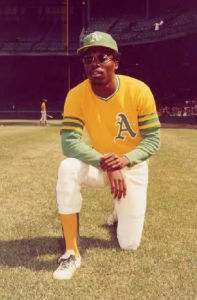

Herb Washington

Charles O. Finley indulged in many whims as owner of the A’s—and hiring world-class sprinter Herb Washington was one of his most fanciful experiments. Washington’s stint with Oakland (1974 and early 1975) was just part of Finley’s longstanding infatuation with “designated runners.” The track star was the second of six specialists whom the A’s employed in this role from 1967 through 1978. Washington didn’t have the longest tenure—Allan Lewis did—but he got by far the most press.

Charles O. Finley indulged in many whims as owner of the A’s—and hiring world-class sprinter Herb Washington was one of his most fanciful experiments. Washington’s stint with Oakland (1974 and early 1975) was just part of Finley’s longstanding infatuation with “designated runners.” The track star was the second of six specialists whom the A’s employed in this role from 1967 through 1978. Washington didn’t have the longest tenure—Allan Lewis did—but he got by far the most press.

That status was often controversial. Washington came to Oakland without having played baseball since the summer between his sophomore and junior years in high school.1 His presence on the roster raised even more eyebrows—and voices—among teammates than Allan Lewis had during his six partial seasons with the A’s. The other specialists appeared on occasion in the field or at bat, but Washington never did either. What’s more, the pure speed of “Hurricane Herb” did not translate into high base-stealing success—he swiped 31 in 48 attempts (65 percent).

As a result, his statistical value was slightly negative, and the team could well have benefited more from a more fully rounded reserve. Yet looking back, Washington contended, “If you ranked the players on that team [in 1974] from 1 to 25, I think my value was higher than the 25th player. If I was the 25th in terms of value, I’ll take it.”2

Nonetheless, Washington’s baseball career was a unique and memorable oddity—no other baseball card besides his 1975 Topps entry has shown “Pinch Run.” as a player’s position. Much more significant, though, is how this bright and personable man went on to great success in business. Washington’s company, H.L.W. Fast Track, Inc., became the largest African-American-owned McDonald’s franchisee in the United States. He has given much back to his community and schools. “Life’s pretty good,” he said contentedly in 2014.3

Herbert Lee Washington was born on November 16, 1951, in Belzoni, Mississippi. This is a small town in the Delta region on the Yazoo River; today the area is best known for catfish farming. Herb was the eldest of four children born to Willie B. Washington and his wife, Mary (née Haynes). He had a brother named Willie and two sisters, Georgia and Renea.

The Washington family moved to Flint, Michigan, when Herb was around one year old. His parents sought work in the auto plants. “Washington worked there too, for two summers, and learned the one thing he didn’t want to do for a living.”4

Herb grew up on the north side of Flint and attended Parkland Elementary School and Emerson Junior High. He first realized that he had truly exceptional speed “probably when I was 11 years old, I was in fifth grade.”5

After going to Northern High School in Flint for a year, he had to transfer to the city’s Central High School because of an issue with school boundaries. He then began to compete in indoor track meets all over the country. In March 1968, in Milwaukee, the 16-year-old ran the 50-yard dash in 5.1 seconds. His time was tied with Charlie Greene, who won an Olympic gold medal in the 4×100 relay several months later, but Greene was declared the winner. Herb’s track coach at Flint Central, Carl Krieger, said, “The pictures in the papers the next day proved Washington won.”

Of greater interest, though, were Krieger’s comments on Washington as a person. “Herb is good because he’s intensely competitive. He has drive and concentration. Charlie Greene is noted for trying to unnerve his opponents and he tried it on Herb at Milwaukee. But it didn’t work. Herb has superb legs and he trains hard. He’s an intense listener and follows directions. There’s not much more you can ask.”6

Washington ran another 5.1 50 later in March—an unofficial world record.7 After graduating from Flint Central, he attended Michigan State University in the state capital, Lansing. In 2004 he remembered, “My dad once told me that ‘If Michigan State is dumb enough to offer you a scholarship, you better be smart enough to come home with a degree.” Herb stressed the need to prepare student-athletes if they couldn’t make it to the next level. “An injury can take your playing career away, but they can’t take your education away.”8

Washington earned a B.S. degree in education.9 In addition, he met his wife-to-be, Gisele Gibbs, at MSU. Herb was still a bachelor while he was with Oakland; the couple got married on May 24, 1980. They had two children, a son named Terrell and a daughter named Arielle, who both also went to MSU.

