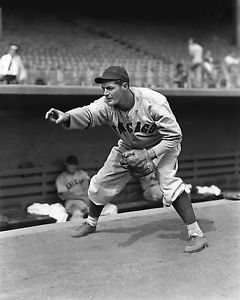

Bill Lee (“Big Bill”)

He wasn’t flamboyant like his contemporary Dizzy Dean and didn’t have a signature pitch like Carl Hubbell’s screwball, but stout right-hander Bill Lee of the Chicago Cubs had a five-year run in the 1930s when he could lay a legitimate claim to be the best pitcher, or at least one of them, in baseball. From 1935 to 1939, he won more games (93) than anyone except Red Ruffing and Paul Derringer and no one topped his 19 shutouts. Had there been a Cy Young Award, he would have won it in 1938, pacing the league wins (22) and ERA (2.66), and twice amassing streaks of at least 35 scoreless innings, while leading the North Siders to their second pennant in four years. But on the biggest stage in the sports, both Lee and his team faltered. History remembers the victors.

He wasn’t flamboyant like his contemporary Dizzy Dean and didn’t have a signature pitch like Carl Hubbell’s screwball, but stout right-hander Bill Lee of the Chicago Cubs had a five-year run in the 1930s when he could lay a legitimate claim to be the best pitcher, or at least one of them, in baseball. From 1935 to 1939, he won more games (93) than anyone except Red Ruffing and Paul Derringer and no one topped his 19 shutouts. Had there been a Cy Young Award, he would have won it in 1938, pacing the league wins (22) and ERA (2.66), and twice amassing streaks of at least 35 scoreless innings, while leading the North Siders to their second pennant in four years. But on the biggest stage in the sports, both Lee and his team faltered. History remembers the victors.

William Crutcher Lee Jr. was born on October 21, 1909, in Plaquemine, Louisiana, a town of about 5,000 residents situated on the western bank of the Mississippi River 17 miles south of Baton Rouge. His parents, William Lee Sr. and Annie (Garing) Lee, had relocated from Mississippi to the booming lumber town known for virgin cypress a few years earlier. The elder Lee became a successful timber buyer, providing the family, which grew to four with the birth of daughter Mary Louise, access to the most influential social circles in the picturesque antebellum town. By all accounts, Bill Jr. was a precocious youngster, who gravitated to sports at an early age. He attended Plaquemine elementary school and Plaquemine High School, where he played football, basketball, and baseball, and graduated in 1928.

Lee entered Louisiana State University in the fall of 1928, but his stint at the school on the bayou was short. An imposing figure, already 6-feet-3 and weighing almost 200 pounds, Big Bill played football and baseball his freshman year. The St. Louis Cardinals, in the beginning stage of developing the modern farm system, scooped up the 20-year-old hard-thrower and signed him to a professional contract.

A green, inexperienced hurler, Lee began his career in Organized Baseball in 1930 with the Greensboro (North Carolina) Patriots of the Class C Piedmont League where he struggled, walking almost as many batters (89) as innings pitched (94) with an ERA approaching 6.00. It was a completely different story the next season, when Lee overpowered opposition in the Middle Atlantic League, also Class C, as a member of the Scottsdale (Pennsylvania) Cardinals. Blazing a trail, Lee went 22-7 and set league records for most strikeouts in a game (18 against Hagerstown on June 10) and in a season (256). Promoted to the Columbus (Ohio) Red Birds, just one step below the majors in the Class AA American Association, Lee won his only two starts and cemented his reputation as “one of the most promising prospects” in the Cardinals farm system.1

