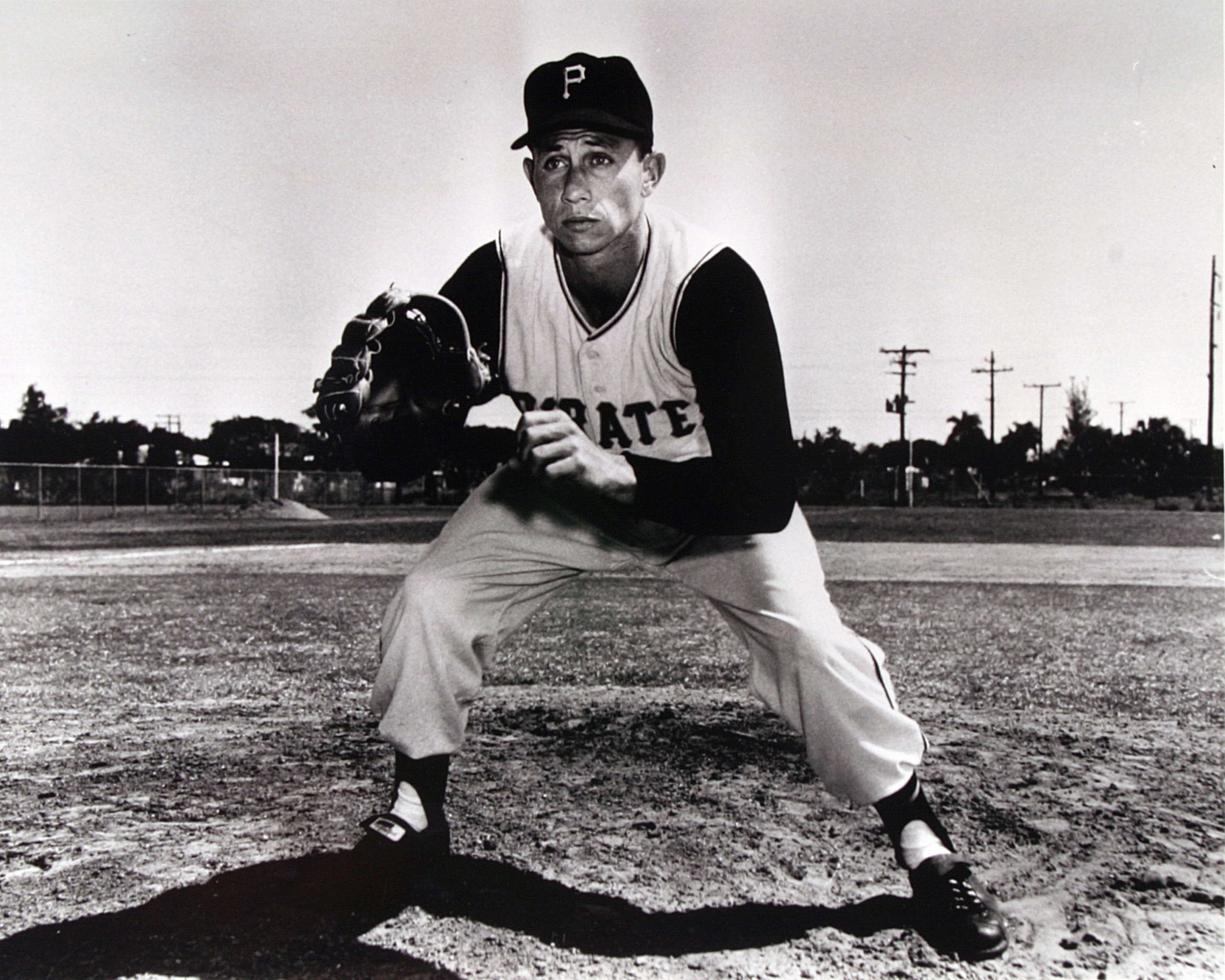

Harvey Haddix

Whenever the name Harvey Haddix is mentioned, there is usually a reference to a 115-pitch game he threw in Milwaukee in 1959. His career in professional baseball, however, was much more — lasting parts of five decades.

