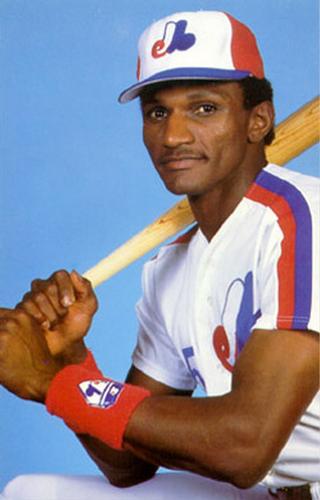

Otis Nixon

Otis Nixon’s baseball career was a rollercoaster that looked destined to derail before a low-profile trade to Atlanta in 1991 changed his course. He had three magical seasons with the Braves as an instrumental piece of deep playoff runs. He continued to contribute for multiple teams throughout his 30s. While hindered by troubles off the field, Nixon remains a popular figure in Atlanta for his part in triggering a dynasty with the most memorable catch in team history.

Otis Nixon’s baseball career was a rollercoaster that looked destined to derail before a low-profile trade to Atlanta in 1991 changed his course. He had three magical seasons with the Braves as an instrumental piece of deep playoff runs. He continued to contribute for multiple teams throughout his 30s. While hindered by troubles off the field, Nixon remains a popular figure in Atlanta for his part in triggering a dynasty with the most memorable catch in team history.

Nixon was in the middle of his most productive stretch as a major-leaguer when he made what Braves fans fondly remember as The Catch. July 25, 1992. Ninth inning. Atlanta-Fulton County Stadium. Braves up by one run against their rivals, the Pittsburgh Pirates. Man on first. Pirates All-Star Andy Van Slyke at bat. Braves reliever Alejandro Peña delivered the first pitch, one that caught too much of the plate. Van Slyke turned on it, sending the ball deep into right-center field. Nixon went back, full gallop. The ball descended. Nixon, a foot lodged in the padded wall, sprang upward, back first, glove extended long over his head … he snagged it nearly a foot beyond the top of the wall, robbing Van Slyke of a go-ahead homer.

When you think of Otis Nixon, a big aspect is his prodigious speed — his 620 career stolen bases ranked 16th as of 2020 — but the focal point is this game-saving catch. It was the moment a dynasty was born and the highlight in a long career that nearly never got going.

Otis Junior Nixon was born on January 9, 1959 in Evergreen, North Carolina. Sixty miles west of Wilmington, in Columbus County, this rural village had a population of just 300 according to the census conducted a year after Nixon’s birth. Otis’ dad, Artis, met his mom when he was 37 years old and she was roughly 16. They married and, together with their children, made ends meet on a leased tobacco farm. After his retirement, Otis said, “I didn’t realize the severity of our poverty since…everyone around our small community…were on the same page.”1 Nixon would later attribute his future mistakes to his childhood. “When you give a country boy that didn’t have any money $10 million, I didn’t know what to do,” he said.2

Otis and his younger brother Donell were athletes from a young age, spending much of their time together engaging in every sport they could. After starring for the baseball, football, and basketball teams at West Columbus High School in nearby Cerro Gordo, Otis chose to attend Louisburg College, roughly two and a half hours up the road from his home. Focusing on baseball, Nixon (at 6-foot-2, 180 pounds) was valued as a fleet-footed switch-hitter, expected also to play above-average defense at shortstop.

Nixon wound up being drafted a total of three times. First, the Cincinnati Reds selected him in the 21st round in 1978. Next, the Los Angeles Angels wanted him in the first round of secondary phase of the January 1979 draft. Finally, he signed with the Yankees when they took him third overall in the secondary phase of the June 1979 draft.

For his first go at professional ball, Nixon was assigned to the Paintsville (Kentucky) Yankees of the Appalachian League. There his .441 on-base percentage (OBP) was good for fifth in the league. However, it wasn’t until the following season, at Single-A Greensboro, that Nixon’s base-stealing ability blossomed, swiping 67 bags in 80 attempts.

Before the 1981 season, Nixon was promoted to the Double-A Nashville Sounds of the Southern League. Over 527 plate appearances, he slashed .251/.413/.283, making up for a lack of power by continuing to get on base and stealing even more, this time going 72 for 87.

Nixon spent 1982 between Double-A Nashville and Triple-A Columbus and had his best season yet. Between both levels he stole 107 bases in 137 attempts. For the fourth straight season, he notched over 100 walks and an OBP above .400. With Columbus full-time the following year, he picked up where he left off, stealing a league-leading 94 bases and batting .291. He had nothing left to prove in the minors, but he had played most games as a middle infielder, positions where the Yankees did not have a need. Second baseman Willie Randolph was still in his prime and shortstop Roy Smalley was still productive.

