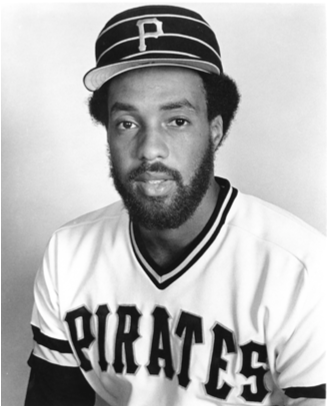

Doe Boyland

Dorian “Doe” Boyland was a good prospect who never got a proper chance to show what he could do in the major leagues. The first baseman received three trials with the Pittsburgh Pirates — in 1978, 1979, and 1981. He got into a total of 21 games, but started none of them and played in the field in just one — all his other opportunities came as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. He got just two singles and a walk in 20 plate appearances.

For a time Boyland was touted as the heir to the great Willie Stargell in Pittsburgh. He wasn’t a big power hitter — the most home runs he ever had in any season was 14 — but he hit for good average and stole an unusual number of bases for his size (6-feet-4 and 200 pounds) and position. He worked hard to become adept in the field — he had never played first base before turning professional. Yet even after Stargell entered his twilight as a player, the Pirates used other veterans instead. Boyland finally got a change of scenery in 1982, but could not break through in the San Francisco Giants organization either. He retired from pro baseball after that season.

Boyland then went on to huge success as a businessman. He founded his company, Boyland Auto Group, in 1987 and led it to the number-4 ranking on Black Enterprise’s auto dealers list for 2013. Brainpower, charisma, and determination were all big ingredients — yet he also gave credit to what he learned as a member of the 1979 World Series champion Pirates, especially from manager Chuck Tanner. In a 2011 promotional video, Boyland said, “I was very fortunate to be involved with the 1979 Pittsburgh Pirates. … I’ve got the [World Series] ring on right now. That was a dream in itself. I still get asked today, ‘How was it?’

“But the one thing that was very helpful, in terms of not just making money, and people respecting what I’ve done, and having arrived as a baseball player … Chuck Tanner was the eternal optimist. He could motivate a guy that was tired, hurt, injured, didn’t feel like playing, to run through a brick wall. And not knowing at the time, I was picking all of that stuff up. So by the time it came that I was in the automobile industry and became a manager, I understood what motivation was all about.”1

Dorian Scott Boyland was born on January 6, 1955, in Chicago. His parents were William and Alice (née Walker) Boyland.2 He had one sibling, an older sister named Brenda. William and Alice were divorced when little Dorian was around 4 years old.3 Alice, who worked as an accountant for retailer Montgomery Ward, then brought both children up by herself. She was a heroine to her son.4

In pursuit of better education for her children, Alice moved the family to the South Shore neighborhood of Chicago in 1962.5 Dorian attended Isabelle O’Keeffe Elementary School and South Shore High, and his drive was evident from an early age. “As I was growing up, the only motivation I really had, that I could recall, was that I always wanted to do the right things. I wanted to get straight A’s, I wanted to be the fastest guy in kickball, I wanted to be the last person out in dodgeball, I wanted my mom to say, ‘Good job.’ I wanted to be the best at whatever I was trying to accomplish.”6

At one time in his youth, though, Boyland joined a gang. He talked about it with a group of 250 Chicago youngsters in 2010. “Seeing he was headed for trouble, his single mother sent him away to live with his grandmother. ‘I learned a lot that summer, came back and made a different choice.’”7 Throughout his life, this man never touched alcohol, tobacco, drugs, or even coffee.

