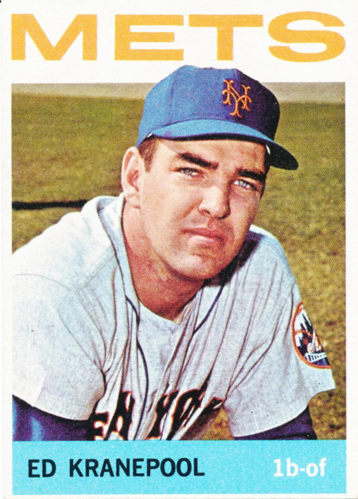

Ed Kranepool

It was a damp night at Shea Stadium in early August 1977. The last-place Mets, toiling through extra innings against the Los Angeles Dodgers, looked done for after the would-be National League champions took a 7-6 lead in the top of the 11th. But they managed to put runners at first and second with one out in the bottom of the inning. With light-hitting shortstop Doug Flynn due up next, manager Joe Torre signaled for the pinch hitter.

It was a damp night at Shea Stadium in early August 1977. The last-place Mets, toiling through extra innings against the Los Angeles Dodgers, looked done for after the would-be National League champions took a 7-6 lead in the top of the 11th. But they managed to put runners at first and second with one out in the bottom of the inning. With light-hitting shortstop Doug Flynn due up next, manager Joe Torre signaled for the pinch hitter.

Fans sensed what was coming, and what started as a low buzz of speculation among the stragglers of the crowd of just above 9,000 crescendoed into an all-too-familiar chant:

“Ed-die! Ed-die! Ed-die! Ed-die!”

Sure enough, the big lefty with the No. 7 on his back started taking practice cuts in the on-deck circle. Time for Steady Eddie Kranepool, pinch hitter extraordinaire, to play hero once again.

And once again, he came through, rapping out an RBI single to tie the score. The Mets would eventually win the game, 8-7, in the 12th on a single by Joel Youngblood, Kranepool’s clutch hitting reduced to a footnote. Business as usual in the life of a role player—and Kranepool was about as good a role player as they came. In 1974, he had set the all-time season record for pinch-hit batting average (over 30 at-bats) by compiling a mark of .486 (17 for 35) in those situations. In his career, he had 90 hits—including six home runs—off the bench.

Half a lifetime ago, though, Ed Kranepool was thought by some to be the next Lou Gehrig: a powerful left-handed slugging first baseman signed with much fanfare to a team just a borough away from where he was born and raised. When he fell far short of those weighty expectations, he might have disappeared, like so many other bonus babies who had failed to meet their potential.

But if Kranepool had one thing in common with the Iron Horse it was resilience. He refused to quit, and wouldn’t go away. Years later, he’d seen it all—from the Amazin’ly awful ’62 Mets to the Miracle of ’69, to the ’73 squad that had to “believe,” to the teams of the late ’70s that maybe didn’t so much believe. When he retired in 1979 after 18 seasons with the organization, he held just about every franchise record, and still holds some to this day. For better or for worse, he was the one constant for almost the entire first two decades of Mets history, and the fans in Flushing showered the last “original Met”1 with respect.

On July 28, 1944, 31-year-old Sgt. Edward Kranepool was machine-gunned down in Saint-Lô, France, leaving behind a three-year-old daughter, Marilyn, and a wife, Ethel, six months pregnant. The son, Edward Emil III, was born on November 8 of that year, in the Castle Hill section of the Bronx.

Faced with having to raise two small children herself, Ethel Kranepool survived on a military widow’s pension, and worked odd jobs to supplement her income.

“We were not an affluent family, obviously on a military pension, and I guess that’s why my days were spent in a playground as an athlete,” Ed Kranepool recalled. “When I was 10 years of age, I joined Little League, and that was the start of my baseball career.”

His neighbor and Little League coach, Jim Schiaffo, was about as close to a father as young Ed had.

“He was a good, good friend,” Kranepool said. “I thought when his wife died he and my mother would get married and they never did. He had two sons and he considered me the third son he never had. He loved baseball; he loved working with the kids.”

Schiaffo tirelessly worked with young Ed from an early age to improve his play. When he developed a habit of “stepping in the bucket”—bailing out the front foot on a pitch—Schiaffo placed a trough of water in the offending spot, so that every time his protégé stepped the wrong way, he’d end up with a wet foot. This literal interpretation of stepping in the bucket eventually worked.

“He would teach ways of how to hit and how not to hit and if you didn’t do it right, you paid the penalty,” Kranepool said. “He went to every one of my games after I graduated from Little League. He took a real interest.”

Kranepool, who grew up with images of the Yankees and Mickey Mantle’s heroics gracing the television, said that he never wanted to be anything but a baseball player. And he realized his talent early on. “I played every day of my life some kind of sport, preferably baseball or basketball,” he said. “We played stickball in those days in the street—I used to beat the big kids in stickball.” In Little League, he added, “I led the league in hitting three years in a row—I hit .700 every year. That’s gotta tell you you’re better than the average kid. Not to brag or anything.”

Most of the best players as children start off pitchers or catchers, and Kranepool starred on the mound; he still has the news clippings of those early feats. But when he was 11, he broke his left elbow rounding the bases.