As a freshman, Washington lost a race to another 1968 Olympian, John Carlos (best known for his Black Power salute on the medal stand in Mexico City). It was a big lesson, as Herb remembered in 2007. “I’d never been run down from behind. I’m in tears. And Carlos comes up to me and says, ‘Schoolboy, you just stopped running.’ I never forgot that.”10

Washington played wide receiver for the Spartans football team as a sophomore and junior. Ahead of the 1969 season, he caught a long touchdown pass in the Green-White intrasquad game.11 A report a couple of days later added that he had been making some fine catches in practice as a flanker.12 However, he had just one reception—for 41 yards—in a regular-season game. He quit the heavily run-oriented team in October 1970 after appearing in just one game as a junior.13

Track remained Washington’s main focus in college. In February 1970, at the Michigan State Relays, he beat John Carlos in a rematch.14 The following month, the 18-year-old again tied his record of 5.1 seconds in the 50-yard dash—twice.15 In February 1971, he tied the world record in the 60-yard dash, again at the Michigan State Relays.16

Though Washington had bypassed football as a senior, his extraordinary speed was still attractive to the National Football League. Especially after Olympic gold medalist Bob Hayes became a star with the Dallas Cowboys in the 1960s, many teams took a flyer on sprinters. On February 2, 1972, the Baltimore Colts selected Washington in the 13th round (out of 17) of the NFL draft. He was asked to report to a Colts orientation in early March, but informed the club that he was committed to competing in the Big Ten Conference meet.17 Plus, Washington’s big goal in 1972 was to make the US Olympic track team, and at that time amateur status was a much stricter requirement.

Just two days after being drafted, Washington set a new world indoor record of 5.0 seconds in the 50-yard dash, which also tied the outdoor mark.18 A mere eight days later, he set the world indoor record in the 60-yard dash, once more at the Spartan Relays meet. His time of 5.8 seconds beat his own best of 5.9—a mark originally set in 1964 by none other than Bob Hayes.19

In late June and early July, the Olympic track trials took place in Eugene, Oregon. Many talented sprinters were competing, and Washington finished fifth in the finals in his event, the 100 meters.20 In 1974, he admitted to being nervous. He added that at that time, he was better sprinting indoors than outdoors.21

The disappointment in Eugene meant that Washington was free to go to the Colts’ pre-season training camp, which began on July 19. Newspapers reported that he mulled over Baltimore’s offer but left immediately after reporting because he still had hopes of gaining a spot on the Olympic team (ostensibly as an alternate).22 In 2014, however, Washington said, “We couldn’t agree to a price—simple as that. What they were offering for a signing bonus was an insult. I made more than that under the table running track!”23

In February 1973 Washington equaled his own world indoor record in the 50-yard dash. It came in the same place as his mark from a year before, Toronto. He continued to compete in Amateur Athletic Union (AAU) events over the course of the year. Hasely Crawford, the 1976 Olympic gold medalist from Trinidad and Tobago, beat Herb in February—but for the rest of the year, Washington didn’t lose a single sprint.24

That December, Oakland assigned pinch-runner Allan Lewis outright to Triple-A Tucson, and he never played again. Going into the 1974 season, however, Charlie Finley still wanted a pinch-runner on the A’s roster. Alvin Dark (who had been named to replace Dick Williams as manager in February 1974) suggested Washington, whom he had seen win many televised races.

