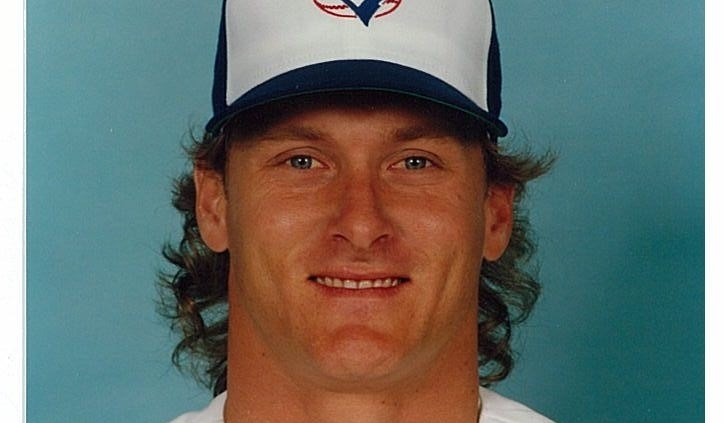

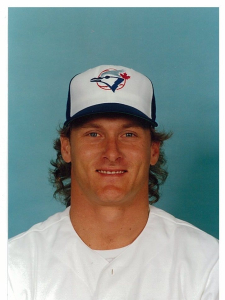

Kelly Gruber

“Gruber plays baseball the way paying customers expect to see a guy play baseball – at full speed. He runs hard. He crashes into things. He never met a takeout slide he didn’t like. He dives for balls, spending a measurable portion of each game at third base down on the ground. If he isn’t dirty by the fourth inning, he thinks he’s not earning his money.” — Dave Perkins, The Sporting News1

Kelly Wayne Gruber was born on February 26, 1962, in Houston, Texas. His family name at birth was King, for his biological father was Claude King, a professional football player during the 1960s. His mother, Gloria (Hunt) King, won the 1957 Miss Texas pageant2 and was part of a singing trio whose accomplishments included performing opening acts for Elvis Presley.3 Soon after Kelly was born, Claude abandoned the family, leaving Gloria to care for Kelly and his older sister, Claudia. Gloria found work as an administrative assistant. She later married real estate executive David Gruber, who adopted Claudia and Kelly in October 1966.4 Gloria and David welcomed a third child, David Jr., born in 1967.5

Kelly Wayne Gruber was born on February 26, 1962, in Houston, Texas. His family name at birth was King, for his biological father was Claude King, a professional football player during the 1960s. His mother, Gloria (Hunt) King, won the 1957 Miss Texas pageant2 and was part of a singing trio whose accomplishments included performing opening acts for Elvis Presley.3 Soon after Kelly was born, Claude abandoned the family, leaving Gloria to care for Kelly and his older sister, Claudia. Gloria found work as an administrative assistant. She later married real estate executive David Gruber, who adopted Claudia and Kelly in October 1966.4 Gloria and David welcomed a third child, David Jr., born in 1967.5

As a child, Gruber had a very close relationship with his maternal grandparents, Vita and Archie Hunt. While they played an important emotional role during Kelly’s early years, their lack of discipline meant that he was ill prepared for the strict domestic structure that arose once David Sr. entered his life. David frequently chose whipping as the form of punishment, which he later regretted.6 For his part, Kelly acknowledged that at times he never met his stepfather halfway where behavior was concerned. “I wasn’t the son I should have been, because I thought David Sr. might leave me, too,” he said. “I rebelled because of it. I think that’s why I was so close to my grandparents. I was sure of them. I knew they would never leave me.”7

Gruber was a gifted varsity athlete, playing football, baseball, basketball, and athletics at Westlake High School in Austin. His baseball coach, Howard Bushong, observed that Gruber performed best at baseball and never lacked self-confidence, telling a sportswriter, “He was a go-getter, but backed up that attitude.”8 Gruber played three seasons as the starting shortstop for the Westlake Chapparals, where he earned All-American honors and won the state championship in 1980.9

Gruber’s final year of high school proved to be the turning point of his athletic career. Not only was he offered a four-year scholarship from the University of Texas for either baseball or football,10 the Cleveland Indians selected him 10th overall in the June amateur draft, the day before the state semifinals. This led to confusing emotions for Gruber. “For a young buck my age, it wasn’t easy keeping my mind straight,” he said.11 In the end he decided to forgo college and signed with Cleveland for a $100,000 bonus paid in two installments.12 In later years Gruber expressed no regrets with his decision: “I didn’t care much about baseball. … But I picked it; it had the better opportunity for a long career. And the bonus money was real good.”13

