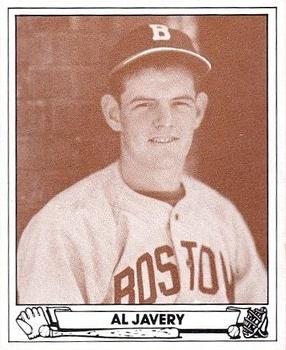

Al Javery

From 1942 to 1944, when World War II deprived major-league baseball of many of its top players, Al Javery was considered by some to be among the better pitchers left playing in the United States. At the very least he was one of the better players on the mediocre Boston Braves of the time. But it is difficult to say how the hard-throwing right-hander might have performed after the top players returned following the war; his shoulder gradually gave out and he was out of baseball by 1947. Though he made two All-Star teams and had double-digit wins four times, his baseball legacy is to be remembered more for having one of the more unusual nicknames in the game – “Bear Tracks” – and for being the target of one of Casey Stengel’s tales from his early days of managing. After his baseball career ended, Javery found success in an entirely different American pastime — bowling.

From 1942 to 1944, when World War II deprived major-league baseball of many of its top players, Al Javery was considered by some to be among the better pitchers left playing in the United States. At the very least he was one of the better players on the mediocre Boston Braves of the time. But it is difficult to say how the hard-throwing right-hander might have performed after the top players returned following the war; his shoulder gradually gave out and he was out of baseball by 1947. Though he made two All-Star teams and had double-digit wins four times, his baseball legacy is to be remembered more for having one of the more unusual nicknames in the game – “Bear Tracks” – and for being the target of one of Casey Stengel’s tales from his early days of managing. After his baseball career ended, Javery found success in an entirely different American pastime — bowling.

Alva William Javery was born June 5, 1918, in Worcester, Massachusetts, and grew up in the nearby town of Oxford. He and his older sister, Eldora, were the children of Armon and Flora (née Bartlett) Javery. Their first child, a son, died in infancy.

Armon was born in Connecticut and was of French-Canadian descent (the family name came to be pronounced JAY-very in the U.S., as opposed to the French way, ZHAH-very). In the 1910 U.S. Census, Armon was listed as a Navy sailor stationed in Japan. Following his marriage, Armon settled his family in Worcester County, Massachusetts, where he worked as a machinist. The Javery family was very active in the Oxford community and enjoyed partaking in athletics. Besides playing team sports like baseball and basketball, they were also fervent bowlers. Al’s parents often bowled in local tournaments. During his youth, if Al was not on a ballfield around Oxford, he could probably be found in a bowling alley.

By the time he was in junior high school, Al was receiving write-ups in the local paper for being “a constant nemesis to all opponents, tantalizing them with his slow ball and baffling them with his change of pace.”1 He starred as a pitcher all four years at Oxford High School and played on city-league teams as well. Tall and lean, Javery also excelled in basketball and ran cross-country in high school, but baseball was the sport that got him accepted into Worcester’s College of the Holy Cross, where former major leaguer Jack Barry coached. Javery was set to enroll in classes there in the fall of 1937, but first he attended a baseball school in nearby Gloucester, Massachusetts, run by the St. Louis Browns. Javery stood out among the nearly 300 young players at the school and caught the Browns’ attention. But Ray Werre, a former local minor-league player and a bird-dog scout in the area, was also familiar with Javery and recommended the young pitcher to Bob Quinn, president of the Boston Bees (as the club was then known).2 There was a report in January stating that Javery had signed to play with the Browns, but just before spring training began it was announced that Javery had officially signed a contract with Boston.

The first assignment in professional baseball for Javery was with Boston’s team in Lexington, Tennessee, in the Class D Kitty League in 1938. His 7-7 record and 4.70 ERA didn’t jump off the page, but he showed promise and was moved up to the Evansville Bees in the Class B Three-I league for 1939. Former major-league catcher Bob Coleman managed the Bees, and he saw something in Javery’s big overhand fastball and blossoming curveball. Javery usually pitched in relief for Coleman, but he finally received a starting assignment in the first game of a doubleheader on August 21 against Bloomington.3 He tossed a seven-inning shutout, allowing one infield hit, and convincing his skipper that he could contribute at the major-league level.4 If Javery were to get to the big leagues, it certainly wouldn’t have been with his bat; he finished last in batting in the entire league with one hit in 26 at-bats.

