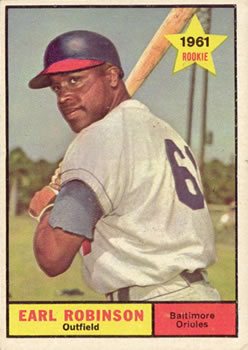

Earl Robinson

Earl Robinson was a two-sport star at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1950s, leading the Golden Bears to the College World Series and finishing his basketball career among the school’s all-time leading scorers. After becoming the first African American to receive a bonus contract, he spent parts of four seasons between 1958 and 1964 as a part-time outfielder with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Baltimore Orioles.

Earl Robinson was a two-sport star at the University of California, Berkeley in the 1950s, leading the Golden Bears to the College World Series and finishing his basketball career among the school’s all-time leading scorers. After becoming the first African American to receive a bonus contract, he spent parts of four seasons between 1958 and 1964 as a part-time outfielder with the Los Angeles Dodgers and Baltimore Orioles.

Robinson’s athletic accomplishments were only part of his story. He earned a doctorate in education and spent decades as a speech and communications professor. When one of baseball’s all-time greats – Rickey Henderson – was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, it was Robinson who helped him craft his induction speech.

Earl John Robinson was born on November 3, 1936, in New Orleans, Louisiana. According to a close friend, Earl’s father served in the military and died around World War II, but it was not something Earl ever spoke about.1 In his early childhood, Earl moved to Berkeley, California, where he was raised by his mother, Rosalie (née Halligan), and stepfather, David Tucker, who worked as a longshoreman.

Robinson attended Longfellow School and Burbank Junior High, honing his baseball skills on the sandlots of San Pablo Park, located across the street from his home on Ward Street. “Robbie,” as friends called him, demonstrated both superb athleticism and strong character from an early age. He was known as an “enforcer” and would stand up to bullies when needed, but he also possessed a sensitive side. Once, Robinson was among a group of boys shooting the bull on the outfield grass at San Pablo Park. One of them, a Japanese American named Pete Domoto, was asked about World War II and the Japanese internment camps, an uncomfortable subject that was generally avoided at the time. Robinson protectively interjected that Pete did not have to talk about it. The incident sparked a bond between Earl and Pete, who quickly became best friends.

Robinson was a three-sport athlete at Berkeley High, where he also thrived in academics and was involved in student government. He was a starting defensive end for the football team his sophomore year, but he injured his knee and gave up the sport on the advice of his baseball coach. It was on the baseball diamond and basketball court where Robinson starred. He was a three-time Alameda County Athletic League All-Star as a first baseman and outfielder, twice teaming with future big-leaguer Ernie Broglio. As a guard for the Berkeley cagers, Robinson earned All-County honors. His athletic accomplishments inspired Jim Scott of the Berkeley Gazette to bestow him with the nickname “The Earl of Berkeley.”

Robinson was not afraid of a fight or to stand up to authority. In one instance during high school, Robinson was swimming with other students when he heard the track coach say something that he considered racist. Robinson pushed the coach into the pool, earning himself a suspension. “He was a bit ahead of his time,” recalled Domoto. “Most of us were not going to challenge authority in that way.”2

In the fall of 1954, Robinson enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley on an academic scholarship and majored in speech. He quickly became a baseball and basketball standout for the Golden Bears. Robinson hit .460 as a center fielder for Cal’s undefeated freshman nine and impressed Washington Senators manager Chuck Dressen, who called him “the best young physical specimen playing baseball I have seen out here in the West.”3

As a sophomore, the 6-foot-1, 192-pound Robinson was described by renowned basketball coach Pete Newell as “one of the finest natural athletes I have ever seen and one of the most coachable youngsters I have ever had.”4 Besides his athletic prowess, Robinson also had a reputation as a sharp dresser. “He had two bedrooms – one for him, and one for his clothes,” recalled roommate Joe Kapp, who played quarterback for the Golden Bears and later in the National Football League.5 At Kapp’s urging, Robinson took on the role of Lead Yell Leader, enthusiastically firing up the Cal faithful during football games.

