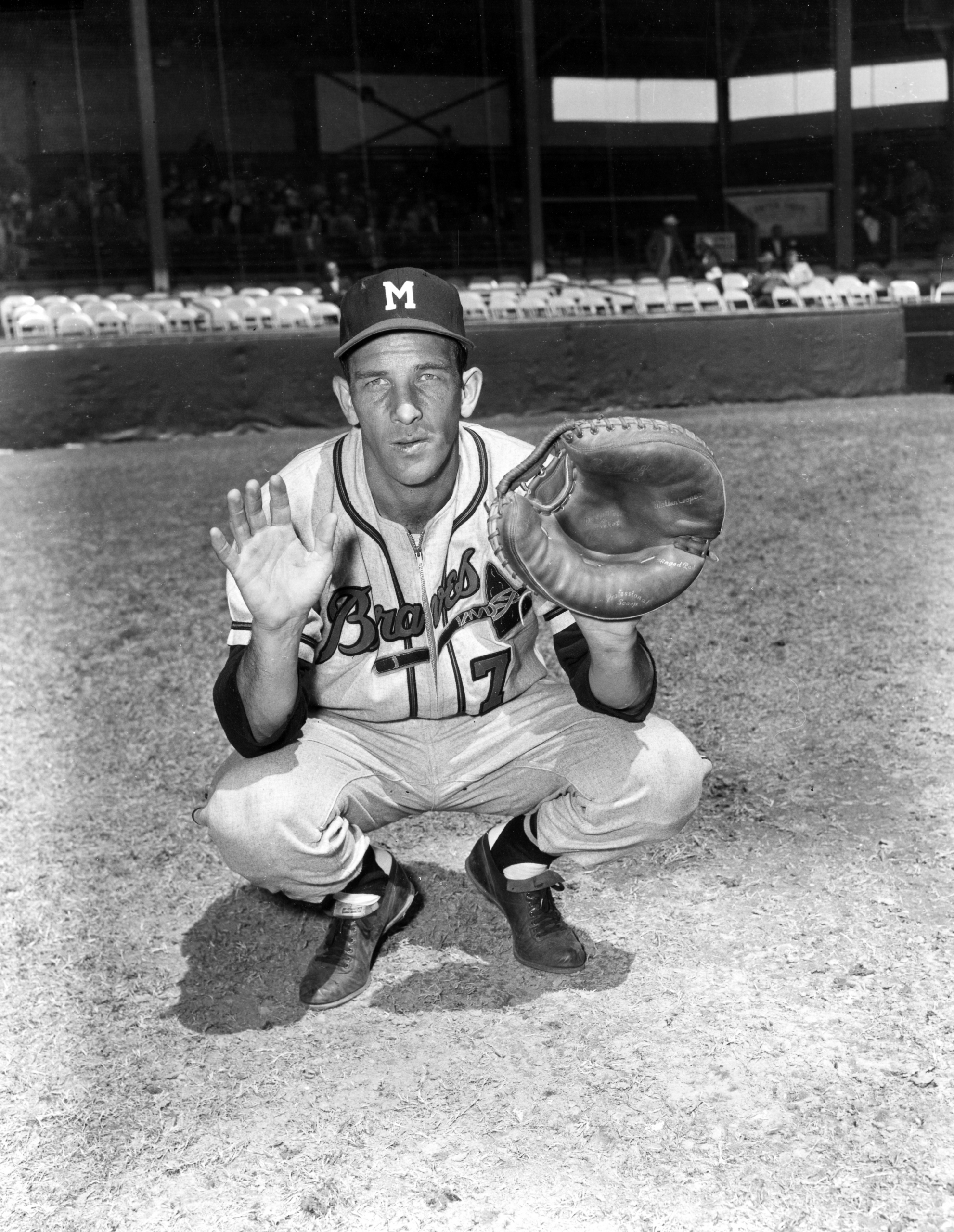

Del Rice

Del Rice was a major-league catcher for 17 years, primarily with the St. Louis Cardinals and Milwaukee Braves. While he was not a good hitter, his longevity was attributable to his excellent defensive skills and his ability to work with pitchers. He also knew how to win as a member of two World Series champions, the 1946 Cardinals and the 1957 Braves.

Del Rice was a major-league catcher for 17 years, primarily with the St. Louis Cardinals and Milwaukee Braves. While he was not a good hitter, his longevity was attributable to his excellent defensive skills and his ability to work with pitchers. He also knew how to win as a member of two World Series champions, the 1946 Cardinals and the 1957 Braves.

