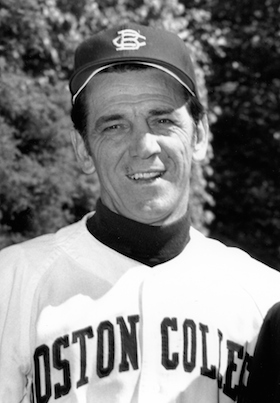

Eddie Pellagrini

In 1941, the book on 23-year-old Eddie Pellagrini was as a “good field, no hit” shortstop. “[He] may not hit as well as [others] but he’s certainly a fine prospect … ‘Pellagrini is a faster fielder than [most],’” said San Diego Padres player-manager Cedric Durst. It thus came as a surprise five years later when Pellagrini became the 22nd player (and first Red Sox) in history to hit a home run in his first major league at-bat. The right-handed hitter’s blast on April 22, 1946 provided Boston’s winning margin over the Washington Senators. Three days later Pellagrini was a single shy of the cycle in leading the Red Sox to a 12-5 win over the New York Yankees. “People forget [that],” he laughingly recalled years after. “[B]ut I didn’t hit very many homers after that.”1

In 1941, the book on 23-year-old Eddie Pellagrini was as a “good field, no hit” shortstop. “[He] may not hit as well as [others] but he’s certainly a fine prospect … ‘Pellagrini is a faster fielder than [most],’” said San Diego Padres player-manager Cedric Durst. It thus came as a surprise five years later when Pellagrini became the 22nd player (and first Red Sox) in history to hit a home run in his first major league at-bat. The right-handed hitter’s blast on April 22, 1946 provided Boston’s winning margin over the Washington Senators. Three days later Pellagrini was a single shy of the cycle in leading the Red Sox to a 12-5 win over the New York Yankees. “People forget [that],” he laughingly recalled years after. “[B]ut I didn’t hit very many homers after that.”1

In Boston’s next 11 games Pellagrini managed just four hits and one walk in 44 plate appearances, including 13 strikeouts, to earn a spot on the bench. Throughout the remainder of his eight-year career Pellagrini would serve primarily as a utility infielder. “I should have retired after those first [few] games,”2 he cracked. He remained an avid student of the game and, as the years passed, was not hesitant to share that knowledge. In a 1954 poll of baseball writers Pellagrini was anointed as one of the best tutors of young talent in the majors. Later this served him well when he launched a second career as the longtime Boston College baseball coach.

Edward Charles “Pelly” Pellagrini was born on March 13, 1918, the third of eight children (and the first boy) of Anthony and Mary (Gamalda) Pellagrini, in Boston, Massachusetts. His father emigrated from Italy around 1911 and two years later married Miss Gamalda, a New York native and child of Italian immigrants.3 Growing up less than four miles south of Fenway Park, baseball played a significant role in Pellagrini’s youth. In 1936 the high school senior served as captain of the Roxbury Memorial High School for Boys baseball team (he excelled at football and track and was an honor roll student as well). Pelly’s parents wanted him to go to Boston College but he was interested only in pursuing a career in baseball. Two years later Red Sox scout and future Hall of Fame inductee Hugh Duffy signed Pellagrini to a professional contract, presumably during a Fenway Park tryout (though he may also have been spied among the semi-pro circuits).

From 1938-1940 Pellagrini displayed some offensive promise in the low minors, but he showed less above Class C play (.257 in 456 at-bats). Just before the 1941 season the Red Sox sent him, pitcher Yank Terry and $12,000 to the San Diego Padres in the Pacific Coast League for 31-year-old hurler Dick Newsome. (A Class AA Red Sox affiliate as late as 1937, the Padres appear to have maintained a close relationship with Boston years afterward.) Under the direction of Cedric Durst, a former major-league outfielder, Pellagrini thrived, placing among the team leaders in most offensive categories. His success could not have been timelier. That year the Red Sox’ 34-year-old shortstop-manager Joe Cronin announced his plan to relinquish his middle infield position in favor of either Pellagrini or another budding prospect, Johnny Pesky.

The Sox’ 1942 spring camp competition between the shortstops proved friendly, eventually developing into a lifelong bond. As it happened, Pellagrini seemed to have the inside track for reasons other than field performance. When the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Pesky had a 1-A classification and appeared certain to be headed overseas. Pellagrini, classified 3-A (dependents), seemed a less likely candidate for war (since he did not start a family until 1946, it is believed his dependents were his elderly parents). This thinking was turned on its head in April when Pellagrini’s status was inexplicably changed to 1-A and Pesky prevailed in the shortstop competition. The Red Sox briefly considered carrying Pellagrini on the roster but chose instead to assign him to Louisville in the American Association, where he could get steady play before Pesky’s expected departure. This plan worked only until May 15 when Pellagrini was drafted into the US Navy. Pesky did not enter the service until 1943.