Though Robinson formed close bonds with his Cal brethren, he was the subject of racial slurs and taunts from opposing teams. “There was a baseball game against USC when they were yelling some really ugly things at him while we were doing fielding drills before the game,” recalled teammate Bob Dalton. “So, he started firing balls into their dugout … Robbie didn’t hear another word the rest of the game.”6

Robinson played shortstop as a junior in 1957 and helped carry the Golden Bears to a conference title and ultimately the College World Series, where Cal defeated Penn State for the school’s second national championship. Robinson, named an All-American, was considered a “can’t miss” prospect and had all 16 major-league teams yearning for his services. Scouts were impressed by his quick wrists. “This kid can wait until the ball’s almost in the catcher’s mitt before swinging,” said Detroit Tigers scout Bernie DeViveiros. “He’s got good power too, and anybody who has seen him on the basketball court knows what a tremendous competitor he is.”7 Several teams offered bonuses, including a lucrative $60,000 bid by the St. Louis Cardinals.8

Robinson reached out to Jackie Robinson (no relation) and Sammy Davis Jr. for advice on whether to turn pro or return to college for his senior year. “While neither told him outright to turn down the bonus and continue his education as a speech major at Cal, both reminded him that his big ambition has always been to earn his UC degree,” reported the Oakland Tribune.9

Earl ultimately made the decision to return to Cal and served as team captain for the basketball team, leading the Golden Bears to a third consecutive Pacific Coast Conference title. He received all-conference honors for third time, earned a spot on the all-coast team for the second time, and was named his team’s Most Inspirational Player. Cal advanced to the Elite Eight in the NCAA tournament, where they were eliminated by Elgin Baylor and Seattle University. Robinson finished his college hoops career with 882 career points, ranking in the top five in Golden Bears history at the time.10

In the spring of 1958, Robinson decided to pursue a path in professional baseball on the advice of Newell, who was also an assistant baseball coach at Cal. Newell felt that Robinson’s chronic knee and elbow problems could jeopardize his earning potential if he delayed.11 The Pittsburgh Pirates paid several visits to Robinson’s home in hopes of signing him, but in the end the Los Angeles Dodgers won out. Scout Bill Brenzel, a former big-league catcher and Oakland native, had been bird-dogging him since high school.12 Another connection which may have given the Dodgers a leg up was that Brenzel and Cal coach George Wolfman had both played for the Mission Reds of the Pacific Coast League (PCL) in the 1930s, and Brenzel’s son was Robinson’s Bears’ teammate.

At the time, African American ballplayers were offered less lucrative deals than their white counterparts. Robinson enlisted the help of Cal law professor Adrian Kragen to negotiate his contract, resulting in a handsome $60,000 bonus with a three-year major-league pact at a graduating pay rate starting at $7,000 and escalating to more than $10,000 in the third year.13 Eleven years after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier, Earl became the first African American to receive a bonus contract.

Two days after signing, Robinson flew to Vero Beach, Florida, to join the Dodgers for spring training. He broke camp with the Montreal Royals of the Triple-A International League to begin the 1958 season but struggled, posting a .161 batting average in 56 at-bats with seven errors in his 18 games at shortstop. On May 23, he was optioned to the Green Bay Bluejays of the Class B Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League, where he joined a lineup that included Frank Howard. Green Bay manager Pete Reiser echoed the sentiments of many sportswriters who noted a striking resemblance between Earl and Jackie Robinson. “He walks like him, talks like him – and I hope he can play something like him,” said Reiser.14 The comparisons were not just an illusion of outgroup homogeneity; famed African American sportswriter Wendell Smith also wrote about their physical similarities.15 In 98 games with Green Bay, Robinson hit a respectable .254 and accumulated 33 extra base hits, including 10 home runs.

In September 1958, Robinson joined Howard, Jim Gentile, and Ron Fairly as a talented crop of players the Dodgers called up to close out the season. It had been a disappointing inaugural campaign out west for the former Brooklyn ballclub, which was fighting to stay out of the National League cellar.

Robinson made his major-league debut versus the Philadelphia Phillies on September 10 as a defensive replacement at third base. The next day, he was in manager Walter Alston’s starting lineup, hitting seventh in the order. In the top of the fifth inning, Robinson recorded his first career base hit, a single off Phillies starter Bob Conley, who was making his big-league debut. Robinson appeared in eight September contests, recording three safeties in 15 at-bats while playing flawlessly in six games at third base. After the season, Robinson re-enrolled at Cal to complete his degree and married the former Lillian Rita Holford. Their union would result in three daughters: Michele, Monica, and Mia.