Washington had been working as a TV and radio broadcaster with WJIM in Lansing. Late that January, he said, “The big thing is the last letter in my station’s call letters—M for money. If the bonus is big enough, I’ll become a pro [in track]. I hope to break the world record in the 50 at Toronto. That should make me more salable.”25 At various points in 1974, press articles said Washington had been competing on the pro track tour, but that was not so. The International Track Association (ITA), a professional circuit, was founded in 1973, but Washington did not join it until after the 1974 season.26

Despite his layoff, Herb was still interested in pro football. The brand-new World Football League was getting ready to play its first season, and in February 1974, Washington expressed a desire to try out for the Michigan franchise, the Detroit Wheels.27 He also said that he was on the verge of signing with the Toronto franchise—but then Finley called.28

“When I got the message, I thought it was a joke,” Washington recalled in 2007. “Then, I got paged. He said, ‘Herbie, I want you to play baseball and be a pinch-runner.’ I said, ‘Mr. Finley, I’m going to need a no-cut contract. I know sometimes you just get rid of people.’ He said, ‘A no-cut contract? The only players who have those are Vida Blue, Catfish Hunter and Reggie Jackson! Are you telling me you’re in the same league as those guys?’ I said, ‘No, but none of those guys can outrun me.’”29

Finley predicted, “I feel [Washington] will be personally responsible for winning ten games this year.”30 According to a January 1975 article, Alvin Dark counted nine games that Herb won for the A’s by stealing a base that eventually led to the lead or winning run. A’s captain Sal Bando, Washington’s most outspoken critic, sniped, “Yeah, but how many games did he lose?”31 In retrospect, Washington’s calm but pointed comment was, “A captain is supposed to lead by example.” As for Dark, he said, “I had a very positive personal experience with Alvin.”32

The truth lay somewhere in between Dark’s hyperbole and Bando’s negativity. “Finley’s Folly” came on to run in 92 games in 1974; a play-by-play study shows that many of his 29 runs scored came when his team was already comfortably ahead. His finest moment came on August 2; at Chicago, he scored the go-ahead run in the eighth inning after stealing second and coming home from there on a single. Vida Blue made the lead stand up.

Herb scored the winning run in two other games (on June 22 and July 3), but his speed was not a factor in either tally. In several other games, his runs scored were significant parts of victory, either helping the A’s to come back, tie the game, go ahead, or gain needed insurance. The most notable of those came on July 8, at home against Cleveland. Gaylord Perry, who was riding a 15-game winning streak, took a 3-2 lead into the ninth inning. But with one out, Joe Rudi tripled, and the tying run came in because Washington entered and his speed enabled him to come home on a short sacrifice fly to left-center. “George Hendrick said he was going to throw me out, and he threw the ball into the backstop,” Washington remembered with a laugh.33 The A’s then beat Perry in the tenth.

On the flip side, when Herb was caught stealing (16 out of 45 attempts), most of the time it didn’t do any damage. There were three exceptions, when he got nailed while representing the tying run in pitchers’ duels that the A’s lost (on August 11, August 19, and September 25).

With his minimal baseball experience, Washington had to overcome several obstacles. The first was learning how to shift gears and turn on the basepaths, as opposed to blasting straightaway as he could do on the track. The second was learning how to slide. The third and most important was learning about the pitchers and catchers and how to pick his opportunities. “I have a world of reactions I’ve got to hone down to where they’re instinctive,” he told Sports Illustrated in June 1974.34

To start that process, the A’s brought in one of the all-time greatest baserunners, Maury Wills. Looking back after the season ended, Washington said, “I only had six days in training camp with Maury. … It was a cram session and I didn’t begin to relate to many of the things he talked about until July.”35 He didn’t get the hang of feet-first sliding and stuck with going in headfirst.36

Washington did shag balls in the outfield during batting practice (upon the signing, Finley had talked about the possibility of giving him some action there). He also got to take some swings in BP. Still, many stars—such as Reggie Jackson, Gene Tenace, and Texas Rangers pitcher Ferguson Jenkins—said in so many words that Washington wasn’t a ballplayer, and that he was taking a roster spot that belonged to a pro who had paid his dues.37

Washington didn’t get the cold shoulder from everyone, but eventually the grumbling prompted him to stand up for himself in a team meeting, showing the confidence and pride he had developed as a sprint champion. As a result, he could sit in the back of the team bus and give as good as he got in the repartee with Bando and Tenace.38 “Gene Tenace was always good-natured about the riding,” Washington recalled. “It was just what the ‘rook’ had to go through.”39 His teammates also gave Herb a glove and bat to dress up his locker.40

Having a good sense of humor helped Washington’s situation a great deal. One of his favorite memories of his time with the A’s featured an opposing catcher, Thurman Munson of the New York Yankees. Munson had a solid record of throwing out enemy base stealers: 38 percent lifetime, with very little fluctuation from year to year. Yet Washington was 3-for-3 against the Yankee captain-to-be, who also committed two throwing errors on those thefts. As Herb told the story in both 2002 and 2004, Munson told him before one game, “My grandmother could throw you out.”