Whenever the name Harvey Haddix is mentioned, there is usually a reference to a 115-pitch game he threw in Milwaukee in 1959. His career in professional baseball, however, was much more — lasting parts of five decades.

Haddix was born on September 18, 1925, the third son of Harvey Haddix, Sr. and Nellie Mae Greider-Haddix. His parents were farmers near Westville, in west central Ohio, but Haddix was born 20 miles away, in Medway, Ohio. “My mother had an aunt who was a midwife who lived there,” Haddix explained in a public appearance in 1989.

Life on the farm was typical for the Haddix boys, Harvey, older brothers Ed and Ben, and younger brother Fred. “There on the farm we didn’t have any money and there were no kids out there to play ball with, except the neighbor kids, so we played baseball two on a side.” His first glove was a first baseman’s mitt made from a leather horsecollar.1

In 1940, before his freshman year in high school, the family purchased a farm near South Vienna, Ohio. Catawba High School had a successful baseball team loaded with upperclassmen, including brother Ben. Harvey became the team’s left-handed shortstop, “I could catch a ground ball,” he explained. 2

Equipment continued to be an issue. Haddix elaborated: “I made the ball team but I didn’t have a pair of spikes so I took a pair of my dress shoes and punched holes in the bottom of my dress shoes and riveted cleats on the bottom for my first pair of spikes.”3

As a senior he began to pitch. “When I became a senior the pitcher had graduated so I took over the pitching chores and we won the county championship.” He had an excellent instructor at home in the person of his father, who was a renowned amateur pitcher.4 Brother Ben, two years older, was playing minor-league baseball for the local Springfield Cardinals, a Class C Middle Atlantic League club managed by Walter Alston.

In 1943, after Haddix graduated from high school, “I was pitching, semipro, and a scout was there from the Philadelphia Athletics. He comes to me and says, ‘I am going to write Connie Mack about you.’ I said, ‘That would be fine’ and I sat around waiting for two weeks and didn’t hear anything. One day I picked up the newspaper and there was a little article in the paper that said that there is a Redbird tryout in Columbus.

“I had to go to Columbus, at 9 in the morning until 4 in the afternoon for the tryout camp. They had 350 kids there. … They looked at me and said you will be a pitcher. Pitchers went down to the bullpen, and we sat there until 4. They said: OK warm up and go in and throw nothing but fastballs. They said, ‘Can you come back tomorrow?’

“I came back the next day. Now throw what the catcher calls. I probably threw three to four curveballs, and three to four fastballs. As I walked off the mound he says, ‘Do you want to sign?’ I said no. I am an old country boy, I am thinking about the guy back home that saw me first. I never heard anything more from him and went back over to Columbus and signed with the Cardinals.

“Now (World War II) was going on and I took a two-week trip with the Columbus baseball club. I just turned 18 so I had to leave the trip in Louisville and return to Springfield to register for the draft.”5

Haddix’s next road trip would have to wait three years. As a farmer he received a three-year deferment from military service, which meant his only employment could be the farm.

In 1947, after the war ended, Haddix started his professional baseball career, in Triple-A. “I took off for Columbus for spring training. Now I know I can’t play with them, I sat there about two weeks and I finally had enough and went up to the office and said, ‘Where am I going to go play ball?’ He said you are going to Pocatello, Idaho. I looked at him and said, ‘No I’m not. That is too far from home. You got something closer to home than that.’ ”

A couple of days later Haddix was sent to Winston-Salem of the Class C Carolina League and met the team in Lynchburg, Virginia. “I got there and was setting on the steps waiting for someone to come and here comes a little old school bus with Winston-Salem Cardinals on the side of it. There was one guy on the team that knew me who introduced me to the manager (Zip Payne).” Haddix was 5-feet-6, 175 pounds, and Payne’s first impression was not positive. Haddix said he was told the manager said, “Do they expect me to win a pennant sending me something like that down here?” 6

Haddix’s first two appearances were in relief. He did not allow a run in a win and a loss. From then on he was a starter and changed the manager’s opinion by winning 19 and losing 5, with 275 strikeouts while also hitting over .300 (including a pinch-hit homer). On August 11 he pitched a seven-inning no-hitter, later threw a nine-inning one-hitter, and had a 19-strikeout game. He was selected a league all-star, the left-handed pitcher of the year, the rookie of the year, and the most valuable player. His 1.90 ERA easily beat out the second-best (3.18).

