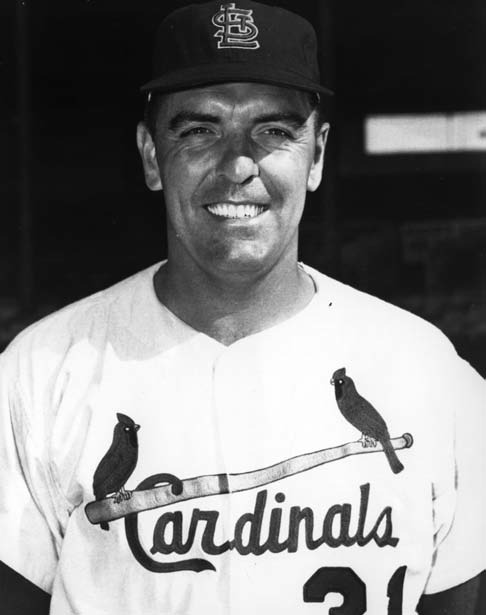

Curt Simmons

Curt Simmons left the visiting dugout and was moving through the bowels of Yankee Stadium toward the visitors’ locker room when a roar erupted from the Yankee Stadium crowd. Simmons knew the third game of the 1964 World Series was over, but he had given the St. Louis Cardinals eight solid innings, allowing only four hits. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane had pinch-hit for Simmons in the top of the ninth inning. With the score tied 1-1 in bottom of the ninth, reliever Barney Schultz was now on the mound. Mickey Mantle remarked to an exhausted Jim Bouton, the Yankees’ starter, “I’m gonna hit one outta here.” Mantle hit Schulz’s first pitch, a knuckleball, into the third tier of the right-field stands. Simmons nonetheless could take some pride in his outing; at the age of 35, he had finally pitched in the World Series. He’d missed out on one when he was 21, the youngest of the Philadelphia Phillies’ 1950 Whiz Kids.

Curt Simmons left the visiting dugout and was moving through the bowels of Yankee Stadium toward the visitors’ locker room when a roar erupted from the Yankee Stadium crowd. Simmons knew the third game of the 1964 World Series was over, but he had given the St. Louis Cardinals eight solid innings, allowing only four hits. Cardinals manager Johnny Keane had pinch-hit for Simmons in the top of the ninth inning. With the score tied 1-1 in bottom of the ninth, reliever Barney Schultz was now on the mound. Mickey Mantle remarked to an exhausted Jim Bouton, the Yankees’ starter, “I’m gonna hit one outta here.” Mantle hit Schulz’s first pitch, a knuckleball, into the third tier of the right-field stands. Simmons nonetheless could take some pride in his outing; at the age of 35, he had finally pitched in the World Series. He’d missed out on one when he was 21, the youngest of the Philadelphia Phillies’ 1950 Whiz Kids.

In 1946 and 1947, nearly every major-league club was interested in signing Curtis Thomas Simmons, a schoolboy phenom born in Egypt, Pennsylvania, on May 19, 1929. Looking at what he did during his high-school years, it was easy to see why. He had led his Whitehall High School team to three straight Lehigh Valley championships, and the Coplay American Legion team to two state championships.

During his senior year in high school, in 1947, Simmons batted .465 with two home runs, three triples, and six doubles. On the mound he struck out 102 batters and gave up only 12 hits in 43 innings. He threw two no-hitters, three one-hitters, and two four-hitters. In one game he struck out 20 of the 21 batters he retired.1

Simmons also played high-school basketball and football, but his father wouldn’t let him play football in his senior year. Curt was disappointed, but his father, Larry Simmons, didn’t want him to jeopardize his baseball promise by getting injured.

Simmons played in the Pennsylvania American Legion All-Star Game at Shibe Park (later Connie Mack Stadium), striking out seven of the nine batters he faced, and was the MVP of the East-West All-Star game, played at the old Polo Grounds in New York. (Simmons showed the author a photo of him flanked by managers Ty Cobb and Babe Ruth.) Simmons pitched the first four innings before Ruth moved him to the outfield. He singled and tripled for the victorious East team. Having made a similar move in his own career, Ruth advised Simmons afterward to give up pitching and stay in the outfield.

By the spring of 1947 three teams, the Phillies, Detroit Tigers, and Boston Red Sox, were still in the running for the left-handed schoolboy. About a week before his high-school graduation, his father and Phillies scout Cy Morgan organized an exhibition game that pitted Simmons and the Egypt town team against the Phillies. The Phillies players were not happy playing on an offday, but their lineup featured Jim Tabor, Emil Verban, Johnny Wyrostek, Howie Schultz, Lee Handley, and Del Ennis. Unknown at the time, the 21-year-old Ennis was the first of the Whiz Kids. Simmons would soon be the second. In the exhibition game he struck out the first two batters, Jack Albright and Johnny Wyrostek. The game was tied, 4-4, when it was called because of darkness. Simmons struck out 11, walked three, and gave up seven hits. His team committed five errors and allowed two unearned runs.