In 1959, the Dodgers farmed out Robinson during spring training to the St. Paul Saints of the Triple-A American Association. Just 22, he was the youngest player on the team and showed continued improvement. Splitting time between third base and outfield, Robinson posted a .261/.333/.401 slash line in 500 plate appearances. He was among the minor-leaguers the Dodgers called up that September, but the team was in a tight pennant race and found no playing time for the inexperienced youngster.16

Robinson was assigned to the Spokane Indians of the Triple-A PCL for the 1960 campaign. He played right field, making up one-third of a talented outfield that included Fairly and Willie Davis. Robinson (.275, 12 homers, 79 RBIs) posted solid numbers but was overshadowed by even more impressive showings from Fairly (.303, 21 homers) and Davis (.346, 12 homers). Just like the year before, Robinson joined the big-league club in September but did not see action. With a bevy of talented young outfielders and veterans Duke Snider and Wally Moon in the fold, Robinson had become expendable. In December, the Dodgers sold him to the Baltimore Orioles for $50,000.17

Robinson went to spring training in 1961 looking to crack an Opening Day roster for the first time. He struggled early on in Grapefruit League play, recording only three hits in his first 22 at-bats.18 Even though Robinson was allowed to stay at the McAllister Hotel in Miami with his teammates, he voluntarily segregated at an all-Black hotel in Miami, where he felt, in his words, “more comfortable.” The only other African American player in camp, Mickey McGuire, did the same.19 Wendell Smith, a civil rights activist and mentor to Jackie Robinson, was critical of Earl for this decision in a Pittsburgh Courier column.20

Robinson improved his standing with the Orioles by going 3-for-4 with a pair of home runs and six RBIs in an April 2 exhibition against the White Sox.21 The righty hitter made the club as part of an outfield platoon with lefty swingers Whitey Herzog, Russ Snyder, and Gene Stephens.

Robinson, the 15th player of color to appear with the Browns/Orioles franchise, made his first start of the season on April 15 against Minnesota Twins lefty Chuck Stobbs. In his first at-bat as an Oriole, Robinson hit a two-run triple, finishing the game 2-for-3 with a walk and three RBIs. After another two-hit effort versus the Yankees on April 23, Robinson endured a 4-for-42 slump and saw infrequent playing time. Through June 18, he had started only 11 of Baltimore’s 65 games and his average had plummeted to .140.

Robinson’s fortunes turned on June 20 in Minnesota. He doubled in his first at-bat and came around to score on Brooks Robinson’s two-out single. With the Twins leading, 4-1, in the top of the ninth, Earl, who had singled in his second at-bat, came to the plate with two men on and one out. He redirected a pitch from Jack Kralick 390 feet into the right field bleachers for a game-tying three-run home run, the first of his career.22 However, Julio Bécquer stole Robinson’s thunder in the home half of the ninth with a pinch-hit homer to give Minnesota a 5-4 victory.

Following his first round-tripper, Robinson went on a hot streak, reaching base in each of his next 15 starts. His name began appearing in the Orioles lineup more regularly. Between June 20 and August 31, Robinson started 30 games and produced an impressive .342/.444/.642 slash line, with eight home runs and 22 RBIs. “He has as much power as anyone in the league when he connects solidly,” praised manager Paul Richards.23 Robinson would have seen more action, but a pulled groin muscle suffered running to first base at Griffith Stadium kept him out for 10 games in July. Later in the season, he hurt his back when he went to sit on a chair in the locker room and missed, falling on the concrete floor.24

Robinson was playing right field versus the Yankees on September 26 when Roger Maris tied Babe Ruth’s single-season record by crushing his 60th home run into the upper deck at Yankee Stadium. The ball caromed back on to the field and was retrieved by Robinson. “When the ball came back on the field I said, ‘I’m gonna keep this sucker,’ Robinson later said. “The umpire said, ‘Robinson, give me the damn ball before I toss you from the game.’ So, I did.”25 Forty years later, film director Billy Crystal called Robinson to ask him about that day in preparation for shooting the movie *61.26

Baltimore finished 1961 with 95 wins, good for only third place behind the Yankees (109) and Tigers (101). Robinson batted .268 in 96 games, with eight homers, 30 RBIs, and an OPS+ of 119. Of interest, he hit .312 on the road versus only .191 at Memorial Stadium. Half of his home runs came against the Twins, whom he terrorized with a .424 (14-for-33) average. He spent his offseason in Berkeley working on a master’s degree in analytical speech and stayed in shape by playing in a men’s basketball league.27

Robinson, 26, signed a $10,000 contract to return to the Orioles in 1962. Twenty-year-old Boog Powell emerged to capture the starting left field job, joining Jackie Brandt in center field, and leaving Robinson, Herzog, and Snyder to battle for playing time in right. Robinson had an excellent camp, leading the Birds with 16 RBIs.28 The team broke camp with Robinson poised to serve as the primary right fielder. He started 11 of the first 19 games but displayed “erratic” defense and was picked off first base by Twins catcher Earl Battey with Baltimore trailing, 8-4, on May 3.29 After his poor start, Robinson was relegated to a platoon role.