The next day during batting practice, Washington said, “Hey Thurman, there’s a call for you in the clubhouse.” After a suspicious Munson asked who it was, Herb responded, “It’s your grandmother. They’re going to bring her up.”41

Though Washington was well liked as a person, Bill North—a first-rate base-stealer—turned out to be his best friend on the club. They got adjoining rooms on the road. As Herb told Leonard Koppett of the New York Times, “He was open with me. He told me he didn’t like the job I was given to do, but that he liked me—and he’s helped me as much as he can all along.”42 Vida Blue was also a comrade.

Washington pinch-ran twice in the AL Championship Series against Baltimore. Both times he was caught stealing, first by Elrod Hendricks in Game Two (the A’s were up 2-0 but then added three more runs) and then by Andy Etchebarren in Game Three (the A’s led 1-0 and that was how it ended).

The focal point of Washington’s baseball career came in Game Two of the 1974 World Series at Dodger Stadium. Alas, it was a mistake. Dodgers starter Don Sutton took a 3-0 lead into the ninth inning, but he hit Bando with a pitch and gave up a double to Jackson. Iron man reliever Mike Marshall relieved Sutton, and Rudi then singled to cut the lead to one run. Rather than sacrifice, Dark left Rudi in while power-hitting Tenace was up, but after Tenace struck out, Washington came on.

Marshall was known for his pickoff move, which was self-developed, unorthodox—and highly effective. Vin Scully, calling the game for NBC, said, “Marshall, for a right-hander, is very quick in coming over to first base.” Being the Dodgers broadcaster, Scully had seen it often.

The first pitch to Ángel Mangual, batting for Blue Moon Odom, was a strike. Marshall made one soft toss over to first. He then stepped off the rubber three times, feinted once, but didn’t throw. In 1988, Charlie Finley said, “I remember telling the person I was with that Marshall was playing possum. … Don’t be surprised if he picks him off.”43 Sure enough, Marshall whipped a sudden throw over and caught Washington leaning the wrong way. Scully said, “He really set him up. … He is hung out to dry.” Steve Garvey applied the tag. By coincidence, both Garvey and Marshall were also MSU Spartans.

Washington pounded the ground and said, “Damn.” Said Finley, “If I’d had a lever that would have dropped me out of the stadium, I’d have pulled it. I felt as if the whole world was looking at me and laughing.”44 With the wind out of Oakland’s sails, Mangual then struck out on two more pitches, and the Dodgers got their only win of the Series. “I had never seen [Washington] on the basepaths until today,” said Marshall. “I was his teacher. He was my student. I taught him child growth and development.”45 The pitcher wasn’t drawing a condescending analogy—that was in fact their relationship while Washington was studying education at Michigan State.

Despite Washington’s tenuous position among his teammates, none of them came down on him for the faux pas. Even Tenace, who had been critical of the roster choice early on, said, “He’s a tremendous person, and he has done a tremendous job for us. I’ll say this about him, he adjusted. … You have to give him credit for that. I know I do. I really like the guy. He made up his mind it didn’t matter to him what people thought, he was going to do his job, and he did.” Dark also gave a supportive pat on the butt, and Jackson took the time to sit down next to Washington for a little pep talk on the bus ride from Dodger Stadium to the airport.46

Washington’s confidence was not damaged; he said that the Dodgers would hear from him before it was over. It didn’t quite work out that way, but he did at least get to appear in two more World Series games. He came on for Tenace in the eighth inning of Game Three, with the A’s up 3-2 and seeking an insurance run, but he remained at first as the next two batters both made outs. Then in Game Four, after Jim Holt’s pinch double capped Oakland’s winning four-run rally in the sixth inning, Washington replaced Holt—but was immediately forced out at second.