Soon after signing his first professional contract, Gruber reported to Batavia of the New York-Pennsylvania League, Cleveland’s short-season Class-A affiliate. Confident in his talent and abilities, he initially expected a short stay. “It wasn’t necessary as far as I was concerned,” he told his biographer.14 His play, however, did not match his confidence. In 61 games he batted .217 and made 21 errors at shortstop. Despite the lackluster debut, his fielding coach, Luis Isaac, noticed that Gruber might not have been playing the most optimal position for his skill set. “The errors he was making, it was because he was too quick to the ball,” Isaac said. “… In my reports to the big club, I would put that he was more suited to be at third.”15

Gruber showed promise the next year with the Waterloo Indians of the Class-A Midwest League, making 500 plate appearances, the most of his minor-league career. He hit .290 with 14 home runs and 59 RBIs. In the field, however, Gruber’s defense continued to waver; he made 56 errors at shortstop and had a .910 fielding percentage.

After a stint of winter ball in Venezuela, Gruber began the 1982 season with Chattanooga of the Double-A Southern League. It was here that Gruber’s confidence and defensive performance reached an all-time low. On April 15 vs. the Birmingham Barons, he made five errors in a game, a league record at shortstop. “I wanted to dig a hole at shortstop and crawl into it. … I should’ve accepted what happened and put it behind me. … Instead, I let it bother me for the rest of the season,” he told his biographer.16 His offensive numbers declined in nearly all categories from the previous season.

Gruber continued in Double A in 1983, as a member of the Buffalo Bisons. The change of scenery did not improve his caliber of play. Further complicating matters was a sour relationship between Gruber and his manager, Al Gallagher. Gallagher moved Gruber from shortstop to third base after the fifth game of the season, finally carrying out a move first advocated by Luis Isaac in Batavia three years earlier. However, convinced that Gruber would never reach his full potential, Gallagher informed Cleveland’s front office that it was time to move on from the Gruber experiment.17

After a disappointing season in Buffalo, Gruber headed to Colombia for another season of winter ball. Meanwhile, events were transpiring that would lead to his departure from the Cleveland organization. In November, Indians general manager Phil Seghi phoned his counterpart in Toronto, Pat Gillick, to ask if Gillick wouldn’t mind reviewing the scouting reports on Gruber. Coincidentally, Gillick received a call a few days later from Duane Larson, the Blue Jays’ scout in Colombia, informing him of Gruber’s impressive performance. Recognizing that an opportunity might be in the works, Gillick sent two senior scouts, Bobby Mattick and Al LaMacchia, to Colombia to watch Gruber. They agreed with Larson’s assessment, prompting Gillick to select Gruber in the subsequent Rule 5 draft.18

Colombia winter ball was not the first time the Blue Jays took notice of Gruber, however. In 1979 Al LaMacchia had gone to Austin to scout one of Gruber’s teammates, pitcher Calvin Schiraldi. It didn’t take long for Gruber to make an impression on the veteran scout.19 LaMacchia returned the next summer for a private workout with Gruber, which only helped to reinforce his belief in the young Texan. Despite a strong interest, the Jays chose infielder Gary Harris, who would toil in the minors for three years before retiring from baseball. This selection left Gruber available for Cleveland, which selected him with its first pick. Years later LaMacchia lamented the Jays’ decision to select Harris over Gruber by concluding, “We made a tremendous mistake.”20

Gruber made the Blue Jays’ Opening Day roster in 1984, primarily because his Rule 5 status meant the Blue Jays would have to keep him on the major-league roster or return him to Cleveland.21 He made his major-league debut on April 20,1984, as a defensive replacement in the 12th inning at Exhibition Stadium against the California Angels, recording one assist in a 10-6 loss. Gruber saw little game action and in May was sent to Triple-A Syracuse for regular playing time. (In exchange for not returning Gruber to the Indians, Toronto sent Cleveland catching prospect Geno Petralli.) The season ended on a memorable note for Gruber: After he returned to the Blue Jays as a September call-up, his first hit was a two-run, pinch-hit home run in the ninth inning of a blowout loss to the Red Sox on September 25. He received a standing ovation from the Fenway Park faithful, along with chants of “Groo-bah! Groo-bah!,” prompting teammates to shove Gruber to the top step of the dugout for his first big-league curtain call.22

Gruber played in only five games with the Blue Jays in 1985, all after call-up time. He was maturing in his outlook and sought to take full advantage of an opportunity to play full time for Syracuse. “The Blue Jays told me they thought I had a shot (at making their 25-man regular-season roster). But, inside, I personally didn’t think I was ready. I knew I needed another year at Syracuse.”23 He hit 21 home runs and had 69 RBIs in 121 games, and was named the International League’s all-star third baseman.