Lee went 20-9 and 21-9 in his next two seasons with Columbus, emerging as one of the pre-eminent pitchers in the minors. The 1933 Red Birds rolled over competition, posting the league’s best record (101-51), led by their trio of league all-star hurlers: Lee, Clarence Heise (17-5), and Paul Dean (22-7). They eventually won the league playoff and the Junior World Series title, defeating the Buffalo Bisons of the International League in the best-of nine-series. Branch Rickey, the Cardinals GM and overlord of its chain gang, had a surfeit of young pitchers, giving him the luxury of selling players to infuse the team with much-needed revenue as the Great Depression squeezed finances. Chicago Cubs scout Pants Rowland, the former Chicago White Sox skipper who led the South Siders to the World Series title in 1917, tracked Lee and Dean for two seasons. Rickey refused to sell Dean, whose brother Dizzy was a star on the parent club, but in one his rare mistakes sold Lee for the then minor-league limit of $25,000 to his league rivals at the conclusion of the American Association’s regular season.2

Lee joined the Cubs at their spring facility on picturesque Catalina Island, located about 20 miles off the coast of Los Angeles. Coming off pennants in 1929 and 1932, the Cubs had slipped to third in 1933 (86-68), but were once against among the favorites to take the league crown. Lee’s success on the Cardinals farm did not guarantee him a spot on the North Siders’ staff, one of the club’s strong suits, led by a core of five right-handers, each of whom was coming off a season with at least 175 innings: Lon Warneke (18-13), Guy Bush (20-12), Charlie Root (15-10), Pat Malone (10-14), and Bud Tinning (13-6). The two biggest knocks against Lee had been his control (he walked 135, 115, and 114 batters in his last three minor-league seasons) and a reputation as a one-bad-inning hurler.

Sidelined by a severe case of the flu, Lee missed the first two weeks of the season and made his major-league debut on April 29 against the Cardinals at Wrigley Field, tossing three forgettable innings of relief, yielding two runs in mop up duty in a blowout loss. In his first start, on May 7, Lee mesmerized the Philadelphia Phillies with his curveball, tossing a four-hit shutout. In his encore five days later, also at the Windy City, he blanked the Brooklyn Dodgers on two hits. Sportswriter Tommy Holmes of the Brooklyn Eagle praised Lee’s “remarkable presence” and the “poise and deliberation of a veteran star,” and noted that Lee’s “easy three-quarters overhand delivery, a few fastballs and a real jug-handle curve” exasperated the Dodgers.3

Lee waited almost five weeks to pick up his next victory, a wild, 11-inning complete game against the Boston Braves on June 17. He surrendered the tying run in the bottom of the ninth, escaped a bases-loaded, one-out jam in the 10th, and them emerged as the winner, 3-2, when Chuck Klein blasted a walk-off home-run in the next frame.4 The Cubs engaged the New York Giants in a competitive pennant race through August, but slumped late in the season, going 13-16 down the stretch to finish in third place again (86-65). Lee (13-14, 3.40 ERA) proved to be durable, logging 214⅓ innings, the first of seven consecutive seasons and nine total times he exceeded the 200-inning barrier, completed 16 of 29 starts, occasionally relieved, and led the team with four shutouts.

Lee was a quiet, shy person, who never sought the spotlight. His good looks, dark hair and eyes, and square jaw earned him the sobriquet Handsome Bill from his teammates and sportswriters. By the time he joined the Cubs, he had already married his high-school sweetheart, Amanda Fallon. Together they had two children, Bill III and Mary Amanda.

The Cubs began the 1935 season with major question marks surrounding their overhauled pitching staff, which had lost four of its top six hurlers following the trades of longtime but disgruntled stalwarts Bush and Malone, and productive swingmen Jim Weaver and Tinning. Joining Lee and Warneke, coming off a league-best 22 victories, were workhorse southpaw Larry French from the Pirates and Tex Carleton, whose fighting with the Dean brothers (Dizzy and Daffy) in St. Louis forced his trade. Beat reporter Edward Burns of the Chicago Tribune summarily dismissed the remade corps, which also included 36-year-old graybeard Root and 23-year-old newbie Roy Henshaw, as “short of pennant class”; however, the staff had the last laugh in one of the most remarkable seasons in Cubs history.5