Pellagrini was assigned to the Great Lakes, Illinois Naval Training Station north of Chicago. where he stayed for over a year. The Station developed a splendid baseball team – the Great Lake Bluejackets – made up of professional players from all levels. They successfully beat local semipro clubs and upset several major league teams in local exhibitions. On May 30, 1943, a Pellagrini home run led the Bluejackets to victory over a Muncie, Indiana semipro club. A month later he was pacing the club in homers while tied with teammate and future Hall of Famer Johnny Mize – the club’s smallest and largest players, respectively – with a .463 batting average. In 1944, while Pellagrini was serving in the Pacific Theatre, he teamed with Mize and Pee Wee Reese to lead the 14th Naval District to a 9-0 win over a US Army All Star team. On October 13, 1945, 41 days after Japan’s formal surrender, Pellagrini earned his release from the service.

In 1946 the same Pesky-Pellagrini spring competition was established. Memories of The Needle’s superb debut season four years earlier, combined with an injury Pelly sustained in training camp, gave Pesky a decided edge. By mid-March the Red Sox began trying Pellagrini at third base. The hot corner was an open competition with no fewer than seven players manning the post during Boston’s pennant-winning season. But it was as a replacement at shortstop (after Washington Senators righty Sid Hudson hit Pesky in the head with a pitched ball) that Pellagrini made his aforementioned major league debut by hammering Hudson’s 2-2 delivery. “I still send Hudson a Christmas card every year,”4 Pellagrini joked decades later. Used sparingly through the season – he had just one at-bat over a 53-day stretch – Pellagrini earned eight more appearances at short and 14 at third. Despite the sparing play, on September 24 he was honored as the only homegrown player on the Red Sox and was given a new car.

The Red Sox third base post remained a veritable turnstile in 1948; in the April 15 season opener Pellagrini earned the first crack. His third-inning home run off future Hall of Famer Early Wynn – the American League’s first homer of the season – provided a 2-0 cushion in a 7-6 win against the Senators. The dinger was an immediate reward for Pellagrini’s diligent spring training efforts to add some power to his stroke. Unfortunately it would have the opposite effect. Though Pellagrini had some pop, swinging for the fences hampered his natural swing and he stumbled into a 1-for-23 hole. In an attempt to keep Pellagrini’s glove on the field, Cronin switched him and Pesky. “Pellagrini … could play shortstop on any team in the American League,” the skipper said. “[A]s far as his hitting, he looks good at the plate. He has a good stance, a good stroke, and he looks better up there than a lot of my players. I’ve just got to wait and see whether he can deliver.”5

The move produced near-immediate dividends as Pellagrini responded with a .293-2-10 line through May 17. The surge quickly yielded to a 1-for-22 skid that brought an end to the Pesky-Pelly switch. After spending nearly a month riding the bench, Pellagrini was returned to the third base platoon. He finished with an uninspiring .202-1-6 in his final 114 at-bats. On November 17 Pellagrini was traded to the St. Louis Browns with five others for two All-Star performers: pitcher Jack Kramer and shortstop Vern Stephens. The trade was perceived as a salary cutting measure by the Browns, an argument seemingly bolstered because only one of the players stayed with St. Louis for more than two full seasons. But seeing an opportunity to move beyond part-time play, Pellagrini was elated: “I can just see the Boston streamer headline next season: ‘Strengthened Browns return to Fenway Park led by Eddie Pellagrini.’”6

A promising 1948 spring camp gave way to a dreadful start as Pellagrini finished the first month of the season with a dismal .095 average. He found his footing in May, only to be sidelined 19 games with a pulled leg muscle. Pellagrini’s defense afforded continued play as he placed among the league leaders in double plays turned and was the only AL shortstop to participate in two triple plays during the season. A minor .263 surge over the final two months earned Pellagrini career-highs in appearances (105), at-bats (290), hits (69), walks (34), and total bases (89).