“A guy on the opposing team stuck his leg out and I tripped over it on the concrete,” he said. “Medically, they didn’t set it properly and it just never healed properly. I performed well afterwards, but I never pitched as well as I did.”

He adjusted, instead, teaching himself to throw right-handed until the left arm was at full strength. When his velocity didn’t quite come back, he focused on playing first base and the outfield, positions where a powerful throwing arm isn’t necessarily top priority. And he never really had much trouble walloping the ball.

It also helped to live in the right school district: James Monroe High School, then, as now, a perennial city baseball powerhouse. A growth spurt his sophomore year helped him become a star basketball player, too, and as a 6-foot-3, over-200-pound senior he scored a then-school record 385 points (24 points per game) and was named to the All-New York City team. Several colleges, including St. John’s and North Carolina, offered him scholarships.

But basketball was more, for him, just a means to get in shape for the spring, and the baseball scouts were after Kranepool early. In three years with the Monroe varsity, he hit 19 home runs. Nine of them came his senior year, breaking a 1929 school record set by Hank Greenberg, who didn’t do so badly in the majors himself. Students nicknamed a large oak in right-center field “Eddie’s Tree,” after the long balls he hit in that direction. In 1962, Monroe made the Public School Athletic League (PSAL) finals, but lost, 6-5, to defending champion Curtis, a Staten Island school, in part because Kranepool, showing extreme hustle after a popup, had tripped over a garden hose someone had left out in right field and dropped the ball, allowing two runs to score. Kranepool had also come on to pitch in the seventh inning in that game, and recorded a scoreless eighth and ninth. Within weeks, he’d signed a major-league contract.

Nearly all the big league clubs had sent scouts to see Kranepool at some point or another. The Yankees would have been his first choice, naturally, and in the years before the First-Year Player Draft, prospects were free to sign with the highest bidder. There was more money to be had elsewhere. His physical education director had connections to the White Sox, and Greenberg, then the team vice president, had expressed some interest. But the expansion Mets, in search of its first home-grown star, recruited Kranepool relentlessly— they’d even invited him to cut classes and sit in the owner’s box at the team’s inaugural game at the Polo Grounds on April 13—and the lure of playing close to home was also an enticement.

On June 27, Mets scout Bubber Jonnard and vice president Johnny Murphy personally came to Kranepool’s home at 847 Castle Hill Avenue to work out the details. Ethel Kranepool, who was fully supportive of her son doing what he wanted to do, told the New York Mirror that she’d had a figure in her head about what she thought would be a fair offer when Murphy asked her son what he thought he should get. “When he came out with the identical figure I had in mind, I was stunned,” she said.2

“We hashed it out; it was a numbers game,” Ed Kranepool said. “Did I get the best contract? Probably not. Money wasn’t the only thing—I just wanted to play somewhere. There was an incentive clause; I get a bonus to get to the major leagues; if I had an agent, they would’ve not reduced it a bit.” But, he added, “It was more money than I ever expected in my life.” He signed the contract on the kitchen table.

For any 17-year-old kid nowadays, the number would have been somewhat staggering; in 1962 (before inflation and multimillion-dollar free agency), it was flat-out overwhelming: an $80,000 bonus, another $1,000 if he reached Double A, another $3,000 for Triple A, another $7,500 for the major leagues. He would hit them all by the end of the season. After the government swallowed half the contract, Kranepool invested the rest in a white T-bird convertible and an eight-room split-level in White Plains he shared with his mother.

Kranepool immediately flew out to Los Angeles—his first plane ride—to join the Mets, who were facing the Dodgers on June 30. His first day in a Mets uniform was only a harbinger of what his experiences would be in those early years with the team, as he watched Sandy Koufax no-hit his new teammates. Kranepool, who would eventually play on the losing end of three no–hitters in his career,3 might have made it four had he gotten in the game that day, as manager Casey Stengel went to the bench late in the game, but passed over the rookie in favor of Gene Woodling.

“I remember saying ‘thank God,’ to myself,” he recounted in his 1977 instructional, Baseball, written with Ed Kirkman. Kranepool had “wanted no part of the Dodgers lefty.”

After one week of riding the bench as a uniformed spectator, Kranepool was farmed out to Triple-A Syracuse for seasoning. But after struggling at the plate there, he was demoted to Class-A Knoxville (a Tigers farm club) in mid-July, and Class-D Auburn a week later. With Kranepool batting somewhere better than .340 at Auburn and, the Mets, on their way to shattering all kinds of records for futility with a 120-loss season, decided it was time to recall the promising prospect to the big-league roster on September 12. Kranepool’s first major league appearance came on September 22 (loss No. 116) against the Cubs, relieving Gil Hodges at first base in the seventh inning, and grounding out in his only at-bat in the eighth. A day later, in the Mets’ final home game (a win), he started at first base, and sliced a double down the left-field line in the eighth for his first major league hit.