Gruber spent the entire 1986 season with the Blue Jays, playing 87 games, 42 at third base, with the remaining appearances at second base, shortstop, and each outfield position. He received high praise from manager Jimy Williams: “We feel Gruber can do an excellent job at a number of positions. He can go in without weakening us in any way, shape or form.”24 He had 28 hits in 152 plate appearances, perhaps none more memorable than his only major-league inside-the-park home run, on June 12 against the Detroit Tigers. By the seventh inning of the night game, dense fog had crept in from Lake Ontario over Exhibition Stadium when Gruber stepped in the box to face reliever Bill Scherrer with two on and two out. He hit a “very catchable” fly ball that bounced about 30 feet to the left of the center fielder. Gruber scored easily on the play, breaking a 0-for-27 slump.25

Gruber entered the 1987 season with high expectations. “I know 20 home runs is possible, and, for sure, I want to bag as many stolen bases,” he told a sportswriter. “… I like the first pitch a lot. I don’t want to go up there surveying balls and strikes; I want to be hacking.”26 His intense style of play made him injury prone, leading to missed games as a result of rib, ankle, and foot issues. His aggressiveness and frequent injuries led to criticism from some of his teammates, much to Gruber’s ire. “Some guys on the team have even had the nerve to tell me to stop diving for balls. But that’s not my game,” he said. “I play hard, aggressive; that’s the only way I know how to play.”27 This aggressive style of play and the injuries that followed, along with the ensuing criticism from teammates, media, and fans would return to beleaguer Gruber later in his career. He finished the season with 12 home runs and 12 stolen bases in 138 games.

The next year Gruber began to round into major-league form. He learned in spring training that he’d be the backup third baseman to Rance Mulliniks. These plans changed during the first inning of the home opener on April 11 against the Yankees, when Rickey Henderson slid head-first into Mulliniks’s knee while stealing third base.28 Gruber replaced Mulliniks and ended up starting at third for 148 of the Jays’ remaining 155 games.29 Aside from regular playing time, a major factor for his emerging success was the tutelage from Blue Jays hitting coach Cito Gaston. Of his student, Gaston noted, “Kelly’s got a better idea of what he wants to do up there now. … You can’t just go up there and hack away; you’ve got to have a plan.”30 The 1988 campaign turned out to be one of Gruber’s best offensive seasons, as he finished with a .278 batting average and a .328 on-base percentage, along with 16 home runs and 81 RBIs.

The 1989 season provided a snapshot of how potent a player Gruber could be when he stayed healthy. GM Pat Gillick proclaimed Gruber one of his “untouchable” players in spring training, stating, “He’s got more talent and all-round ability than any guy we’ve got.”31 On April 16 at home vs. the Kansas City Royals, Gruber made history by becoming the first Blue Jay to hit for the cycle. Gruber’s impressive performance continued, leading to him being selected for the All-Star Game by American League manager Tony LaRussa. While he did not see game action, the confidence Gruber gained helped to sustain his play for the rest of the season, resulting in the Elias Sports Bureau ranking him the top third baseman in the American League.32 His popularity soared among Blue Jays fans, who voted him Toronto’s favorite athlete in an annual survey of readers of the Toronto Star. 33

After a disappointing loss to the Oakland Athletics in the 1989 ALCS, the Blue Jays envisaged greater things for 1990. Gruber did his part by remaining relatively healthy and posting the best numbers of his career. He batted .274 with 31 home runs and 118 RBIs, earning an AL Silver Slugger Award. In the field he won his only AL Gold Glove Award. Gruber again was chosen for the All-Star Game and stole two bases, tying Willie Mays for the most stolen bases in the midsummer classic. By the end of the regular season, he earned fourth place in voting for the AL MVP Award, and was the unanimous choice as player of the year by the Toronto chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America.34 Gruber’s play could not help his team reach the playoffs: The Blue Jays finished two games behind the Red Sox for the AL East title.

