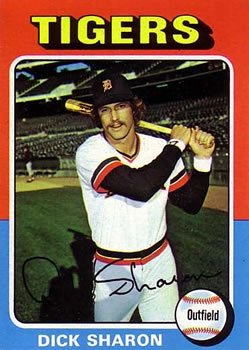

Dick Sharon

At the start of spring training in 1974, longtime Detroit sportswriter Joe Falls had a problem. He could not decide which Tiger player was his favorite. He called it a “tossup” between veteran Ike Brown and second-year outfielder Dick Sharon. Falls wrote presciently that Brown, who would play the final two games of his major-league career in 1974, knew his time in the majors wouldn’t “last very much longer.” Regarding Sharon, Falls wrote, “he’s a fun guy and it’s interesting to talk to him about other things than baseball. Except for Dick McAuliffe, he’s the only athlete I’ve ever known who asks me about ‘my’ job.”1

At the start of spring training in 1974, longtime Detroit sportswriter Joe Falls had a problem. He could not decide which Tiger player was his favorite. He called it a “tossup” between veteran Ike Brown and second-year outfielder Dick Sharon. Falls wrote presciently that Brown, who would play the final two games of his major-league career in 1974, knew his time in the majors wouldn’t “last very much longer.” Regarding Sharon, Falls wrote, “he’s a fun guy and it’s interesting to talk to him about other things than baseball. Except for Dick McAuliffe, he’s the only athlete I’ve ever known who asks me about ‘my’ job.”1

Falls described Sharon well. A superb, multi-sport athlete at Sequoia High School in Redwood City, California, he played baseball well enough to be the Pittsburgh Pirates’ number one pick—number nine overall—in the 1968 amateur draft. The 6-foot-2, 195-pound righty hitter and thrower played nine seasons in professional baseball. Three of those were in the major leagues, two with Detroit and one with the San Diego Padres. Chronic back problems prematurely ended his baseball career in 1976.

Between then and now he has demonstrated the breadth of interests noted by Falls. An avid golfer and outdoorsman, Sharon moved to northern Idaho, then to western Montana, and finally to Indiana. While doing a variety of jobs for the past 45-plus years, he always found time for his first sporting love—fishing. He worked for years as a professional fishing guide, taking clients on tours in the United States and Central and South America. Today, he occupies his time writing what should eventually be a memoir, golfing, cooking, enjoying the outdoors with his oldest daughter, and doing the New York Times Sunday crosswords—an interesting guy, to be sure.

Born in San Mateo, California, on April 15, 1950, Richard Louis Sharon was the second child of Benjamin Malcolm and Edith Muriel Sharon (née Brownlie), following an older brother named Michael. Benjamin worked in the wholesale grocery business as a general manager and buyer, Edith as a homemaker. Sharon described his childhood fondly. His father taught him to fish and played baseball, basketball, and football with his sons. His mother, an excellent homemaker, shouldered the burden of her husband’s illness and subsequent death in 1964, skillfully maintaining the family’s standard of living.

Early on, Sharon exhibited obvious athletic talent. From the age of nine he played baseball with much older kids. He recalled, “I knew if I could play with kids three or four years older and still be a standout, I was pretty good.”2 At 11, he made his Little League’s All-Star team.3 He repeated that honor-star in 1962.4

His high school years at Sequoia brought more athletic success and recognition: As a freshman, Sharon starred in football,5 basketball,6 and baseball, leading the South Peninsula Athletic League (SPAL) in batting average, and winning first-team all-SPAL honors.7 However, his next three high school years proved trying. In September 1965, the discovery of a cyst on his vertebrae and subsequent surgery ended his football playing days.8 The treatment did not resolve his nagging back problems; in 1966, he played only 10 games for the Sequoia varsity baseball team but still made the all-SPAL second team.9