After graduation Simmons signed with the Phillies for $65,000, becoming one of the first of the postwar bonus babies. The Red Sox had offered $60,000 but Larry Simmons had offered to let the Phillies match the offer. (Before Simmons signed, the New York Giants offered him $125,000, but the Simmons family kept to its promise.)

Curt Simmons grew up during World War II and before Little League. “We would play pickup games on open fields and behind the schools until we were old enough for American Legion ball,” he recalled. “Some kids had bats, we used tire-tap balls or some kid had a real ball. I remember us walking four miles to play another town. We didn’t have coaching then – my father was working in a cement mill and didn’t have time for baseball. Times were different. A lot of my stuff comes natural to me.” He credited much of his success to his high-school coach, Bud Nevins, who had been a catcher in the Cardinals chain. Simmons’s American Legion coach, Sam Balliet, had advised him against signing a $150 contract with the Allentown Red Birds while he was a high-school sophomore.

Simmons signed his contract with the Phillies on June 16, 1947, and was assigned to the Wilmington Blue Rocks of the Class B Interstate League, where he posted a 13-5 record. The Phillies called him up after the Interstate League season ended. The 18-year-old Simmons’ first major-league start was the last game of the 1947 season, against the home-run-hitting New York Giants in Shibe Park. Giants slugger Johnny Mize, who was tied with Pittsburgh’s Ralph Kiner for the league home-run lead, was batting leadoff to perhaps get more at-bats. Simmons walked six but kept the Giants from scoring for eight innings, gave up a scratch run in the ninth, and won a five-hitter, 3-1, with nine strikeouts. Mize got a broken-bat single in five attempts.

Because Simmons was a bonus baby, he was allowed only one year in the minor leagues before being placed on the major-league roster. Shortstop Eddie Miller was picked up in a trade and when he saw Simmons he commented, “Kid, you signed for more than I made during my whole career.” Simmons stuck with the Phillies through the next two seasons; they could be best described as learning years: Pitching coach George Earnshaw tried to change his delivery. Simmons stepped toward first base and threw across his body, and the coaches thought he would hurt his shoulder. After going 7-12 in 1948, then 4-10 in 1949, he was told to return to his old delivery.

For the Phillies 1950 was magic; all the pieces were in place. Del Ennis and Jim Konstanty, Granny Hamner and Willie Jones, Dick Sisler and Curt Simmons had career years. By the end of August Simmons and Robin Roberts had both won 17 games, and the Phillies held a seven-game lead over second-place Brooklyn. But the pitching faltered, and in early September the Phillies were on the verge of collapse. Then, because the US was fighting a war in Korea, Simmons’s National Guard unit was activated. Bubba Church, who had eight wins, was slammed in the face with a ball off the bat of Cincinnati’s Ted Kluszewski, and Bob Miller (11 wins) developed back problems and was never again effective. Russ Meyer and Ken Heintzelman were not the same pitchers they had been in ’49, Meyer winning nine and Heintzelman only three. Nonetheless, the Phillies won the pennant with last-day heroics from Richie Ashburn, Roberts, and Sisler. Simmons finished the season 17-8 with a 3.40 ERA.

For the Phillies 1950 was magic; all the pieces were in place. Del Ennis and Jim Konstanty, Granny Hamner and Willie Jones, Dick Sisler and Curt Simmons had career years. By the end of August Simmons and Robin Roberts had both won 17 games, and the Phillies held a seven-game lead over second-place Brooklyn. But the pitching faltered, and in early September the Phillies were on the verge of collapse. Then, because the US was fighting a war in Korea, Simmons’s National Guard unit was activated. Bubba Church, who had eight wins, was slammed in the face with a ball off the bat of Cincinnati’s Ted Kluszewski, and Bob Miller (11 wins) developed back problems and was never again effective. Russ Meyer and Ken Heintzelman were not the same pitchers they had been in ’49, Meyer winning nine and Heintzelman only three. Nonetheless, the Phillies won the pennant with last-day heroics from Richie Ashburn, Roberts, and Sisler. Simmons finished the season 17-8 with a 3.40 ERA.

In the World Series, the Yankees swept the Phillies. Simmons was on a ten-day pass from the service, but was reduced to the role of spectator after Baseball Commissioner Happy Chandler ruled him ineligible for the Series.