“The next year I jumped to Triple-A ball. I pitched there for three years, ’48, ’49, and ’50. Now I thought I was good enough to go to spring training with (the Cardinals) but the Cardinals didn’t want to see me. They had five good left-handed pitchers (Harry “The Cat” Brecheen, Max Lanier, Howie Pollet, Al Brazle, and Ken Johnson.)” 7

In Columbus Haddix got the nickname “Kitten.” General manager George Sisler Jr. called him “a second Brecheen,” adding, “Won’t that be something when he joins the Cards and teams up with Brecheen to pitch a doubleheader? ‘The Cat and the Kitten.’ ”8

As Haddix matured he had grown a little and was generously listed at 5-feet-9. In 1948 at Columbus he had 11 wins and a .337 batting average. For a second straight year he was an all-star. Cardinals catcher Joe Garagiola said, “I don’t know how far Haddix is away from the majors, but I do know he will be there one of these days.”9

The 1949 season was more of the same. Haddix won 13 games for the Red Birds and was again selected an all-star. In 1950 he had 18 wins and another all-star selection, as he added a change-up to his repertoire of pitches, which included a fastball and slider. On August 16 for Columbus he retired 28 Milwaukee Brewers batters in a row during an 11-inning game. Retiring more than 27 Milwaukee batters in a row in an extra-inning game might come up again in his future.10

On September 9 the playoff-bound Red Birds had Harvey Haddix Day. It was also announced that his contract had been sold to the Cardinals. But a trip to St. Louis would have to wait as he was drafted into the Army and sent to Fort Dix, New Jersey. He got leave to travel to Baltimore to pitch for Columbus in a Junior World Series game. The Orioles were not accommodating, taking the game 8-1.

Haddix served as a Fort Dix athletic director in 1951 and 1952, and managed and pitched for the camp baseball team. In 1952 he led the team to the state semipro championship. In August, his Army service complete, he joined the Cardinals and made his major-league debut on the 20th in St Louis against the Boston Braves, winning a complete-game five-hitter, 9-2. He finished the season with three complete games, a 2-2 record and a 2.79 ERA. He singled in his first big-league at-bat.

To make up for lost time, Haddix headed to winter ball in San Juan, Puerto Rico. He threw shutouts his first two starts and when the Cardinals shut him down December, he was 6-2. He was so popular that the team threw a banquet in his honor.

Haddix entered spring training in 1953 as the Cardinals’ top prospect, coming to camp in great shape and having a great spring. He even won a box of cigars for winning three pitcher’s batting awards: collecting the most hits, scoring the most runs, and stealing the most bases.

Haddix opened his rookie season in the starting rotation and shut out the Chicago Cubs on a four-hitter in the Cardinals’ home opener. By June 27 Haddix had won ten games and led the team with 79 strikeouts. He earned a spot on the National League All-Star team, but didn’t pitch in the All-Star Game. Returning to action after the game, Haddix threw five straight complete games from July 19 through August 6. The August 6 game was a two-hitter against the Phillies, both Phillies hits coming in the ninth inning. Richie Ashburn, who got the first hit, created controversy by trying to bunt his way on. Haddix’s only comment was, “He was only trying to win, that’s all.”11 Haddix finished with 20 wins, 19 complete games, six shutouts (leading the league), and a 3.06 ERA, while batting .289. He was second to the Dodgers’ Jim Gilliam for Rookie of the Year. Gilliam said he was surprised to have won.12

Cardinals manager Eddie Stanky was happy with his southpaw. “What can I say about the guy? He can run, hit, and field better than most pitchers. … What more can you expect?”13 Haddix won three new suits from Stanky, who had challenged his pitchers to pitch complete games with no walks.