As the 1963 season dawned, Kranepool, who had played winter ball in Florida in the months between, had reason to be hopeful he would be on the roster to stay. The New York writers were certainly hot on the Mets’ boy wonder, and manager Casey Stengel was spouting comparisons to Mel Ott, the Giants’ Hall of Famer who had also started at the Polo Grounds as a teenager. Young women from all over the country would flood his locker in those early years with love letters and marriage proposals. And Kranepool, who started at first base and the outfield early in the season and hit his first home run on April 19, could certainly be cocky about reports of his apparent maturity at such a young age. When Duke Snider, in the twilight of a Cooperstown-bound career, happened upon Kranepool slapping balls up the middle and to left field during batting practice, he reprimanded him to pull the ball to right, like a proper left-handed hitter should. Kranepool, who’d been specifically instructed by Stengel to spray the ball to the opposite field that day as a way of working on his timing, snapped back at his elder teammate, “You’re not going so good yourself.”

Part of Kranepool’s problem was that, in the days before all big league teams regularly employed hitting coaches, he never learned how to hit properly. “I was aggressive, very competitive. I would swing at balls I couldn’t hit, being young and anxious, and I would get out,” he said, adding that even though he always had good hand-eye coordination, “My eyes probably went against me…When I swung the bat at a ball, I hit it; I didn’t strike out. When a pitcher throws the ball that’s not in the hitting area, I’d hit a ground ball to second base, first base, and get out. Better hitters swing and miss at good pitches, so when they do make contact, it goes.”

Kranepool continued to slump, and, with his average down to .190 by early July, he was sent to Triple-A Buffalo, where he batted .310 with five home runs. He was recalled in early September, and started out at a 9-for-20 clip. He finished the year batting .274 in September (17-for-62) to lift his season average to .209. He reported to spring training in 1964 again confident he would remain in the majors, but again, things soured fairly quickly.

On his third day in Florida, he pulled his left hamstring running out a grounder to first. “Who ever heard of a 19-year-old kid pulling a muscle?”4 Stengel barked angrily to the media, intoning that if Kranepool had reported to camp in better shape, he wouldn’t have gotten hurt. Kranepool also took criticism, mainly from the press, for not running fast enough, and not hustling on the basepaths.

But Kranepool never had anything bad to say about Stengel. “In the baseball world, he gave me as much guidance as he could,” he recalled. “If I messed up, he didn’t expose me, he tried to help me.”

On May 13, batting .139, Kranepool was sent back to Buffalo. He cried. But after two weeks of batting .352 with three home runs, he was recalled to the parent club. Following a doubleheader at Syracuse on May 30, he hopped an early-morning flight to Newark Airport and cabbed it to Shea Stadium, the Mets’ brand-new ballpark, to start both ends of a sold-out 1 P.M. doubleheader against the Giants that day. The second game of the May 31 twin bill went 23 innings and finished a half-hour before midnight (the Mets lost both games). Kranepool was on the field for every out, marking a total of 50 innings of baseball played in two different cities, in two days.

“I wanted it to go a little longer,” he was often quoted afterwards. “That way, I could always say that I played in a game that started in May and ended in June.”

Kranepool started nearly every inning of every game at first base the rest of the season—with the exception of a two-week stretch in July when he sprained his ankle backing away from a pitch thrown by the Cardinals’ Ray Sadecki—batting .257 with 10 home runs and 45 RBIs in 420 at-bats for the season. Even though the Mets lost 100 games for the third straight season, they found themselves playing a role in the hotly-contested pennant race in a season-ending series with St. Louis. With the Cardinals leading the Cincinnati Reds by a half-game, the Mets miraculously took the first two games of the series to move the first-place teams into a tie entering the last day of the season. New York led in the fifth inning of the final game before St. Louis mounted a sizeable comeback; Kranepool’s foul popup in the ninth inning was the final out that clinched the Cardinals the National League pennant.

Banners unfurled at Shea that summer read, “IS ED KRANEPOOL OVER THE HILL?” and “SUPERSTIFF.” He hadn’t even hit his 20th birthday, and already he was being written off as a failure.

Kranepool had signed with the Mets partially because their situation seemed to promise an accelerated path to the Show (the Yankees, for one, had several prospects at first base who might have gotten in his way), but as the years went by, he slowly began to realize that may have been a grave mistake.

“It might not have been to my best advantage to get to the major leagues so fast,” said Kranepool. On an expansion team like the Mets, “you have [more] inexperience than on a better ballclub; a kid of 17 isn’t equipped to handle that pressure. If I was on a good ballclub, the pressure to handle that wouldn’t be so great. With the Mets, we were a bad ballclub. They said, ‘Ed’s going to lead them from a bad ballclub to the pennant.’ One player, even a Hall of Famer, can’t do that.”

History, in some ways, has overglamorized the Mets’ propensity for ineptitude before 1969—it wasn’t something they passively accepted in the way the fans unconditionally loved them for it. Ron Swoboda remembered Kranepool telling him of those early years, “We used to celebrate rainouts.”5 When asked once on a survey what his “greatest memory” of the 1962 season was, Kranepool wrote, “NONE.”6

“I still hit .255, .265, against Koufax or whoever, but everyone expected me to hit .350…I was always scrutinized by the fans in New York,” Kranepool said. “If you struggled in the minors, you struggled down in Podunk. They didn’t read about it in the papers every day.”

