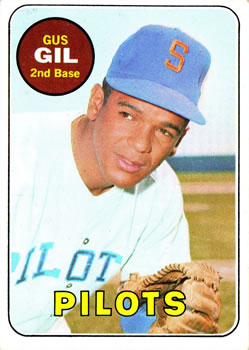

Gus Gil

Prior to Edgardo Alfonzo and José Altuve, three Venezuelan second basemen stood out for their skills: Manny Trillo, Remy Hermoso, and Gustavo “Gus” Gil. Trillo was the most complete player of the trio and Hermoso was likely blessed with the most speed – but Gil was peerless with the glove. He executed split-second double plays and ranged far to his left to capture grounders just before they reached the outfield grass. He would gallop behind the second-base bag to backhand balls, twist in the air, and fire picture-perfect strikes to first base. Gil’s defensive prowess prompted broadcaster Delio Amado León to deem “a ground ball to second… a ground-rule out.”

Prior to Edgardo Alfonzo and José Altuve, three Venezuelan second basemen stood out for their skills: Manny Trillo, Remy Hermoso, and Gustavo “Gus” Gil. Trillo was the most complete player of the trio and Hermoso was likely blessed with the most speed – but Gil was peerless with the glove. He executed split-second double plays and ranged far to his left to capture grounders just before they reached the outfield grass. He would gallop behind the second-base bag to backhand balls, twist in the air, and fire picture-perfect strikes to first base. Gil’s defensive prowess prompted broadcaster Delio Amado León to deem “a ground ball to second… a ground-rule out.”

Gil had a long professional career in his homeland (19 winters from 1959-60 through 1977-78) and in the U.S. (17 summers from 1959 through 1975). He never hit for much power but batted .286 in the high-caliber Venezuelan League. However, Gil played just parts of four years (1967, 1969-1971) in the majors as a utility infielder, “I thought he was a great one,” said Gabe Paul, who originally signed him for the Cincinnati Reds.1 Yet despite his fine glovework, Gil hit only .186 at the top level. Like many men with baseball in their blood, though, Gil went on to serve the game for many years as a coach, manager, and scout.

Tomás Gustavo Gil Guillén was born in Caracas, Venezuela on April 19, 1939. He was the second of Tomás Gil and Angelina Guillén’s six children – the lone boy among five girls: Rosa Lucía, Elsa, Zaida, Argelia, and Iraida. The elder Tomás was a typesetter while Angelina worked as a cook at the Urdaneta national guard station in Catia parish. When Gustavo’s father noticed his son’s great love for baseball, he bought a few bats, nine gloves and some catcher’s gear so the youngster could play with his friends in a sandlot near the Gil’s home. Gustavo was ecstatic at his father’s generosity but lamented the 5 p.m. curfew. Tomás Sr. would interrupt games just as they were getting interesting, collect the equipment, and state that the competition could resume tomorrow.2

Some of Gustavo’s friends included Francisco José “Teodoro” Obregón, who played 17 seasons in the minors, and future big-leaguer César Tovar. “César practically grew up with me,” said Gil. “In fact, he called my mother ‘Mom.’”3 Tovar later named one of his sons Jhonny Gustavo in honor of his friend.4

Gustavo graduated from Luis Razetti High School, where he excelled in baseball, volleyball, and basketball.5 He played with Venezuelan volleyball star Papelón Borges on an amateur league team, representing the federal district of Caracas. After graduation, he joined his father in the print shop.6

Gustavo was superstitious both between and outside of the foul lines. While he always entered the dugout through the clubhouse doors, he preferred to leave the diamond by climbing the fence and exiting through the stands of the Universidad Central de Venezuela (Venezuela Central University) Stadium. After a good game, he would refuse to wash his underwear, preventing anyone from even touching it.7

By then 5-foot-10 and a svelte 145 pounds (he was listed at 180 pounds in the majors), Gil showed off his skills in the amateur, Double-A Venezuelan League on a well-known team sponsored by Cartografía Nacional. His on-field exploits were noticed by former Negro Leaguer Manuel Garcia, a Cuban baseball legend who resided in Venezuela. García’s tutelage helped Gil improve his batting and become even more efficient defensively. Once García deemed the youngster ready for the next step, he contacted Cincinnati scout Reggie Otero, who promptly offered Gil a professional contract with the Reds organization. Since Gil was still a minor, his father signed the agreement on his behalf. However, the deal was not publicly announced, and Gil continued playing amateur baseball, capturing the batting title when Caracas hosted the Central American and Caribbean Games in January 1959.8