Haddix again ranked among the elite National League pitchers in 1954. Again selected a National League All-Star, he had to be replaced on the team due after being struck below the right kneecap by a line drive off the bat of someone who would play a significant role in his future, Milwaukee first baseman Joe Adcock. Haddix said the injury bothered him the rest of his life and affected his pitching. “I was never the same after that,” said Haddix. “I didn’t have the same spring off the mound.” 14

Haddix had won 12 games at the time of the injury. He won only six games the rest of the season but ended on a high note, pitching nine shutout innings against Milwaukee in a no-decision and winning his 18th on September 19 with one inning of relief.

In February Haddix said his injury had healed and was giving him no trouble during the hunting season, but added, “After the leg was hurt I couldn’t run well and my conditioning suffered. A pitcher is still only as strong as his legs.”15 And Haddix and the Cardinals got off to rocky starts.

The team began 9-12 start in a rainy spring. Haddix and Brooks Lawrence made 15 appearances as starters or relievers in the first 21, games winning only two. Haddix’s ERA was 5.91.

The Cardinals’ slow start got manager Stanky fired and replaced by Harry Walker. Haddix’s record stood at 2-8, so he spent hours throwing pitches against the outfield wall trying to harness his curveball. Giants coach Frank Shellenback gave him a tip about gripping his curveball. This, plus the fact that he learned he was tipping his pitches helped him turn around his season to some extent.

Despite his poor record (6-9 and a 5.43 ERA), Haddix was selected to the National League All-Star team and for the first time pitched in the game. It would be his sixth and final time as an All-Star. He ended a disappointing season with a 12-16 record and a 4.46 ERA, still good enough for new general manager Frank Lane to call him a Cards untouchable. He would also enter the 1956 season with his new wife, Marcia Williamson. After a honeymoon and a winter of hunting at his South Vienna farm, he entered 1956 spring training ready to go. But on May 11 the “untouchable” was traded to the Philadelphia Phillies with pitchers Stu Miller and Ben Flowers for pitchers Herm Wehmeier and Murry Dickson.

“I didn’t want to go to the Phillies,” Haddix said in 1989. “But good things come out of bad things. I had a house free of rent there, and with the money I saved the two years in Philadelphia, I bought my first farm.”16

After pitching coach Whit Wyatt noticed some mechanical flaws in his motion, he regained his form. He had a 12-8 record, and could have been 16-4 if the Phillies bullpen had not blown four leads. Phils manager Mayo Smith listed the acquisition of Haddix as the year’s most pleasant surprise.17

Haddix was inconsistent in 1957. At times he was the staff ace, but later he was sent to the bullpen. In July he pitched an 11-inning shutout against the Cubs, but in his next game he was knocked out by the Braves in the third inning. He ended the season with a 10-13 record and a 4.06 ERA, and he suffered with a stiff arm for the first time in his career. In the offseason the Phillies, needing hitting, traded Haddix to Cincinnati for slugger Wally Post. “I figured at the end of last season that I would be traded,” Haddix said. “I thought I would go to one of any four clubs, but going to the Reds is the best that could have happened. … The Reds have always been my team, even when I was a kid.”18

For Haddix, 1958 was another season with flashes of greatness and mediocrity. He went to a no-windup delivery to try to stop the recurring problem of tipping his pitches. “I cut down the windup so I could hide the ball from the third base coach,” he said.19 For the season he was 8-7 with a 3.52 ERA and gave up 191 hits in 184 innings, including 28 home runs. On the brighter side, he received his first Gold Glove Award. Then in January he was traded with catcher Smokey Burgess and third baseman Don Hoak to the Pirates for Frank Thomas, Whammy Douglas, Jim Pendleton, and Johnny Powers.