Long before there was Neon Deion and even when Bo did not know anything, Del Rice was a two-sport star in basketball and baseball. Delbert W. Rice, Jr. was born on October 27, 1922, in Portsmouth, Ohio, the only child of Del Rice, Sr. and Gladys Rice. Del Sr. worked for the city electric company. Del Jr. was an excellent athlete, playing basketball, football, and baseball in high school, but he was destined to be a catcher from his earliest days: “As far back as I can recall, I was always the catcher on the team,” Rice once said in an interview. “And I always had a good arm.”[1]

That good arm was evident in the neighborhood where Del lived, particularly to one neighbor who happened to be the brother of Branch Rickey, the St. Louis Cardinals’ general manager at the time. Frank Rickey was one of the Cardinals’ top scouts and he did not have to beat too many bushes to find a tall young catcher with professional potential. Rice was 6-feet-2 and weighed 190 pounds. Rickey signed Rice to a contract in 1941, and the 18-year-old embarked on his baseball career with Williamson (West Virginia) of the Class D Mountain State League.

Rice started off with a bang, well, three bangs, actually, as he went 3-for 4 in his first professional game, including a home run. He also picked a runner off first base. First appearances were indeed deceiving, however, as he went on to hit just .248 in 88 games the rest of the season, with only two more home runs.

Despite the poor hitting stats, the Cardinals were impressed enough to bring Rice back to Williamson for 1942. He caught 121 of the team’s 124 games, and the heavy workload seemed to help his hitting as his average improved to .288 with 29 doubles, 3 triples, and 7 home runs. He made the league all-star team.

Rice’s knack for being in the right place at the right time continued after his second season. A shortage of players due to World War II (Rice was classified 4-F because of an old injury) caused many teams to suspend their minor-league operations, resulting in Rice’s promotion at the tender age of 20 in 1943 from Class D all the way to Double-A with (Rochester of the International League. It was clearly too much too soon, as pitchers discovered they could get him out easily with low pitches. A woeful .198 batting average in 66 games was the result, with no home runs, five doubles, three triples, and just 18 runs batted in for the season. On the plus side, he committed only nine errors, after having 20 miscues the year before.

One pitch that did work in Rice’s favor was to Mary Alice Ruel (no relation to Muddy) of Portsmouth, whom he married on January 30, 1943.

With the war still raging in 1944, Rice’s trials from the previous year bore some fruit that season. In 92 games for Rochester, his average climbed to .264, with six homers and a respectable 50 RBIs. He did commit 12 errors, but the increased playing time accounts for the higher total. Overall those numbers were good enough for a one-way ticket to “The Show.”

Before the 1945 season started Rice also had good news from the home front, as his son Ronnie was born in March of that year.

Making the 1945 Cardinals was no easy feat. They had won 105 games in 1944 and then defeated the St. Louis Browns in six games in the World Series. Hall of Famer Stan Musial was in the early stages of his career, and the team boasted such solid players as shortstop Marty Marion and third baseman Whitey Kurowski.

The Cardinals’ catching situation was a bit unsettled as the 1945 campaign approached. Incumbent Walker Cooper and his brother, pitcher Mort Cooper, threatened to boycott St. Louis’s season-opening series against the Chicago Cubs even though they had signed contracts for $12,000.[2] They eventually capitulated, but Walker played only four games before joining the Navy. This gave the starting job to veteran Ken O’Dea, but Cardinals manager Billy Southworth was impressed with rookie backstop Rice. “I know a lot of clubs that would be glad to have Rice for first-string catcher,” Southworth said in a May 1945 interview.[3]

The respect was mutual, as Southworth worked closely with Rice to help him overcome his inability to hit the low pitch. “I didn’t seem to be able to level off properly on a ball down around my knees,” Rice said in a 1945 interview. “But since I’ve been with the Cardinals, Mr. Southworth, who is a fine batting teacher, has taken me in hand, and I think he has ironed out some of the things I did wrong.”[4]

Unbeknownst to Rice, the Cardinals had other irons in the fire between the end of the 1945 season and the start of 1946, which included their intention to trade him to the Dodgers as part of a three-team deal involving Brooklyn, St. Louis, and the Boston Braves. He was supposed to go to the Dodgers and the Cardinals were supposed to receive Mickey Owen, a more experienced catcher, and then send Owen to the Braves in exchange for their primary catcher, Phil Masi. The trade was voided, however, when Owen decided to accept an ill-fated offer to play in the nascent Mexican League.