At the beginning of 1967, his participation in a semipro baseball game resulted in the SPAL suspending him for almost the entire 1966-67 high school basketball season. Sharon ran afoul of an SPAL rule that prohibited players playing “any outside sport while he is competing for a league school.”10 Getting back on the diamond after the disappointment of being unable to play basketball, Sharon’s 1967 baseball season resulted in another first team all-SPAL selection.11

During the summer of 1967, chronic back problems prevented Sharon from playing American Legion baseball until August. Then, two weeks after his return, he suffered a compound fracture of his right ankle while crashing into the fence after a fly ball.12 The horrific injury put his athletic future in doubt,13 but he worked tirelessly to recover, returning to the basketball court by mid-January.14 Sharon then produced another fine season for the Sequoia baseball team, earning another first-team all-SPAL selection and finishing with SPAL career records for total bases and RBIs.15

Sharon had been heavily scouted during high school, and on June 6, 1968, the Pittsburgh Pirates drafted him in the first round of the amateur draft, the number nine selection overall.

Sharon began his professional career with the Pirates’ team at Bradenton, Florida, in the Gulf Coast (Rookie) League. Though he hit only .166 in 53 games, the season featured at least one milestone: On July 28, he hit his first professional home run, a two-run blast off Don Brown, a right-hander in the Twins system.16 Looking back on the rookie experience he said, “It’s really hard to make it in professional baseball. If there are 40 guys in a rookie camp, they’re all used to being the best player on their team, everywhere they’ve played. But 20 will get cut after two days, maybe 12 will get as far as Single-A, maybe six to Double-A, maybe 2 to Triple-A. Maybe one of the 40 will be good enough to get to the majors.” Of course, he was that one.

In 1969, Sharon played at Gastonia, North Carolina, in the Class-A Western Carolina League. He began the season struggling but played much better after late May. For the year, he hit .216, with three home runs and 47 RBIs. While not hitting as well as he undoubtedly hoped to, Sharon’s defense produced rave reviews. One Gastonia sportswriter observed that while “the fleet center fielder started slowly with the bat here . . . He already wears a ‘big league glove.’”17

His 1970 season Salem in the Carolina League (also Class A) showed dramatic offensive improvement. While hitting a modest .254, he demonstrated excellent power and run producing ability. He finished fourth in the league with 78 runs, tied for third with 22 home runs, third in RBIs with 71, sixth with a .457 slugging average, and eighth with a .793 OPS.

That season earned him a promotion to Pittsburgh’s Double-A Eastern League club, the Waterbury (Connecticut) Pirates. His main offensive statistics for Waterbury were down from his 1970 numbers at .255 with seven home runs and 46 RBIs, yet he still finished tied for 10th in the league in runs scored, tied for 13th in RBIs, and third with 26 stolen bases.

Sharon played winter ball for the Mayos de Navojoa in the Mexican Pacific League. He quickly discovered that fans often threw things at outfielders, with “cups of urine, spark plugs, and bolts” being particular favorites. Unfortunately, Sharon also had a couple of grim experiences that were far more serious than having to dodge missiles from the bleachers. In early November, the team traveled by bus for a three-game road series. Bus travel on road trips could be an ordeal—the buses were often old and always uncomfortable, and the traffic on the roads was frequently unsafe and chaotic. On this trip, the bus slammed into a truck that had stopped in the middle of the road. The impact crushed the front of the bus, leaving Francisco Campos— a fine player who had won the batting title of the Triple-A Mexican League in 1970—trapped from the waist down in the mangled wreckage. Eventually, doctors had to amputate his right leg. Sharon escaped with comparatively minor injuries—a dislocated shoulder put back into place by a teammate, and a bloody gash on the “left side of my head.”18 Miraculously, the accident resulted in no fatalities.

In late December, Zelman Jack, one of Sharon’s teammates at Waterbury, was not so lucky.