After the A’s polished off the Dodgers, Washington participated fully in the celebration. One wire-service photo showed him with upturned face as pitcher Darold Knowles sat atop the lockers and poured down champagne. He got a full Series share of $22,210, but later pointed out, “They didn’t have a say. If you were there for the full season, it was automatic. I was one of the voters.” He remembered some ribbing about what might have happened if he’d been there just part of the time.47

During the following offseason, Washington ran with the International Track Association. He found training for baseball easier than the regimen for track—but he also admitted, “You don’t have to be fast to steal [bases]. There are two things more important than speed. One is knowledge of the pitcher and the other is the jump you get. Put them together and you compensate for the speed factor.”48

In his second year, Washington was looking forward to developing and applying these skills further.49 Near the end of spring training in 1975, however, the A’s bought the contract of minor-league outfielder Don Hopkins from the Montreal Expos. Hopkins was another speedster from Michigan. In fact, he once ran the 100-yard dash against Washington in 1969 and finished second (his time was 9.5 seconds, 0.2 behind Washington).50 Hopkins had stolen a lot of bases—224 in 340 minor-league games from 1970 through 1974—but hit just .249 with no homers and few extra bases. Still, he was a pro ballplayer—although Oakland released veteran outfielder Jesús Alou to make room for “Hoppy.”

Charlie Finley proclaimed, “We’re going to keep both [Hopkins and Washington]. These two pinch-runners are going to help us as our 24th and 25th players. … We used to pitch teams to death and now we’re going to run and hit them to death.” Dark toed the company line, though Bando shook his head in disbelief. Finley’s sarcastic response was, “I don’t know what the manager’s committee will say. You know, the players on the team who think they run the club.”51

“I questioned it,” Washington said of the Hopkins deal. “Then I said maybe we can.”52 But then, on April 28, Oakland also acquired Matt Alexander in a minor-league deal with the Chicago Cubs. Alexander was another very speedy man who could play both the infield and the outfield, plus he wasn’t a bad hitter. Reggie Jackson said, “We’ve got these two new guys—Alexander and Hopkins—and they can do other things, plus they run the bases better than Washington.”53

“When they got Matt Alexander,” said Washington, “there was no way. Not three runners.”54 Actually, the trio did play together briefly—all were used in extra-innings games on May 2 and 3. Herb made his 13th and final appearance of 1975 on May 4. The next day he was released (Finley gave him the news in person). “I’d feel sorry for him if he were a player,” said Sal Bando, with no malice intended.55

“We hate to give him up,” said Finley, “but we have to because, for one thing, the pennant race is a lot tighter this year. We’ve got to have pinch-runners who can steal bases and also do some other things.” The loss of Catfish Hunter to free agency was also a factor, according to Finley. Washington later explained, “He (Finley) said they might have to carry another pitcher. He didn’t think I’d get the kind of experience I needed in the minors.”56

“I’m not really upset about it,” said Washington. “I would have been really disappointed and disillusioned if I didn’t expect it. But I still didn’t think it would be me when it came to the choice of the three, even though Alexander and Hopkins both can play other positions. I thought that because of what I did last year and how much I learned that I could be a greater asset this year.” He added, “This isn’t my biggest disappointment. That was when I didn’t make the Olympics in 1972.”57

Finley suggested the possibility that Washington could return late in the 1975 season or in 1976, and Herb believed him.58 Meanwhile, he planned to get into the food business and to run in professional track events.59 As it developed, however, Oakland used Hopkins in 82 games in 1975 and Alexander (who missed some time with a broken eye socket) in 63. There still simply wasn’t room for Washington.

As late as February 1976, A’s beat writer Ron Bergman reported that according to Finley, Washington had phoned a couple of times, but the owner said that Herb would not be with the A’s that season.60 According to Washington, though, “I knew it was over. Once I was gone, I was gone.”61

Indeed, in October 1975 Oakland had acquired yet another man who would be used largely as a pinch-runner: Larry Lintz, a second baseman by trade. Lintz spent most of 1976 and ’77 with the big club, along with Alexander. Hopkins made just three more big-league appearances, in September and October 1976. The A’s kept Alexander (whom his teammates regarded as the most complete player of the lot) on the roster for all of 1976 and 1977, but released him at the end of March 1978. Lintz was cut right around the same time.