The trade that did not happen was probably precipitated by the Cardinals selling Walker Cooper to the Giants for $175,000 in January 1946. When Cooper left, he took not only his big bat but a wealth of experience as well. The Cardinals had potential stars in Rice and Joe Garagiola, but they were both inexperienced (Garagiola, in particular was considered a top prospect, even though he was only 20, had only one year of Organized Baseball behind him, and was still in the Army as the season began) and O’Dea was a career backup. “Manager Eddie Dyer’s chief concern was the catching department, (the) only spot where the Cards aren’t at least two deep,” wrote W. Vernon Tietjen in The Sporting News.[5]

After the 1945 baseball season ended, Rice augmented his income by playing basketball with the Rochester Royals of the old National Basketball League. (The NBL would merge with the Basketball Association of America in 1949 to become the NBA. The Rochester franchise is now the Sacramento Kings.) It was the Royals’ first season in the NBL, and they started with a bang. With a roster that included NBA Hall of Famer Red Holzman, NFL Hall of Fame quarterback Otto Graham, and future TV star and baseball player Chuck Connors, the Royals won the league championship in their inaugural season. It was Rice’s only year in professional basketball.

The Cardinals started the 1946 season with O’Dea and Rice behind the plate, neither of whom could be considered an everyday catcher. O’Dea had developed back problems, so owner Sam Breadon traded his starting second baseman, Emil Verban, to the Philadelphia Phillies in exchange for journeyman catcher Clyde Kluttz. Garagiola was added to the mix upon his discharge from the Army in May and started his first game on May 26. Although it probably was not the plan, the Cardinals ended up having catcher by committee, with Garagiola behind the plate in 70 games, Kluttz in 49, Rice in 53, and O’Dea in 22.

The catching conundrum did not seem to bother the Cardinals pitchers. They led the league in earned-run average, complete games, and shutouts. As well, all the talent returning from the military helped the Cardinals win the World Series that year in seven games over the Boston Red Sox after winning the major leagues’ first-ever best-of-three playoff against the Brooklyn Dodgers in two straight games. Garagiola did the bulk of the catching in the fall classic, while Rice appeared in three games and went 3-for-6 with two runs scored.

The Redbirds were winging it again at the catcher’s position in 1947. Kluttz was sold to Pittsburgh, but the Cardinals still retained a trio of catchers with Del Wilber, who had appeared briefly in early 1946, joining Rice and Garagiola on the roster. Although Rice played in more games (97) than either of the others, he was unable to claim the starting job as his own, due partly to a shoulder injury suffered during spring training. He did set a career high for home runs, with 12, but batted only .218 as the Cardinals began three frustrating seasons finishing as the runner-up to the pennant winner.

One season highlight for Rice occurred on August 23 against Philadelphia. In the eighth inning the Phillies had two on, nobody out, and pinch-hitter Charlie Gilbert at the plate. For some reason he tried to bunt with two strikes on him. He made contact, but hit a short foul popup that Rice lunged at and caught with his bare hand. The men on base were running, so Rice gunned the ball to Marty Marion covering second base for the second out; Marion threw it to Musial at first base to complete the triple play. The Cardinals won the game, 5-3.

Rice continued having difficulty claiming the catcher’s job for his own as the 1948 season began. “Asked about his catching problems, Dyer said he was quite satisfied with the receiving of Del Wilber, who has been doing the bulk of the Redbirds’ mask work this spring,” wrote Ray Gillespie in The Sporting News. “Eddie indicated, however, that it would be a dogfight for the job, with Del Rice and Joe Garagiola very much in the running in the event the ex-Air Force captain [Wilber] stubs his toe.”[6]

It must have been quite a stub, because Wilber ended up catching only 26 games that season. In fact, Rice owned the starting job by early May with his solid defensive work. “He caught a whale of a game as we beat the Cubs 3 to 1, May 3,” Dyer said. Del tossed out two base runners and really showed us something when he nailed big Bill Nicholson driving into the plate trying to score.”[7]

Besides his stellar defense, Rice was holding on to the job because he was the best from among a sorry group of hitters. By mid-June, Rice was hitting .196, which was Cobbesque compared with Garagiola’s .088 and Wilber’s .053. These below-average averages prompted the Cardinals to send Garagiola down to their Columbus Triple-A affiliate and bring up 37-year-old Bill Baker, who had not even played in the majors in 1947. Rice still did the lion’s share of the catching for the season, appearing in 100 games and hitting a career-low .197 for the year (a mark he equaled in 1955 with the Braves), with only four home runs and 34 RBIs. Of the 100 games he played in, he caught in 99, which under the rules at the time meant that he missed out on qualifying for the league fielding percentage title for his position by one game. He would have won it, too, as he had a league-high .996 fielding percentage, but Masi of the Braves won it with.988.