Javery had already signed a contract for 1940 to play for Boston’s Class A affiliate in Hartford, but on the recommendation of Coleman the Bees brought him to spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida. He held his own in exhibition games against the Yankees and Tigers and even struck out Jimmie Foxx when he faced the Red Sox. Bees’ manager Casey Stengel liked what he saw from the young pitcher, and Javery made the substantial leap from Class B straight to the majors. He made his debut on April 23, when he was brought in to pitch the last two innings of an 8-3 loss to Brooklyn. Javery was “cool as the proverbial cucumber under fire”5 and did not allow any runs in mop-up duty. He gave up two scratch singles and struck out three, including the first batter he faced in the majors, Dolph Camilli.

Javery lost his first four decisions before finally getting his first win on September 2. It was well-earned. The rookie entered the first game of that day’s doubleheader in the first inning with only one out after starter Dick Errickson had given up four earned runs. Javery gave up just two runs on three hits over 10 2/3 innings of relief that day, and Boston walked off with a victory in the 11th inning.6 Javery still holds the record for the longest relief outing for a first career win in the National League.7

Following his 1940 rookie season, Javery had an eventful offseason. He continued to refine his bowling game back home and participated in tournaments around New England. But the bigger event of that winter occurred in November when Javery wed his high school sweetheart, Martha Somers. Martha actually attended a rival school in the nearby town of Auburn, Massachusetts, where the couple would later reside.

Boston signed veteran hurler Wes Ferrell for 1941 to try and help shore up the pitching staff. Ferrell only won two games in a short stay with the Braves (they switched back from “Bees” in April), but he indirectly helped the staff by showing Javery his change of pace, giving the young pitcher a third offering to go with his fastball and curve. The tutoring paid off. Javery pitched his way into the starting rotation and won 10 games for the seventh-place Braves, finishing behind only Jim Tobin’s 12 victories. After making only four starts the previous year, Javery was now seen as a potential cornerstone for a rebuilding Braves team.

During spring training for the 1942 season, Javery “showed the most stuff” among Braves pitchers.8 Skipper Stengel selected him to be the Opening Day starter. At the end of July Javery’s record sat at 6-13, though his ERA was a fair 3.42. He heated up in August, winning his next six decisions and allowing only seven earned runs in the month to lower his ERA to 2.83. After completing a rain-shortened seven-inning one-hit game against the Dodgers on August 16, the Brooklyn Citizen said Javery “is pitching the best ball of any twirlers in the loop today.”9 He cooled off a bit in September and finished with an ERA of 3.03, but the Boston Globe still thought Javery “had developed into a front-ranking senior loop twirler.”10 Javery finished in the top 10 in the league in walks and hits allowed, but he was also second in the National League with a career-high five shutouts and led the majors with 37 games started. The Braves finished seventh in the NL for the fourth straight season, but Javery received three MVP votes and was considered one of the bright spots for the Braves to look forward to in 1943.

Standing 6-foot-3 and possessing both distinctive facial features and a lumbering walking style, Javery’s appearance made him ripe for a nickname. Early in his career there had been several attempts to outfit him with one. At various times he had been referred to as Boris or The Count, in view of how he evoked images of characters from Universal Pictures horror movies. He had been called L’il Abner, after the popular comic strip character (it was not an unfair comparison). But in 1942 teammate Tobin was credited with giving Javery the name that stuck throughout the rest of his career. He dubbed Javery “Bear Tracks” because of the heavy clomping steps he took around the mound.11 The name caught on in the newspapers, and it is still included on lists of some of the best baseball nicknames. (A contemporary pitcher, Johnny Schmitz, shared the monicker.)

After welcoming the birth of a son, Peter, in October 1942, and participating in more winter bowling tournaments, “Bear Tracks” Javery looked to continue his upward trajectory. Bob Coleman, Javery’s former boss in Evansville, had been promoted to the Braves coaching staff in 1943. Coleman would work with what was hopefully becoming a promising pitching staff, with Javery and Tobin expected to be leading contributors (youngsters Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain were both lost to the war effort).

Javery began wearing glasses in spring training, which he later said made a world of difference in his pitching. Looking back on his transition to wearing spectacles, he later joked, “I was always in a lot of trouble with the umpires, and I finally realized that I was the only one arguing.”12 The glasses indeed seemed to help, and 1943 was arguably Javery’s finest season. Some writers thought he was snubbed by not being selected for the All-Star game in 1942, but he wasn’t ignored for the 1943 edition at Shibe Park in Philadelphia. Javery hurled two shutout innings with three strikeouts in the midsummer classic, though the NL lost, 5-3. He continued where he left off after the All-Star break, winning nine games over the remainder of the season, including a complete game one-hit shutout against the Phillies in the second game of a doubleheader on September 16.