Injuries marred much of Pellagrini’s next season as he was limited to just 79 appearances. On June 4, 1949 he dislocated his left shoulder diving for a groundball that made its way to centerfield. A month later he sustained a split lip and broken tooth after being hit in the face by a thrown ball. Inexplicably Pellagrini’s signature defense failed him. Three errors in six games prompted manager Zack Taylor to acknowledge “Pellagrini has been having a rough time at short … I called Eddie in … and told him I was benching him in the hope that the rest would do him good.”7 8 Pelly finished with a disappointing .238-2-15 line in 235 at-bats. In the wake of the Browsn’ 101-loss season, the front office announced that he was one of 14 players age 28 or older who were on the block as the club steered toward a five-year youth movement. In November rumors surfaced of Pellagrini’s inclusion in trade packages to the Philadelphia Athletics and New York Yankees, but nothing came of these. Two years removed from pension eligibility, he was stunned (and threatened to quit) when he discovered he was sold to the Baltimore Orioles of the International League on November 25. “I’m not washed up and I don’t feel that I’m ready to be sent to the minors,” Pellagrini stated. “I can still field, run and throw. Maybe I won’t hit .300 but how many shortstops do … I could help [many clubs] – even as a utility player.”9

For the second of three consecutive years Pellagrini joined a barnstorming squad playing against semi-pro clubs in New England and Canada (years later he was joined by Pesky). In December he traveled south to play in the Cuban Winter League for the first time in hopes of attracting major league attention, but none came. Pelly was still uncertain about his future, but it appears that Jack Dunn, the Orioles’ owner-president, convinced him to give baseball another try. The advice proved providential when Pellagrini raced to a .321-8-34 line in his first 61 games of the 1950 season. Dubbed a second Eddie Joost – who had resurrected his career four years earlier in the International League – Pellagrini began receiving attention as an early MVP candidate. An injury to his right hand from a pitched ball slowed him in the second half, but he finished among the team leaders in most offensive categories (including a surprising 19 home runs). In September the Philadelphia Phillies inquired as to Pellagrini’s availability to help in their pennant drive, but the Orioles would not budge. They looked to him to lead them in the Junior World Series, where they eventually fell to the Columbus Redbirds in five games. A move to the National League champion Phillies took place after the season.

In 1951 rumors surfaced that Pellagrini might win the second base starting job from Mike Goliat, though manager Eddie Sawyer’s thoughts never strayed beyond a utility role for the newly-acquired infielder: “[Pelly] is a fine player, an excellent fielder. He’ll make a good relief for [Granny] Hamner or [Willie] Jones.”10 But when Goliat started slow – two hits in his first 14 at-bats – Pellagrini was inserted in the lineup. Beginning May 20 he spelled Jones for five games at third when the latter suffered an injury to his right foot. Ever the fierce competitor, on May 26 Pellagrini surprisingly avoided a fine and suspension after pushing first base umpire Frank Dascoli during a disputed eighth inning call (Pelly was ejected). After wrestling the second base job away from all comers beginning July 4 – the Phillies used seven players there – Pellagrini was sidelined by a severe thumb injury that relegated him to pinch-hitting and pinch-running through most of August.

When the season ended, Pellagrini’s name surfaced in a rumored trade with fellow Massachusetts native Eddie Waitkus to the Boston Braves for first baseman Earl Torgeson. After the Braves quashed the story, Pellagrini was traded to the Cincinnati Reds as part of a seven-player swap. Used sparingly in Cincinnati, Pellagrini received just four at-bats through the first 34 games of the 1952 season. On May 27, after injuries decimated the Reds’ roster, he made his major league debut at first base and connected for a game-winning homer in the 14th inning. But infrequent use caused his average to dip below .200; he finished with a .170-1-3 line in 100 at-bats.

Resigned to strictly a utility role, Pellagrini was one of the first players to sign with the Reds the following year. On March 26, 1953, six weeks removed from becoming a 10-year pension eligible player, he was released to the Baltimore Orioles. “I felt that I was fielding sharply and hitting well, and that I was in peak physical condition,”11 Pellagrini said. He returned to his Weymouth, Massachusetts home, vowing once again to quit. On the verge of landing a lucrative position with a sales promotion firm, Pellagrini was elated when he received word that the deal to Baltimore was canceled and he was sold to the Pittsburgh Pirates. On April 26, on the first pitch he saw that season, he connected for a two-run pinch-hit homer off future Hall of Famer Robin Roberts. Six weeks later Pellagrini knocked a game-winning three-run pinch-hit homer off St. Louis Cardinals’ lefty Harvey Haddix (the blast came two days after Pelly celebrated the 10-year threshold). The US Army’s induction of the Pirates’ middle infield twin brother combo of Johnny and Eddie O’Brien in September afforded Pellagrini more play. He responded with six consecutive hits on September 7 to lead the Pirates to a doubleheader sweep of the New York Giants. Five days later his 12th-inning single drove in the winning run in an 8-7 contest against the Cardinals.

