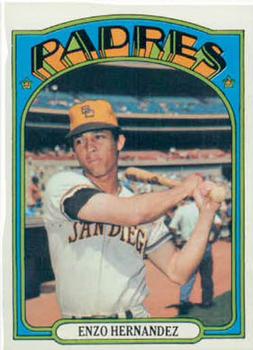

Enzo Hernández

In his time, Enzo Hernández was a special player for fans of Venezuelan baseball. Both Hernández and David Concepción were thought of as successors to Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio, and Venezuela began to be seen as the cradle of the shortstop.

In his time, Enzo Hernández was a special player for fans of Venezuelan baseball. Both Hernández and David Concepción were thought of as successors to Alfonso “Chico” Carrasquel and Luis Aparicio, and Venezuela began to be seen as the cradle of the shortstop.

Enzo Octavio Hernández Martínez was born on February 12, 1949, in the hamlet of El Guasimo, near Valle Guanape, Anzoategui State, on the farm of his grandfather Pedro Rafael Valera, the popular “Don Rubito.” His parents were Ricarte Hernández and Ramona Martínez de Hernández, who lived in a nearby town, San Tomé. When Enzo was barely a year old, his father was a nurse employed in the hospital of the Mene Grande Oil Company. Enzo began high school at the Liceo Briceño Méndez, and then attended Liceo Guanipa, but he left school after signing at age 17 with Los Tiburones de La Guaira in Venezuela and the Houston Astros.1 La Guaira is a coastal city about 30 km (18.6 miles) from Caracas. The team typically plays its home games in Caracas.

Hernández had only played baseball as a street game before 1959, when Francisco Pinto, an important former Venezuelan amateur player, organized a children’s championship that gave 10-year-old Enzo the opportunity to start playing organized baseball. He played in the 1959 national championship, in Maturin, Monagas state. Two years later, he was selected to represent Anzoátegui state in the national championships. There was no organized baseball for young adolescents, but at age 16, he joined the AA team of the Mene Grande Oil Company. His play earned him a position with the highest-level amateur team in the 1965 national games in Barcelona, capital of Anzoátegui. Alfonso Carrasquel selected him for the team. Enzo told author Carlos Cárdenas Lares, “Before I got to training, I was told that Alfonso was interested in me. I had gone as a second baseman, but I did not like the position very much because I had never played it. Later, I told Alfonso that I did not really play that position, but shortstop since I was 9 years old, so he put me in the shortstop and, although many people criticized him, Anzoátegui’s shortstop in those nationals was me.”2

In 1966 Hernández continued playing top-level amateur baseball and after he appeared at the national games, he was signed by Tiburones de La Guaira. As he told Cárdenas Lares, “The people of La Guaira had seen me in Maracay and they went to look for me in Puerto La Cruz, where I had moved with my family. They took me to Catia La Mar, to the Mamo military base. There I was practicing the team and they signed me for 3,000 or 5,000 bolivars.”3

Five thousand bolivars was equivalent to $1,162 US at the time. Hernández was signed at the same time by Tony Pacheco, a scout for the Houston Astros. In his first year in the United States, he was sent to the Cocoa Astros of the Class-A Florida State League. He appeared in 129 games and it was a difficult year: He batted only .187 and made 39 errors. It was a tense time and he worried that he would be released.

He added, “With only a little to finish the season, the manager [Walt Matthews] called me. I was scared … but it was to send me to Houston for a few days to see the big-league games, while the Instructional League began. It was positive for me. As Tony Pacheco told me, if after having hit .180 in Class A they did that, it was because they saw something special in you.”4

Starting at age 18 with the Tiburones de La Guaira in the 1967-1968 season, his luck could not be better — the team’s player-manager was Luis Aparicio. Aparicio already had 12 major-league seasons as a shortstop with the Chicago White Sox and Baltimore Orioles, had been Rookie of the Year in 1956, had seven Gold Gloves and nine consecutive seasons leading the American League in stolen bases. Aparicio was looking for a shortstop who would allow him to take a breather. Enzo played in 32 of the team’s 60 games, finishing with a .235 batting average. Aparicio was in 40 games at either shortstop or third base.5

In 1968 the Astros assigned Hernández to the Greensboro Patriots of the Class-A Carolina League, where he played in 89 games, batting .226 with 38 errors. He got into three Triple-A games for Oklahoma City of the Pacific Coast League. He still needed work to improve his game.