On May 13, the Orioles hosted the lowly Senators at Memorial Stadium for a Mother’s Day matinee. The teams were knotted at two runs apiece heading to the bottom of the ninth inning. Robinson led off and drove Marty Kutyna’s first pitch down the left field line. When the ball sailed over the yellow line and landed in a triangular space just below the foul pole, the umpires – citing the ballpark’s ground rules – called it a home run.30 As Robinson and his teammates headed to the showers, the Senators went berserk, arguing unsuccessfully that the ball was foul. The walk-off shot was Robinson’s first and only homer of the year.

Two days later, Robinson doubled twice against the Angels, raising his average to .264. He then started only one game in the next six weeks after developing a sore elbow that hampered his throwing. X-rays showed bone chips and surgery was considered, but ultimately the operation was deferred, a decision that Robinson would regret.31 On June 26, Baltimore assigned him to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings of the International League to make room for catcher Gus Triandos.

The subtraction of Robinson left the Orioles as the only major-league team without an African American player, a fact which led to criticism of the franchise. Such opprobrium was unjustified in the eyes of Smith, who pointed out the Orioles’ reputation for racial tolerance and equity relative to other teams.32 Team president and general manager Lee MacPhail insisted the transaction had nothing to do with race. “By sending him to Rochester we hope we will be able to salvage something out of a so-far disappointing season,” said MacPhail.33 Robinson’s balky elbow delayed his debut with Rochester until July 26, when he volunteered to come off the disabled list to replace the team’s injured first baseman, Cal Emery. Robinson appeared in only nine games for the Red Wings that season, recording four hits in 16 at-bats. His frustration boiled over in early August when manager Clyde King lifted him for 46-year-old pinch-hitter Luke Easter in an RBI situation. Robinson responded by destroying a chair in the clubhouse, drawing a fine from King.34 After Rochester’s season wrapped up, Robinson returned to California and underwent surgery to remove the bone chips from his right elbow, including one “the size of a half-dollar.”35

Robinson was passed over by other teams during the winter meetings draft and invited back to the Orioles’ big-league camp in Miami for spring training in 1963. Despite the elbow operation and isometric exercises to build his arm strength, he remained in pain when he threw or swung a bat. While playing outfield in spring training games, he had to lob the ball back to the infield. “It’s not satisfactory, and it’s going to cost me,” said a discouraged Robinson. “What can I do though, I felt last year that door had opened. Now it’s slammed shut.”36

The Orioles sent the dejected outfielder back to Rochester, where he spent the season trying to build up his arm strength. By August, he estimated that his elbow was still at only 75 percent.37 Nonetheless, he played in 108 games and hit a productive .262/.339/.442 with eight home runs and 42 RBIs for the Red Wings. Darrell Johnson, who had replaced King as manager, was impressed by Robinson as a player and person: “Watch him in center. He’s all over the place locking up line drives … and his attitude is simply ideal.”38

Robinson returned to Rochester for the 1964 season and showed no ill effects of the sore elbow that had hampered him for the better part of two years. At age 27, he was still in the prime of his career, but there was younger talent in the fold for the Orioles. Sam Bowens ascended from Triple-A to win Baltimore’s starting right field job, and the organization promoted 20-year-old phenom Paul Blair to Rochester, forcing Robinson to left field. Robinson had his finest professional season statistically, posting a .307/.363/.516 line with 11 home runs in 73 games for the Red Wings. Baltimore’s brass took notice and promoted him to the majors on July 20, replacing light-hitting Gino Cimoli. The Orioles owned the majors’ best record at the time, but the White Sox and Yankees were both right on their tailfeathers.

Robinson made an immediate impact for manager Hank Bauer’s club, hitting .352 (19-for-54) in his first 17 games. The Orioles won 13 of his first 16 starts and had cruised to a 73-43 record at the end of play on August 14. Robinson was not able to sustain his torrid pace but wound up with a respectable .273 average, three homers, and an OPS of .710. The AL race remained tight to the bitter end with the 97-win Orioles again finishing in third place, two games behind the pennant-winning Yankees.