The Cubs started off slowly and trailed the front-running Giants by 10½ games on July 5. And then they got hot. One of the few consistent bright spots all season, Lee tossed what was probably the strangest game in his life on July 30 against the Pirates at Forbes Field. After French yielded four runs and failed to retire a batter in the first, Lee tossed nine innings of four-hit relief to win, 9-6. It was the Cubs’ 25th win in their last 28 games and pulled them to within one game of the Giants. The Cubs won the first contest of a twin bill the next day, then played .500 ball through September 2, at which time they were 2½ games off the streaking Cardinals’ lead.

With a favorable schedule keeping the Cubs in the Friendly Confines through September 22, the final month of the season proved to be one of the most exciting in Cubs history, fueled by pitching. General Lee, as sportswriters called him because of his Southern roots, was at the epicenter. On September 7, he blanked the Phillies on six hits for his fifth win in his last six starts, dating from August 17. He fired two more complete-game victories in eight days; the latter, against the Dodgers on September 15, was the Cubs’ 12th straight win and put them two games in front of the Redbirds. In his third straight start on three days’ rest, Lee outdueled Carl Hubbell, showing the “choicest bit of brilliance,” gushed sportswriter Irving Vaughan of the Tribune, tossing a six-hitter to beat the Giants, the Cubs’ 16th straight win.6

Facing the reigning World Series champion Cardinals in the first game of a doubleheader on September 28, Big Bill got the better of Dizzy Dean, in search of his 29th victory, tossing a six-hitter to win, 6-2 (both runs were unearned) to give the Cubs the pennant in dramatic fashion. It was Lee’s 20th victory of the season and also the Cubs’ 20th straight.

The Cubs eventually won 21 straight games to set a new major-league record. [The longest unbeaten streak is 26 games by the New York Giants in 1916; however, that included a tie between games 14 and 15; in 2017 the Cleveland Indians won 22 consecutive games to break the Cubs’ record.] During the streak, Cubs hurlers tossed 18 complete games and allowed three or fewer runs in 20 games; and 14 in the other. Lee (20-6, 2.96), Warneke (20-13, 3.06), French (17-10, 2.96), and Root (15-8, 3.08) helped the staff to the best team ERA (3.26) in the majors.

The 100-win Cubs were nominal favorites against the Detroit Tigers (93-58), but lacked the star power of the opponents, featuring future Hall of Famers Mickey Cochrane, Hank Greenberg, Charlie Gehringer, and Goose Goslin, as well as wildly popular Schoolboy Rowe. On October 4, Lee started Game Three in Chicago with the Series tied. He held the majors’ highest-scoring offense to one run through seven frames, but came unglued in the eighth, yielding three more runs, and was relieved by Warneke in a game the Tigers eventually won in the 11th. Lee’s only other appearance was in Game Five, when he tossed the final three innings in relief of Warneke, surrendering just a run in the Cubs’ 3-1 victory. The Tigers captured the title in the next game, 4-3, in the Motor City.

The Cubs were in a collective funk for most of 1936 save for a midseason stretch when they were well-nigh unbeatable. Widely predicted to capture the pennant again, the Cubs and Lee struggled early, but both heated up quickly in June. The Cubs reeled off 15 straight wins and Lee commenced a stretch of seven wins in nine decisions. Three days after blanking the Braves in Boston on June 25, Lee pitched on short rest to hold the Giants scoreless to complete a doubleheader shutout sweep at Coogan’s Bluff to push the Cubs into first place, a half-game in front of the Cardinals. It was the North Siders’ 21st win in their last 24 games.