Rice caught a break during spring training 1949. Unfortunately, the break was in his right thumb, but that did not prevent him from starting on Opening Day in Cincinnati. Garagiola was back up with the big club by then, and Dyer platooned them for the season, with Garagiola playing against right-handers and Rice against southpaws. Rice batted .236 in 92 games and equaled his total for home runs from the previous season with four; but his RBI total dropped to 29.

The catcher’s job became Rice’s by default early in 1950. Actually, “de” fault was Garagiola’s. He began the season as the number one backstop, but on June 1 he separated his shoulder tripping over Jackie Robinson’s leg at first base. In 130 games, Rice’s average improved to .244 and his production numbers were better as well, with nine homers and 54 RBIs.

Rice’s numbers were similar in 1951 (.251, 9 HRs, 47 RBIs), but he made a significant change in his hitting style that improved his confidence going into the 1952 season. He finally heeded the advice of coaches and managers and stopped trying to pull everything to left. His epiphany came in a late-season game against the Giants. “There were runners on first and third, one out, and the count ran to three balls and two strikes,” he said. “I made up my mind I was going to right field or else. I guess I fouled off four or five pitches, but finally I shot one to right, for I knew I could do it.”[8]

The 1951 season was also significant for Rice because Garagiola, his rival for the catching job, was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates in June, ensuring that Rice would get most of the work behind the plate.

That is exactly what happened in 1952. Rice played in 147 games that year (in a 154-game schedule), hit double digits in home runs (11) for the second and last time, and set a career high for RBIs with 65. The workload did not affect his defense, either. He made only six errors in 764 chances for a .992 fielding percentage, second in the league to Roy Campanella’s .994.

Rice’s fine play in 1952 was a prelude to an All-Star season in 1953. His offensive numbers were not as good, but he remained steady defensively, not committing his first error of the season until his 64th game. Campanella won the fan poll for starting catcher in the All-Star Game in Cincinnati that year, but NL manager Charley Dressen chose Del Crandall and Rice, who came in second and third respectively in the balloting, as backups. Rice injured his finger on a foul tip six days before the game, causing him to miss his only chance of making an All-Star appearance.

Injuries and the cumulative effects of a heavy workload took their toll on Rice in 1954. In a June 7 collision at the plate, Campanella, the baserunner, caught Rice in the calf with his spikes, putting him out for a week. Rice’s playing time also diminished because his replacement, Bill Sarni, batted .300, hit nine home runs, and had 70 RBIs. As a result, Rice played in only 56 games; his days as a full-time catcher were over.

Not surprisingly, Rice was traded to the Milwaukee Braves on June 3, 1955. His stock had fallen to the point where the Cardinals received Pete Whisenant, who was playing at Triple-A Toledo, With perennial All-Star catcher Crandall on the Braves roster, Rice was clearly going to play a backup role.

Although he was guaranteed diminished playing time in Milwaukee, Rice could get comfort from the fact that he was joining a powerful team that was in the middle of a love affair with the city since moving to Wisconsin from Boston. With a power supply led by Hank Aaron and Eddie Mathews, and with Warren Spahn and Lew Burdette on the mound, the Braves finished second to the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1955 and 1956.

Despite being a backup, Rice certainly contributed to the Braves’ 1957 championship. Milwaukee was in the middle of a September swoon, having lost eight games out of 11, caused by, of all things, a hitting slump. Their lead in the NL had dwindled from 8½ to 2½ games, but on September 16 Rice led a 14-hit attack by driving in two runs with a single and home run against the Phillies in a 5-1 win that got the team out of its doldrums. “If Rice didn’t get another hit all season, and if his tenure as first-string catcher lasted no more than a game or two, he had done something not even the best hitters on the club could do,” wrote Bob Wolf in The Sporting News. “He had shown the way out of a batting slump that had threatened to cause the complete collapse of the club.”[9]

Rice started that night thanks to pitcher Bob Buhl, for whom Rice was his personal catcher. The pairing worked, as the battery kept going and going until Buhl put together an 18-8 record and led the league with a .720 winning percentage. The World Series was another story, as Buhl had a 0-1 record in two starts with a 10.80 ERA and a total of only 3? innings pitched. Rice started behind the plate in Games Three and Six and had one hit in seven appearances. The Braves’ triumph in seven games over the New York Yankees gave Rice his second World Series ring. The Braves lost a seven-game rematch to the Yankees in 1958, but Rice did not play in that Series.