And there were social obstacles Kranepool hadn’t even considered. “My first roommate was Frank Thomas. He was 34; I was 17,” Kranepool said. “You tell me—what can you have in common with a 34-year-old? They used to go out, I couldn’t even drink!”

After the 1964 season, Stengel let go Tim Harkness, who had often started at first base the two previous years when Kranepool hadn’t, a further indication that Kranepool would finally be given chance to shine. When Warren Spahn joined the team the next spring, Kranepool voluntarily handed over his No. 21 jersey out of respect for the great pitcher who’d worn it his entire career. “I didn’t get a Rolex for it or a car; I just gave it to Warren,” he said. Kranepool picked up No. 7.

With a new number and a guaranteed roster spot, Kranepool came out swinging in 1965, leading the league in batting at the end of April. He was hitting .288 with seven home runs and 36 RBIs on July 7 when he found out he’d been selected to the National League All-Star team as the Mets’ lone representative. He ended up not playing in the game in Minnesota, but just making the squad at such a young age alongside a cast of future Hall of Famers was a thrill.

“I was looking to the right of me, and there was Willie Mays; to the left, Henry Aaron,” Kranepool said of what would end up being his lone All-Star experience. “I was the only one— I made the ‘Hall of Shame,’ I guess.”

Upon his return from the Twin Cities, Kranepool fell into a second-half slump, and ended up batting .253 with 10 home runs and 53 RBIs. As the season came to a close, he often platooned with Jim Hickman, too.

In 1966, he was again promised by new manager Wes Westrum (Stengel retired in the middle of the previous season due to a broken hip) that he would be the starting first baseman, but the Mets acquired righty Dick Stuart; Kranepool ended up platooning again, with Stuart (who batted .218 and was released in June), and a cast of characters including Hickman, Hawk Taylor, and Ed Bressoud. Kranepool finished the season with similar numbers to the previous year: .254, 16 home runs (which turned out to be his career high), and 57 RBIs.

In the winters of 1964 and 1965, Kranepool had taken courses at the Institute of Finance. He successfully passed the exam for his stockbroker’s license on his 21st birthday, the first day he was eligible. By early 1967, he had built up a steady clientele of around 160 accounts at the brokerage firm of Brand, Grumet & Seigel. He married a secretary from the firm, the former Carole Henson, just before spring training.

As one of only two licensed brokers in the National League at the time (pitcher and future U.S. Senator Jim Bunning being the other), Kranepool would often discuss the Mets’ ups and downs in terms of the boom and bust of the stock market. He would read The Wall Street Journal every day, and carry paperwork from the office with him on road trips. Sometimes, players would ask him for financial advice.

“During the World Series, the Dow-Jones wire carries the score every inning, plus the home runs and pitchers,” he mused at the time. “Wouldn’t it be great if the Mets got into the Series and I hit a home run that was flashed over the ticker along with the quotations? Boy, the office would go wild.”7 Kranepool had no idea just how prophetic those words would be.

The Mets still were finishing towards the bottom of the league in 1967 and 1968 (as Kranepool continued to platoon with a laundry list of names), but the hiring of manager (and ex-’62 Met) Gil Hodges in the latter season, and the infusion of new, young talent at the major league level showed signs that fortunes were about to turn around. Kranepool was maturing, as well—he and Carole had moved out to South Farmingdale, Long Island, and he became a father to Edward Keith Kranepool on March 2, 1969—and he was suddenly finding himself surrounded by teammates his own age. As the only player left who’d been part of the ’62 team, he had, oddly, become the seasoned veteran, in terms of service. (Al Jackson, an original Met, had been reacquired in 1968, but was traded away in the middle of the 1969 season.)

“Spring Training, Gil Hodges wanted you to lead by example,” Kranepool said of early 1969. “He built the ballclub around leadership. First, we had to get over .500—we never got to the .500 level before—it’s the only way to win the game. The team that makes the fewest mental mistakes does. We didn’t beat ourselves; we had good pitching and defense; we started to play well. We did get to .500, beat L.A. and San Diego, and went on a 10-game winning streak.”

The first-place Cubs swaggered into New York for a three-game series, holding a 5½-game lead in the newly created National League East division. In the opening game on July 8, Kranepool’s solo home run in the fifth had been Mets’ only hit off starter Fergie Jenkins until the ninth inning. After the Mets had rallied from a 3-1 deficit to tie the score in the bottom of the ninth—with Cubs center fielder Don Young having trouble with two fly balls—Kranepool singled to left field to drive in Cleon Jones for the winning run in front of a crowd of 55,000. The Mets would go on to win the series with Tom Seaver taking a perfect game into the ninth the following night. The Cubs, who had dismissed the Mets as an inferior team—third baseman Ron Santo said of the infield that day of Kranepool, Wayne Garrett, Al Weis, and Bobby Pfeil, “I wouldn’t let that infield play in Tacoma” —soon found that New York’s young team had the talent to overtake Chicago.