Javery finished the season with a career-high 17 victories, and he was third in the NL in strikeouts with 134. Although he led the senior circuit in hits and earned runs allowed (as well as errors by a pitcher), he finished 17th in league MVP voting. His performance helped the Braves climb to sixth place after being stuck in seventh place for four seasons.

Javery’s hurled 303 innings during the year, the highest count in the majors. He pitched nine innings or more 18 times, capped by a 14-inning effort on September 19 against Philadelphia. That wasn’t an unheard-of workload for a pitcher at the time, but the strain over the year may have been too much for Javery’s shoulder. As he prepared for the 1944 season (after another winter of constant bowling), he experienced arm soreness during spring training but was ready to go in time for his third straight season opener on April 18. A bigger concern that loomed for Javery was the U.S. military draft. He had an examination in the spring, but he was classified as 4-F because of varicose veins in his legs.13

Casey Stengel resigned as Braves manager in January 1944, and Coleman took over the helm. Like Stengel, Coleman counted on Javery to be a workhorse for the Braves staff. In the first of two games on June 22, Javery shut out the Phillies for 14 innings. But in typical Braves fashion, the offense could not muster even one run. Javery finally gave up a home run to Ron Northey in the 15th inning and took the tough-luck loss. He missed more than a week in mid-August with a pulled muscle near his right shoulder. Shortly after he returned, Javery pitched 11 1/3 innings over both games of a doubleheader with the Phils on August 27.

Although he wasn’t on pace to match his previous year, he again was selected to be a National League All-Star in 1944 (he did not play in the game). Javery finished third in the league in strikeouts, but he was also second in the league in walks. The Braves offense did little to help him either. The Braves finished sixth again, but were dead last in the NL in hits and batting average and topped only Cincinnati and Philadelphia in runs scored. Javery again finished with double-digit victories, but he cut it close; he finally secured win number 10 in the Braves’ final game of the season. His 19 losses tied for the second-highest total in the majors with teammate Tobin.

Before the 1945 season Javery was the subject of several winter trade rumors. But when the season kicked off on April 17, he was on the mound for Boston, even though there had been reports that he was again dealing with arm soreness. The idea of spending another season with a second-division club may not have provided encouragement, but his arm was mostly to blame when Javery got jolted in the opener, giving up five earned runs in two innings. The Braves kept him out of action for nearly two weeks to recharge his right arm. He appeared to recover over his next two starts, giving up only one earned run over 16 innings. Yet it was evident that his speed was down, and he was increasingly wild. He was roughed up for seven runs over five innings in two more appearances in the first half of May; his ERA stood at 4.30 as of May 15.

At that point the Braves thought they might have stumbled upon a solution to Javery’s arm problems. While tossing batting practice before a game, Javery was struck in the face by a comebacker off the bat of Mike Ulicny. The X-rays showed that his jaw had not been broken, but they did reveal that 10 of Javery’s teeth were infected and needed to be extracted. Doctors hoped that removing the teeth and clearing the infection would heal his arm and restore his lost velocity. Javery returned after a two-week layoff, but the dental work did not fix his fastball. In his first start back, on May 31 against St. Louis, Javery retired only one batter while allowing five runs before being taken out of the game.

Javery continued to perform poorly in workouts and did not appear in a game during the entire month of June. Following a series in Philadelphia, he was set to travel with the team back to Boston on June 7 so he could visit a physician there. When the train departed, however, Javery and teammate Tommy Nelson were nowhere to be found. No explicit reason was given for them being AWOL, but the Boston Globe noted that on a recent road trip there had been “some flouting of training rules by several Braves.”14 Both players were fined $300.

Javery finally returned to the mound on July 3 with an inning of relief against the Cubs. He was mauled again, allowing four earned runs in his one inning. The 27-year-old had always relied on a blazing fastball and seemed lost without it. After two more uneven outings in mid-August, Javery pitched in an exhibition contest against the Eastern League’s Hartford Senators on August 27. The weak-hitting Senators jumped on him for five runs, though they ultimately lost to the Braves, 10-7. Two days later, the Hartford Courant summed up the season for Javery. “He didn’t look fast enough to break a pane of glass … but the worst thing about him was his bedraggled appearance as he walked between the mound and the bench. He looked as if he didn’t care whether school kept or not.”15

Javery had another pitiful appearance against Chicago on September 9; he started the first game of that day’s twin bill but was again taken out before retiring two batters. Two days later, Javery failed to show up at the ballpark for the last game of the series. Following this second unexplained disappearance of the year, Javery was sent home for the rest of the season.