Baseball players are a superstitious lot and the number 13 is generally shunned, but not by Pellagrini. On February 13 he signed a contract to play with the 1954 Pirates. “I always sign on the 13th,” he explained. “I was born on the 13th of March and … most of my lucky days are on the 13th of any month. And I wear the No. 13 on my uniform.”12 13 In fact the number had even greater significance. In 1945 Pellagrini received his release from the US Navy on the 13th of October. In 1954 he agreed to begin taping a 15-minute radio show for WJDA in Quincy, Massachusetts, a station located at 1300 on the dial. The first airing: March 13. When his Pirates teammates got wind of Pellagrini’s strange obsession, they hid his number 13 uniform before a March 25 exhibition against the Athletics. The surehanded fielder took to the field with a different number and committed two errors.

But this was not the end of the pranks. In 1954 southpaw Joe Page signed with Pittsburgh in a short-lived comeback attempt, rooming with Pellagrini and pitcher Max Surkont at the Pirates’ new spring training facility in Fort Pierce, Florida. When manager Fred Haney learned of the roommates’ challenges with Page’s loud snoring, he could not resist needling the pair: “Page has an unusual quirk in that he’s a sleepwalker who likes to imagine he’s a barber. He takes a straight razor and will frequently shave a sleeping roomie without bothering to lather him up. So you boys better hope that Page keeps snoring.”14

Pellagrini made 73 appearances with the Bucs during the 1954 season; more than half (41) as a pinch-hitter or pinch-runner. In April the Senators expressed interest in the infielder but nothing came of this. On August 8 Pellagrini collected four hits and five RBIs in leading the Pirates to a doubleheader sweep of the Cardinals. But this proved to be one of his last hurrahs. He managed just four hits in his final 31 at-bats to finish with a .216-0-16 line. On October 12 he was given his release. He returned to Massachusetts to his wife and four children.

In 1942 or 1943, Pellagrini married Chicago native Helen Rita Sheridan.15 Four years his junior, Helen was the fourth of four daughters of Edward and Anna Sheridan. The union eventually produced five children, including twins born on August 23, 1947. Helen passed away in Braintree, Massachusetts in May 1976, one month before her 54th birthday. Pellagrini never remarried.

In 1955 Pellagrini entered a real estate venture called Twin Shores Realty Company alongside some prominent Red Sox alumni: Pesky, Dom DiMaggio, Walt Dropo, and Sam Mele. He was loved and respected as “Mr. Class,” a label he earned in Baltimore in 1950, with the possible exception of one family in the Boston area. (Three years earlier Pellagrini had been charged with assault in a dispute with his landlady and her sons. After paying an initial fine his case was dismissed in January 1948 when the jury could not reach a verdict.) The Bostonian, his high school yearbook, noted his “cheery countenance” from an early stage, an outlook that never waned throughout his life. Bill Flynn, Boston College’s athletic director, determined that these characteristics made Pellagrini the ideal person to shepherd the young men on the Eagles’ baseball team. In 1958 he was hired as the Eagles’ baseball coach.

Nationally known as a football powerhouse, Boston College had made much less headway in baseball. This quickly changed under Pellagrini’s guidance. In 1960 and 1961 he led the Eagles to the College World Series, a feat he repeated in 1967. Four additional NCAA District I playoff appearances were added to a 30-season résumé ending in 1988 (he missed the 1969 season because of illness). Pellagrini compiled 359 wins, a school record, while never keeping statistics on individual players. “All my players are of equal importance to me,” he said proudly. “The young man who only plays one inning, but still has the incentive to come out every day, impresses me. It is this character I like to build upon, for a winner is not developed on the baseball diamond, but in the mind … No person likes to win as much as I do, but education is the primary concern.”16

In 1968 Pellagrini was appointed to the board of directors of The Bosox Club, an organization of businesses and fans supporting the Red Sox. Two years later he was inducted into the inaugural class of the Boston College Varsity Club Athletic Hall of Fame. Maintaining a regular presence on the rubber-chicken circuit, Pellagrini was one of many ex-Red Sox players in attendance in 1963 when the Boston sports writers paid tribute to Pesky. On January 25, 1972 Pellagrini was honored by the same writers’ association. Twenty-two years later he was ushered into the American Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame (the only Boston College representative to receive this honor through 2015). On May 3, 1997 the college’s baseball field was rededicated as Eddie Pellagrini Diamond at John Shea Field.17 The plaque at the entrance to the baseball field reads:

A Teacher, Coach, Folklorist and Friend

To Anyone Who Shared His Undying Love for the Sport of Baseball

Eddie Pellagrini Is A “Major Leaguer” In Every Sense of the Term.