On December 23, Jack, who played for the Guasave Cotton Growers, reportedly died while trying to get into a closed nightclub. The police reported that he “fell through the roof . . . when he went there early Thursday morning and found it closed.”19 Later accounts reported that Jack “tried to jump over a wall surrounding the night club, fell and fractured his skull.”20 Sharon, who was with Jack shortly before he died, believes Jack was murdered. The night before Jack’s death, Sharon’s Navojoa club had played in Guasave. After the game, Jack had joined several other players at a local cantina for “a few beers.” A number of men and women noticed the ballplayers and came over to join them. Jack eventually left in a cab with one of the women, returning around an hour later. At that point, “Z got out of the car . . . said something to the driver and got back in the vehicle.”21 That was the last time he saw Jack alive.

The next night, Jack did not appear at the park for the scheduled game. Although several players asked the Navojoa manager to contact the police, they did not arrive until the next day. One of the police told one of the Mexican players on the team that they had found Jack’s body. The police asked Sharon and some of the other players to go to the morgue and identify the body. The coroner spoke English and told them that Jack had been found in an alley in a neighborhood with a “long history of violence, drugs, prostitution and turf wars.” The police apparently knew both the woman and the man responsible for Jack’s death—but both were now “gone.” When Sharon saw the injuries on Jack’s corpse, he knew that his friend had been beaten, robbed, and murdered—and that there would be no legitimate investigation. Unsurprisingly, the life-changing experiences he had in Mexico have remained vivid memories. 22

After his Mexican ordeals, Sharon played in 1972 for Charleston, West Virginia, in the Triple-A International League. There, he had another decent season at .268 with 14 home runs and 49 RBIs, finishing 14th in the league in runs scored, tied for sixth in stolen bases, and tied for ninth in home runs. At the end of that season, Sharon had a secret. More than three years before the Seitz decision nullified the reserve clause,23 he could become a free agent for the 1973 season. In early 1972, after the 1971 Mexican winter league season ended, Sharon returned to Redwood City and tried “two or three times to deposit” his final check from the Waterbury club.24 Each time it bounced. Consultation with his brother Michael, a law school student, revealed that the Waterbury contract required that he be paid within 30 days of the season’s end. A violation of that provision nullified the contract, resulting in free agency for the player.

Armed with that knowledge, Sharon then spoke with Pirates GM Joe Brown. When he explained the situation, Brown replied “You can’t do that.” After checking the contract, Brown called the next day, asking Sharon, “What do you want to do?” Sharon said that he “wanted to be a free agent.” Brown then offered to “double my salary if I played for Charleston in 1972.” Sharon accepted the offer but advised Brown that at the end of the season he expected to either “become a free agent or be traded.”25

In compliance with Sharon’s demand, on November 30, 1972, the Pirates traded him to the Detroit Tigers for two pitchers: minor-league left-hander Jim Foor and minor-league right-hander Norm McRae.

His spring performance drew praise from Tigers manager Billy Martin, who declared, “Dick Sharon has changed some things around here. . . [he’s] responsible for making our veteran outfielders push themselves harder.”26 After what he described as a “great spring,” Martin told Sharon two days before the season started that he’d made the opening day roster. However, as he prepared to leave for Detroit, Tigers coach Dick Tracewski informed him that because of some “roster problems” he would be sent to Toledo.

While Sharon toiled in Toledo, the Tigers—1972 American League Eastern Division champs and the oldest club in the majors—stumbled along through May 10, playing sub-.500 baseball (13-15). On May 11 the club placed outfielder Willie Horton on the 15-day disabled list with a wrist sprain. They recalled Sharon from Toledo the next day.

He debuted on Sunday, May 13, playing two innings as a defensive replacement in right field against Milwaukee at Tiger Stadium. The following day he was in the starting lineup at Yankee Stadium against Yankee left-hander Fritz Peterson. In his first major-league at-bat, in the top of the second, he got credit for an RBI when he reached first on a bases-loaded error by Yankee shortstop Gene Michael. Later in the inning, Matty Alou threw him out at third when he tried to advance on a fly ball. In Detroit’s eighth inning, he drove home his second run of the game with a double. He finished the contest, an 8-0 Tigers win,27 1-4 with two RBIs.