The Pirates were poised to contend. Haddix got off to a hard-luck, start, with poor run support. On May 26 his record was 4-2 with a 2.67 ERA. On that day he was scheduled to pitch against the Milwaukee Braves in Milwaukee. He had the flu, spent most of the chilly, windy, and rainy day in bed and if he hadn’t been pitching would not have gone to the ballpark.

In their pregame meeting to go over hitters Don Hoak said, “Harve, if you pitch the way you say you will, you’ll have a no-hitter.”20 Matched against the Braves Lew Burdette, he did just that. After 12 innings he hadn’t allowed a baserunner. But the run support, lacking all spring, was still lacking this night, and going into the bottom of the 13th inning, the game was still scoreless. The end came quickly for Harvey. In that fateful inning, the Braves’ leadoff hitter, Felix Mantilla, reached on a wild throw by Hoak. Eddie Mathews bunted Mantilla to second and Henry Aaron was given an intentional walk, bringing Joe Adcock to the plate, the same Adcock who had smashed a line drive off Haddix’s knee in 1954. On a one-ball, no-strike pitch, Adcock hit Haddix’s 115th pitch of the night into the right-center-field bleachers. On a base-running blunder, Adcock was called out and credited with a double when Aaron left the basepath and was passed. The final score was 1-0.

Haddix was amazed to find out he had broken the record for consecutive perfect innings to start a game. “Who, me? All I know is we lost. What is so historic about that?”21 He turned down an opportunity to appear on the television shows To Tell the Truth and The Ed Sullivan Show feeling it more important to stay with the team. But accolades came from all over the country. National League President Warren Giles presented him with an inscribed silver tea service with 13 cups. Few days would pass the rest of his life when Haddix wasn’t asked about the game.

Meanwhile, as the season wore on, Haddix’s pitching faltered. He continued to receive little run support and ended the season 12-12 but with a 3.13 ERA. For the second consecutive year, he was recognized for his fielding with the Gold Glove Award. “Haddix really never pitched a bad game for us all year,” said manager Danny Murtaugh. “I figured on him for 12 victories but he was consistently good. We just didn’t score many runs for him.”22

The 1960 season began with high expectations for the Pirates, especially if the talented outfielder Roberto Clemente could stay in the lineup. The Pirates were a tight-knit cast of characters. After every win Roy Face would strum his guitar while Fred Green, Bill Mazeroski, Bill Virdon, Jim Umbricht, Gino Cimoli, and Haddix harmonized. To a man, they would all say it was the best group of players they ever played with. Vern Law said, “Harve was a fun guy – well liked by everyone.”23

The only question on Haddix’s performance was a lack of stamina. His answer: “I’ve been a seven-inning pitcher at times because I’m a little man and have to work harder out there than some other fellows. I can’t afford to coast.”24 Haddix made 28 starts but had only four complete games and finished with an 11-10 record and a 3.97 ERA. Supplemented by midseason acquisition Vinegar Bend Mizell, the Pirates clinched the pennant on September 25.

Going into the World Series against the Yankees, New York first baseman Dale Long, a former Pirate, asked about the Pirates’ pitchers: “The one Pittsburgh pitcher who would be likely to make trouble for our team is left-hander Harvey Haddix.”25 Haddix made Long sound like a prophet. He started and won Game Five, pitching into the seventh inning giving up two runs as the Pirates won, 5-2. The victory gave the Pirates a 3-2 lead in the Series. The Yankees won Game Six, and for the seventh game Haddix found himself in the bullpen. In the top of the ninth, with the Pirates leading 9-7, Haddix relieved Bob Friend after the first two Yankees batters got hits. “That was the only time in my life I was really nervous,” Haddix said. “The hair stood up on the back of my neck.” 26

Roger Maris was the first batter he faced. “Maris is in there squeezing the sawdust out of the bat and he can’t wait to get to me,” Haddix recalled. “They were so anxious to hit. I’m talking to myself: ‘This is something you have waited for your whole life and now you are going to blow it because of nerves.’” 27

Haddix got Maris to pop out to the catcher. Then Mickey Mantle singled in a run, and his savvy baserunning on a grounder by Yogi Berra allowed the tying run to score. Haddix retired the side, and when Bill Mazeroski homered in the ninth, Haddix got the victory. He called it his career highlight. Offseason highlights included an $8,400 World Series check and birth of his second child.