In 2000 the Edward C. Pellagrini Scholarship Fund was established to benefit Boston College athletics. Six years later Pelly attended the Fenway Park Opening Day commemoration honoring 60-year anniversary of the Red Sox 1946 World Series squad.

Pellagrini passed away in Weymouth on October 11, 2006, five months removed from his 89th birthday. Survived by three of his five children, he was buried in Massachusetts National Cemetery in Bourne, 50 miles southeast of Weymouth. The family requested donations to the Boston College Diamond Club (care of the Boston College Athletic Association) in lieu of flowers.

In 1954 Pellagrini concluded an eight-year major league career with an uninspiring .226-20-133 batting line in 1,423 at-bats. But Pelly’s contributions were much more. He worked with youngsters at all levels and, following his playing days, was an inspiration to young people on the Boston College campus. Perhaps no one summarized Pellagrini’s life better than fellow Italian-American Tommy Lasorda: “[Pellagrini] was a consummate teacher and a friend to all.”18

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Rod Nelson, Chair of the SABR Scouts Committee, David Vincent, and Bill Mortell for their valuable input. Thanks also to Ann Pellagrini, daughter of Eddie Pellagrini, for providing several corrections (received via e-mail, October 21, 2018).

Sources

Websites

Ancestry.com

miscbaseball.wordpress.com/tag/eddie-pellagrini/

graphics.fansonly.com/photos/schools/bc/sports/m-footbl/04-media-guide/04university.pdf

bc.edu/bc_org/rvp/pubaf/06/pellagrini.html

bceagles.com/facilities/?id=10

bceagles.com/hof.aspx

newspapers.bc.edu/cgi-bin/bostonsh?a=d&d=bcheights19800201.2.53

tommy.mlblogs.com/2012/01/19/the-great-eddie-pellagrini/

Notes

1 “Yaz Sure He Can Produce Five More Banner Years,” The Sporting News, December 23, 1972: 39.

2 “Red Sox Memories,” Misc. Baseball: Gathering Assorted Items of Baseball History and Trivia (April 19, 2009). (https://miscbaseball.wordpress.com/tag/eddie-pellagrini/ ).

3 Always proud of his heritage, Pellagrini was honored by his selection to the 1954 outstanding American-Italian major league club by Unico National, the Italian American service organization.

4 “Red Sox Memories.”

5 “Hits to Decide Hot Fight at Red Sox’ Hot Corner,” The Sporting News, March 26, 1947: 7.

6 “From the Ruhl Book by Oscar Ruhl,” ibid., December 10, 1947: 22.

7 “Browns Crack Back at Al – and Charge of Defeatism,” ibid., May 18, 1949: 20.

8 “Taylor Looks to Bullpen to Correct Hill Problem,” ibid., June 8, 1949: 19.

9 “Pellagrini Balking at Trip to Minors, May Quit Game,” ibid., December 7, 1949: 35.

10 “Experts Third-Place Forecasts Help Sawyer to Pep Up Phils,” ibid., February 28, 1951: 8.

11 “Vet Ed Pellagrini as Excited as Rookie over Buc Chance,” ibid., April 29, 1953: 37.

12 “Pellagrini Delays Signing Until 13th, His Lucky Day,” ibid., February 24, 1954: 31.

13 Pellagrini’s claim of signing on the 13th of the month every year was a slight exaggeration; when he was released following the 1954 season his uniform number was inherited by future Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente.

14 “From the Ruhl Book,” May 5, 1954: 14.

15 Pellagrini claimed he met his wife on the 13th (year unknown) and dated for 13 months before they were married.

16 “Baseball: The Pellagrini Era,” Boston College – The Heights, Number 21 (February 1, 1980). (http://newspapers.bc.edu/cgi-bin/bostonsh?a=d&d=bcheights19800201.2.53 ).

17 US Navy Commander John Joseph Shea played football at Boston College from 1916-1917. He died on September 15, 1942 during the Battle of Guadalcanal, Pacific Theatre.

18 “The Great Eddie Pellagrini,” Tommy Lasorda’s World (January 19, 2012). (http://tommy.mlblogs.com/2012/01/19/the-great-eddie-pellagrini/ ).

Full Name

Edward Charles Pellagrini

Born

March 13, 1918 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

October 11, 2006 at Weymouth, MA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.