In February 1991 the Blue Jays rewarded Gruber with a three-year, $11 million contract, which at the time made him the highest-paid Toronto sports athlete and major-league third baseman.35

Gruber’s success was short-lived, however, as injuries led to a rapid fall from grace. He tore several ligaments and suffered a fracture of his right thumb while running the bases against the Texas Rangers on May 1, 1991.36 The injury affected him for the rest of the season and limited him to 113 games. His inability to return to action caused teammates to question his commitment, calling him “Mrs. Gruber” behind his back.37 This proved to be a far cry from the applause and accolades Gruber had seen the previous two seasons. After a disappointing playoff exit at the hands of the Minnesota Twins, many fans and the media thought Gruber should be dealt. As he had for many years, GM Pat Gillick remained committed to his third baseman, saying, “Everybody’s tradeable, but we’re not going to trade Kelly Gruber.”38

Gruber’s hand injury healed in the offseason and he began the 1992 season with hopes of 100 or more RBIs.39 But he soon suffered an injury that eventually ended his major-league career. In his first at-bat of a game on April 26 vs. Kansas City, he swung through a pitch and “felt something pop.”40 The injury turned out to be a bone spur embedded in his spinal cord,41 and was not properly diagnosed until 1995.42 Gruber continued to play through the pain but performed nowhere near expectations. He hit 11 home runs, drove in 43 runs, and batted .229. The man who was voted Toronto’s favorite athlete two years earlier was now vilified as being lazy by an increasing number of the Blue Jays’ fan base.

Despite his injuries and inconsistent play, Gruber displayed flashes of his former self during the 1992 postseason. In Game Two of the ALCS against Oakland, he hit a two-run homer in the bottom of the fifth inning to break a scoreless tie, helping the Blue Jays win 3-1.

Five years earlier, in spring training, Gruber had told of his desire to play in the World Series as a Blue Jay. “I got a chance of a lifetime here to go to a World Series. People talk about how someone like Tony Kubek got there seven times or something and that’s fine but, hey, just give it to me once.”43 Gruber’s wish would come true, and it was in Game Three that he had his best performance. In the top of the fourth inning, Devon White made an incredible catch against the center-field wall, leading to chaos on the basepaths. In the confusion, Terry Pendleton crossed Deion Sanders at second base, leading to the second out. The ball then found its way to Gruber, who ran a stranded Sanders back to second, where Gruber dived and tagged Sanders on his right heel for what should have been the third out and a triple play. The second-base umpire disagreed, calling Sanders safe. While diving to tag Sanders, however, Gruber tore his rotator cuff. Despite the injury, Gruber continued to play, and in the top of the eighth inning, he made an error when he couldn’t hold on to a line drive off the bat of Otis Nixon, who later scored and gave Atlanta a 2-1 lead. When Gruber led off the bottom of the inning, boos echoed through SkyDome. Despite feeling incredible pain and unable to hold up his bat with his left hand, he hit a changeup off Steve Avery for a home run to tie the game. The jeers quickly turned to cheers and Gruber was once again a hero. “It was the only pitch … I could get that bat around (on),” he said later “… Going around those bases, finally, it was like, ‘Wow. Well, at least I could do one good thing this series.’”44

Gruber’s time with the Blue Jays was over. Shortly after Toronto’s first World Series championship, Gruber was traded to the California Angels for Luis Sojo. Toronto agreed to pay $1.5 million of Gruber’s $4 million salary in 1993 as part of the agreement.45 While undergoing his medical in early 1993, Gruber was officially diagnosed with a torn rotator cuff and underwent surgery. He did not play until June 4, prompting the Angels to complain to American League President Bobby Brown that the Blue Jays had knowingly dealt them an injured Gruber. Brown’s investigation concluded that Toronto was unaware of the severity of Gruber’s injury and declared the matter closed.46 Gruber played in 18 games for the Angels before heading to the disabled list on July 4 with recurring neck issues. He was placed on waivers on September 7 and subsequently released.47

