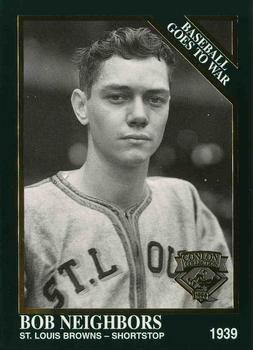

Bob Neighbors

In the baseball record books, Bob Neighbors was originally without a date of death but a “date of loss.” Now, most have the August 8, 1952, date of death but provide no indication of where he died. For books or sites that offer information on the place of burial or cremation, there is often a notation such as “MIA” or “body not recovered.” Neighbors had a brief stint in the majors with the St. Louis Browns, then went off to war like many ballplayers of his generation. Unlike almost every one of his ball-field colleagues, he decided to make military service his career. There’s no guarantee how long he might have lived had he not, but in the end the decision to stay in the Air Force cost him his life.

In the baseball record books, Bob Neighbors was originally without a date of death but a “date of loss.” Now, most have the August 8, 1952, date of death but provide no indication of where he died. For books or sites that offer information on the place of burial or cremation, there is often a notation such as “MIA” or “body not recovered.” Neighbors had a brief stint in the majors with the St. Louis Browns, then went off to war like many ballplayers of his generation. Unlike almost every one of his ball-field colleagues, he decided to make military service his career. There’s no guarantee how long he might have lived had he not, but in the end the decision to stay in the Air Force cost him his life.

Only one major-league ballplayer was killed in the Korean War. Ted Williams’ jet was hit during a dive-bombing run over North Korea, and he was extremely lucky to survive a crash-landing. Jerry Coleman (who had fought in World War II as well) also survived intense ground fire and the crash of his own aircraft on another mission. Others served, but Robert Otis Neighbors was the only major leaguer who made the ultimate sacrifice.

Neighbors played in 1939 (just seven major-league games, debuting on September 16) for the Browns. That was it. Two hits in 11 at-bats. A batting average of .182. Three runs scored. One RBI – a solo home run. With half of his hits being homers, he has a .455 slugging percentage. In the field, the 5-foot, 11-inch, 165-pound right-handed shortstop had 12 chances and converted 11 of them; the one error leaves him with a career fielding percentage of .917.

Perhaps he could have come back to the majors after his brief stint. He did play two more years in the minor leagues, 1939 and 1940, but after December 7, 1941, the world changed for many Americans.

Neighbors hailed from Oklahoma. He was born on November 9, 1917, in Talihina, in the southeastern part of the state, near Arkansas, just 10 years after the Oklahoma Territory became one of the United States. Talihina was a Native American community, but the Neighbors family had only a little Indian blood. Bob’s brother Morris, two years younger, estimated that he and Bob were one-sixty-fourth Cherokee.

The family moved from Talihina to Osage County, in the northern part of the state near Kansas, where three younger sons were born. They had lost a boy before Robert was born. The schools in the area were rural county schools, without such features as gyms. They played basketball on outdoor courts, and what other sports they could. Bob attended the Wild Horse elementary and high school at Hominy, and one year at Oklahoma Baptist University. “Bob was always good at sports,” said another brother, Carl. “Played a lot of softball, too. There was an older fellow who worked for Shell Oil Company. His name was Bill Crockett and he worked with the Chicago White Sox. He wasn’t necessarily a scout but he moved into the community, started playing, and just took notice of Bobby and thought he had some potential. He took a liking to him and he got a tryout at Siloam Springs, Arkansas – Class D ball at that time.”

Bob may have inherited some of his talent from his father. Carl said, “Dad was quite small in stature but he played one of the best brands of sandlot baseball in the county back then.” Their father, Leither Neighbors, came from Mina, Arkansas, but found work as a ranch hand and then in the oilfields, where he became a pumper and a head roustabout. He and his wife Nellie, a native Oklahoman, had raised their children “on good Christian principles,” stressed Carl. “Dad was looked up to in the community and he helped a lot of people out. He never denied a handout to anybody who needed one despite the fact that we, too, were as poor as dirt – we just didn’t realize it at the time.”1 Morris added that their dad had organized a number of local youth baseball teams in the days before there was Little League.

Carl was good enough to merit a brief look pitching with Palestine in the East Texas League. “I tried, but I flubbed. I pitched on a little team here in Tulsa. Somebody said I ought to try out. Of course, you didn’t have much coaching or training back then. You just kind of had to take it cold turkey. I think I got into three games, but I just didn’t have it.” Morris played some baseball as a walk-on at Oklahoma A&M, which he attended on the GI Bill after World War II, a third baseman. He did some coaching after college and played some semipro ball for Woodward, Oklahoma. He made it to the national semipro tournament in Wichita for Woodward, and another time for Ashland.