With the Cubs kicking on all cylinders, Lee applied his “calcium brush,” noted New York sportswriter James P. Dawson, to record his third shutout in five starts, whitewashing the Giants again, this time in Wrigley Field, on July 13; it was Lee’s third 1-0 victory of the season.7 The stout Louisianan kept the Cubs (53-31) in first by a slim one-game margin by tossing a season-long 11-inning complete game to beat the Phillies in his next start, in the first game of a twin bill in Chicago; however, the Cubs played under .500 ball the rest of the season (34-36) to finish runner-up to the Giants, whose torrid .701 clip (47-20) led to the pennant. Lee (18-11) completed 20 of 33 starts, tied for the league lead with four shutouts, relieved 10 times, and posted a robust 3.31 ERA in 258⅓ innings.

Besides the trade of stalwart Warneke to the archenemy Cardinals in the offseason, the big news for the Cubs in 1937 took place at Wrigley Field, where the iconic ivy on the outfield wall was planted and the center-field scoreboard was installed as part of a two-year renovation plan that also included the construction of outfield bleachers. On the field, however, the North Siders produced almost a carbon copy of the previous year: early-season doldrums, a hot stretch, and a swoon; this year the Cubs added the wrinkle of a late-season surge, but still came up three games shy of the Giants, who won their third pennant in five years.

Lee’s shutout of the Giants on June 22 capped an 18-4 stretch for the North Siders, transforming a lackluster .500 record to a two-game lead in the standings. On August 3, Lee tossed a complete-game three-hitter, “compiled with neatness and dispatch,” opined Vaughn in the Tribune, needing just 87 minutes to beat the Phillies, 4-1, in the Windy City.8 A lifetime .168 batter, Lee went 2-for-3 at the plate and spanked one of his five career round-trippers in that contest, which gave the Cubs a commanding seven-game cushion. The Cubs appeared to be on their way to their fourth pennant since 1929; however, their lead dwindled throughout August, exacerbated by an injury (a “slipped muscle in his left side,” according to the Tribune)9 Lee suffered in his next start, on August 8. Sturdy before the muscle pull (12-9, 3.01), Less missed two weeks and struggled down the stretch (2-6, 4.96). For the first of three seasons, Lee led or co-led the NL in games started (34) and finished second in innings pitched (272⅓).

The Cubs’ weakness in 1937 was their pitching, and it looked no better in 1938 despite the offseason acquisition of the injured Dizzy Dean from the Cardinals. Lee was a question mark, too, as a sore neck and shoulder forced him to miss parts of spring training and required medical attention in San Antonio. After struggling the first month of the season, he made a remarkable turnaround, beginning on May 19 with a 10-inning five-hit shutout against the Giants and scoring the game’s only run, after reaching base on a walk, for just his second victory. That commenced a five-start stretch in which Lee tossed four shutouts, including three straight, yielding just one run and 26 hits in 46 innings.

He extended his streak of scoreless innings to 35⅓ in his next start, on June 7, another distance-going victory, to give the Cubs a 1½-game lead in the pennant race. Seemingly in the driver’s seat without a dominant team in the league, the Cubs unexpectedly collapsed, losing 19 of their next 28 games, leading to Grimm’s firing and his replacement by catcher Gabby Hartnett on July 21. During that free-for-all, Lee strutted his “stuff” on the national stage, tossing three scoreless innings and allowing just one hit in the NL’s 4-1 victory in the All-Star Game at Crosley Field.

The Cubs managerial change did not pay immediate dividends as the team fell as many as nine games off the Pirates’ lead and were in third place, seven games back on September 4. With their pennant hopes all but dashed, the Cubs kicked off another storied comeback, winning 20 of 23 games. History remembers Hartnett’s “Homer in the Gloamin’,” but without Lee, whom Vaughn described as the “hero of the team’s rise,” the Cubs would not have captured their fourth pennant in 10 seasons.10