“That was like the turning point of the season,” Kranepool said. “When you sweep them”—the Mets actually lost the third game of the series, but went 5-2 against the Cubs the rest of the season—“you pick up a lot of ground in a hurry. We built up our confidence. That was probably my biggest hit.”

The Mets finished the year with a league-best 100-62 record and swept the Braves in the three-game divisional playoff to win their first pennant and face the 109-win American League champion Baltimore Orioles in the World Series. Though Kranepool played all three NLCS games against Atlanta—and batted .250—Kranepool was benched in favor of the right-handed-hitting Donn Clendenon for all but one of the Series’ five games (the only game started by a right-handed pitcher). Kranepool made it count, hitting a home run off Dave Leonhard in the eighth inning of Game Three. After 800 defeats8—most of which Kranepool had witnessed himself—the Mets were crowned world champions.

With the Mets the toast of the town, Kranepool and Ron Swoboda partnered up to do publicity for a resort in the Poconos. They also opened a restaurant called “The Dugout” in North Amityville, Long Island, in the offseason.

“We did it for a couple of years,” Kranepool said. “It was a tough business—a lot of hours, very time-consuming. It’s a business you have to be there for. We wanted to be at the restaurant for the people.”

Kranepool also took his place as the face of the Mets as their player representative at meetings for the burgeoning Players’ Association that fall. He was outspoken, never hesitant to call out superstars he felt were undermining the union’s goals. (Carl Yastrzemski, for example, was “nothing more than a yo-yo for American League president Joe Cronin,” he told the media.9)

“I wasn’t afraid to protect the players and attend the meetings and the associations,” he said of why the Mets chose him. “And the players, themselves, that doesn’t bode well for you, sometimes, when you’re speaking on behalf of the group, owners can take it as a bone of contention. I wasn’t afraid of getting traded, nor was I afraid of speaking out against others’ interests.”

When he negotiated his contract for 1970, despite having hit .238 and platooning with Clendenon at first base the previous season, Kranepool was one of the last holdouts (along with Swoboda), arguing for a raise on the grounds the he helped the team win the World Series. He got one, signing for $32,000 (up from $24,500 in 1969) in late February.

Where he would play was another story, though. The Mets retained four first basemen out of spring training, and three of them—Kranepool, Art Shamsky, and Mike Jorgensen—were left-handed. With Shamsky starting against right-handed pitching and Jorgensen going in as a defensive replacement—not to mention Kranepool and Hodges often butting heads—the writing on the wall was more than obvious.

Over the years, Kranepool’s name had often surfaced in trade talks. (A deal had almost been made to include him in a package to acquire Braves catcher Joe Torre before the 1969 season, for instance, and another potential transaction had him going to Philadelphia for Dick Allen.) But even later in the 1970s, when the Mets began dismantling the team that had won two pennants and a World Series, nothing ever materialized regarding Kranepool.

Part of it might have been favoritism. Team owner Joan Whitney Payson had taken a special liking to Kranepool, and he thought of her “like a grandmother.”

“If a trade came up—unless it was for Henry Aaron or something—she was not just going to give Ed Kranepool away. Donald Grant liked me also,” Kranepool said, referring to the team chairman. “I was very straight—I didn’t create any problems. If you talk to me, you may not like me, because I’m going to tell you exactly how it is. I don’t sugar-coat it.”

Nevertheless, Kranepool’s dwindling playing time and productivity nearly forced the Mets to give up on their once-prized investment. Through June 23, Kranepool had gone to bat a mere 34 times, with four hits (.118), none of which came in his 18 at bats as a pinch hitter. The Mets, looking to bring up outfield prospect Ken Singleton, asked for waivers on Kranepool; when no team claimed him, he was optioned to Triple-A Tidewater.

Thus, a mere eight months after winning the World Series, Kranepool began to consider walking away from the game forever. He still had his stockbrokerage business, after all, and his restaurant business, and other financial investments to get by just fine without baseball. But he wasn’t ready. Not to mention M. Donald Grant had promised him that he would return to the big league club if he performed well in the minors. “He was from the old school where a handshake meant something,” Kranepool said.

So Kranepool succeeded Tidewater, batting .310 with seven home runs in 47 games, and returned to the Mets on August 14. He finished with a .170 average (almost always as a pinch hitter) as the Mets finished third at 83-79.

Spring training 1971 seemed for Kranepool—in the words of coach and future Mets manager Yogi Berra—to be déjà vu all over again. He managed to secure a contract for the exact same salary as the previous season; he still was competing with at least four first basemen; he still doubted Hodges had much confidence in his abilities. Writers who’d called his demotion the previous season the end of an era were now forecasting this might be Kranepool’s final spring. The one difference was that this year, Kranepool felt he had nothing to lose; if he made the team, so much the better, but if not, perhaps he could play well enough that one of the other 23 teams would want him. Being sent down to the minors had been a humbling experience, and had caused Kranepool to shed much of the bitter conceit that had marked his earlier years.

“Gil Hodges and I had a different relationship after that,” Kranepool said. “I didn’t like him. I didn’t like Gil Hodges when I first played. When you’re on a bad ballclub, you get negative vibes around you. Certain things, he didn’t like what I did; I didn’t like how he handled me. When I got sent down and came back—I could’ve quit at that point—I did very well, and he learned to respect me, and I learned to respect him.”