Boyland won a scholarship to the University of Wisconsin at Oshkosh. His first love was basketball, and he later said that he chose UW-Oshkosh because of the head basketball coach, Robert White. In 2011 he called Coach White “a pioneer in recruiting minority players and diversifying the team,” and talked of how the coach and his wife were another pair of parents to him.8

“Oshkosh had a good baseball team too,” wrote Pittsburgh Press columnist Dan Donovan in 1978, “and since Boyland threw the ball pretty well, he volunteered to pitch.” He had a strong freshman year on the mound, helping the Titans get to the 1973 NAIA College World Series.9 One of his teammates was Jim Gantner, who went on to play 17 seasons in the majors with the Milwaukee Brewers. “The scouts came out to see him, and so they saw me too,” said Boyland.10

Knee surgery after a basketball injury changed his priorities. “I lost some quickness,” Boyland said. “I knew if I was going anywhere in sports, it would have to be in baseball.”11

Over time in college, Boyland’s bat got him into the everyday lineup. When he was not pitching, he played designated hitter and (on occasion) the outfield. As a senior in 1976, though his pitching record was so-so, Dorian was 29-for-95 (.305) with 6 homers and 26 RBIs.12 Major-league scouting directors and coordinators named him to the second team of The Sporting News College All-America squad in 1976.13

That June Pittsburgh chose Boyland in the second round of the amateur draft. “I was not really surprised about being picked in the second round,” he said, “because scouts had told me that I would be going in the first three rounds, and I had been contacted by the Pirates’ chief scout [future general manager Harding “Pete” Peterson] this summer.”14

Howie Haak, the Pirates’ superscout, was surprised that Boyland was still available. He later said, “We knew he could run, and he had a good arm. We’ve found that most natural athletes can learn to hit. If they can’t, you send them home.”15

“I am really glad to be with the Pirates,” Boyland also said, “because they like my hitting. They haven’t said too much about pitching, because as a pitcher I would only get to bat every fourth day and they seem to want my bat in the order every day.” The Oshkosh baseball coach, Russ Tiedemann, said, “Dorian is not a good cold-weather pitcher and pitching in Wisconsin in the spring has not been real good to him. He does have all the tools to make it in the big leagues, though.”16

Murray Cook, then Pittsburgh’s assistant farm director, liked Boyland’s overall baseball abilities. “We think he is the type of player that can help us to a pennant. We just feel this way but have no guarantees. We do know he has the size, agility, and coordination of a baseball player. Boyland is also an outstanding runner with fine speed and an adequate arm, so he has the tools we look for. We want him to play every day at this point and do not plan on using him as a pitcher.”17

Boyland reported to Salem (Virginia) of the Carolina League (Class A), where he was made a first baseman, though he had never played there before. “That was my plight,” he said. He was thrown in the deep end, with no instruction, and expected to cope. “I got there and the manager, Steve Demeter, told me, ‘You’re batting fourth and playing first base.”18

“I didn’t know how to field the ball at first base,” he said in 1978. “And when I picked it up, I didn’t know how to throw it. I looked pretty silly. I never knew there was so much involved in playing baseball.”19 He later added, “It really made me depressed.”20 In 71 total games, Boyland hit .269 with 3 homers and 31 RBIs. “I was hitting a buck-twenty or a buck-forty early on. If I hadn’t been a second-round pick, they would probably have released me.”21

Nonetheless, Boyland was invited to practice with the big leaguers in spring training 1977.22 He stepped up to Double-A and hit very well for Shreveport in the Texas League: .330-11-60 in 119 games. He also stole 30 bases and got caught just six times. The first-base position belonged to him — even though, in his own words, “I still couldn’t catch a cold there.” (He committed 28 errors.)23

In the fall of 1977, the Pirates and New York Yankees fielded a combined entry in the Florida Instructional League.24 “I was finally taught how to play first base — by the Yankees. Ed Napoleon took me out and put me through all kinds of drills. I learned how to grip the ball so it wouldn’t move like it did when I was a pitcher. Gene Michael helped too.” According to Boyland, the Yankees were interested in acquiring him (that December they lost Willie Upshaw to the Toronto Blue Jays in the Rule 5 draft).25

Shortly after that, Boyland gained his first experience in winter ball. He joined Navegantes del Magallanes in the Venezuelan league. He got into 28 of the 70 games that season, because 34-year-old veteran Bob Oliver (the first baseman at Triple-A Columbus that year) was also with the Navigators. In just 98 at-bats, though, Boyland hit well: 5 homers, 24 RBIs, and a .337 average. One of his managers that season was Pirates first-base coach Alex “Al” Monchak. A number of other Pirates prospects were there too, such as pitchers Rod Scurry and Fred Breining, and infielder Gary Hargis. When asked about his experience in Venezuela, Boyland responded enthusiastically. “I loved it, loved it. I didn’t stay in a hotel, I stayed with the people because I wanted to improve my Spanish. Still to this day it’s one of my favorite places.”26