In Venezuelan League winter ball, the Tiburones made Hernández the regular shortstop in 1968-69. Aparicio appeared in only 15 games and was no longer manager. Hernández was largely on his own. Although he batted just .228, he was more solid defensively, playing alongside experienced quality players such as Remigio Hermoso at second base and José Herrera at third. The Tiburones won their fourth Venezuelan Professional Baseball title in the team’s first seven years. It was Enzo’s first great professional triumph.

In December 1968, while playing in Venezuela, he was traded by the Astros. He was sent to Baltimore along with Cuban pitcher Miguel Angel “Mike” Cuellar and a minor-league player for Curt Blefary and another minor leaguer. In 1969, Cuellar became the first Latin American player to win the Cy Young Award as the best pitcher in the American League (shared with Denny McLain). The Orioles wanted Hernández as a backup to their shortstop, Mark Belanger, coming off his first full season as starter.

The Orioles placed Hernández with the Dallas-Fort Worth Spurs of the Double-A Texas League, but he played in just two games before being assigned to the Miami Marlins of the Class-A Florida State League. He became a much more selective hitter with good contact, and had above-average speed and solid defense. He was a difficult hitter to strike out in 1969, with just 17 strikeouts in 425 plate appearances. He stole 26 bases in 30 attempts and hit for a career-high .247.

The Orioles added Hernández to their 40-man roster and invited him to spring training with the big-league club in 1970. His first 42 games were with Dallas-Fort Worth, where he hit .282. Promoted to the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings (International League), he hit .266 in 100 games, with 17 stolen bases, 61 runs scored, 39 RBIs, and only 22 strikeouts (one every 19 plate appearances). In addition, he perfected the bunt as a weapon that gained him 12 successful sacrifices to advance the runners. But Mark Belanger, who had succeeded Aparicio with the Orioles, seemed set at shortstop.

The 1969 expansion added two new teams in each league. One of the expansion teams was the San Diego Padres, managed by Preston Gómez, the first Latin-American named as manager for a full season in the big leagues. He hadn’t been satisfied with the work of the shortstops he’d had and kept his eye on Hernández.

“Hernández could solve our shortstop problem for years to come,” Gómez told The Sporting News.6 In December 1970 the Orioles and Padres executed a six-player trade. Hernández, Fred Beene, Tom Phoebus, and Al Severinsen went to the Padres for Pat Dobson and Tom Dukes.7

That winter, Enzo played his fourth season for the Tiburones de La Guaira, won his second title with the team and went to his first Caribbean Series. The Tigers del Licey won the Series in Puerto Rico in February 1971.

To win the job as starting shortstop for the Padres in 1971, Hernández had to beat out both the Quisqueyano Rafael Robles and Tommy Dean, who had played the most Padres games in their two-year history. He won the job. Dean remained as backup. Gómez had his new shortstop.

Hernández debuted on April 17, 1971, against the St. Louis Cardinals in San Diego. He wore number 11 on his back, a tribute to his idol and mentor Aparicio. Tom Phoebus started for the Padres; future Hall of Famer Steve Carlton for the Cardinals.

Hernández batted eighth. His first big-league at-bat came in the bottom of the second, with the Cardinals up 1-0. He drew a base on balls. In the bottom of the fourth inning, the Cardinals holding a 2-0 lead, he got the first of his 522 major-league hits. Carlton shut out the Padres, 4-0.

In most of his 143 games in 1971, Hernández batted leadoff. He finished his first season with a .222 batting average, 21 stolen bases, 54 walks, 34 strikeouts, and 12 sacrifice hits. He had become the first Latin American shortstop to steal more than 20 bases in the National League. The only other Latin rookie to steal at least 20 bases was his mentor, Luis Aparicio, who had stolen 21 bases in 1956.

In the Venezuelan Professional Baseball League, Hernández played his fifth consecutive season with the Tiburones de La Guaira. He reported late and played in just 24 of the team’s 60 games. It was the first time in three seasons that he finished with fewer than 200 at-bats in Venezuela, but in both 1970 and 1971, he had batted more than 500 times in US baseball. He joined the Tiburones de La Guaira in their eighth consecutive final.