Hitting seems to cure all ills, too, and in 1971, Kranepool put together perhaps his best season in the majors. His name hadn’t even been on the All-Star ballot because he hadn’t been expected to start before the season began, but he received numerous write-in votes from fans. He wasn’t selected, but he did finish the season tied for the club lead in home runs (14), and with a career high in RBIs (58), and what was then his highest batting average (.280). A bizarre brief dugout scuffle on May 26 with rookie Tim Foli—in which the hot-tempered infielder had taken offense at Kranepool’s refusal to throw groundballs to him during between-inning warmups after Foli had previously thrown a ball in the dirt in front of Kranepool, and wound up with a black eye—seemed like his season’s only blemish. Kranepool received a $10,500 raise the next season.

The Mets were stunned in spring training 1972 when Gil Hodges died suddenly of a heart attack. Many members of the team, Kranepool included, regarded him as the best manager they ever played for. “Strategically, fundamentally, he was a sound manager, knew the game, taught you how to win,” Kranepool said. “If he would’ve continued and not passed away, we would’ve won more pennants.”

About new manager Yogi Berra, Kranepool mused, “Yogi was a great guy, fun-loving, well-liked by the players. Very easygoing, but not the leadership Gil Hodges had. The inmates can’t run the asylum.”

Kranepool homered and knocked in three against the world champion Pittsburgh Pirates on April 15, the strike-delayed Opening Day of 1972, but by mid-season, he was struggling (and platooning) again. He finished batting .269 with New York again in third place.

With the Mets floundering around midseason of 1973, M. Donald Grant came into the clubhouse one day for a rare inspirational pep talk. Toward the end of his speech was when struggling pitcher Tug McGraw stood up and animatedly began yelling, “Ya gotta believe.” Grant left the room, thinking McGraw was mocking him. Kranepool was McGraw’s roommate at the time, and realized the potential for trouble.

“I said to Tug, as the player rep, ‘You better tell Donald Grant you didn’t mean anything, that you were endorsing what he was saying,’” Kranepool said. “We went outside the locker, Donald was there, and Tug stopped him and he apologized and everything was fine. It cleared the air. It was not a negative rant. And it became the rally cry of the team that year, ‘Ya gotta believe.’

“Mr. Grant, you have to realize, he was a pinstripe dresser: black-tie, pinstripe, Wall Street executive. He was very prim and proper like Mrs. Payson was. So when someone starts ranting and raving, he’s going to take offense. Tug, as my roommate, I was protecting him, because I didn’t want him to end up in the doghouse.”

The Mets—and McGraw—did turn it around that season, of course, taking the league championship with the lowest winning percentage of any team in history (.509), and narrowly losing the World Series in seven games to an Oakland A’s team on its way to three consecutive titles. Kranepool’s average dipped to .239 (he was sharing time with John Milner and starting some games in the outfield), and he started the decisive Game Five of the NL Championship Series in place of the injured Rusty Staub, driving in two runs with a first-inning single. In his appearances in the World Series, he was 0-for-3 pinch-hitting, though his groundball to first for an error in the ninth inning of Game Seven scored the Mets’ final run of the Series.

It might have been foreshadowing. Kranepool’s role as a starter was diminishing, as younger prospects were tried out at first base. In 1974, Kranepool was used frequently as a pinch hitter. For many players, transitioning from starting to pinch-hitting can be a warning sign that one’s days in baseball—or with a particular team—are numbered, but Kranepool seemed to fit right in.

“I was able to motivate myself to pinch-hit and perform,” Kranepool said. “I was trying to prove the managers wrong by not playing me, and I wound up very successful.”

Between 1974 and 1978, Kranepool batted .396 as a pinch hitter. He hit the .300 mark in a season twice in his part-time playing role in those years that included the occasional start at first base, in 1974 and 1975, the latter when he batted a career-high .323 (in 325 at-bats). Always willing to help the younger players coming up through the system, he even coauthored a book on baseball fundamentals in 1977, drawing from his own experiences from Little League all the way through the professional level; naturally, there was a chapter devoted to pinch-hitting.

His relationship with the Mets front office, however, slowly headed downhill. It started in 1975, with the death of Mrs. Payson. Kranepool was the only player at her funeral, and her death hit him hard. “She was the sweetest person you’d ever meet,” Kranepool said. “You had a lot of respect for her for who she was, not because she owned the ballclub.”

The new management fell to her daughter, Lorinda de Roulet, with whom Kranepool said he should have gotten along, but didn’t. Mrs. de Roulet wasn’t quite equipped to go from running social parties to running a corporation, and she preferred to rely on Joe McDonald, who’d become general manager in 1974, to make business decisions, instead of Donald Grant.

“I didn’t have a good relationship with Joe McDonald. I didn’t respect him. I didn’t like him; he didn’t know anything about baseball,” Kranepool said. “There were termites who ate away at the organization, and he was part of the termites. Donald Grant got blamed for it, but Joe McDonald was the one who made the trades.”