Neck issues continued to keep Gruber away from baseball, ultimately leading to surgery in August 1995 to fuse a bone from his hip into his neck.48 After his recovery, he signed a minor-league deal in late 1996 with the Baltimore Orioles, who were now under the guidance of Pat Gillick. Gruber was the final cut at the end of spring training and began the 1997 season with the Triple-A Rochester Americans. He played in 38 games for Rochester before suffering a strained hip flexor. After his rehab failed to sufficiently allow him to return to game shape, he determined that his playing career was over and retired.49

Gruber has remained active within Canadian baseball circles in his retirement. He has appeared in numerous charity events for the Jays Care Foundation and participated in several Blue Jays alumni events. He also traveled extensively throughout Canada hosting his Kelly Gruber Silver Slugger baseball camps for children aged 9 to 17. He made headlines in 2018 for two alcohol-related incidents, the first of which included an arrest in April in Austin, Texas, for driving under the influence.50 The second incident occurred in June during a fan event at the Canadian Baseball Hall of Fame’s annual induction weekend, when he made inappropriate remarks toward host Ashley Docking and fellow guest Kevin Barker.51 Organizers, suspecting Gruber was inebriated, quickly ended the panel, and Hall of Fame organizers disinvited him from the weekend’s remaining events.52

Gruber married Toronto native Lynn Seguin in 1986. They have two children, Kody and Cassie. The couple divorced in 1993.53 While playing with the Angels, he met his second wife, Tosca. They reside in Texas with their three children, Samantha (from Tosca’s first marriage), Kyle, and Kolton.54

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball Reference, Retrosheet, and the Kelly Gruber Hall of Fame media file.

Notes

1 Dave Perkins, “Blue Jays’ Fearless Kelly Gruber Is an All-Star at Third Base, a Heartthrob in Toronto,” The Sporting News 1991 Baseball Yearbook: 34.

2 Miss Texas USA, “Hall of Fame: Miss Texas USA,” https://www.misstexasusa.com/halloffame-miss/, accessed December 3, 2021.

3 Barry Davis, “Kelly Gruber: Outta the Park with Barry Davis,” January 17, 2020, https://soundcloud.com/user-250213153/otp-kelly-gruber-jan-17, (accessed December 3, 2021).

4 Kevin Boland and Kelly Gruber, Kelly: At Home on Third (Toronto: Viking, 1991), 4-5, 251.

5 Rick Cantu, “Westlake’s State Championship Seasons Provide Special Memories for Gruber Brothers,” Austin American-Statesman, June 12, 2013, https://www.statesman.com/story/news/2013/06/12/westlakes-state-championship-seasons-provide-special-memories-for-gruber-brothers/9989001007/, (accessed December 3, 2021).

6 Boland and Gruber, 5-6.

7 Boland and Gruber, 6.

8 Dick Clarke, “Jays Glad Gruber Did Not Choose Football,” Syracuse Herald Journal, August 19, 1990: 10.

9 Thomas Jones, “50 Years of Westlake Athletics: The Chaps’ All-Time Baseball Team,” Austin American-Statesman, June 30, 2020, https://www.statesman.com/story/sports/high-school/2020/06/30/50-years-of-westlake-athletics-chaps-all-time-baseball-team/113718960/, (accessed December 3, 2021).

10 Boland and Gruber, 28.

11 Cantu, “Westlake’s State Championship Seasons Provide Special Memories for Gruber Brothers.”

12 Boland and Gruber, 38.

13 Clarke, “Jays Glad Gruber Did Not Choose Football.”

14 Boland and Gruber, 42.

15 Boland and Gruber, 42.

16 Boland and Gruber, 48-49.

17 Boland and Gruber, 60.

18 Milt Dunnell, “Gillick Was Asked: ‘Is Kelly Gruber Worth $100,000?,” Toronto Star, February 17, 1991: G4; Kristina Rutherford, “The Interview: Kelly Gruber on Pablo Escobar, ADHD, and the ’92 World Series,” https://www.sportsnet.ca/baseball/mlb/interview-kelly-gruber-pablo-escobar-adhd-92-world-series/, (accessed November 18, 2021).

19 Boland and Gruber, 21.

20 Boland and Gruber, 25.

21 GruberBaseball.com, “About Kelly,” https://web.archive.org/web/20111019201914/http://gruberbaseball.com/about-kelly/, (accessed December 3, 2021).

22 Paul Patton, “Stieb Roughed Up as Bosox Breeze to an Easy Victory,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), September 26, 1984: S3.