Detroit sportswriter Jim Hawkins raved about Sharon’s performance. After talking about another player’s successful night, he said, “But that was nothing compared to the night Dick Sharon enjoyed. The 23-year-old outfielder, just 72 hours removed from Toledo, made his first major league start, connected for his first major league hit and drove in his first two major league runs.”28

Sharon played sporadically during the 1973 season. In 91 games, he made only 43 starts, and in 14 of those he left the game for a pinch-hitter. His season highlights included a 13th-inning single to drive in the winning run in a 1-0 win over the World Series champion Athletics and Rollie Fingers. His first major-league homer came off Chicago right-hander Eddie Fisher, a solo drive in a 10-2 loss at Comiskey Park. His best day in the majors occurred on July 10, a 4-for-4 performance with two home runs—the second against Texas Ranger left-hander Jim Merritt—was the winning run in a 5-4 Tiger victory.

Another memorable moment for Sharon came against the Angels—Nolan Ryan’s no-hitter in Detroit on July 15, 1973. Shortly before game time, Willie Horton came down with a “24-hour virus” that afflicted many right-handed batters when they were scheduled to face Ryan. Sharon found himself in the starting lineup, playing right and hitting sixth. Obviously, Ryan had overpowering stuff that day. As four of the first five Detroit hitters struck out, someone said “good luck, Rook.” Jim Northrup, the only Tiger to put the ball in play in the first two innings told Dick, “Strap it up Nutsy! He’s got it today!” In fact, Ryan methodically dispensed of the Tigers each inning, finishing the game with 17 strikeouts—a major-league record in a no-hitter (tied in 2015 by Washington’s Max Scherzer). Sharon remembered, “Ryan’s domination that day was so complete, so majestic, that collectively we were almost proud to be part of a game that was certainly one of the most spectacular displays of greatness in baseball history.”29

Following Ryan’s gem, the team remained competitive until mid-August, when 10 losses in 15 games dropped them to 7½ games back on August 30. Four days later, the Tigers dismissed Martin, replacing him with coach Joe Schultz.30 The club eventually finished 85-77, in third place in the division, 12 games behind the champion Baltimore Orioles. Sharon ended the year at .242 with seven home runs and 16 RBIs. He slugged a respectable .410 with 16 extra base hits (nine doubles) among his 43 hits.

Named Detroit’s “Rookie of the Year” after the season, he expected to have a bigger role for the team in 1974. Indeed, that December, GM Jim Campbell called him “a pretty good player. In fact, he’s one of the most sought-after young players we have in our organization.”31

However, things did not work out that way—1974 proved to be a disastrous year for the team and a disappointing season for Sharon. The club, once again the oldest in baseball, played reasonably well in the first half. After the games of July 5, the Tigers were 43-37, in third place in the division, only one game out of first. Then the bottom dropped out: a 3-2 loss to Chicago on July 15 dropped them below .500 for good. On August 18, a 13-3 drubbing at the hands of the Oakland Athletics put them in the AL East cellar. They would remain there the remainder of the season.

Sharon hardly played as the 1974 season opened. In the off-season, the Tigers hired former Yankee manager Ralph Houk to run the club. “He didn’t even know who I was,” remembered Sharon.32 Indeed, during the first 15 days of the season, Sharon had only one at-bat, being used only twice as a defensive replacement. On April 20, Houk gave Sharon his first start against Milwaukee left-hander Clyde Wright. For the next few weeks, Sharon continued to play only occasionally. By May 30, he had appeared in only 18 of the Tigers’ 45 games. In only 53 at-bats, he was hitting .264, better than outfield mates Mickey Stanley and Northrup. In the next three weeks, he got only 14 at-bats. Not surprisingly, his batting average dropped.