It’s not entirely clear why Finley, in his capacity as general manager, became disenchanted with pinch-running specialists. He did use one more, though: Darrell Woodard, a second baseman who came up in the A’s chain at the same time as the all-time king of stolen bases, Rickey Henderson. Woodard got into 33 games from August through October 1978, of which 22 were just as a pinch-runner.

Washington did rejoin the International Track Association in 1975 and came back once more in 1976, but the tour did not complete its final season. After that, he focused on his career with McDonald’s, which had started when he got his first franchise in Detroit in the summer of 1975.62 In 1980 Washington moved from Detroit to Rochester, New York, where he built up a chain of Golden Arches. In 1993, he said, “When I visited Rochester in 1980, I thought, it looks like there are a lot of burger eaters here.”63

Washington’s success in the area won him additional honor. In July 1990 the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System appointed him as a director of the Buffalo branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.64 In January 1992 he was named chairman of the Board of Directors of that institution.

Washington left Rochester in May 1998 to buy 19 McDonald’s restaurants in the Youngstown, Ohio, area. He said, “It was about opportunity for really significant growth—nothing else. The city [Rochester] has been great. We’ve enjoyed it here. But the opportunity is such that when it comes, you have to be ready to seize it.”65

H.L.W. Fast Track continued its robust growth. It was ranked at number 56 on the 2012 Black Enterprise “Top 100”—a list of the largest companies in America owned by African-Americans.66 As of early 2012, the company owned 25 McDonald’s outlets in a territory spanning from Cleveland to western Pennsylvania. Total employment was about 1,500. Terrell Washington was working with his father as general manager.67 His sister, Ari, also became an entrepreneur, starting her own boutique public-relations firm in 2010.

Washington also got involved with a different sport—ice hockey. In 2005 the Youngstown SteelHounds joined the Central Hockey League, and Herb was the club’s owner. The SteelHounds played three seasons before the CHL terminated the franchise’s membership in 2008 amid an ongoing financial dispute.

Michigan State University inducted Herb Washington into its Athletics Hall of Fame in 2000. In September 2010 Herb and his wife, Gisele, made a gift of $250,000 to their alma mater, establishing a scholarship for deserving MSU students who participate in men’s varsity track and field. They also designated part of their gift to support the men’s track program. Previously, in 2009, Washington had donated $20,000 to an effort to build a new track for Flint’s Northwestern High School. He’d given up sprinting, but he still ran four miles about three times a week.68

Four decades after Washington ran the basepaths for Oakland, his name still cropped up frequently in baseball discussions. One prominent example came in September 2013, when the Cincinnati Reds called up Billy Hamilton for the first time. Hamilton, a man with blazing speed, had stolen 395 bases in five seasons in the minors, including an astonishing 155 in 2012. Among many articles that name-checked Washington, the Wall Street Journal ran one called “Billy Hamilton: The Reds’ Designated Runner.” Hamilton, however, came up through the minors as a true center fielder, and the Reds did not limit him solely to the specialty role. Cincinnati manager Dusty Baker said, “He’s not going to be Herb Washington. … He’s going to be Herb Washington sometimes.”69 In a curious twist, Ari Washington became Hamilton’s PR representative.

Herb never had to face a pro curveball, but looking back in 2002, he talked confidently about what might have been. “I felt like if I had spent the time in baseball that I did in track, I could have played. I just had not done the kind of training that was necessary to participate at that level.”70 Yet before that, he took a different tack. Recalling that Alvin Dark offered him a chance to pinch-hit after Oakland had clinched the division in 1974, Washington said, “Something suddenly dawned on me. … If I were to get an at-bat, I’d be just like every other major leaguer. So I turned Alvin down. If I hadn’t, I’d have lost my significance.”71

Reminiscing again in 2014, Washington said, “I was fortunate enough to be on a team with some really talented guys and some good guys. It made me grow up! You gotta depend on yourself as a sprinter, and that was reinforced on the A’s.”72

Sources

Grateful acknowledgment to Herb Washington for his memories (telephone interview, January 6, 2014).