What would have happened if Simmons had not been called into military service? How would that have affected the team? Maybe the September swoon would not have happened. Maybe the Yankees’ sweep would have never happened. Simmons said in March 2009, “Right after I had been activated (in 1950) Phillies owner and club president Bob Carpenter said don’t worry, he was going to get me out of it – it never happened. …”

The Phillies expected to win several more pennants during the 1950s, but Simmons spent all of 1951 on military duty, and the Phillies slid to fifth place with a 73-81 record. “Not having Curt Simmons all year in really hurt us in 1951,” manager Eddie Sawyer said. But Simmons returned from the service in 1952 and, without the benefit of spring training, went 14-8. He was the starting pitcher for the National League in the All-Star Game, giving up one hit in three innings as his team got a 3-2 victory in the rain-shortened game. (Bob Rush was the winning pitcher.) Simmons posted a 2.82 ERA and led the league with six shutouts. The Phillies won no more pennants in the ’50s, but with Roberts a habitual 20-game winner and Simmons winning 14 to 16 a season, they stayed in the first division from 1952 through 1955.

In June 1953 Simmons cut off part of his left big toe while mowing his lawn and was out for a month. Three weeks before the accident he had pitched perhaps the best game of his major-league career, a one-hit shutout of the Milwaukee Braves. Bill Bruton led off the Milwaukee’s first with a single, then Simmons retired 27 straight batters, striking out ten. Simmons returned to the Phillies’ rotation in time to pitch one inning in the All-Star Game, and he finished the season with 16 wins and 13 losses (3.21 ERA). Simmons said of his injury, “I always felt the effect of that accident was exaggerated.” The Phillies finished tied for third with St. Louis behind the Dodgers and Braves.

In 1954 Simmons posted the best earned-run average of his career (2.81), ranking third in the National League – though his won/loss record was 14-15, reflecting the team’s 75-79 fourth-place finish. Roberts was 23-14. The Whiz Kids began to fade away; Dick Sisler, the hero of the pennant-winning game in 1950, had left after 1952.

Simmons slipped to 8-8 in 1955, with an elevated 4.92 ERA. He rebounded to 15-10 in 1956 and cut more than a run and a half off his earned-run average (3.36). Simmons more or less replicated his 1956 performance the next year (12-11). He started the 1957 All-Star Game, and had back-to-back starts (May 30 and June 5) in which he pitched ten innings. By 1958 the Phillies were back in the cellar and arm woes had finally come to a climax for Simmons. He won only seven games and lost 14. Richie Ashburn was sent to the Chicago Cubs. Roberts and Simmons were the last of the Whiz Kids still with the Phillies in the beginning of 1960.

Much of the Phillies’ downward spiral was blamed on several factors: Simmons’ inability to become a 20-game winner; owner Bob Carpenter’s refusal to sign African-American ballplayers (Roy Campanella, Junior Gilliam, and Hank Aaron were available for the asking in 1947 and 1948), and the drying up of the farm system once the Whiz Kids were promoted to the big leagues.

Simmons missed most of the 1959 season, healing from a sore shoulder and elbow surgery. Throwing across the body had caught up to him. Even in his good years, his arm was sore after every outing. But he went to spring training with the Phillies in 1960 with his arm feeling good. “After a year away, I was pressing like a kid,” he said. He started the 1960 home opener, but gave up two home runs in the first inning and was lifted in the second inning. He had three more rocky no-decision outings, then, after 13 years with his hometown team, was unceremoniously released while the Phillies were in San Francisco. He got the news from Robin Roberts, his roommate. He got coach fare back to Philadelphia and was soon on the telephone looking for a job. The Orioles wanted Simmons to come to Baltimore for a workout, and the Pirates offered him a job in Triple-A Salt Lake City. Cardinals manager Solly Hemus, a former Phillies teammate, asked about his arm and Simmons said it was fine. Hemus urged Cardinals general manager Bing Devine to sign Simmons. Devine agreed, signing Simmons for $25,000 – $5,000 more than the Phillies were paying him.

At 31, Simmons said, “I’m a pitcher now, no longer a thrower. I can pitch to spots and I don’t give in to hitters.” Hemus placed him in the starting rotation on June 19. Simmons won seven games and lost four for the Cardinals with a 2.66 ERA and after the season was voted the Comeback Player of the Year by the St. Louis baseball writers. In 1961 he finished third in the league with a 3.13 ERA. In 1962 he defeated the Los Angeles Dodgers twice in the last ten days of the season to help force the Dodgers into a pennant playoff with the Giants. In the first of those two games, he was making an emergency start against the Dodgers’ Sandy Koufax after Bob Gibson fractured his ankle during batting practice.