Reds GM Gabe Paul also signed Tovar, though only Gil received a bonus ($2,000).9 Paul told the story himself in 1968. “I went to see Gus Gil in a morning workout. He insisted on bringing Tovar along. Gil was the man we wanted. . . He wanted his buddy Tovar signed, too. César showed nothing, but I signed him to get Gil.”10

Fresh off the international competition, Gil made his professional debut with the Geneva (New York) Redlegs of the Class D New York-Pennsylvania League in 1959. With Tovar manning second base, Gil played shortstop in 109 of his 116 appearances and led the NYPL with 62 double plays. Gil also batted .267, walked 90 times for a .396 on-base percentage, and paced the circuit with 104 runs scored. That winter, beginning a pattern that would last nearly two decades, Gil returned home to play in the Venezuelan League. Just 20 years old, he played 29 games for the Industriales (Industrials) of Valencia, often competing against men up to twice his age.

In 1960, Gil was promoted to the Missoula (Montana) Timberjacks of the Class C Pioneer League. Still a shortstop with Tovar at second, Gil improved his batting average to .313 in 119 games, with 61 RBIs and 74 runs scored. He finished the season by going 6-for-32 (.188) in nine Triple-A Pacific Coast League (PCL) contests with the Seattle Rainiers.

That winter, Gil enjoyed his first solid season with the Industriales, hitting .275 in 51 games as the club won the circuit’s championship. Though Gil mostly played third base in that campaign, he began working out at second; partnering with his childhood friend – shortstop Teodoro Obregón – on and off the field, chatting in the dugout and analyzing plays.

Gil returned to shortstop with the Columbia (South Carolina) Reds of the Class A South Atlantic League in 1961. In 127 games, he batted .269 with a .369 on-base percentage but produced only 13 extra-base hits. Back in Venezuela, Obregón convinced Industriales manager Rodolfo Fernández that shifting Gil to second base would tighten up the team’s defense. The club missed the playoffs, but Gil batted .273 while forming the league’s best double-play combination with Obregón.11

When Gil joined the Macon (Georgia) Peaches of the Class A South Atlantic League in 1962, it was the first of four straight minor-league seasons he would play under skipper Dave Bristol, a great believer in defense, the hit-and-run, bunts and stolen bases. Bristol’s insights rubbed off on Gil as a player – and later as a manager – given their mutual intelligence and reflective approach to the game. With Tommy Helms at shortstop and Pete Rose playing second, Gil moved to third base and hit .276 in 134 games to help the Peaches claim the league championship. In Venezuela, Gil batted a career-high .357 with 25 runs scored in 38 contests as the Industriales triumphed as well.

Gil returned to Macon in 1963 and batted .277 in 134 games as Bristol’s Peaches – now reclassified as a Double-A affiliate – finished with the Sally League’s best regular-season record at 81-59. During his first season playing second base regularly in the United States, Gil impressed teammate Daniel Neville, who said, “He saved me many times… with plays I didn’t think could be made. It’s nice to have such a fielding whiz playing behind you.”12 In Venezuela that winter, the Industriales tied for first place under a new manager – Bristol – before falling in the championship series. Although Gil was unable to reach his previous year’s batting zenith, he batted a respectable .279 in 51 games. On mornings and off-days, Gil and Bristol reconditioned a downtrodden sandlot for neighboring schoolchildren.13

In 1964, Gil advanced to the Triple-A PCL and hit .305 with a team-high .390 on-base percentage as Bristol’s San Diego Padres won the West Division and defeated the Arkansas Travelers in the best-of-seven playoffs. “I know some fans think Gil is our most valuable player, even if he hasn’t hit a home run (he hit one all season) and we have slugger Tony Perez,” remarked Padres GM Eddie Leishman that summer.14 Both Gil and his double-play partner, Helms, were named to the all-star team. “Gil doesn’t come up with one great play after another. He executes two great ones after another,” observed Bristol. “He will make some plays that look impossible.”15 Back home, Gil’s Industriales failed to reach the post-season, despite his .345 batting average in 46 games.