Despite his strong showing, Robinson was demoted to Rochester after the season. He was one of five minor-leaguers invited to big-league camp in 1965 but being expunged from Baltimore’s 40-man roster made it clear where he stood on the team’s depth chart. His standing was further cemented by a lack of playing time early in Grapefruit League play, prompting Robinson to request a trade to the PCL to be closer to family (he and his wife had two daughters at the time). “It’s gotten to the point where, if I can’t help a big-league club soon, I’ve got to begin thinking about a career in something else,” Robinson told reporters.39 He got his wish on April 3 when Baltimore traded him to the Triple-A Salt Lake City Bees, the Chicago Cubs’ PCL affiliate, in exchange for outfielder Billy Ott. Robinson spent the entire season with the Bees and posted a .257/.364/.386 slash line with nine home runs and 35 RBIs in 116 games.

The Cubs made Robinson an offer to return to the organization for the 1966 season, but he found the proposal unappealing and decided to hang up his cleats.40 He finished his big-league career with a slash line of .268/.340/.425 and an OPS+ of 109 in 476 plate appearances over 170 games. He clubbed 12 career home runs, tallied 44 RBIs, and stole seven bases in 12 attempts. Though his career was relatively short – amounting to nearly the equivalent of one full big-league season – Robinson accumulated a 2.3 WAR.

During his baseball career, Robinson had spent his off-seasons substitute teaching in the East Bay, worked for the Oakland Recreation Department, and served as a part-time assistant for the Cal basketball team under coach Rene Herrerias. These experiences helped him transition to the next chapter of his life. In the spring of 1966, Robinson accepted a position at Merritt College in Oakland, becoming the first African American to coach basketball at a California junior college. His role also involved counseling high school graduates at the East Bay Skills Center. After one year at Merritt, he spent a year coaching at Laney – another junior college in Oakland – before returning to his alma mater to pilot the Cal freshmen during the 1968-69 season.

Robinson earned his doctorate in education and had a long tenure teaching speech and communications at Laney, where he served a stint as department chair. In 1981, the professor was hired by the Oakland Athletics to serve as Director of Special Projects, a role that involved community relations work. Robinson continued to teach at Laney, and one of the A’s star players eventually became his pupil.

Robinson had first met Rickey Henderson in the 1970s through a friend, scout J.J. Guinn, who discovered Henderson when he was a raw talent at Oakland Tech. After Henderson concluded his historic career and was elected to the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Guinn sent Henderson to Robinson for help with his induction speech. The 50-year-old Henderson attended Robinson’s class at Laney alongside typical college students in their late teens and early 20s. For several weeks, Henderson completed every assignment Robinson gave the class, including giving speeches in the middle of campus, where pedestrians, birds, and airplanes served as potential distractions. “Being exposed to those elements helped take away Rickey’s anxiety,” said Robinson in 2014.41 After his final speech in front of the class, Henderson got a standing ovation and went to Cooperstown a confident public speaker.

Robinson later taught English at Castlemont High School in Oakland. He was vice president with the Oakland Zoo’s board of trustees and served on the board of directors for the Cal Alumni Association, South Berkeley YMCA, Oakland Police Athletic Association YMCA, and Oakland Boys and Girls Club. His athletic accomplishments were recognized with enshrinement in Cal’s Hall of Fame in 1988 and induction into the Pac-10 Hall of Honor in 2010. Robinson received the Pete Newell Career Achievement Award from Cal in 2011.

Robinson went into cardiac arrest twice in 2013 and was diagnosed with end-stage heart failure. He required a prolonged hospitalization before entering hospice care. When his insurance coverage for hospice ran out and he and his fifth wife, Wilhelmina, were left footing the bill, former Dodgers owner Peter O’Malley chipped in, Major League Baseball’s Baseball Assistance team made a sizable contribution, and his former Cal teammates covered the rest. In his final days, Robinson enjoyed visits from Tommy Lasorda, Bill White, and a slew of friends and former teammates.

Earl Robinson died on July 4, 2014, in Fountain Valley, California, at the age of 77. His ashes were interred at Rolling Hills Memorial Park in Richmond, California.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to Dr. Pete Domoto for sharing memories and stories about Robinson. This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Malcolm Allen and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Phone interview between Pete Domoto and the author, July 9, 2022.

2 Domoto interview.

3 Paul Zimmerman, “Sportscripts,” Los Angeles Times, February 28, 1956: 77.

4 Zimmerman.

5 Martin Snapp, “Going to Bat for Earl Robinson: ‘We’ve Got to Do Something to Help Robbie,’” California Magazine, April 11, 2014, https://alumni.berkeley.edu/california-magazine/online/going-bat-earl-robinson-we-ve-got-do-something-help-robbie/, accessed June 29, 2022.