The Pirates were favored to win again in 1961, and though Haddix won 10 games and a third Gold Glove, some wondered whether the 34-year-old, nine-year veteran was on the downside of his career. Haddix’s innings pitched had dropped to 172⅓ in 1960 and 156 in ’61. The team fell to sixth place, a disappointing four games under .500. In September Haddix was moved to the bullpen as manager Murtaugh wanted to see how he reacted to late-inning relief. He was paired with Roy Face to finish games. “I don’t find it so bad,” he said after the season. “I think I can do the job if that is what they want of me.”28

In 1962 the plan was for Haddix to stay in the bullpen but an injury to Vern Law changed the plan and Haddix started 20 times in 29 appearances totaling 141⅓ innings, winning nine games and losing six. Although the Pirates won 93 games (in the National League’s first 162-game season), they finished in fourth place, behind the Giants, Dodgers, and Reds. Haddix’s mother, Nellie, died on June 22. Whether coincidence or not, he struggled for the remainder of the season, which he attributed to losing control of his curveball.

In 1963, the 37-year-old Haddix was the oldest player on the team, and was in the bullpen full time, except for one start. In August teammate Vern Law retired and it appeared the Pirates were preparing to jettison other veterans as they started to rebuild. Haddix pitched 70 innings and ended with three wins, one save, and a 3.34 ERA. The Pirates finished eighth. His relief stint on September 21 turned out to be his last game with the Pirates. On December 14 he was traded conditionally to the Baltimore Orioles for minor-league shortstop Dick Yencha and cash. Although he would always consider himself a Pirate (“A part of me belongs in Pittsburgh”29), he said, “It’s all right. Wherever there is money I’ll go, although this will be my first appearance in the American League.”30

Haddix’s fastball was back in spring training. The Orioles plan was for him to be the left-handed complement to Dick Hall in the bullpen. His career was rejuvenated. For the third-place Orioles in 1964 he pitched 89⅔ innings, all in relief, and had five wins, ten saves, and a 2.31 ERA. He was the runner-up for the Gold Glove Award. (Haddix’s offseason highlights included shooting a 900-pound buffalo owned by a neighbor when it ran wild and attacked their cows.)

After such a strong comeback, few might have imagined that 1965 would be Haddix’s last as a pitcher and would end with a trade to the team that had broken his heart six years earlier. Haddix hurt his arm in spring training. “It never got well,” he said. “Sometimes it was the shoulder, sometimes the elbow hurt. I didn’t pitch much but I used it all the time, hoping work would help, but it didn’t.”31 On August 30, Haddix was sold to the Milwaukee Braves, who were fighting for the pennant. Out of sheer honesty, he refused to report and retired instead. “I’d have finished the season if I could have, but there wasn’t much sense in changing when I knew I couldn’t help a new club the way my arm was feeling,” he said at the time. “I wouldn’t mind trying again next spring. Or I’d love to catch on with a team looking for a pitching coach.”32 His last big-league appearance was on August 28, 1965.

In November Haddix hired on as the pitching coach of the Vancouver Mounties, the Oakland Athletics’ Triple-A team. But on December 29 he resigned and signed as pitching coach of the New York Mets. He would be the first big-league pitching coach for Tug McGraw, Nolan Ryan, Tom Seaver, and Jerry Koosman. In 2009 Ryan said, “Harvey could not have been, from my perspective, more of the right person at the right time for me.”33

After two ninth-place (out of ten) finishes, Mets manager Wes Westrum was fired near the end of the 1967 season and new manager Gil Hodges replaced the entire coaching staff. Haddix went back to the Pirates’ organization in 1968 and coached the Columbus Jets and the Gulf Coast League Pirates. In 1969, he became the Cincinnati Reds’ pitching coach. When Reds manager Dave Bristol was fired at the end of the season, it meant back to the minors with Pittsburgh for Haddix. The Boston Red Sox hired him as pitching coach in 1971, but at season’s end his wife, Marcia, persuaded him to retire. But when Frank Robinson asked Haddix to join him for his historic managerial tenure in Cleveland, Haddix unretired. From 1975 to 1978, he was the Indians’ pitching coach. In 1979 Haddix joined Chuck Tanner and his beloved “Family” – the Pirates – for the next six seasons, getting his second World Series ring in 1979.