Boyland was again invited to work out with the Pirates in the spring of 1978. “Remember the name: Dorian Boyland,” said beat writer Charley Feeney, mentioning for perhaps the first time that the young man was someday expected to replace Willie Stargell.27 Stargell himself said, “You can see he’s going to hit for a good average. He’s got strong, quick wrists.” But Dorian said, “I want to be [a] complete first baseman. … I want to bunt, steal bases, and hit for average as well as show power. I also want to be a good first baseman defensively.”28

Boyland moved up to Triple-A Columbus of the International League for the 1978 season — Bob Oliver was out of the Pirates organization — and had another good year (.291-12-61 in 113 games). He was rewarded with his first call-up to the majors that September.

His debut was bizarre and unique. During the first game of a doubleheader on September 4 at Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Stadium, Chuck Tanner sent Boyland in to pinch-hit for pitcher Ed Whitson. The score was tied 4-4 against the New York Mets with one out in the seventh inning, and Phil Garner was on first base. Pitcher Skip Lockwood had a 1-and-2 count on Boyland, but Lockwood had to come out of the game with a sore shoulder. Mets manager Joe Torre brought in a southpaw, Kevin Kobel, and Tanner sent righty Rennie Stennett in to hit for the lefty Boyland. Stennett promptly took strike three; by the rules, the strikeout was charged to Boyland.29

“For many years I dreamed of what I might do in my first major-league at-bat,” Boyland said. “I dreamed of hitting a grand-slam homer and even of striking out, but I never thought I’d strike out — and be watching from the dugout.”30

Sixteen days later, Boyland got his first base hit in the majors. It came at Wrigley Field in Chicago, playing for the first time in his hometown in a major-league uniform, with his mother, sister, and around 100 friends in the crowd.31 Tanner then put the steal on, although Pittsburgh was trailing 4-1 in the eighth inning. He kept it on, even though Frank Taveras fouled off four straight pitches. On the fifth attempt, Taveras lifted a short fly that Boyland thought was catchable, but Cubs shortstop Iván de Jesús didn’t get to it. Doe headed for third base, but “‘I missed second,’ he said. ‘I knew I missed it. I hoped they [the umpires] wouldn’t notice. Manny Trillo called for the ball and appealed. They proved me wrong.’”32

Boyland’s lone outing in the field as a big leaguer came at Three Rivers on the last day of the season. Willie Stargell — batting leadoff for one of just 15 times in his 21 years as a Pirate — opened the bottom of the first with a single. Boyland came in to run for him and played first base the rest of the way, getting his only RBI in the majors with his only other hit.

Boyland returned to Venezuela for the winter of 1978-79. He was not as successful this time (.268-0-18 in 30 games) and had to leave early after sustaining a wrist injury.33 That problem wasn’t serious, but a recurring hamstring problem plagued him in 1979. In spring training, the Pirates wanted Boyland to work in left field, since Stargell (who became the NL’s co-MVP that season) was still the main man at first base. “A ball was going down the line and I broke for it. I felt something in my leg,” Boyland recalled in 1980. He sat out the rest of spring training and was sent down to the Pirates’ new Triple-A team, the Portland Beavers of the Pacific Coast League.34

“I’d finally become a real first baseman, and what happened? They sent me back to the outfield,” said Boyland. “But here’s my demise. When the Pirates sent me down, I was distraught. I said some unkind words to Chuck Tanner.”35

With Portland, Boyland remained in left field — and pulled the hamstring again in his first game. He was out for a month, played again, and was hurt again.36 All told, Boyland played in just 30 games for the Beavers, hitting just .245-2-12 in 102 at-bats.