But Bob was the best ballplayer in the family. He made the trip to Siloam Springs in 1936 and made the team as a shortstop – despite never having played a full game of baseball. Neighbors wrote on his National Association Contract card in 1937, “I had been playing softball, but had always wished to play baseball. I went to Siloam Springs, to try out, and made the team. I played my first complete game of baseball at Siloam, At Siloam is where I became a pro in baseball.”2 In 1936, his player index card (the National Association contract card) shows him with Siloam Springs and El Dorado.

The Siloam Springs Travelers were in the six-team Arkansas-Missouri League, affiliated with the Cincinnati Reds, and they led the league that year, winning the playoffs over the Cassville Blues. Bob played with them two seasons (the Travelers finished third in 1937), and played well, hitting .279 with 16 home runs his first year and .286 with 8 home runs the second. In 1937, he also played in 14 games with the Abbeville Aces in the Evangeline League, another Class D team. Siloam Springs became a St. Louis Browns affiliate by the 1938 season.

In 1938, he played a full 139 games with the Palestine Pals, another Browns affiliate in the Class C East Texas League. The team didn’t do so well, finishing seventh among eight teams, but Bob batted .301 with 18 homers even after moving up to the higher classification.

The Browns trained, perhaps appropriately, in Brownsville, Texas, and Bob was invited to spring training in 1939, battling it out with Vern Stephens for the shortstop position. Bob won that round; his play in 1938 and in the spring advanced him up the Browns ladder to the Class B Three-I League, where he played short for the Springfield Browns, making the league All-Star team despite a .269 average at the plate. Springfield finished fourth, but won the league playoffs. At the very end of the 1939 season, Bob got the call to the major leagues and he made his debut on September 16. Don Heffner was the team’s main shortstop, with Mark Christman playing often and backup work contributed by Red Kress and Sig Gryska, but Bob got into seven games. The Browns were in last place.

On the 16th, Christman was playing short, but he was pinch-hit for in the eighth inning and Neighbors played shortstop in the bottom of the eighth, making one putout but not getting to the plate. His first start came against the Boston Red Sox on September 20. He batted eighth in the order. It became a 16-inning game, but after he went 0-for-3, manager Fred Haney tried to get something going and pinch-hit for him. It took all 16 innings, but the Browns won the game.

Bob collected his first hit the next day, going 1-for-3, and it was a home run off Red Sox starter Denny Galehouse. Only 598 paying customers saw it, but it happened – a seventh-inning drive right down the left-field line into the net above Fenway Park’s left-field wall. It landed about halfway up the net, and was fair by about five feet. The attendance was believed to be the all-time low at the time. Bob’s fellow rookie Ted Williams was 0-for-4 for the Red Sox. Neighbors and Browns pitcher Jack Kramer each had their first career homers, but they were the only two Browns runs and Boston won, 6-2.

Neither of Neighbors’ brothers ever saw him play with St. Louis. In 1940, he was placed with the Toledo Mud Hens (American Association), the Browns’ Double-A club. He appeared in 71 games (but played in the field in only 36) and batted .279. He also appeared in four games for San Antonio, with just one hit in 14 at-bats, losing most of the season to an attack of appendicitis and subsequent surgery.

There was one more year in baseball, a full 1941 season in San Antonio with the Missions. In February, Bob married Winnifred Willcox, but lost her six months later – during the baseball season – when she was run over and killed by an automobile driven by a 16-year-old boy in Oklahoma City. Morris said that for years Bob was troubled with the feeling that if he’d been in another profession than baseball he would have likely been closer to home and the accident might not have happened. “I really do think that after Winnie was killed, Bob just lost his desire,” he said.3

Neighbors played in 155 games for San Antonio, but hit only .216 in 496 at-bats. It’s not clear he had a future in baseball. Bob’s brother Carl summed up his work in five words: “Good glove, not much bat.” One is tempted to argue with the fielding appraisal, though. He committed 45 errors in 1941 for a .941 fielding percentage. It was the fourth season he’d committed more than 40 miscues. Despite what today looks like a poor fielding percentage, the quality of both infields and groundskeeping prior to the post-WWII period was usually much lower than today, and official scoring regarding errors was much stricter. Neighbors was considered a good fielding shortstop, and researcher Gary Gillette notes that in 1941, his fielding percentage was the highest in the Texas League, and his raw range factor was also the best by a large margin.