Gil’s second season with San Diego was disappointing. The team finished below .500 in 1965 with a 70-78 record, and Gil’s average slipped to. 256. However, he established career highs with 106 double plays and a .980 fielding percentage. Gil was deemed among the best defensive infielders in the Reds organization, with some rating him above Rose and Helms.16 In Venezuela, he rebounded to bat .315 with a league-leading 21 doubles as the Industriales defeated the powerful Caracas team to reach the finals before falling to La Guaira. The country’s baseball writers named Gil the league’s best defensive second baseman.17

The winter campaign also provided an amusing anecdote with pitcher Roberto Muñoz, a converted catcher who had not yet successfully transitioned to the mound. Muñoz was rushing to reach José Bernardo Pérez Stadium when Gil suggested that he relax by inviting him to first eat some arepas, a typical Venezuelan dish made of cornmeal and assorted fillings. Both players were impressed by the quality; these arepas were filled with shredded cheese and served with ripe tomato and avocado on the side. The meal was leisurely and both players barely made it to the stadium before Industriales manager Johnny Lipon, whereupon Muñoz tossed a great game and earned his first win of the season. A new tradition was born: before Muñoz’s scheduled starts, Gil would meet him for pre-game arepas. (However, the pitcher was not above making modifications; after losses, he would return to the same restaurant but switch the filling to stewed beef or chicken.)18

With the Buffalo Bisons of the Triple-A International League in 1966, Gil hit a solid if unremarkable .267 in 140 games. For most of the season, he formed a formidable double-play duo with his friend Obregón, as manager John “Red” Davis moved Steve Boros back to third base to reunite the Industriales teammates up the middle.19 On October 15, the Reds sold Gil to the Cleveland Indians for an estimated $20,000. Lipon, the skipper of Cleveland’s Triple-A affiliate, managed the Industriales again. “[Gil] has everything you like to see in a major league infielder,” said Lipon, who’d been one himself for parts of nine seasons. “He has great hands – he seldom makes an error… he has excellent range… a good arm… he’s one of the better hit-and-run players in the game today… he knows the strike zone and will accept a base on balls.”20 Gil hit .282 in Caribbean competition that winter.

When Cleveland GM Gabe Paul – the man who’d initially signed Gil for the Reds – was asked why the infielder hadn’t yet cracked the majors, he replied, “It’s really quite simple. [Cincinnati] had Pete Rose and Tommy Helms. That’s all.”21 On April 11, 1967, Opening Day at Municipal Stadium in Kansas City, Gil batted sixth for the Indians and started at second base. In his first at-bat, he reached on an error by Athletics’ third baseman Ed Charles and came around to score the first run of the game. Gil singled against righthander Jim Nash his second time up. After walking in the sixth inning, Gil raced from first to home on a double to tie the score, 3-3, but Cleveland wound up losing by a single tally.

Gil started the Indians’ first 19 games but lost his job by batting just .154. In mid-July, he was demoted to the PCL’s Portland Beavers for 42 games until the Indians brought him back in September. In 51 big-league contests, Gil batted .115 (11-for-96). His experience was positive overall, however, because of the friendships he formed with his countryman Víctor Davalillo, and pitchers Luis Tiant, Orlando Peña, George Culver, and Steve Hargan, with whom he had spent winters in Venezuelan competition.22

Fresh off reaching “The Show,” Gil generated a .319 average in what proved to be his final season with the Industriales. On May 30, 1968, in a complicated offseason swap, he was traded to the Navegantes (Navigators) of Magallanes – a franchise that hadn’t won the Venezuelan League title since 1955 – along with Dámaso Blanco in a seven-player deal.23 When Gil heard the news from one of his sisters, he immediately telephoned Blanco. They promised each other that the Navegantes would win a championship within two years, and kept in touch all season, obsessed with proving their doubters wrong.24

Gil had just been traded stateside as well. After appearing in 24 games for Portland to begin 1968, he was dealt the PCL’s Seattle Angels on May 13 for Chuck Cottier and cash. “Gil to complete season with Seattle, then go on roster of Seattle’s 1969 American League expansion club,” reported The Sporting News.25 Overall, in 135 Triple-A contests, Gil batted .246. Before returning to Venezuela, Gil married Phyllis Young on September 4, 1968.26

True to his promise, Gil raised the Navegantes’ level of play. As team captain, he hit .288 and scored 37 runs in 60 contests. Driven by his determination, the club surprised critics by reaching the finals, where he batted .289 in 38 at-bats. The success was not unexpected to Gil and Blanco; it was part of the vision they crafted once they were traded to the team. The duo led by example and convinced their peers to spend time analyzing the game, win or lose, in the dugout. Afterwards, they would bond over food, beer, and some jovial domino or card games. Gil and shortstop Jesús Aristimuño established such a close connection that their double plays bordered on automatic. It was common to see one flipping the ball in the direction of second base even if the other had not yet reached the keystone.27

As Gil prepared to turn 30, he had nearly 1,800 games of experience in his first decade as a professional across the minors and winter leagues, but his 1967 foray with Cleveland remained a disappointing memory.