Warren, Peter, “Designated Runner: Herb Washington,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Fall 2011.

Blau, Clifford, “Leg Men,” Baseball Research Journal, Society for American Baseball Research, Summer 2009.

baseball-reference.com

retrosheet.org

msuspartans.com (Michigan State football statistics)

fpl.info/hallfame/99/washington99.shtml (Flint Public Library—Greater Flint Afro-American Hall of Fame)

msuba-det.org (Michigan State University Black Alumni website)

www.findagrave.com

Notes

1 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

2 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

3 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

4 “Herb Washington: World-Record Sprinter & Business Success,” MSUSpartans.com, February 19, 2007 (msuspartans.com/genrel/021907aac.html)

5 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

6 Bill Halls, “Washington, Wallace Duel Highlights State Track Meets,” Associated Press, May 24, 1968.

7 “Schoolboy Sets World 50-Yard Mark,” Associated Press, March 25, 1968. It was unofficial because the International Amateur Athletic Federation did not recognize indoor marks.

8 Joe Scalzo, “Former A’s pinch runner pinch-hits for area coaches,” The Vindicator (Youngstown, Ohio), March 16, 2004, C3.

9 Adrianna Mondore, “One of a Kind,” National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum website, February 11, 2013 (baseballhall.org/news/personality/one-kind)

10 “Herb Washington, World-Record Sprinter & Business Success”, MSUSpartans.com, February 19, 2007 (msuspartans.com/genrel/021907aac.html)

11 “Mich. State Greens Rout Whites, 58-13,” Chicago Tribune, September 14, 1969.

12 Bob Voges, “Good Test in Store for Spartans,” Associated Press, September 16, 1969.

13 “MSU Sprinter Washington Quits Football,” Chicago Tribune, October 21, 1970, C5. One of MSU’s starting wide receivers, Gordon Bowdell, had a brief career in the NFL. However, the most successful pass catcher on that team turned out to be tight end Billy Joe DuPree, who played for the Dallas Cowboys from 1973 through 1983.

14 “Carlos Loses Dash at Midwest Meet,” New York Times, February 14, 1970.

15 “Washington Buzzes 5.1, Ties Record,” Associated Press, March 23, 1970.

16 Sandi Genis, “Washington ties sprint record,” The Michigan Daily (Ann Arbor, Michigan), February 14, 1971, 9.

17 Bert Rosenthal, “Herb Washington, On Way to an Olympic Spot, Hopes to Do as Well with the Colts,” Associated Press, February 19, 1972.

18 “Patty Johnson Breaks Record,” Associated Press, February 6, 1972.

19 “Spartan Sets World Mark,” Associated Press, February 14, 1972.

20 In Munich that August, Rey Robinson and Eddie Hart—the leading American candidates to win a gold medal in the 100-meter dash—were disqualified because the US sprint coach gave them the wrong time for their quarterfinal heat.

21 Kenny Moore, “Eff Ell Wyeing on the Bases,” Sports Illustrated, June 10, 1974.

22 “Colts open pre-season camp in Tampa July 19,” Baltimore Sun, July 6, 1972, D5. James H. Jackson, “Sprinter to decide on Colt offer,” Baltimore Sun, July 9, 1972, B8. Cameron C. Snyder, “Thomas seeks Colt trades,” Baltimore Sun, July 19, 1972, C1. Fred Girard, “ ‘Tampa Dew’ Welcomes Colts,” St. Petersburg Times, July 20, 1972, 1-C.

23 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

24 “Washington Keeps Sprint String Intact,” Associated Press, January 29, 1974.

25 “Washington Keeps Sprint String Intact.”

26 “I.T.A. Lists ’75 Schedule of 17 Meets,” New York Times, November 20, 1974. This article announced the signing of Washington. Wire service reports from January 12, 1975 also described Washington as “a new face” for the ITA.

27 “Sprint ace wants pro grid career,” United Press International, February 23, 1974.