For the 1972 Padres season, Hernández began as the team’s regular shortstop. After a last-place finish in 1971 and a slow start in 1972, ownership replaced Preston Gómez on April 27, 1972, with Don Zimmer. One of the best allies Hernández had in his career left the team. Zimmer had Hernández bat in eighth place more games than not. Zimmer also frequently pinch-hit for him later in games, some 45 times in all. Consequently, he had more than 200 fewer at-bats, He hit for a .195 average, but even with so many fewer plate appearances, he stole 24 bases, bettering his own mark for most bases stolen by a Latin American shortstop in the National League. Hernández also led the league as the most efficient base stealer, succeeding 89 percent of the time. Base stealing was coming back as an offensive weapon; Lou Brock led the league with 63.

That winter, Hernández was reunited with Preston Gómez, who was named as manager of the Tiburones. Enzo had one of his best campaigns in Venezuelan league baseball, but La Guaira’s string of eight consecutive seasons reaching the league finals was snapped.

The 1973 Padres season was a difficult one. Hernández appeared in just 70 games, with 247 at-bats, hitting .223 with 15 steals. He had begun to suffer some injuries. Through June 13, he had hit leadoff in almost every game and was hitting .240 with 15 stolen bases, but problems with back pain took him out of the lineup until July 26. When he came back, he was subpar, getting into only 17 games and hitting .149, Derrel Thomas ended up playing shortstop in most of the games when Enzo was out.

Hernández played in Venezuela again in the winter, under Preston Gómez as manager. He demonstrated he had returned to health and finished with the best batting average of his career (.285 with 14 steals). His team finished first in the regular round, and were regarded as favorites for the semifinals, but a player strike brought about a premature end to a season that had looked very promising. Hernández came back to the United States, strengthened and facing a new manager: John McNamara.

The 1974 season was perhaps the best of Enzo’s career as a big leaguer. He achieved personal bests in hits (119), runs batted in (34), runs scored (55), and stolen bases (37).8 He was named Player of the Week in the National League for the week of August 4-11, the first Latin player to earn the honor.

From their inception through 1974, the Padres had always finished last in the West Division, but the farm system began to bear fruit. Dave Winfield had come up and Randy Jones became the first Padres pitcher to win 20 games. Veteran players like Willie McCovey, Bobby Tolan, and Tito Fuentes played well, and the team finished 71-91, in fourth place.

Hernández hit .218 in 116 games, again often pinch-hit for later in games. Nevertheless, he stole another 20 bases and led all of baseball with 24 sacrifice hits. He was the first Latino player in the National League with at least 20 steals and 20 sacrifice hits in the same season.9

In Venezuelan ball, Hernández played for a different team. From 1962 until at least 2019, Caracas had two teams play at the stadium of the Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas, the Leones del Caracas and the Tiburones de La Guaira, both sharing a stadium. The university and teams could not come to agreement on the amount of rent in 1975-76. Consequently, the teams merged and played in another city, Portuguesa, as the Tibuleones. Enzo played in 64 games with 240 at-bats, 18 runs scored, and 17 RBIs. His batting average was the lowest of his career in Venezuela, .213.

The Padres told Hernández in spring training that he’d have to compete to win the shortstop slot; he needed to hit better, and thus put himself in a better position to be able to use his base stealing skills. Hector Torres played a few more games than Hernández in their first couple of months, but Torres hit only .143 during June. Randy Jones also was said to have told manager Dick Williams that he wanted Enzo at shortstop when he was on the mound. As noted, Jones was a 20-game winner. In 1976 he won 22 games and the first Cy Young Award for the franchise.

Despite some back pains in mid-September, Hernández played in 113 games, and hit for a career-best .256 batting average.

His back problems kept him out of Venezuelan ball, save for six games. He spent most of 1977 on the disabled list. Without San Diego’s approval, he underwent back surgery. Though the operation was successful, he was released after only seven games.

Hernández rested during the 1977-1978 season in Venezuela. In April 1978 the Los Angeles Dodgers signed him to a minor-league contract, and he was sent to the Triple-A Albuquerque Dukes. He was called up to the Dodgers in mid-August and appeared briefly in four games, with only three plate appearances. There were his last games as a big leaguer.