Even so, when the rosters expanded that September, Boyland went back up to Pittsburgh. He pinch-hit three times, striking out twice, and also pinch-ran once. He was not eligible for the Pirates’ successful postseason; he was one of the eight players who received a modest $250 cash grant when the team voted on World Series shares.

His leg did not bother Boyland while he was with Pittsburgh, but during winter ball in the Dominican Republic with Águilas Cibaeñas, the problem recurred after an opposing first baseman tripped him. “Now he has to prove he can play again,” said Howie Haak.37

In the spring of 1980, the new heir apparent to Stargell at first base was a big Puerto Rican named Eddie Vargas. Vargas (who made the majors briefly with the Pirates in 1982 and 1984) was coming off a strong year in Single A and was headed for Double A. He was also four years younger than Boyland. “This year in spring training I’m more realistic,” said Boyland. “I know I would only make the team in the event of a trade or an injury. If I don’t make the team, I’ll set my goals very high. If I have a good season in Portland, I can make the team next year or maybe someone else will want me.”38

A little over a week later, the subject arose of what would happen if Stargell got hurt. Boyland responded, “It all depends on how serious an injury and how everybody else on the team is doing and the extent of the injury. Then they might say, ‘Get Doe Boyland up here.’”39 As it turned out, “Pops” was able to play in just 67 games in 1980 — but Pittsburgh used John Milner and Bill Robinson at first base that year. Bill Madlock, Manny Sanguillen, and Kurt Bevacqua also filled in.

Meanwhile, Boyland spent the year at Portland. There had been talk that he would play left field, but he returned to first base, hitting .281-14-67 in 120 games. His leg was healthy again, as evidenced by 26 stolen bases. “And I played flawless defense,” he added. “But you know how it is — you get labeled, and that’s it.”40

Despite his good year, Boyland saw no major-league action in 1980. “Everybody thought I was going up after September 1,” he remarked the following spring, “But all I got was a plane ticket home to Chicago. And during the year I was very disappointed I didn’t get called up. I was hitting about .340 and I was leading the team in home runs and stolen bases. I got so down I went into a tremendous slump for about a month and a half. There was no one for me to talk to and I let it bother me.”41 He put it even more strongly looking back in 2014: “I was done. I was through.”

In the spring of 1981, after a winter in the Mexican Pacific League with Águilas de Mexicali, Boyland roomed with Mike Easler. “The Hit Man” knew firsthand about waiting years to get his chance to break through in the majors. “He’s helped me accept my situation a little better,” Boyland said. “Seeing what he went through to get here. … I know I just have to hang in there.”42

Yet even though Boyland was hitting well in camp, general manager Pete Peterson told him that in all likelihood he was bound for Portland again. Stargell was still on the scene — “If Willie can get to the plate in a wheelchair, he’s going to play,” Boyland said.43 Plus, shortly before the season started, Pittsburgh acquired Jason Thompson from the California Angels. Things might have turned out differently, though, had Commissioner Bowie Kuhn not prevented the Thompson trade from becoming a three-way deal with the Yankees. Jim Spencer, who had little left in the tank, would have wound up with the Pirates instead.

Boyland, who had welcomed the idea of a trade, still had confidence in his abilities. He said, “I think I can hit 20 home runs and steal 30 bases in the major leagues. That’s pretty select company.”44 During 1981, though, he was hurt again and had to share time at Portland with Craig Cacek (four months older) and Bob Beall (who was turning 33 — the Beavers roster had at least 10 players aged 30 and over that year). Boyland got into just 68 games, and though he hit .310, he had only 2 homers and 28 RBIs.

Despite his part-time status, Boyland made it back to Pittsburgh in September for the last time. He got into 11 games, going hitless with a walk in nine trips as a pinch-hitter and pinch-running twice.