It was a disappointing end to a disappointing season. Javery mustered only two wins against seven losses and had an ERA of 6.28. Worse yet, he struck out only 18 batters over 77 1/3 innings. Outside of all the arm trouble, one could surmise that some of his problems in 1945 could also be attributed to spending one too many nights out on the town with his fellow Braves. Newspapers provided no explanation for why he twice went missing, but years later an article in Baseball Digest stated that Javery and teammate Nate Andrews, who battled alcoholism, dealt with the discouraging season by “seeking solace in bar rooms throughout the league.”16

Perhaps to clear his mind in preparation for the 1946 season, or maybe to give his arm a rest from bowling, Javery tried a new undertaking that winter. On the invitation of either a friend or family member, he packed up his wife and son and went out to Kokomo, Colorado, and spent the offseason working in a mine. The decision was reportedly almost fatal. One day in January, Javery was said to have walked away from a drilling site just moments before 15 tons of rock came crashing down where he had just been standing.17

New Braves manager Billy Southworth was optimistically hoping for Javery to make a comeback in 1946, but it was not to be. Javery was unimpressive in camp and was reassigned to work out with the minor-league Indianapolis Indians when Boston headed north to start the season. For the first time in five years, the Braves opened the season with a different pitcher on the mound, Johnny Sain.

Javery returned to the team in May, but he gave up five runs in his second game back and was optioned to the Toronto Maple Leafs in the Class AAA International League. The transaction finished Javery’s major-league career. He compiled a record of 53-74 and a 3.80 ERA in 205 games over his seven seasons.

Toronto soured on Javery after only two starts in which he failed to last more than three innings in either game. He was returned to Boston but was then sent to the Little Rock Travelers in the Class AA Southern Association.

Once the 1946 Southern Association season ended, Javery’s contract was sold to the Milwaukee Brewers in the American Association. He tried treatments to help his shoulder, but after failing to pitch at all for Milwaukee in 1947, Javery knew his pitching days were over. Rather than pursue surgery to help his shoulder, he instead went on the voluntary retired list. “I didn’t want them to operate if they didn’t know what they were going after,” he said.18 He attempted to resume his career in 1948 in smaller independent leagues. But after failed attempts with teams like South Grafton in the Blackstone Valley League and St. Hyacinth in Canada’s Provincial League, his baseball career was officially finished.

Javery refocused on bowling. He had had become quite proficient in the sport, picking up pointers over the years from pros who visited the area, such as future United States Bowling Congress Hall of Fame member Billy Golembiewski.19 He was accomplished in tenpin bowling but found the most success in candlepin bowling, a variation of the game that is popular in New England and Canada. He often faced off against Tracy Sanborn, a member of the International Candlepin Bowling Association Hall of Fame.20 In 1950 the two teamed up to take the Bay State doubles crown,21 and in 1951 they won a $5,000 national doubles championship prize. Javery also made occasional appearances in regionally televised bowling competitions.

Following his pitching days Javery managed a bowling alley near his home in Auburn, Massachusetts. He also worked as a patent clerk for a wire company and a maintenance man for a department store. In January 1974 Javery was remembered when he was among the guests at that year’s Boston Baseball Writers dinner. During the ceremony, where Hank Aaron was also honored, Javery was presented with the Ex-Brave award.22 In July 1977 Javery was interviewed for an article in the Boston Herald American newspaper. In the interview Javery reminisced about his baseball career, and he noted that he and his wife Martha enjoyed camping.23 He also stated that he had survived a few heart attacks in recent years (his father had died from a heart attack).

On August 16, less than a month after the article was published, the 59-year-old Javery collapsed from another heart attack while he was on a camping trip near Putnam, Connecticut. He died en route to the hospital. The news of Javery’s death unfortunately didn’t garner much attention; most of the national media focused on the death of Elvis Presley, which occurred on the same day. Martha Javery passed away in 2011, and both are buried at St. Roch’s Cemetery in Oxford.