23 Garth Woolsey, “Kelly Gruber Certain He’s Made Jays,” Toronto Star, April 1, 1986: E1.

24 Jim Proudfoot, “Gruber’s Versatility Gives Jays Added Dimension,” Toronto Star, March 21, 1986: F1.

25 Allan Ryan, “Game Called After Seven – Key Gets Shutout Win,” Toronto Star, June 13, 1986: B1.

26 Allan Ryan, “Afternoon of Good News for Gruber,” Toronto Star, March 30, 1987: D4.

27 Dave Perkins, “Gruber Can’t Shake Injuries,” Toronto Star, April 29, 1987: C2.

28 Dave Perkins, “Mulliniks Gets Word Today on Knee,” Toronto Star, April 12, 1988: H2.

29 Jim Proudfoot, “Gruber Expects Hot Time at Hot Corner,” Toronto Star, March 7, 1989: B1.

30 John Robertson, “New, Improved Kelly Gruber Is in a Groove,” Toronto Star, April 24, 1988: G2.

31 Dave Perkins, “Gruber Makes Untouchable List/Jays Third Baseman Is Pleased but Sore Finger Remains a Worry,” Toronto Star, February 26, 1989: G4.

32 Associated Press, “Gruber’s First in AL at Position,” Toronto Star, October 25, 1989: F1.

33 Ken McKee, “Star Readers Are Keen on Kelly, Naming Gruber Favorite Athlete,” Toronto Star, March 3, 1990: B1.

34 Neil MacCarl, “Toronto Writers Pick Gruber as Blue Jay Player of the Year,” Toronto Star, November 28, 1990: C7.

35 “Gruber’s Highest Paid in T.O. Sports History,” Toronto Star, February 13, 1991: A1.

36 Allan Ryan, “Outlook Grim for Gruber,” Toronto Star, May 5, 1991: C1.

37 Dave Perkins, “Whispers Are Wrong, Hurt Gruber Says,” Toronto Star, July 12, 1991: C3.

38 Allan Ryan, “Jays Not Trading Gruber: Gillick,” Toronto Star, November 15, 1991: C1.

39 Tom Slater, “Gruber Sets Sights on RBI Century Mark,” Toronto Star, March 29, 1992: G5.

40 Kristina Rutherford, “The Interview: Kelly Gruber on Pablo Escobar, ADHD, and the ’92 World Series.”

41 GruberBaseball.com, “About Kelly.”

42 GruberBaseball.com, “About Kelly.”

43 Ryan, “Afternoon of Good News for Gruber.”

44 TheScore.com, “World Series Memories: Kelly Gruber of the ’92 Blue Jays on Playing Through Pain,” https://www.thescore.com/mlb/news/829328, (accessed December 3, 2021).

45 Associated Press, “Gruber Surgery Reveals Injury,” Toronto Star, February 17, 1993: B1.

46 Canadian Press, “Jays Cleared in Probe of Gruber-Sojo Deal,” Toronto Star, July 9, 1993: D3.

47 “Gruber Released!,” Toronto Star, September 8, 1993: E1.

48 Mark Zwolinksi, “After Surgery, Gruber Hopes to Play Ball Again/‘Every Time I Point a Finger There’s Three Fingers Pointing Back,” Toronto Star, December 11, 1995: B5.

49 GruberBaseball.com, “About Kelly.”

50 Katie Hall, “Former Baseball Player Kelly Gruber Arrested on DWI Charge,” Austin-American Statesman, April 24, 2018, https://www.statesman.com/story/news/local/2018/04/24/former-baseball-player-kelly-gruber-arrested-in-austin-on-dwi-charge/10374722007/, (accessed December 3, 2021).

51 Gregory Strong, “Gruber Event Cut Short Over ‘Inappropriate Behaviour,’” National Post, June 16, 2018: FP17.

52 “Gruber Event Cut Short.”

53 Allan Ryan, “Gruber Set for ‘Homecoming,’” Toronto Star, June 6, 1993: E3.

54 Mary Alice Piasecki, “Shining Star: Tosca Gruber Shines Brightly in Austin’s Hot Real Estate Market,” Austin Business Journal, February 27, 2000, https://www.bizjournals.com/austin/stories/2000/02/28/focus1.html, (accessed January 5, 2022).

Full Name

Kelly Wayne Gruber

Born

February 26, 1962 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.