The sticking point in Kranepool’s disdain for McDonald arose from contract squabbles before the 1977 season. With the advent of free agency, players had more bargaining power and the ability to negotiate multiyear deals, and Kranepool said he needed some time to think over the figure McDonald had offered him.

“I live 30 minutes from Shea Stadium; as soon as I got home, the phone rang—he’d taken back the contract,” Kranepool said. “I said, ‘Joe how could you rescind the contract? I just got home!’ But that’s what he did. I cursed him out and used a lot of not-nice words I probably shouldn’t’ve been saying. And hung up.”

Kranepool alerted Grant of the situation, and the two met at Fahnestock & Company, Grant’s firm on Wall Street, where a phone call to McDonald confirmed Kranepool’s story. “Donald Grant said, ‘You got the contract, and you got an additional $10,000,’” Kranepool recalled. “It was with a handshake that I signed the contract in his office. A three-year contract. When it was up in ‘79, I knew Joe McDonald was not going to offer me a contract.”

As the Mets continued to tailspin back into their form of the early 1960s, Kranepool began hinting that 1979 would be his last year; the rift between him and Mets management was too deep, and he wasn’t getting very many opportunities to play—even as a pinch hitter—so his performance off the bench declined. And the fact that manager Joe Torre—at one time Kranepool’s roommate when the two were players—said little on his behalf, hurt even more.

“Joe Torre knew what my plans were and didn’t protect me at the end, and I never talked to him again,” Kranepool said. “Joe Torre knew the situation. Sometimes, you have to be a man and stick up for your friends. I was the one that was his right-hand man in the three years as a manager, and he knew he had to protect his own job: ‘Let Ed fend for himself.’ To me, that’s being a turncoat.”

Torre would say years later that letting Kranepool go was one of the hardest things he ever had to do.10

The final nail in Kranepool’s coffin came during the Mets’ final homestand, when the Mets chose to honor retiring Lou Brock of the Cardinals and did not even acknowledge that Kranepool was probably suiting up for the final time at Shea. He received a short notice in the mail that offseason detailing his release, but not even the original: a carbon copy of the note sent to his agent, Dick Moss. Kranepool filed for free agency, but it seemed more of a formality. After 18 seasons, 1,853 games, 5,436 at-bats, 1,418 hits (for a .261 average), and 118 home runs, he was through.

“I never knew I retired,” he said. “I went from one thing to another.” Kranepool had given thought to what he might do after his career was over; he had little interest in managing, but he felt he might be suited to work in the front office. Earlier that year, he had gotten wind from Charles Payson, Mrs. Payson’s widower, that the Mets might be up for sale, and Kranepool put together a group to buy the team, the package which he presented to Lorinda de Roulet that September.

“And then she put together her friends, her social group, and they bought the ballclub,” Kranepool said. New owners Fred Wilpon and Nelson Doubleday brought in Frank Cashen as the new general manager, and Kranepool left baseball for good.

“I left the Mets when I should’ve been on top, and ended out at the bottom,” Kranepool said. “I can’t have any harsh feelings for the Wilpons and the team.” 11

He unintentionally stirred up some minor controversy in 1986 when he appeared in a campaign commercial for friend and U.S. Senator Al D’Amato in a Mets uniform, causing the team to release an adamant statement that it did not take political sides.

For six years, Kranepool was also a spokesperson for Pfizer, traveling the country promoting diabetes awareness—a disease he learned he had developed the year he retired.

“That was the most fun I had working for a company, and they were a great company,” said Kranepool, whose activities included penning a cooking booklet, “Ed Kranepool’s Favorite Recipes for Diabetes Control,” in 1990. “It was not up for me to sell drugs; I just had to get awareness to the doctors and awareness to the public: ‘people can get checked,’ ‘be aware of the symptoms,’ ‘go to your doctor,’ ‘do what can be done for it.’

“Then, when I was taken off the medication, I had to give up the position at the company. The way they are, you give up the medication, you can’t be part of their team. I had to go back on insulin for a few years. The drug I was on wasn’t as effective anymore; I couldn’t endorse that pill.”

In 2004, he launched The Memorabilia Road Show, a traveling and online auction that collected pieces of memorabilia personally from players and or from their family members who needed a place to sell it, in turn giving the items a degree of authentic integrity that couldn’t otherwise be provided by a third-party dealer. Kranepool sold the company shortly after it opened, and it didn’t last long afterwards without him.

Kranepool currently works in credit card processing, soliciting businesses and retailers. “This is a business, knowing stores and establishments,” he said. “Being who I am gets the visibility to the decision-makers. It’s something that has to be done; it’s all who’s doing it.”

He does frequent charity work, of which much of the money gets directed toward diabetes and autism research. In 2008 he was honored by the Hagedorn Little Village School, for special needs children, in Seaford, Long Island. Similarly, in 2019, he was honored at the Thurman Munson Awards Dinner, which benefits the AHRC New York City Foundation helping people with developmental disabilities.

