball Players of the 1950s, 210.

60 Wayne Graczyk, ed., 1989 Japan Pro Baseball Handbook and Media Guide, 100.

61 David L. Porter, ed., Biographical Dictionary of American Sports – Baseball – Revised and Expanded Edition, 863.

62 “Law Fired – Denver Skipper Axed at Mid-Season, Baseball America, August 1, 1984, 11.

63 Cushing, 358.

64 Brigham Young University baseball website, www.byucougars.com/home/m-baseball.

Full Name

Vernon Sanders Law

Born

March 12, 1930 at Meridian, ID (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.