28 Ron Bergman, “Finley’s Speed-to-Burn Plan Gives Athletics Sudden Chill,” The Sporting News, April 6, 1974, 18.

29 “Herb Washington: World-Record Sprinter & Business Success.”

30 “Finley Signs Washington as Pinch-Runner for A’s,” The Sporting News, March 30, 1974, 48.

31 “Herb Washington Waiting for Finley’s Decision,” Newspaper Enterprise Association, January 2, 1975.

32 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

33 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

34 Moore, “Eff Ell Wyeing on the Bases.”

35 “From basepaths to the cinders,” Associated Press, November 20, 1974.

36 “Herb Washington Plans More Thefts,” Associated Press, March 18, 1975.

37 Eric Prewitt, “Herb Washington Has Lot to Learn,” Associated Press, April 19, 1974.

38 “Herb Washington Waiting for Finley’s Decision.”

39 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

40 Eric Prewitt, “Herb Washington on Waivers,” Associated Press, May 6, 1975.

41 Jorge L. Ortiz, “Where Are They Now? Herb Washington,” San Francisco Chronicle, January 13, 2002. Scalzo, “Former A’s pinch runner pinch-hits for area coaches.”

42 Leonard Koppett, “The Herb Washington Experiment,” New York Times, August 25, 1974.

43 Ross Newhan, “The World Series: Athletics vs. Dodgers,” Los Angeles Times, October 14, 1988.

44 Ibid.

45 Ian MacDonald, “Marshall teaches Washington lesson,” Montreal Gazette, October 15, 1974, 18.

46 Milton Richman, “Herb Washington says LA will hear from him,” United Press International, October 15, 1974.

47 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

48 “From basepaths to the cinders.”

49 “Herb Washington Plans More Thefts,” Associated Press, March 18, 1975.

50 Ron Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy,” The Sporting News, April 19, 1975, 5.

51 Bergman, “Happy Charlie Does Jig Over Hippity-Hoppy.”

52 “A’s Cut Herb Washington; Roger Nelson Joins Club,” United Press International, May 6, 1975.

53 Ron Bergman, “Loss of Catfish Hastened Herbie’s Farewell,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1975, 13.

54 “A’s Cut Herb Washington; Roger Nelson Joins Club.”

55 Eric Prewitt, “Herb Washington on Waivers,” Associated Press, May 6, 1975

56 “Washington Eyes Return,” Associated Press, June 13, 1975.

57 “A’s Cut Herb Washington; Roger Nelson Joins Club.” “Pinch Runner Washington Given Release by Champs,” Associated Press, May 6, 1975.

58 “Washington Eyes Return.”

59 Bergman, “Loss of Catfish Hastened Herbie’s Farewell,” The Sporting News, May 24, 1975, 16.

60 Ron Bergman, “Finley Buries All Rumors of A’s Departure,” The Sporting News, February 14, 1976.

61 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

62 Peter Gammons, “Pro Baseball,” Boston Globe, June 15, 1975.

63 Franz Lidz, “Whatever Happened To…: Herb Washington,” Sports Illustrated, July 19, 1993.

64 “Rochester Businessman Named Fed Bank Director,” Buffalo News, July 21, 1990.

65 Mike F. Molaire, African American Who’s Who, Past & Present, Greater Rochester Area, Rochester (New York: Norex Publications, 1998), 194.

66 “Black-owned businesses,” The Vindicator, July 7, 2012.

67 George Nelson, “McDonald’s Operator Plans Big Upgrades,” The Business Journal (Youngstown, Ohio), February 3, 2012.

68 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

69 Owen Perkins, “Reds expect light September role for Hamilton,” MLB.com, August 31, 2013.

70 Ortiz, “Where Are They Now? Herb Washington.”

71 Lidz, “Whatever Happened To … Herb Washington”. According to the article, Nolan Ryan was the opposing pitcher, but the record shows that Frank Tanana and Chuck Dobson pitched the last two games for California.

72 Telephone interview, Rory Costello with Herb Washington, January 6, 2014.

Full Name

Herbert Lee Washington

Born

November 16, 1951 at Belzoni, MS (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.