Boyland played in seven games for Magallanes during the 1981-82 winter season. On December 11, 1981, he was dealt to the San Francisco Giants for veteran pitcher Tom Griffin. “I was out of options,” he recalled, “so I thought they would finally keep me. So what did they do? They traded me.”45

Boyland still held promise for at least one high authority — Frank Robinson, who was then the Giants’ manager. Robinson called him a good young prospect (though Doe was about to turn 27) and said, “I saw Boyland when I was at Rochester in 1978 and he impressed me.”46

It was much the same story with San Francisco, though. The Giants had two veteran first basemen in Enos Cabell and Dave Bergman. Then in late February 1982, they signed another veteran, switch-hitting Reggie Smith, as a free agent (the seven-time All-Star outfielder played first base only during his final season).“I remember Frank Robinson giving me the news,” said Boyland.47

Shortly thereafter, Cabell was traded, and Boyland — a nonroster player — was given a chance to stick with the big club in spring training.48 Yet Darrell Evans, who played first base a good deal, was on the team too. Boyland was ticketed for Triple-A Phoenix. There he played in 107 games, but the primary first baseman for that team was José Barrios — again, a younger player than Boyland (by two years). Boyland was in the lineup more often as a designated hitter, and his production was not high (.259-7-52 in 371 at-bats).

“I said to myself that year, ‘Better find a new job.’”49 After he quit, Boyland — with his degree in business administration and computer science — was mulling an offer from Intel Corp. to become a systems analyst. (The semiconductor company still has a major presence in Oregon.) The door to his true career then opened, though, thanks to Ron Tonkin, who was president and part-owner of the Portland Beavers — and a leading car dealer in the Portland area.

“He convinced me to come try the car business for 60 days, and if I didn’t like it, I could go back to my other position,” said Boyland in 2005. Thinking he would have a managerial position, he accepted — but when he got to the dealership, he found he was a rank-and-file salesman. Boyland added, “It was the best thing that ever happened to me.”50

When the two-month trial period was up, Tonkin made Boyland an assistant manager. Within two years, they were partners, acquiring a Dodge dealership together; Boyland held a 30 percent stake. In 1987 he bought his own dealership, and over time he built it into a chain of Dodge, Ford, Nissan, Mercedes-Benz, Honda, and Hyundai agencies.51 The jewel in the crown: Mercedes-Benz of South Orlando, which opened at a prime location in 2004. The Mercedes regional manager for the Southeast said of Boyland, “He has a knack for responding to market demands and understanding how markets change.”52 One of Boyland’s partners put it this way: “Dorian is a very driven guy with vision. … He’s got the moxie and savvy to put deals together.”53

Boyland also based his business on knowing the numbers — something that dated back to early childhood — and fiscal prudence. From the beginning, he established a core value: ensuring satisfaction for his customers, employees, and manufacturers. He felt a strong sense of duty in setting a successful example for the minority community and helping the generations that followed his.54

Boyland emphasized the importance of connections with people in his foreword to the 2014 book Networking for Black Professionals. In addition to what he called “the 3 C’s” — Competitive Edge, Confidence, and Competence — he said that talking to people daily and listening to them bred high customer satisfaction. He concluded with the encouraging words, “Don’t let fear hold you back, take the ride and see where it leads you!”55

Boyland said he often saw players he faced — “Manny Trillo was just in the store last week” — and comrades from the 1979 Pirates. For example, “Lee Lacy was just here. Dave Parker comes down all the time.”56 Though his stay in the big leagues was brief, Dorian Boyland cherishes the many friendships he formed during his baseball career.

Grateful acknowledgment to Dorian Boyland for his memories (telephone interviews, May 5 and May 7, 2014) and to his sister Brenda Mitchell for the introduction.

Sources

Internet resources

purapelota.com (Venezuelan statistics).

blackenterprise.com.

Notes

1 Boyland Auto Group — “Ride with a Winner” promotional video, 2011 (youtube.com/watch?v=fg2zO783P0c).

2 Who’s Who Among African-Americans (Farmington, Michigan: Gale Group, 2002), 126. This reference gave Alice’s maiden name as Jones, but according to her daughter, Brenda, it was Walker.

3 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 7, 2014.

4 Lucia Reid, “The Midas Touch,” Onyx (Orlando, Florida), July-August 2007, 23.

5 Reid, “The Midas Touch,” 22.

6 “Ride with a Winner.”