Kranepool and his wife, Monica, a real estate broker at Sotheby’s and mother of two whom he married in 1981, live in Nassau County. (He and Carole divorced.) His son, Keith, developed into a decent athlete—he’s 6-foot-7—but he never settled on one sport, and chose to pursue other interests. He works in electronics, and has two sons and a daughter. Monica also has four grandchildren. They own a custom-build power yacht from 2003, Meema On Deck.12

It was an incident on the boat in September 2016 that led to the discovery he was in kidney failure. On antibiotics for an infected cut on his left foot, he noticed he had trouble breathing.

“I was rushed to the hospital and I thought I was having heart attack,” Kranepool said. “The doctor said, ‘I have good news and bad news. The good news is it’s not your heart. The bad news is you need a new kidney.’”13

Reducing the dosage so that it wouldn’t further damage his kidneys spread the infection to the bone; eventually, all the toes on his left foot were amputated. A special boot has allowed him to walk unassisted.

Getting a transplant was another matter, as both age (operating on a diabetic in his mid-70’s is already risky) and time (as of 2019, over 113,000 Americans were on the wait list, which was about five years without a private donor) were working against him. Over the next two years. Kranepool sold off much of his Mets memorabilia to pay for medical expenses as he waited for a donor to come forward.14

“We hope we find a donor,” he said in a 2019 interview at Mets spring training. “I need a pinch hitter.”15

He managed to avoid dialysis, but his kidney function was at about 20% when someone finally came through in the clutch. Kranepool’s transplant took place on May 7, 2019. Less than a week later, he held a news conference from Stony Brook Hospital to express his gratitude toward the transplant donors—he was part of a paired exchange, his donor being the wife of another transplantee—and the medical professionals who handled him.

“I’ve been lucky to have a great team at home —my wife and family,” he said. “And also the Met organization. I’ve been with them since 1962. Those are the only two teams I knew up until that time. Now I have an extended team.”16

Postscript

Ed Kranepool died at the age of 79 on September 8, 2024.

Sources

All quotes from Ed Kranepool, unless otherwise noted, come from telephone conversations with the author on May 13 and 14, 2008. Statistics, unless otherwise noted, are from baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, and minors.sabrwebs.com. Special thanks to Gabriel Schechter, formerly of the National Baseball Hall of Fame Archives, from where much of this information was taken. Special thanks to the late Jim Plummer for his assistance in contacting Ed Kranepool.

Notes

1 As Kranepool was still in high school at the start of the 1962 season (he signed with the Mets in June), calling him an “original” Met is a bit of a misnomer; nevertheless, fans and writers alike associate him with that team, as he was on the Mets’ expansion season roster in September.

2 Irene Janowicz, “Woman In The Family,” New York Mirror, April 28, 1963.

3 He was thankfully spared another opportunity at a fourth when Ed Halicki no-hit the Mets on August 24, 1975, a game in which he did not play.

4 Arthur Daley, “Sports of The Times: The Boy Wonder,” New York Times, March 22, 1965.

5 Peter Golenbock. Amazin’: The Miraculous History of New York’s Most Beloved Team (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2002), 169.

6 Ed Kranepool file, National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

7 Joseph Durso, “Keeping Up With Kranepool and the Dow-Jones,” New York Times, March 7, 1967.

8 799 regular-season losses from 1962-69, plus Game One of the World Series.

9 Ken Rappoport. “Kranepool Takes Verbal Shots At Yastrzemski’s Stand On Reserve Clause.” Cortland Standard, January 30, 1970.

10 Ed Barmakian, “Cone Doesn’t Help Bid for Playoff Spot; Indians Make It an Unhappy Return,” Star-Ledger (Newark, New Jersey), September 16, 2000.

11 However, the relationship between Kranepool and the Mets became somewhat frosty in the wake of the Bernie Madoff scandal, which hit the Wilpons hard. Depending who is telling the story, Kranepool either allegedly offered to buy the team again, claiming he could run it better, or “had some words” with Jeff Wilpon after rumors surfaced he was connected to a group interested in buying the team. The Wilpons didn’t sell. See Wallace Matthews, “The Real Mr. Met Is Selling Off His Past and Coping With the Present,” New York Times, December 21, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2017/12/21/sports/baseball/mets-ed-kranepool-memorabilia-wilpon.html.

12 As of March 2019, the boat is up for sale.

13 Christian Red, “Beloved Mets Legend Ed Kranepool on Waiting List for Kidney Donor, Has Left Big Toe Amputated,” New York Daily News, March 2, 2017, https://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/mets/beloved-mets-legend-ed-kranepool-waiting-list-kidney-donor-article-1.2987486.

14 Kranepool claimed he didn’t need the money; he just didn’t “have space for it.” Matthews, New York Times.

15 “‘69 Mets Legend Ed Kranepool Joins Howie And Wayne,” WCBS-880 Broadcast, February 23, 2019, https://wcbs880.radio.com/media/audio-channel/69-mets-legend-ed-kranepool-joins-howie-and-wayne

16 Steven Marcus, “Ed Kranepool ‘Close to Normal’ After Kidney Transplant, His Doctor Says,” Newsday, May 13, 2019. https://www.newsday.com/sports/baseball/mets/ed-kranepool-kidney-transplant-1.30890095

Full Name

Edward Emil Kranepool

Born

November 8, 1944 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

September 8, 2024 at Boca Raton, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.