As the team struggled, Houk continued to ignore him—the five games of August 17-21 were the most he played consecutively the entire season. As the Tigers dropped into last place, Sharon played only once after August 31. Given his limited playing time, his season totals—a .217 average, two home runs, and 10 RBIs—again were hardly surprising.

Predictably, on November 18, 1974, Detroit sent him—along with shortstop Ed Brinkman and minor-league right-hander Bob Strampe—to the San Diego Padres for slugging first-baseman Nate Colbert. Sharon learned of the trade while playing winter ball in Puerto Rico. There, he played for league champion Bayamón and found the quality of baseball excellent, Triple-A level at a minimum. He loved playing in Puerto Rico and found it “great being in a different community of baseball players.”33

Sadly, the San Diego experience proved far less satisfying. Two months into the season, he had only 27 at-bats and was hitting .111. He played more after that, hitting .217 over the last four months to raise his final average to .194. During the season, he played in 91 games, starting only 35. He was also used as a pinch-hitter 38 times. Sharon finished the season with seven doubles, four home runs, and a career-high 20 RBIs. Highlights were few, but he did hit a three-run home run in a 7-6 loss at San Diego against Reds’ right-hander Jack Billingham on July 4. On September 7, Sharon hit his final major-league homer, a solo clout against Houston left-hander Dave Roberts at the Astrodome.

Still only 25, Sharon concluded his major-league career against the Giants in San Francisco, going 0-for-2 with an RBI. Overall, his major league career statistics showed a .218 lifetime average, with 20 doubles, 13 home runs, and 46 RBIs. Despite his modest average, he showed above-average power, as 32.5 percent of his 102 hits went for extra bases.

After the season, Sharon was traded three times in five months.

- In October, San Diego dealt him to St. Louis for outfielder Willie Davis. The Cardinals assigned Sharon to Triple-A Tulsa.

- On January 12, 1976, the St. Louis organization traded him to California for minor-league pitcher William Rothan. The Angels assigned him to Triple-A Salt Lake City.

- Finally, on March 3, 1976, the Angels traded him, along with John Balaz and Dave Machemer, to Boston for Dick Drago.

The Red Sox assigned Sharon to Triple-A Pawtucket, Rhode Island.34 With his back hurting and believing he could no longer physically perform in the big leagues, Sharon finished his professional career with the PawSox. Playing in only 77 of his club’s 138 games, he hit .232 with 8 home runs and 38 RBIs.

Though it wasn’t a year to remember, Sharon reminisced about one unforgettable event that occurred during the season. Playing center, he made three “remarkable” catches in two innings. After his third sparkling play, Rhode Island (Pawtucket) manager Joe Morgan—one of Sharon’s “favorite skippers”—came out of the dugout, “walked to center, shook my hand, then went back to the dugout. I never saw or heard of any other manager doing that.”35

In May 1977, Sharon moved to northern Idaho and began doing home remodeling. Other jobs there included a short time selling accident and health insurance door-to-door, and several years managing property. Most important, he found time to play golf, do a little hunting, and do as much fishing as he could.

In 1984, he relocated to Montana, becoming part-owner of a Ford dealership. Soon, Sharon found a calling as a professional fishing guide, owning a home and a fly-fishing shop on the Beaverhead River, one of Montana’s most famous trout-fishing rivers. 36 The same drive that had made him a major-league player made him an expert fly fisherman. As a guide, he loved “making people happy,” and meeting people from all over the world provided a constant stream of new experiences and friendships.37 For example, after guiding Starsky and Hutch television star Paul Michael Glaser on one fishing trip, the actor told him that if Sharon was ever in Los Angeles to call him and they would play golf at the very exclusive Riviera Country Club. Sometime later, Sharon had a West Coast fishing trip scheduled that originated in Los Angeles. He called Glaser and they played Riviera in a foursome that included actor Gabe Kaplan of Welcome Back Kotter and a Hollywood producer whose name Sharon did not remember.