Hernández had played over eight seasons, with 2,612 plate appearances, 522 hits, 129 stolen bases, and 83 sacrifice hits. He was successful in 79.6 percent of his stolen-base attempts (129 steals in 162 attempts).

With the Tiburones Hernández played his 11th season and seemed to have fully recovered from his injuries. He played in 62 games and batted .251 in 231 at-bats. For the first time in its history, La Guaira failed to reach the semifinals, finishing last in the regular round.

At this point, Hernández simply disappeared from public sight; there were no announcements of his retirement. Since he was only 29 years old, many expected his return, but new players came along and Hernández remained out of the public eye.

Enzo continued his life in the city of El Tigre in eastern Venezuela with his wife (since 1972), Ellys, and their two daughters, Ellys Maria and Janet Virginia. The Hernández family dedicated themselves to running a pharmacy that they had in partnership with Dr. Antonio Caraballo, Enzo’s father-in-law.

On January 13, 2013, Enzo Hernández took his life at his home. He had been suffering acute depression and a reported decline in health. Bruce Markusen in an article in Fangraphs noted a number of recent suicides among former baseball players. He wrote, “Hernández’ passing did not create major headlines, but it has stirred a reaction from me on two different fronts. The first involves a broader issue, one that seems to be becoming more prevalent in our society. If the preliminary reports of suicide are true, Hernández becomes the fourth former big leaguer to take his own life in the last two years, after Mike Flanagan, Hideki Irabu, and Ryan Freel. If we go back a little further, former major league infielder Keith Drumright committed suicide in 2010, and retired pitcher Brian Powell took his own life in 2009. So that is six suicide deaths in the past four years.”10

The cause of death was an apparent overdose of prescribed painkillers.11

Markusen added, “[T]hese suicide deaths should not be completely ignored. The Alumni Association and the Baseball Assistance Team do terrific work with ex-players during their retirement years, but that is not always soon enough for some players. Perhaps Major League Baseball (or the Players’ Association) should look further into the ways that players are prepared for their post-playing careers. Do players receive counseling, during their careers, about how to make the eventual move from ballplayer to real life? Are most major leaguers ready for the next part of their lives once their careers have ended? What are the financial difficulties faced by players, especially those who played a good portion of their careers before free agency and never made big money?”12

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com and www.pelotabinaria.com.ve. Most of the Venezuelan baseball statistics mentioned in the work were taken from the latter source.

Notes

1 http://destellosdelamemoria.blogspot.com. Personajes de mi pueblo: Enzo Hernández. Por José “Cheo” Salazar.

2 Carlos Cárdenas Lares, Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas, sus Vidas y Hazañas, Segunda edición (Caracas: Fondo editorial Cardenas Lares, 1994), 126-130.

3 Cárdenas Lares.

4 Cárdenas Lares.

5 Daniel Gutiérrez, Efraím Álvarez, y Daniel Gutiérrez G., La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela (Caracas: Liga Venezolana de Beisbol Profesional, 2006), 149-209.

6. Bruce Markusen, “Cooperstown Confidential: Farewell to Enzo Hernández, Fred Talbot and Sports Watch,” fangraphs.com, January 18, 2013. https://tht.fangraphs.com/cooperstown-confidential-farewell-to-enzo-hernandez-fred-talbot-and-sportsw/.

7 Markusen.

8 In 1974 Dave Concepción set the new record for stolen bases by a Latin American shortstop, with 41.

9 In the American League, Cuba’s Armando Marsans stole 46 bases for the St. Louis Browns in 1916 and sacrificed 23 times, Luis Aparicio had stolen 51 and sacrificed 20 times in 1960, and in 1972 Bert Campaneris stole 52 bases, sacrificing 20 times.

10 Markusen.

11 George Voutiritsas, “15 Baseball Players You Didn’t Know Took Their Own Life,” The Sportster.com, July 13, 2017. https://www.thesportster.com/baseball/15-baseball-players-you-didnt-know-took-their-own-life/.

12 Markusen.

Full Name

Enzo Octavio Hernandez

Born

February 12, 1949 at Valle de Guanape, Anzoategui (Venezuela)

Died

January 13, 2013 at El Tigre, Anzoategui (Venezuela)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.