With every game a must-win, Lee began the greatest month in his baseball life by shutting out the league leaders on 10 hits in Pittsburgh on September 5 to cut the lead to five games. Under extreme pressure, he hurled shutouts in his next three starts, becoming the first NL twirler since Philadelphia’s Pete Alexander to record four straight whitewashings, as part of 39 consecutive scoreless frames. Pitching on three days’ rest, Lee defeated the Cardinals in a route-going outing, 6-3, at Wrigley Field on September 26 to put the North Siders 1½ games behind the Pirates on the eve of a pennant-deciding three-game series between the two teams in Chicago. Lee pitched in each game. He recorded the final out to preserve Dean’s win and then an inning of scoreless relief in the next one, marked by Hartnett’s memorable walk-off home run to move the Cubs into first place by a half-game, though the pennant was far from secure with five games remaining.

Praised as the “iron man,” Lee took the mound for the fourth day in a row and went the distance to beat the Pirates, 10-1.11 The Cubs officially captured the flag two days later. Propelled by his remarkable performance in September (six complete-game victories in six starts, three high-leverage relief outings, and a 0.64 ERA in 56⅔ innings), Lee led the NL in wins (22), ERA (2.66), and shutouts (9), and also tossed a career-most 291 innings to finish second in the MVP vote behind the Reds’ Ernie Lombardi.

The Cubs were physically worn out, emotionally drained, and overmatched in the World Series against the New York Yankees, and were swept in four games. Lee started Games One and Four facing Red Ruffing, coming off his third of four straight seasons with 20 or more victories. Big Bill pitched well enough in the opener on October 5 in Chicago, yielding three runs in eight innings, but had just one run of support. The Yankees captured their third straight championship four days later, overpowering the Cubs in New York, 8-3. Lee lasted only three innings, charged with three unearned runs, all of which were scored after shortstop Billy Jurges’s poor throw on a routine inning-ending double play.

Lee and the Cubs came up short again on the biggest stage in baseball. Overachievers in 1938, the Cubs managed just 89 wins, the fewest for a pennant winner since the Cardinals in 1926. Career years by Lee and Clay Bryant (who notched 19 of his 32 lifetime wins) helped the staff to lead the majors in ERA (3.37), but they also covered up the underlying weakness of the club. Philip K. Wrigley, the aloof owner of the Cubs, who took over the team after the death of his father, William, in 1932, opened his bank account to sign players, but failed to grasp the importance of developing home-grown talent via the farm system, like the Cardinals or Yankees.

Mired in a post-World Series hangover, the Cubs never contended in 1939, playing sub-.500 ball as late as mid-June, and eventually finished in a distant fourth place, 13 games behind the Reds. Lee tossed a complete game on Opening Day to beat the Cardinals, 4-2, but he too seemed less sharp and struggled with his control for half the season. Named to his second and final All-Star team, he was pummeled for three hits and three runs, including a deep home run by Joe DiMaggio in his home park, Yankee Stadium, walked three, and was collared with the loss, 3-1. Lee turned it around in the season’s second half, winning seven straight decisions at one point. The durable workhorse of the staff (282⅓ innings), the 29-year-old Lee (19-15) tied his career high with 20 complete games and tied for the NL lead in starts (36) for the third straight year.

Lee never again reached the level of success he enjoyed in his first six seasons. In fact, his career is marked by two distinct phases: After compiling a 106-70 record and averaging annually 262 innings pitched with a 3.21 ERA, Lee followed with eight generally below-average seasons and a cumulative 63-87 slate. What happened? A confluence of factors precipitated Lee’s radical decline: Several years of overwork had taken their toll and his skills eroded rapidly even while he avoided major arm injuries; his eyesight deteriorated, leading him to wear glasses, still a novelty, especially for pitchers; his contract squabble with the increasingly notoriously cheap P.K. Wrigley took an emotional toll; and he played for bad teams.