6 Snapp, “Going to Bat for Earl Robinson: ‘We’ve Got to Do Something to Help Robbie.’”

7 Emmons Byrne, “Stengel Will Back Martin,” Oakland Tribune, June 6, 1957: 58.

8 Scott Baillie, “Athlete Earl Robinson Also a Cheer Leader,” Times-Advocate (Escondido, California), December 11, 1957: 13.

9 “Robinson to Leave for L.A. Camp, Sees Rough Road,” Oakland Tribune, March 18, 1958: 43.

10 “Cal Great Earl Robinson Passes Away,” https://calbears.com/sports/2014/7/5/209540971.aspx, accessed June 27, 2022.

11 Domoto interview.

12 Bob Brachman, “Cal’s Robinson Takes $60,000 Dodger Bonus,” San Francisco Examiner, March 18, 1958: 29.

13 Brachman.

14 “Bluejays get Robinson; Catchers Out,” Green Bay Press Gazette, May 22, 1958: 41.

15 Wendell Smith, “What a Difference a Name Makes,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 3, 1961: 34.

16 “Earl Robinson Scheduled to Join Dodgers,” Oakland Tribune, September 2, 1959: 53.

17 Douglas Brown, “Robinson Purchase from L.A. Official,” Evening Sun (Baltimore, Maryland), December 13, 1960: 28.

18 Jim Elliot, “Earl Robinson Powers Birds’ Big Inning with Grand-Slam Home Run,” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 1961: 15.

19 “No Racial Problem for Birds in Florida,” Baltimore Sun, November 16, 1961: 44.

20 Smith.

21 Jim Elliot, “Earl Robinson Powers Birds’ Big Inning with Grand-Slam Home Run,” Baltimore Sun, April 3, 1961: 15.

22 Jim Elliot, “Earl Robinson’s Blast in Final Inning with Two on Ties Contest,” Baltimore Sun, June 21, 1961: 19.

23 Jim Elliot, “Birds ‘Still’ in Flag Race,” Baltimore Sun, July 5, 1961: 17.

24 Clifford Evans interview with Earl Robinson, 1962, SABR Oral History Collection, https://sabr.org/interview/earl-robinson-1962/, accessed June 10, 2022.

25 Alex Scordelis, “Rickey at the Mic,” September 5, 2014, https://www.vice.com/en/article/bmea7v/rickey-at-the-mic, accessed June 27, 2022.

26 Domoto interview.

27 Tommy Fitzgerald, “Making Herzog Healthy,” Miami News, March 31, 1962: 9.

28 Lou Hatter, “Hurting Physically, Orioles’ Robinson is Most ‘Unhappy Fella,’” Baltimore Sun, March 17, 1963: 130.

29 Lou Hatter, “Bird Faults are Obvious,” Baltimore Sun, May 5, 1962: 19.

30 Jim Elliot, “E. Robinson Belt Starts Hot Dispute,” Baltimore Sun, May 14, 1962: 19.

31 Hatter, “Hurting Physically, Orioles’ Robinson is Most ‘Unhappy Fella.’”

32 Wendell Smith, “Sports Beat,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 28, 1962: 20.

33 “MacPhail Insists He’d Hire Qualified Negro Players,” Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1962: 22.

34 Bill Vanderschmidt, “Wings Trip Vees Twice, Sweep Series; Open Two-Week Road Trip Tonight, Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), July 30, 1962: 22.

35 Hatter, “Hurting Physically, Orioles’ Robinson is Most ‘Unhappy Fella.’”

36 Hatter, “Hurting Physically, Orioles’ Robinson is Most ‘Unhappy Fella.’”

37 George Beahon, “Earl Robinson’s ‘Bad Attitude,’” Democrat and Chronicle, August 4, 1963: 56.

38 Beahon, “Earl Robinson’s ‘Bad Attitude.’”

39 Lou Hatter, “E. Robinson Wants Out,” Baltimore Sun, March 24, 1965: 25.

40 Dave Newhouse, “Robinson-Simpson Rivalry in Oakland,” Oakland Tribune, March 22, 1966: 43, 47.

41 Scordelis.

Full Name

Earl John Robinson

Born

November 3, 1936 at New Orleans, LA (USA)

Died

July 4, 2014 at Fountain Valley, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.