After the Japanese attack on the United States Navy at Pearl Harbor, Bob was one of many who enlisted in the armed forces. He went to Wichita and signed up for the Army Air Forces in March 1942, the first of the four Neighbors brothers to sign up. Bob flew some out of Italy in the European Theater, but wound up in the Pacific, and had become quite an accomplished pilot, it seems. Chuck Stevens, a teammate on the Springfield Browns, recalls being on Tinian in the Marianas. “A guy walked up to me and I didn’t believe my eyes. It was Bob Neighbors. He was (General Barney Giles’s) pilot. Giles was out there visiting our generals, and Neighbors was Giles’ left-seat pilot. He was a captain when I saw him. Obviously a hell of a pilot or he wouldn’t be flying a general.”

World War II took a toll on the Neighbors family. Carl served in the Merchant Marine and made 10 trans-Atlantic crossings in convoy, worried about German submarine attacks. Morris was a radar man second class in the Navy serving on the destroyer Leutze when it was hit by Japanese kamikaze planes. It was on April 6, 1945, and the Leutze was in a picket line about 50 miles from Okinawa. The Japanese launched about 350 airplanes, some 25 of which attacked the pickets. The destroyer Newcomb was hit three times, and the Leutze came up alongside to try to help douse the fires on the ship. Morris left his work in the radar room to help man a fire hose. A kamikaze bearing a 500-pound bomb hit the Newcomb, skidded across it, and slammed into the Leutze, tearing a 40-by-10-foot hole. Some were killed; Morris was knocked unconscious and awoke with a concussion, two badly sprained ankles, and numerous abrasions. The Leutze limped back to San Francisco for repairs, but the ship was too badly damaged and, since the war was nearly over, it was stricken from the Navy list. Morris was among those awarded the Purple Heart.

Morris was fortunate to survive. On April 24, just 18 days after the Leutze was hit, the youngest Neighbors boy did not survive an attack on his vessel. Paul M. Neighbors was a coxswain in the Navy, serving aboard the destroyer escort Frederick C. Davis, doing coastal duty off Newfoundland, where a number of German U-boats were operating. As the Navy vessels began to close in on a nest of Nazi submarines, one U-boat fired a torpedo that hit the forward port side of the Davis. Within five minutes, the ship had snapped in half and went down with 115 lives lost. Neighbors was among them. Other escorts sank the German sub later that same day.

Sometime during the war, Bob decided he would stay in the service, according to his brothers Morris and Carl. “He dearly loved the Air Force duty and the new way of life that it opened up for him,” Morris said. After the war, Bob returned from the Pacific and was stationed at Maxwell Field in Montgomery, Alabama. He was remarried in Montgomery, to Kathleen Burke, and they had a son, Robert Cameron Neighbors. Bob managed a service baseball team at Maxwell Field, which traveled all over the United States playing at various tournaments.

Air Force Major Robert Otis Neighbors, service number 12406A, joined the 13th Bomb Squadron of the Third Bombardment Wing during the Korean War and flew a B-26 Invader, a speedy attack bomber with a three-man crew. The squadron, whose missions took place mostly at night, was nicknamed “The Grim Reapers.” Stationed at Kunsan Air Base, Korea, on August 8, 1952, he and his crew volunteered to take on an extra mission, according to Morris Neighbors: “The pilot of the plane became ill, and (Bob) and his whole crew took the other flight instead. It was supposed to be a milk run, but they ran into some anti-aircraft fire where there hadn’t been any before.”

It’s unlikely the mission was truly seen as a milk run; this was an intense time and four crew members from the squadron had been lost the very day before, August 7, when their B-26 was hit by ground fire near Hwangju, attempted a landing, and crashed into a dike. On August 10, two days after the Neighbors mission, another B-26 from the squadron was hit in the right fuel tank and downed. The month before, on July 25, another B-26 had gone down between Pyongyang and Haeju.

On August 8, flying their B-26, tail number 44-34698, were Major Neighbors, 1st Lieutenant William L. Holcom, navigator, and Staff Sergeant Grady M. Weeks, the gunner.

The Sporting News wrote that the plane was on a bombing mission and had hit its first target, but trouble developed en route to the second target.4

The mission departed at night, as did all the missions of the Grim Reapers. At 2130 hours, the crew radioed that they had been hit. The Loss Incident Report was as concise as could be: “Circumstances of Loss: Last contact 2130L, hit, crew reported bailing out.” Their precise location was unknown. None of the three men was ever heard from again.