7 Maudlyne Ihejirika, “Success ‘up to you,’ teens told,” Chicago Sun-Times, May 8, 2010.

8 “Coach White to be honored at men’s basketball reunion,” UW Oshkosh Today website, August 10, 2011.

9 The NAIA’s freshman eligibility rules are different from those of other associations, such as the NCAA.

10 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

11 Dan Donovan, “Baskets to Bases: Boyland a Natural,” Pittsburgh Press, March 2, 1978: A-7.

12 Dave Grey, “Boyland, Pascarella are high draft picks,” The Daily Northwestern, (Neenah/Menasha, Wisconsin), June 9, 1976: 9.

13 Lou Pavlovich, “Bannister Chosen Player of Year on All-America Team,” The Sporting News, July 31, 1976: 28.

14 Grey, “Boyland, Pascarella are high draft picks.”

15 Donovan, “Baskets to Bases: Boyland a Natural.”

16 Grey, “Boyland, Pascarella are high draft picks.”

17 Ibid.

18 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

19 Donovan, “Baskets to Bases: Boyland a Natural.”

20 Glenn Miller, “Waiting and Hoping,” St. Petersburg Independent, March 20, 1980, 1-C.

21 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

22 Charley Feeney, “Bucs’ Key Player: Versatile Robinson,” The Sporting News, January 29, 1977: 46.

23 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

24 Don Greenberg, “He can go all the way — with experience,” St. Petersburg Times, September 27, 1977: 4. Subject: Joe Lefebvre.

25 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

26 Telephone interviews, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5 and May 7, 2014.

27 Charley Feeney, “Bucs to Lean Heavily on Toughy Duffy,” The Sporting News, February 18, 1978: 50.

28 Donovan, “Baskets to Bases: Boyland a Natural.”

29 Charley Feeney, “Pirates Trail by One After Sweep of Mets,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, September 5, 1978: 13. This article says that Stennett swung and missed, but Boyland remembered that Rennie was caught looking.

30 Jerome Holtzman, “Some Free Advice,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1978: 42.

31 Reid, “The Midas Touch,” 23.

32 Miller, “Waiting and Hoping.”

33 Dan Donovan, “Candelaria, Stennett Find Cure for Ailments in Winter Baseball,” Pittsburgh Press, January 14, 1979: D-8.

34 Dan Donovan, “Another Turning Point for Boyland,” Pittsburgh Press, March 11, 1980: D-1.

35 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

36 “Another Turning Point for Boyland.”

37 Donovan, “Another Turning Point for Boyland.”

38 Donovan, “Another Turning Point for Boyland.”

39 Miller, “Waiting and Hoping.”

40 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

41 Ron Cook, “Boyland weary of waiting to be Willie,” Beaver County (Pennsylvania) Times, March 16, 1981: B1.

42 Ibid.

43 Dan Donovan, “Boyland Claims His Future Is Now,” Pittsburgh Press, March 16, 1981, C-1.

44 Ibid.

45 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

46 Nick Peters, “Giants Under Fire for Peddling Griffin,” The Sporting News, January 2, 1982: 41.

47 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

48 Nick Peters, “Robinson, Players Big on Confidence,” The Sporting News, March 6, 1982: 36.

49 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

50 Christina Hildreth, “Grand slam performer,” Orlando Business Journal, July 25, 2005.

51 Alan Hughes, “The Game Plan,” Black Enterprise, April 1, 2012.

52 Hildreth, “Grand slam performer.”

53 Hughes, “The Game Plan.”

54 Reid, “The Midas Touch,” 24-25. Ihejirika, “Success ‘up to you,’ teens told.” Alan Hughes, “8 Steps to Keep Your Small Business on the Road to Success,” Black Enterprise, March 25, 2013.

55 N. Renee Thompson, Michael Lawrence Faulkner, and Andrea Nierenberg, Networking for Black Professionals (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Education, Inc., 2014), vii-viii.

56 Telephone interview, Dorian Boyland with Rory Costello, May 5, 2014.

Full Name

Dorian Scott Boyland

Born

January 6, 1955 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.