A heavy chain-smoker, who described cigarettes as his best friend, Haddix developed emphysema. This hastened the end of his baseball career and eventually his life. Even though his 1984 Pirates pitchers led the league in ERA, he was fired because thrifty general manager Syd Thrift wanted coaches who could also throw batting practice. Haddix no longer was able. His health continued to deteriorate but he never stopped smoking. He died on January 8, 1994, in Springfield, Ohio. “I loved cigarettes, but they finally got to me,” he said a year or so before his death.34

In 1999 fans voted Harvey Haddix the left-handed pitcher on the Pirates’ All-Century Team to celebrate a career that consisted of much more than the 115 pitches thrown on a rainy night in Milwaukee.

This biography is included in the book “Sweet ’60: The 1960 Pittsburgh Pirates” (SABR, 2013), edited by Clifton Blue Parker and Bill Nowlin. For more information or to purchase the book in e-book or paperback form, click here.

Sources

Books

Jim O’Brien, Maz and the ’60 Bucs (Pittsburgh: James P. O’Brien Publishing Co., 1993).

Newspapers or magazines

Dayton (Ohio) Daily News, September 9, 1965

Springfield (Ohio) Daily News, 1947-1979.

Springfield (Ohio) Sun, 1947-1979.

The Sporting News, 1947-1994.

Urbana (Ohio) Daily Citizen. May 27, 1992.

Online sources

DVD, Wright State University Major League Baseball Panel Discussion, April 17, 1989, produced by Professor Allen Hye, 2009 (Cited as WSU Panel Discussion).

Letters

Letter from Nolan Ryan to Springfield/Clark County Baseball Hall of Fame. May 4, 2009.

Letter from Vern and VaNita Law to Springfield/Clark County Baseball Hall of Fame. January 8, 2009.

Other

Several discussions between the author and Harvey Haddix on numerous occasions in various settings. These were undocumented as both were acquaintances from the same community.

Notes

1 WSU Panel Discussion.

2 WSU Panel Discussion.

3 WSU Panel Discussion.

4 WSU Panel Discussion.

5 WSU Panel Discussion.

6 WSU Panel Discussion.

7 WSU Panel Discussion.

8 The Sporting News, July 21, 1948, 11

9 The Sporting News, September 8, 1948, 21

10 The Sporting News, August 30, 1950, 22

11 The Sporting News, August 18, 1953, 7

12 The Sporting News, January 6, 1954, 8

13 The Sporting News, September 9, 1953, 12

14 Jim O’Brien, Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 465

15 The Sporting News, February 16, 1955, 19

16 WSU Panel Discussion

17 The Sporting News, September 19, 1956

18 Springfield Daily News, December 7, 1957, 2

19 The Sporting News, June 4 , 1958, 4

20 WSU Panel Discussion

21 O’Brien. Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 463

22 The Sporting News, November 11, 1959, 16

23 Vance Law letter

24 The Sporting News, August 31, 1960, 18

25 The Sporting News, September 28, 1960, 10

26 Quoted in O’Brien, Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 462

27 Ibid.

28 The Sporting News, January 10, 1962, 23

29 O’Brien, Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 468

30 The Sporting News, December 15, 1963, 15

31 Dayton Daily News, September 9, 1965, 22

32 Ibid.

33 Nolan Ryan letter

34 O’Brien. Maz and the ’60 Bucs, 458

Full Name

Harvey Haddix

Born

September 18, 1925 at Medway, OH (USA)

Died

January 8, 1994 at Springfield, OH (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.