As noted above, the squadron had lost three B-26s in a four-day period, with 10 crew members in all (two crew members from the mission on August 10 were later repatriated in a prisoner exchange, but the other eight were lost forever). The losses prompted Lt. Gen. Glenn O. Barcus to suspend operational missions. A postwar book said, “He believed that the crews were not experienced enough in low-altitude night operations and placed a 4,000-foot restriction below which the crews could not fly during an attack mission. Following a training period and a change in command, the 3rd Bombardment Wing returned to an operational status, and did not lose a crew until December 1952.”5

On the day Bob Neighbors went down, Ted Williams was at Cherry Point, North Carolina, beginning to train on jets. He’d started in late July, and went out for his first flight with the F9F Panther on August 25. Jerry Coleman was also still stateside, training for combat in Korea. In baseball, the White Sox gave the South Side fans a treat by beating the Tigers twice, 4-3 and 2-1. The Cubs fell in Pittsburgh, 1-0, in 10 innings, one of three extra-inning games played on August 8. The Dodgers beat the Phillies, 6-3 in 10. The Boston Braves shut out the New York Giants, 2-0. The Cards fell to Cincinnati, 8-5. The Browns, Bob’s old team, broke out to a 6-0 lead over Bob Feller in the very first inning. They held a 9-6 lead over the Indians after eight full innings. Cleveland’s Larry Doby tied up the score in the top of the ninth with a three-run homer. The game went into extra innings, until the Tribe rookie Bill Glynn hit a solo homer in the top of the 12th. The Browns couldn’t score, and Cleveland won, 10-9.

Morris Neighbors talked about how his parents reacted when they learned that Bob had been shot down: “My folks, they took it pretty well. They were a class act. Back then, most families experience some kind of loss. What made it hard for my folks, neither of my brothers’ bodies were ever found.” Bob was listed as missing. When he was not found among the prisoners of war repatriated six months after the war was called off, he was officially declared as dead on December 31, 1953. Bob’s parents corresponded with the families of the other two men who were lost.

Kathleen Neighbors remarried, to a lieutenant colonel named Ed Fels who adopted Cameron. Cam Fels grew up to become an Air Force man himself.

Two days after Neighbors debuted with the Browns, Elmer Gedeon played in his first major-league game, for the Washington Senators. He appeared in five games, batting .200, and was one of two major leaguers killed during World War II, losing his life on April 20, 1944, over St. Pol, France, when his bomber was shot down. Gedeon was born seven months before Neighbors, in April 1917. The other former major leaguer killed in the Second World War was Harry O’Neill, born one month after Gedeon. He was killed on Iwo Jima, on March 6, 1945. O’Neill had also debuted in 1939, on July 23 for the Philadelphia Athletics, but appeared in only one big-league game, a late-inning replacement at catcher in a lost-cause game as the Tigers beat Philadelphia, 16-3. He’d never played in the minors, and he never had an at-bat, but he did have his moment in a major league game.

On June 14, 2000, Commissioner of Baseball Bud Selig placed a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknowns at Arlington National Cemetery. With his eyes on Cam Fels, Selig said, “Major Neighbors hailed from a family that embodied the admirable ethic of service to country. Cam, I thank you for all that you, your father, and your family have done for your country.”6

Bob Neighbors remains the only major-league baseball player to have been killed in action since World War II.

Sources

Interviews with Carl G. Neighbors on August 8 and 20, 2004, and Morris Neighbors on September 6, 2004, plus follow-up e-mail correspondence with Morris Neighbors.

Ronnie Joyner, “Bob Neighbors.” Pop Flies, Fall 2004.

Tim Rives, “Bob Neighbors – In Memoriam,” Proceedings, Center for the Study of the Korean War, Independence, Missouri, Vol. 3, No. 1, April 2003.

Interview with Chuck Stevens, December 1, 2008.

Photo credit

Bob Neighbors, Trading Card Database.

Notes

1 Quoted in Ronnie Joyner, “Bob Neighbors,” Pop Flies, Fall 2004.

2 Joyner, Pop Flies.

3 Joyner, Pop Flies.

4 The Sporting News, September 3, 1952.

5 History, 3BW, Jul-Dec 52, 3; Robert F. Furtrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-1953 (United States Government Printing Office, 1997), 520; A. Timothy Warnock, The USAF in Korea: A Chronology (Air University Press, 2000), 71.

6 Joyner, Pop Flies.

Full Name

Robert Otis Neighbors

Born

November 9, 1917 at Talihina, OK (USA)

Died

August 8, 1952 at ---, (North Korea)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.