By 2015, Sharon had guided fishermen on both fresh and saltwater trips to Alaska and Montana in the United States; to Costa Rica, Panama, and Belize in Central America; to Argentina and Chile in South America; and to Cuba. In addition, during the era of glasnost and perestroika in Russia, Sharon and five other expert fly fishermen “fished rivers that had never been fished” in that turbulent country38.

In late 2019, Sharon moved to Indiana. There, he is closer to family, but “living in a place without mountains” makes him miss the majesty of the Northern Rockies. Sharon, who is presently single, has two daughters who are the joys of his life. Katherine (“Kate”), 36, holds a PhD in Nutritional Immunology from Texas Tech University and currently works as a Senior Research Scientist in the animal pharmaceutical field. In 2011, Kate won a national title in an individual rodeo event and was a big reason Montana State women won that year’s National Intercollegiate Rodeo Association Championship.39 Hannah, 34, was described by her father as “one of the most respected horse trainers in Montana and a great rodeo performer in barrel racing and team roping.”40

Sharon is justifiably proud of his baseball career—he was a tremendous and intense player. Even as a child, he played hard and sometimes recklessly, crashing into walls, diving for balls, and generally risking his body for his team. He has had (or will have had) more than two dozen surgeries: on his back, the ankle he broke in 1965, and on both his wrists. He has also had a knee replaced and suffered a torn Achilles tendon and torn hamstrings. His physical maladies forced him to quit professional baseball, leave his guide business, and more recently, to give up his beloved sport of fly fishing.

Perhaps equally important, he is one of about 500-600 living former major-league players who retired before 1980, and who have been left out of the sport’s excellent pension plan. Rather than receiving a lifetime pension, players from that era who did not accrue four years of service credits (a total of at least 688 days on a major-league roster or disabled list) receive “non-qualified retirement payments,” with the maximum being around $11,500 annually. When these players die, their benefits cease. There are no survivor benefits with this plan. Many of these “non-vested retirees” have had to file “for bankruptcy at advanced ages,” lost their homes through foreclosure, and/or “are so sickly and poor that they cannot afford adequate health care coverage,” according to an article in the Billings Gazette.41 Today, the average franchise value is greater than $2.4 billion, the average player salary is a shade under $5 million,42 and the Major League Players Association’s Welfare Fund is worth at least an estimated $3.5 billion.43 In such a business, surely there must be enough money to ease the plight of these former players. Like Sharon, these men loved the game, but they have been forgotten.

As he did through the injuries and disappointments in his baseball career, in 2024, Sharon continues to persevere. The life he built after baseball has been and continues to be rich—filled with family, and a variety of outdoor, athletic, and cerebral activities and interests. Joe Falls would not have been surprised.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dick Sharon for sharing his memories.

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and David Bilmes and fact-checked by Dan Schoenholz.

Sources

Belleville News-Democrat

Billings Gazette

Bradenton Herald

Detroit Free Press

Gastonia Gazette

College National Finals Rodeo: https://collegerodeo.com/cnfr/

Peninsula Times Tribune

Redwood City Tribune

The Sporting News

https://www.statista.com/

Notes

1 Joe Falls, “Houk Hard Put to Match Billy?” Detroit Free Press, March 17, 1974, 67. Information on the 1968 Amateur Draft comes from https://www.baseball-reference.com/. All game or statistical information comes from either Baseball-Reference, or https://www.retrosheet.org/

2 Dick Sharon, telephone interview with Robert Bionaz, on August 6, 15, 22, and 23, 2024 2024 (hereafter Sharon-Bionaz interview).

3 “Eight Local All-Star Teams in Area,” Redwood City Tribune, July 11, 1961: 9.

4 “Redwood City Little League All-Stars,” Redwood City Tribune, July 18, 1962: 9.