In May 1947 a newspaper columnist related a tale from Sport magazine that involved Javery and Casey Stengel.24 The story recalled how Javery was removed from a game against Pittsburgh in the first inning after getting shelled for four runs and not retiring a single Pirate.25 After Javery was sent to the showers, Stengel asked catcher Phil Masi what kind of pitches Javery was throwing, to which Masi replied, “I don’t know, I haven’t caught one yet.” The story was told and retold several times over the next few years. The quote was a little different each time, and sometimes the location of the game or the name of the catcher changed, but the object of the story was always Al Javery. It wouldn’t be wrong to say that Javery had his share of bad outings over his seven seasons pitching for Boston. But it also wouldn’t be fair to leave him out when talking about memorable pitchers of the war years. If his arm had held out longer, maybe “Bear Tracks” would have still been an All-Star even after all the other players returned home.

Acknowledgments

The National Baseball Hall of Fame Library provided the player profile for Alva Javery.

Jacob Pomrenke assisted with compiling the Stathead data query on Javery’s first win.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and checked for accuracy by members of SABR’s fact-checking team.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted above and below, the author also referenced Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, SABR.org, and Ancestry.com.

Skelton, David E., “Nate Andrews,” SABR Baseball Biography.

Notes

1 “Woodward School Nine,” Evening Gazette (Worchester, Massachusetts), June 9, 1932: 26.

2 Jack McCarthy, “Al Javery – It Took Courage to Be a Brave,” Boston Herald American, July 24, 1977: 15.

3 Daniel W. Scism, “Double Win Trims Lead of Raiders,” Evansville Courier and Press, August 21, 1939: 6.

4 “Al Javery Twirls One-Hit Ball to Blank Bloomington, 2-0,” Evansville Courier and Press, August 22, 1939: 10.

5 “Javery Gets Stengel Nod and Does Nice Relief Job,” Boston Globe, April 24, 1940: 18.

6 Dodgers pitcher Hugh Casey matched Javery, pitching 10 innings after coming on in relief of starter Freddie Fitzsimmons with two outs in the first inning. Casey finally gave up the Braves’ winning run in the 11th inning.

7 Based on Stathead data query. The major league record belongs to Rube Vickers, who pitched 12 innings in relief for the Philadelphia Athletics in game one of a doubleheader on October 5, 1907, for his first career win. Vickers won his second game in game two of that doubleheader.

8 Harold Kaese, “Javery Lead-Off Pitcher for 1942 Model Braves.” Boston Globe, April 10, 1942: 20.

9 Lee Scott, “Dodgers Claim Javery Is One of The Best Right-Handers in League Today,” Brooklyn Citizen, August 17, 1942: 6.

10 Fred Barry, “Javery One Brave Who Won’t Quit,” Boston Globe, August 17, 1942: 10.

11 John Drohan, “Keep Pitching and Bums Cause No Trouble, Javery,” Boston Traveler, August 17, 1942: 24.

12 McCarthy, “Al Javery – It Took Courage to Be a Brave.”

13 “Javery of Braves Classified as 4-F,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, May 31, 1944: 6.

14 “Javery, Nelson Fined $300 for Missing Train,” Boston Globe, June 10, 1945: 18.

15 Bill Lee, “With Malice Towards None,” Hartford Courant, August 29, 1945: 11.

16 William G. Nicholson, “1945 – Baseball’s Most Chaotic Year,” Baseball Digest, Volume 30, No 8 (August 1971): 72.

17 “Al Javery Just Missed Being in Mine Cave-In,” Patriot Ledger (Quincy, MA), January 26, 1946: 6.

18 McCarthy, “Al Javery – It Took Courage to Be a Brave.”

19 Herb Ralby, “Fastball Pitcher Javery Slows to Garner Strikes in Bowling,” Boston Globe, January 29, 1961: 58.

20 Yes, there is such a thing. As of 2024, the Association is headquartered in Hampstead, New Hampshire.

21https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5b5742ec31d4dff47aa8dc09/t/5c59d393e79c701140163a6b/1549390739710/Tracy+Sanborn.jpg, (accessed February 2024).

22 George Bankert, “Writers to Honor Javery and Lepcio,” Patriot Ledger, December 26, 1973: 35.

23 McCarthy, “Al Javery – It Took Courage to Be a Brave.”

24 ‘Old Sarg,’ “In Sports Spotlight,” Pawhuska Journal-Capital (Pawhuska, Oklahoma), May 26, 1947: 4.

25 The game was likely July 3, 1943, when the Braves took on the Pirates at Braves Field. Javery allowed a single and three doubles before being pulled.

Full Name

Alva William Javery

Born

June 5, 1918 at Worcester, MA (USA)

Died

August 16, 1977 at Putnam, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.