In 1969, however, he returned to the majors with the expansion Seattle Pilots. Gil spent the entire season with the American League club, appearing in 92 games – including 44 starts at third base, second or shortstop. Although he batted just .222 in 221 at-bats, he produced a solid .278 (10-for-36) mark as a pinch-hitter. He also received passing mentions in Jim Bouton’s classic diary about that season, Ball Four.

With Venezuela always in mind, Gil recommended Pilots pitcher Dick Baney to the Navegantes front office, and the righthander enjoyed a successful winter ball campaign in 1969-1970.28 That was the year that Gil and Blanco’s prophesy was fulfilled. Although Gil’s .249 average in 57 games was mediocre, he was named the best defensive second baseman in the league.29 He hit .333 in the semifinals, including a game-winning triple in the 14 th inning of Game Three. In the fifth game, Gil robbed Charles “Boots” Day of a likely hit in shallow right field to key another Navegantes victory. The team went on to win the league title.

Then, when the champions of the Puerto Rican and Dominican Leagues came to Caracas for the revival of the Caribbean Series, Gil was named the tournament’s all-star second baseman for delivering 12 hits and seven RBIs in eight games to lead all players. Venezuela prevailed, with Gil driving in the winning run in the decisive game.30

As Venezuelans celebrated, few of the faithful knew of Gil’s internal turmoil. His wife had gone into labor, but the couple was unable to find a hospital in Valencia that would admit them. A clinic finally agreed to care for his wife as soon as possible, but Gil argued with the receptionist after another 20 minutes passed by without any activity. Finally, Gil’s wife delivered twin boys, but the first was stillborn and the second lived for only a few hours. “I could not find the words to tell my wife,” Gil told the author in a 2003 telephone interview. “It was the type of pain that stems from avoidable situations, so it hurts a hundred thousand times as badly. I played in that Caribbean Series with my children in my heart, even though I was focused on the game. I was happy for all the team had accomplished, as we won the title, but the pain of their loss was ever present. That’s why after the last game I grabbed my gear and went home.”31 (On March 12, 1971, the couple welcomed Tomás Gustavo Jr., who passed away in 2020 from coronavirus complications.32)

The Pilots relocated to become the Milwaukee Brewers in 1970, but Gil was returned to the Portland Beavers to begin the year with the franchise’s PCL affiliate. After batting .290 in 30 games, he earned a promotion to the majors, where his old supporter – Bristol – was Milwaukee’s manager. Gil remained with the Brewers for the rest of the season and started 37 of his 64 appearances. He batted just .185 in 119 at-bats, however, including his lone big-league homer, a solo shot off White Sox southpaw Jim Magnuson at Comiskey Park on August 5.

Seeking to secure his spot with the Brewers, Gil returned to Magallanes and enjoyed a fine season. His .271 average in 54 games improved to .300 in the semifinals, including a home run and a triple. The Navegantes reached the finals but lost to the Tiburones (Sharks) of La Guaira in a thrilling seven-game classic despite Gil’s 9-for-29 contribution at the plate. He began the 1971 season with the Evansville (Indiana) Triplets of the Triple-A American Association but earned another call-up by the Brewers in June. In what proved to be his final 14 games in the majors, Gil batted .156 (5-for-32) before he twisted his left knee working out on June 29 and wound up on the disabled list.33

After being limited to 45 appearances between the majors and minors in 1971, the proud infielder washed the bad taste out of his mouth by playing a career-high 61 Venezuelan League games that winter. He was named the best defensive second baseman for the fifth time and hit .313.34 The Houston Astros acquired Gil and assigned him to their Oklahoma City 89ers affiliate in the American Association for 1972, where he hit .238 in 125 games. That winter, he batted .280 for the Navegantes. When Caracas hosted the Caribbean Series in February 1973, the Dominican Republic prevailed but Gil joined Venezuela’s championship Leones club and earned a spot on the tournament all-star team.

The 89ers moved to Denver, where Gil spent the 1973 and 1974 seasons with the Bears, batting .296 in 190 total contests. In between he hit .296 for the Navegantes and led all second basemen with 25 double plays in 60 games.35 In the winter of 1974-75, however, Gil moved to first base. After a .302 performance in 52 regular-season contests, he hit only .143 against Caracas in the seven-game semifinals but went 7-for-16 (.438) with three steals in the finals, but the Navegantes fell to the Tigres (Tigers) of Aragua in six games.