5 “Sequoia Tailback Lost for Season,” Redwood City Tribune, September 13, 1965: 10.

6 “Tim Fondiller Top SPAL B Cager,” Redwood City Tribune, March 16, 1965: 13.

7 Bruce Meadows, “Scots’ Pignataro is Player of Year,” Redwood City Tribune, June 3, 1965: 15.

8 “Sequoia Tailback Lost for Season,” Redwood City Tribune, September 13, 1965: 10.

9 Dick O’Connor, “San Carlos tops dream team,” Peninsula Times Tribune (Palo Alto), May 31, 1966: 17.

10 Bill Shillstone, “Baseball vs. Basketball”, Redwood City Tribune, January 12, 1967: 16.

11“1967 All-SPAL Baseball Team,” Redwood City Tribune, May 26, 1967: 14.

12 “RC Legioners Lose; Dick Sharon Injured,” Redwood City Tribune, August 16, 1967: 14.

13 Paul Savoia, “Sequoia’s Hard-Luck Case,” Redwood City Tribune, August 25, 1967: 14.

14 Bruce Meadows, “Vikings upset by ‘Cats,” Peninsula Times Tribune, January 17, 1968: 53.

15 “14 SPAL baseball marks take beating,” Peninsula Times Tribune, August 3, 1968: 17.

16 Kent Chetlain, “SHARON HOMERS, DOUBLES: Sells Hurls Bucs to 10-2 Victory,” Bradenton Herald, July 29, 1968: 11.

17 Neale Patrick, “Two Top Draft Choices Play With G-Pirates,” Gastonia Gazette, June 24, 1969: 5.

18 Tomas Morales, “Highway Crash Ends Career of Mexican Player,” The Sporting News, November 20, 1971: 55. There is no available statistical information for the 1971-72 Mexican Pacific League. Sharon-Bionaz interview.

19 “Former G-Pirate Zelman Jack Dies,” Gastonia Gazette, December 25, 1971: 5.

20 Art Vollinger, “An ART for Sports,” Belleville News-Democrat, (Belleville, Illinois), January 11, 1972: 11.

21 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

22 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

23 Dick Young, “Baseball’s Reserve Clause is Dead . . . Maybe,” Daily News (New York), December 24, 1975: 37.

24 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

25 Watson Spoelstra, “Rookie Sharon Builds Fire Under Tiger Vets,” The Sporting News, March 31, 1973: 35. Sharon-Bionaz interview.

26 Watson Spoelstra, “Rookie Sharon Builds Fire”.

27 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

28 Jim Hawkins, “Tigers Get Moving with Coleman, 8-0,” Detroit Free Press, May 15, 1973: 1-D, 2-D.

29 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

30 Jim Hawkins, ‘My Record Speaks for Itself – – Billy,” Detroit Free Press, September 4, 1973: 37.

31 Jim Hawkins, “Campbell Answers Critics of Tigers’ Mini-Deals,” The Sporting News, December 29, 1973, 32.

32 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

33 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

34 The franchise was known as the Pawtucket Red Sox for every other season it was the Triple-A affiliate of the Boston Red Sox affiliate (1973-2020).

35 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

36 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

37 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

38 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

39College National Finals Rodeo: https://collegerodeo.com/cnfr/, Accessed August 29, 2024.

40 Sharon-Bionaz interview.

41 Douglas Gladstone, “Six hundred forty men iced out by MLB,” Billings Gazette, February 8, 2019: A6.

42 Christina Gough, “Major League Baseball average player salary,” June 13, 2024. https://www.statista.com/statistics/236213/mean-salaray-of-players-in-majpr-league-baseball/, Accessed August 27, 2024.

43 Douglas Gladstone, “Six hundred forty men iced out by MLB,” Billings Gazette, February 8, 2019: A6.

Full Name

Richard Louis Sharon

Born

April 15, 1950 at San Mateo, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.