After 14 consecutive winning seasons and first-division finishes, the Cubs entered a dark phase, finishing in fifth place (75-79) in 1940. For the next 22 seasons, the club managed only two winning seasons (1945-46), during a stretch of futility characterized by front-office ineptitude, a lack of vision for the team’s future, and the failure to adapt to a changing game. Lee was still considered the “premier member of the Cubs pitching staff” by beat reporter Irving Vaughan, but the burly hurler had a disastrous season, slipping to 9-17, and posted the league’s highest ERA (5.03 in 211⅓ innings, completing just nine of 30 starts.12 Opponents claimed his fastball had lost its zip, an ominous sign for an essentially two-pitch (curve/heater) hurler.13

In the offseason, Lee engaged with the Cubs’ new GM, James Gallagher, a former sportswriter, in a bitter contract dispute that played out publicly in the newspapers. According to the Tribune, Lee balked at the club’s lowball offer of $12,500, a slash of about 30 percent from his reported $18,000 salary the previous year.14 Gallagher, toeing Wrigley’s new austerity line in light of a dramatic 45 percent drop in attendance since 1938, threatened to reduce the contract to $10,000 if Lee refused to report to spring training. Lee called his bluff, but without leverage and no alternative to earn some 10 times the annual median income for an average US laborer, Lee had no choice but to grovel and capitulate.

On April 11 he arrived in Chicago and signed his contract — for $10,000 — three days before the season opened. Having already ceded the mantle of staff ace to Claude Passeau, who had been acquired early in the 1939 season and won 20 games the next year, Lee was in excellent condition despite not having participated in spring training. He tossed a five-hitter in his debut, on April 22, against the reigning World Series champion Reds, but lost, 1-0. He ended May by tossing his sixth consecutive complete game and boasted a 5-4 slate. And then the bottom fell out. He slumped and lost eight of nine decisions. In mid-August Lee was spiked by teammate Babe Dahlgren. The ankle wound became infected and he made only one start in the final seven weeks of the season.

Lee bounced back from an 8-14 season to split his 26 decisions, complete 18 games, and log 219⅔ innings in 1942. He also led the NL in fewest home runs permitted per nine innings for the second consecutive season, even though his 3.85 ERA was above the league average.

Relegated to a once-a-week starter in 1943, Lee saw his tenure with the North Siders come to an unceremonious end when he was traded on August 3 to the Philadelphia Phillies for journeyman catcher Mickey Livingston. Lee departed with the eighth most wins in team history (139), a total that has since been surpassed by only one Cubs pitcher, Fergie Jenkins (as of 2018); and fifth in innings pitched (2,271⅓), since surpassed by Jenkins and Rick Reuschel.

The Phillies were probably the only team in baseball that would have made the Cubs look like a well-run outfit. They were coming off five consecutive 100-loss seasons and had just one winning season since 1917. The club had been teetering on insolvency for the last few years and needed financial support from the NL to meet basic expenses in 1942, leading owner Gerald Nugent to sell the club to William D. Cox in February 1943. Cox informally changed the name of the club to the Blue Jays to polish its losing reputation. Not long before Lee’s arrival, rumors had circulated that Cox had placed wagers on his team. Lee won just once for the Phillies (4-12 cumulative record). In November Commissioner Kenesaw Landis forced Cox to sell the team.

Lee’s career was prolonged by World War II, which called hundreds of major leaguers to serve, diminishing the talent pool. Originally classified 4-F (physically unfit to serve) because of his eyesight, Lee was reclassified 1-A (fit to serve), raising doubts about his availability in 1944. Expected to be drafted any day, Lee chose not to report to the Phillies wartime spring-training camp in Wilmington, Delaware; instead, he prepared for season at home in Plaquemine.