Rice played for the Braves until he was released after the 1959 season. He signed in October with the Chicago Cubs as a free agent and caught Don Cardwell’s no-hitter against the Cardinals on May 15, 1960. He also played for the Cardinals and Orioles that season, and when the American League expanded to ten teams, he became the very first Los Angeles Angel, signing on as a player-coach for the Angels’ inaugural season in 1961, Rice’s last as a player. On the personal front, Rice also got married for a second time before that season started; his first wife, Mary Alice, had died of leukemia in November 1956. Del married Pat Niebur in February 1961, and the couple had a daughter, Julie Ann, in 1962.

After retiring as a player Rice coached for the Angels and the Cleveland Indians, then began paying his dues as a minor-league manager, starting at San Jose of the Class A California League in 1968. In 1969 he moved up to the El Paso Sun Kings of the Double-A Texas League, where he made a splash right away by being ejected in his first game. Despite that inauspicious start, he managed in El Paso for two years, then took over the Triple-A Salt Lake City Angels (Pacific Coast League) in 1971. Rice skippered this squad to first place in the Southern Division, then defeated Tacoma in the league playoffs, and was named The Sporting News Minor League Manager of the Year. For that he was rewarded with the manager’s job with the Angels.

Whether it was a reward or a punishment in disguise is an interesting question, because the Angels were a team in turmoil: “There wasn’t any fun for the Angels in 1971,” wrote Dick Miller in The Sporting News. In 1971 Rice’s predecessor, Lefty Phillips, wasn’t a Captain Bligh, but tensions surrounded the California clubhouse. Tony Conigliaro couldn’t bear the stress and quit the game. Alex Johnson was suspended. Chico Ruiz was charged with pulling a gun on a teammate.[10]

It would probably have taken a miracle to turn the 1972 California Angels around quickly, especially when they lost six out of their first eight games. The team ended up with a 75-80 record in a strike-shortened season, and even though the team had a higher winning percentage than the previous season, Rice was given a ticket on the Angels’ managerial merry-go-round, becoming the third manager in five years to be fired by the club. He stayed on as a scout, but quit the Angels organization in 1978 when owner Gene Autry asked him to take a $6,000 pay cut.

Rice continued in baseball as a scout with the New York Yankees and San Francisco Giants. He battled cancer for several years and died on January 26, 1983, while waiting to be introduced at a benefit dinner in his honor in Buena Park, California. He was 60 years old.

This biography is included in the book “Thar’s Joy in Braveland! The 1957 Milwaukee Braves” (SABR, 2014), edited by Gregory H. Wolf. To download the free e-book or purchase the paperback edition, click here.

Sources

http://baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Del_Rice.

Graham, Frank, Jr., “The Great Mexican War of 1946,” Sports Illustrated, September 19, 1966.

baseball-reference.com/players/c/coopewa01.shtml.baseball-reference.com/managers/southbi01.shtml.Daly,

Jon Daly, biography of Billy Southworth.

baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Joe_Garagiola.

baseball-reference.com/players/m/masiph01.shtml.

baseball-reference.com/players/o/o’deake01.shtml

Paper of Record

sportsecyclopedia.com/nba/rochester/rochroyals.html

basketball.wikia.com/wiki/National_Basketball_League

baseball-reference.com/minors/league.cgi?code=PCLclass=AAA

Notes

[1] Frederick G. Lieb, “Scout Next Door ‘Discovered’ Del Rice, Card Catching Rookie,” The Sporting News, July 5, 1945.

[2] Frederick G. Lieb, “Coopers, Brother Battery, Call Own Strike, Then Call It Off in Pay Row,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1945.

[3] Frederick G. Lieb, “Cards Start to Hit Fence as Ace Hurlers Hit Stride,” The Sporting News, May 10, 1945.

[4] Ibid.

[5] W. Vernon Tietjen, “Cardinals Well-Padded in All Except Pad Corps,” The Sporting News, April 4, 1946.

[6] Ray Gillespie, “Dyer Chuckles Over Redbird Chucking and Nippy’s Nifty Work at First Base,” The Sporting News, April 28, 1948.

[7] Ray Gillespie, “Birds, Browns, Show More Power at Gate,” The Sporting News, May 12, 1948.

[8] Bob Broeg, “Younger Redbirds to Get Full Chance to Make Grade – Saigh,” The Sporting News, November 28, 1951.

[9] Bob Wolf, “Buhl-and-Rice Battery Flicks Beacon for Fog-Bound Braves,” The Sporting News, September 25, 1957.

[10] Dick Miller, “ ‘We’ll Have Fun,’ Says New Angel Pilot Rice,” The Sporting News, December 25, 1971.

Full Name

Delbert W. Rice

Born

October 27, 1922 at Portsmouth, OH (USA)

Died

January 26, 1983 at Buena Park, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.