In late 1963, during a 19-of-20 Cardinals win streak, Simmons was 4-0 with three shutouts. He finished 15-9. Then he became a big winner in 1964, the year of the Cardinals’ surge and the Phillies’ great collapse. He was 11-8 at the end of July, then finished with an 18-9 record. His final 1964 win was the last game of the Phillies’ ten-game losing streak. He no-hit the Phils into the seventh inning while the Cards gave him an 8-0 lead; he won, 8-5. This win, coupled with the Reds’ extra-inning loss to Pittsburgh, propelled the Cardinals into sole possession of first place. Against the Phillies Simmons was 19-6 since his release in 1960, and in 1964 he went 4-0 with one no-decision in a game the Cardinals won. Besides Game Three of the World Series, Simmons also started the sixth game. After getting a no-decision in Game Three, he was the losing pitcher in Game Six, giving up three runs in 6? innings before the Yankees plated five runs against two of the four St. Louis relievers, to win 8-3. The Cardinals bounced back the next day to win Game Seven.

Hank Aaron, a right-handed batter, hit six of his 755 home runs off left-hander Simmons, but told a sportswriter that Curt was the hardest on him. “Speed had nothing to do with it,” Aaron said. “It was that motion of his. He would turn his body, give me a view of his backside, then he would throw and I wouldn’t see the ball until a split second before he would let it go … then it come floating in like plastic.”

Simmons slumped to 9-15 (4.08 ERA) in 1965 and was 1-1 in 1966 when he was sold to the Cubs on June 22 (joining old teammate Robin Roberts). Simmons won seven games and list 14 for the Cubs during the rest of 1966 and the first four months of 1967 before Chicago sold him on August 7 to the California Angels. He was 2-1 with the Angels with a 2.60 ERA, but wanted to retire, be with his family, and help restore a golf course in Pennsylvania that he and Roberts had purchased, and the Angels gave him his release after the season. During a 20-year career, he won 193 games and lost 183 with an ERA of 3.54.

Simmons made one brief return to baseball, as part of the Phillies’ minor-league instructional staff in March 1970. He spent most of his post-retirement career managing his and Roberts’ golf course, the Limekiln Golf Club near Ambler, Pennsylvania (Robin Roberts, Jr. later took over the reins of the club.) In 2011 Simmons and his wife, Dorothy (Ludwig) Simmons, lived next to a fairway of the golf course. When they were young, Dorothy lived across the street from the Simmons family and she and Curt went to school together from the first grade. “I was shy,” Simmons said. “We never started dating until after I was out of high school.” They were married on September 23, 1951. The couple raised two sons, Timothy and Thomas, and a daughter, Susan. Curt and Dorothy celebrated their 60th wedding anniversary in 2011.

In 1968 Simmons was inducted into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame. In 1993 he was made part of the Philadelphia Baseball Wall of Fame, with a plaque in Citizens Bank Park. In 1997 Simmons was inducted into the Brooklyn Dodgers Hall of Fame in the outstanding opponent category. In November 2011 he was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame.

He died at the age of 93 on December 13, 2022.

Sources

Interviews with Curt Simmons conducted by the author in March 2009 and September 2011

“What Ever Became of … Curt Simmons.” Baseball Digest, March 1970

Furman Bisher. “Hank Aaron Tells a Secret.” Baseball Digest, November 1971

Bob Broeg. “Season’s Biggest Dollar’s Worth.” Baseball Digest, November 1962

Howard Bryant. The Last Hero: A Life of Henry Aaron (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010)

Skip Clayton and Jeff Moeller. 50 Phabulous Phillies (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing Inc., 2000)

Frank Eck. “Simmons’ Feet Get Twisted Up.” Baseball Digest June 1948.

David Halberstam. October, 1964 (New York: Villard Books, 1994)

Jane Leavy. The Last Boy: Mickey Mantle. (New York: HarperCollins, 2010)

Ed Linn. “The Tragedy of the Phillies,” in The Phillies Reader (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2005), 104-121.

Robin Roberts and C. Paul Rogers, III. The Whiz Kids and the 1950 Pennant (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996)

Robin Roberts. My Life in Baseball. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2003)

C. Paul Rogers, III. “The Day the Phillies Went to Egypt,” in Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2010.

Lyle Spatz, editor. The SABR Baseball List & Record Book (New York: Scribner, 2007)

Carson VanLindt. Fire and Spirit: The Story of the 1950 Phillies (New York: Matabou Publishing, 1998)

Notes

1 Data in C. Paul Rogers, III, “The Day the Phillies Went to Egypt.” Baseball Research Journal (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2010), 9-12. Some of the games may have been shortened by a mercy rule, hence the unusually low number of innings.

Full Name

Curtis Thomas Simmons

Born

May 19, 1929 at Egypt, PA (USA)

Died

December 13, 2022 at Ambler, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.