In 1975, Gil returned to the PCL and finished his U.S. playing career by hitting .285 between the Dodgers’ Albuquerque Dukes (23 games) and Padres’ Hawaii Islanders (77 games) affiliates. That winter, he slipped to a meager .233 batting average in 25 games for the Navegantes, his fewest appearances on his native soil. When management told him that the club would move in a different, younger direction the following season, Gil requested a chance to retire on the heels of a respectable season, not a poor one like he had just experienced. His heartfelt request – during which he choked on his words, overcome with emotion – ended with poignant silence. Perhaps resigned to not going out on his terms, the proud ballplayer left the club office, but he was relieved the next day when the franchise called, offering a contract for another season. Gil began to train in earnest for his final performance.36 In 1976, though, a brief appearance with the Poza Rica Petroleros (Oilers) of the Triple-A Mexican League was humbling. He managed just one hit in 30 at-bats.

Yet true to his word, Gil bounced back with a productive 1976-77 season for the Navegantes, batting .265 in 41 games. More importantly, the team won another title, but Gil’s 2-for-32 postseason performance prompted the organization to cut ties. Unwilling to end on such a sour individual note, he signed with the Lara Cardenales (Cardinals) for 1977-1978. After struggling with a .200 average in 24 contests, Gil officially retired at the end of the season, capping a remarkable 19-year Venezuelan League career with a .286 batting average. As of 2021, his 982 hits remain the 10 th-highest total in circuit history.

Although Gil’s career major-league totals were modest (a .186 average in 221 games scattered across four seasons), he was in demand during his retirement. With infield dirt firmly entrenched under his fingernails, Gil could not stay away from the diamond for long. The New York Yankees hired him as a minor-league coach and instructor in 1977 and 1978. In 1979, he was the initial manager for the Maracaibo Petroleros de Zulia in the ill-fated Inter-American League, which failed to complete its inaugural season. Gil became a scout for the California Angels in 1981 and managed the Danville (Illinois) Suns – that organization’s Class A Midwest League affiliate for most of the 1982 season.

In Venezuela, Gil became the Lara Cardenales radio announcer. Ahead of the 1980-81 season, however, another franchise – the Águilas (Eagles) of Zulia, swooped in and named him its skipper. He led them to a 35-25 record and a semi-finals appearance.37 Ultimately, though, Gil’s ties to Magallanes proved to be too deep. Midway through the 1981-82 campaign, he took over for Navegantes manager Jim Williams, but he could not lead the team to the playoffs.38 Gil managed the Tiburones (Sharks) of La Guaira in 1984-85 until he resigned following a midseason loss that was decided by the league office because of an error on the lineup card he had provided to the umpiring crew.39

From 1987 to 1989, Gil was the hitting coach for the Prince William (Virginia) Yankees, in the advanced Single-A Carolina League. His last four years in professional baseball were spent in the Baltimore Orioles system, first as the manager for the rookie-level Appalachian League farm team in Bluefield, West Virginia in 1990-1991, followed by two seasons coaching in the Gulf Coast League.40

After leaving baseball, Gil worked for the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in Alexandria, Virginia.41

Gil was enshrined in the Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame in 2008, alongside Luis Peñaver, Luis Leal, Héctor Benítez Redondo, Gonzalo Márquez, Óscar Prieto Ortíz, and Gualberto Acosta.42 Further accolades followed in 2012 as he was chosen as part of the inaugural class of Magallanes immortals.

Gustavo Gil passed away on December 8, 2015, in Phoenix, Arizona, from respiratory failure. He was 76. Venezuelan newspapers lauded him as “the maestro” and the “legend” for his defensive skills.43 Details of his interment are unknown.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to the late Gustavo Gil (telephone interview with Alfonso Tusa, November 2003).

This biography was translated by Tony S. Oliver, reviewed by Malcolm Allen and Rory Costello, and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to retrosheet.org, baseball-reference.com, retrosheet.org, statscrew.com, and pelotabinaria.com.ve, the author consulted the following sources:

Diario El Nacional (Caracas, Venezuela).

Diario El Universal (Caracas, Venezuela).

Diario Meridiano (Caracas, Venezuela).