Receiving notice that he probably wouldn’t be drafted given his age (34) and two dependents, Big Bill finally arrived in camp six days before the April 18 season opener. The club still finished in the cellar for the sixth time in seven years; however, skipper Fat Freddie Fitzsimmons, himself a 214-game winner who had retired the year before to become the Phillies manager, coaxed the most out of a staff of inexperienced and graybeard hurlers. Ken Raffensberger (13-20), Charley Schanz (13-16), Dick Barrett (12-18), and Lee (10-11) each logged in excess of 200 innings; combined with Al Gerheauser (8-16), the quintet started 146 of 154 games and logged a combined 1,112⅓ innings (79.7 percent of the team’s total). Lee caught lightning in a bottle on numerous occasions. He tossed two of his three lifetime two-hit shutouts, one of them against the Cardinals, whom he also blanked in a six-hit, 10-inning gem.

Lee stuck around for another three seasons, winning 19 games. He was sold to the Boston Braves in July 1945 and then came full circle by signing with the Cubs in the spring of 1947. After making 14 appearances, he was released on July 1 and accepted an assignment to Tulsa in the Double-A Texas League, hoping for a late season call-up. That never came, and the Cubs unconditionally released the 37-year-old hurler at season’s end, bringing his career to an end.

In parts of 14 big-league seasons, Big Bill compiled a 169-157 record, logged 2,864 innings with a 3.54 ERA, and tossed 29 shutouts. He posted a 76-33 slate in five minor-league seasons.

Lee was a lifelong resident of Plaquemine. Upon retiring from baseball, he became a successful businessman. After working as an insurance agent for Pan American Life, he went into banking and rose to the position of director of the Plaquemine Bank and Trust Company. On June 15, 1977, Bill Lee died at the age of 67. He was buried at the Protestant Cemetery in Plaquemine. He wife, Amanda, was buried next him upon her death in 1994.

Acknowledgments

This biography was edited by Len Levin and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Lee’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, the SABR Minor Leagues Database, accessed online at Baseball-Reference.com, The Sporting News archive via Paper of Record, SABR.org, the archives of the Chicago Tribune, Philadelphia Inquirer, and various other papers via Newspapers.com, and Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Notes from AA Training Camp,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1932: 5.

2 Associated Press, “Cubs Purchase Lee From Columbus,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 5, 1933: 11; Dan Daniel, “Sky’s the Limit: Rich Clubs Still Pay Highly for the Men They Want,” The Sporting News, February 15, 1934: 5.

3 Tommy Holmes, “Bill Lee Shows Worth Holding Stengel Clan to Only Two Singles,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 13, 1934: 39.

4 Irving Vaughan, “Cubs Split; Klein’s Homer Wins 2D Game, 3-2,” Chicago Tribune, June 18, 1934: 21.

5 Edward Burns, “Cubs Pitching Staf (sic) Short of Pennant Class,” Chicago Tribune, January 13, 1935: A3.

6 Irving Vaughan, “Cubs Win; Cards Keep Pace,” Chicago Tribune, September 20, 1937: 1.

7 James P. Dawson, “Lee Hurls Cubs Into First Place by Shutting Out Giants,” New York Times, July 14, 1936: 24.

8 Irving Vaughan, “Sox Lose 2; Cubs’ Homers Whip Phils, 4-1,” Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1937: 21.

9 Irving Vaughan, “Boston Defeats Sox, 5-4; Cubs Lose, 8-6,” Chicago Tribune, August 9, 1937: 22.

10 Irving Vaughan, “Bill Lee. Hero of Team’s Rise to League Lead,” Chicago Tribune, September 30, 1938: 25.

11 Ibid.

12 Irving Vaughan, “Lee Hammered For Nine Hits in Seven Innings,” Chicago Tribune, April 3, 1940: 23.

13 John Whittaker, “Specialty Sports,” The Times (Hammond, Indiana), September 5, 1940: 15.

14 Irving Vaughan, “Dykes Irked as Rain Delays Sox; Passeau Drops in on Cubs by Air,” Chicago Tribune, March 2, 1921: 29.

Full Name

William Crutcher Lee

Born

October 21, 1909 at Plaquemine, LA (USA)

Died

June 15, 1977 at Plaquemine, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.