Revista Sport Gráfico (Venezuela)

Notes

1 Si Burick, “Blind Man’s Buff,” Baseball Digest, July 1968, 74. Originally published in the Dayton Daily News.

2 Gustavo Maza, nephew of Gustavo Gil, telephone interview with Alfonso Tusa, September 2021 (Hereafter, Maza-Tusa interview)

3 Russell Schneider, “Gil Filling Bill as Keystoner for Indians,” The Sporting News, March 25, 1967: 30.

4 Max Nichols, “Sandlot Pals Gil and Tovar Meet Again – in Majors,” The Sporting News, May 6, 1967: 11.

5 Gustavo Gil, Publicity Questionnaire for William J. Weiss, April 30, 1960.

6 Maza-Tusa interview,

7 Maza-Tusa interview.

8 Carlos Cárdenas Lares, Venezolanos en las Grandes Ligas, (Caracas:Fondo Editorial Cárdenas Lares, 1994).

9 Nichols, “Sandlot Pals Gil and Tovar Meet Again – in Majors.”

10 Burick, “Blind Man’s Buff.”

11 Gustavo Gil, telephone interview with Alfonso Tusa, November 2003. (Hereafter, Gil-Tusa interview).

12 Earl Keller, “Gil No Fish Story – He Makes Big Plays with So Little Effort,” The Sporting News, August 8, 1964:33.

13 Gil-Tusa interview.

14 Keller, “Gil No Fish Story – He Makes Big Plays with So Little Effort.”

15 Keller, “Gil No Fish Story – He Makes Big Plays with So Little Effort.”

16 Felipe Tusa, older brother of author, in-person interview with Alfonso Tusa, March 2012. (Hereafter, Tusa-Tusa interview).

17 Leo Benítez, Revista Béisbol Profesional (Caracas: Cadena Capriles, 1978).

18 Gil-Tusa interview.

19 “Venezuelan Keystone Combo,” The Sporting News, June 4, 1966: 36.

20 Russell Schneider, “Vet Pilot Lipon Hottest Booster of Infielder Gil,” The Sporting News, February 25, 1967: 20.

21 Schneider, “Vet Pilot Lipon Hottest Booster of Infielder Gil.”

22 Gil-Tusa interview.

23 Gustavo Gil, Dámaso Blanco and Freddy Rivero were exchanged for Everest Contramaestre, Gustavo Espósito, Alonso Olivares, and Roberto Romero. Alfonso Tusa, “Una Temporada Mágica” (Caracas, Liga Venezolana de Beisbol Profesional, 2006).

24 Gil-Tusa interview.

25 “Deals of the Week,” The Sporting News, June 1, 1968: 35.

26 The Sporting News’s Player Contract Card for Gustavo Gil, https://digital.la84.org/digital/collection/p17103coll3/id/43770/rec/1 (last accessed October 10, 2021).

27 Gil-Tusa interview.

28 Tusa-Tusa interview.

29 Gil-Tusa interview.

30 García, Giner, Emil Bracho, and Luis Sequera, “99 + 1”.(Caracas, Fundación Magallanes de Carabobo, 1996).

31 Gil-Tusa interview.

32 Maza-Tusa interview.

33 “Major Flashes,” The Sporting News, July 24, 1971: 35.

34 Benítez, Revista Béisbol Profesional.

35 Benítez, Revista Béisbol Profesional.

36 Gil-Tusa interview.

37 Gutiérrez F, Daniel, Efraim Álvarez, and Daniel Gutiérrez, “La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela” (Caracas, 2006).

38 Gutiérrez, Álvarez, and Gutiérrez, “La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela.”

39 Gutiérrez, Álvarez, and Gutiérrez, “La Enciclopedia del Béisbol en Venezuela.”

40 Gustavo Gil Profile, Baseball Cube, http://www.thebaseballcube.com/players/profile.asp?ID=11876&View=Jobs (last accessed October 10, 2021).

41 Bill Reader, “Seattle Pilots, Where Are They Now?” Seattle Times. July 9, 2006, https://archive.seattletimes.com/archive/?date=20060709&slug=pilotsbios09 (last accessed October 10, 2021).

42Venezuelan Baseball Hall of Fame, Gustavo Gil Profile, http://museodebeisbol.com/salon_fama_venezolano/detalles/2008/gustavo-gil (last accessed October 10, 2021).

43 “Falleció Gustavo Gil, la leyenda del Magallanes,” Analítica, December 8, 2015, https://www.analitica.com/deportes/fallecio-gustavo-gil-la-leyenda-del-magallanes/ (last accessed October 10, 2021).

Full Name

Tomas Gustavo Gil Guillen

Born

April 19, 1939 at Caracas, Distrito Federal (Venezuela)

Died

December 8, 2015 at Phoenix, AZ (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.