Columbus tested Nixon in the outfield and by September the Yankees felt he was ready for a taste of the big leagues. His first stint was less than memorable, as he batted .143 and stole just two bases over 13 games.

That offseason, the Yankees shipped the speedster to Cleveland as part of a package that landed New York Toby Harrah and minor leaguer Rick Browne. Nixon was now a full-time outfielder, but Brett Butler — an excellent leadoff man — was entrenched as Cleveland’s everyday center fielder. Nixon was a spare part during his four seasons with the club. He batted just .214 and stole a total of 57 bases as he shuttled between the big-league team and minor-league squads. Even Nixon’s on-base abilities dipped to .276 during his tenure with the Indians.

In the middle of the 1987 season, the same year his brother Donell debuted with the Seattle Mariners, Nixon was arrested on drug-related charges while playing for Cleveland’s Triple-A Buffalo Bisons. He was suspended by commissioner Peter Ueberroth before entering a rehabilitation program and becoming one of 12 major-league players subsequently required to be drug tested.

In October 1987, Nixon was granted free agency. The following March, he signed with the Montreal Expos, an organization known at the time for giving second chances to players with substance-abuse issues (such as Dennis Martinez and Pascual Pérez). Given a fresh start, Nixon’s time with the organization started back in the minors, before a callup on June 21, 1988. In his first game with big club he batted leadoff and played center field. He recorded two hits and two steals. He never played another game in the minors.

In October 1987, Nixon was granted free agency. The following March, he signed with the Montreal Expos, an organization known at the time for giving second chances to players with substance-abuse issues (such as Dennis Martinez and Pascual Pérez). Given a fresh start, Nixon’s time with the organization started back in the minors, before a callup on June 21, 1988. In his first game with big club he batted leadoff and played center field. He recorded two hits and two steals. He never played another game in the minors.

The first season in Montreal provided a peek at the skills with which Nixon had teased years earlier. His overall production wasn’t tremendous, but he did bump his stolen base total to 46 in just 90 games, the first of 11 straight seasons with at least 35 steals. The following year, Nixon appeared in the most big-league games of his career to that point (126), making 53 starts in addition to time as a pinch-runner and defensive replacement. His numbers across the board dipped, including his stolen-base total (37).

Continuing to come off the bench in 1990, his age-31 season, Nixon increased his slash line to .251/.331/.307 and stole 50 bases in 63 tries. However, the Expos had a fine young emerging center fielder in Marquis Grissom.

Thus, after a decade of inconsistent playing time and heading into his age-32 season, Nixon became a “bargain basement” trade chip for a team in need of depth.3 On April 1, 1991, he was sent with minor-leaguer Boi Rodriguez to the Atlanta Braves, who had finished last in the West Division the year prior, for a player to be named later and Jimmy Kremers. Braves manager Bobby Cox saw something in Nixon and for the first time in his career assured him a fair chance. “I’m not going to stop you, I’m going to allow you to steal when you want to steal and I’m not going to stop you,” Nixon recalled Cox saying.4

Starting the season back in a platoon role, on June 4 against the Phillies, Nixon made an impression with his new teammates when he charged the mound after a close pitch by Wally Ritchie buzzed his knee and the next hit him in the thigh. A bench-clearing brawl ensued, and Nixon was ejected for the first and only time of his career. Twelve days later, Nixon broke the National League record and tied the modern major-league record by swiping six bases in one game. By the end of June, the Braves were above .500, with sportswriters even claiming they were riding an “Otis elevator to the top.”5

Heading into the All-Star break, Nixon was having by far the best season of his career, compiling 42 steals to go with a .314 batting average and .383 OBP. Hitting at the top of the order, Nixon was the catalyst for a revamped and suddenly potent Atlanta offense. Yet in another abrupt change in his fortunes, he was derailed once more by the demons which he has spent a lifetime battling.

In mid-September 1991, with the Braves standing atop the NL West, commissioner Fay Vincent announced that Nixon had violated his aftercare program and the commissioner’s office drug policy for a failed drug test, as a result of cocaine use. “I had a void in my life at the time and I filled that void with drugs and I nearly lost it all,” Nixon later said.6 A 60-day suspension was levied, forcing Nixon to miss the playoffs and what ultimately turned into Atlanta’s first appearance in the World Series. Without their leadoff hitter, the Braves lost a seven-game classic to the Minnesota Twins.

Even in the shortened season, Nixon managed to set the post-1900 single-season record for the Braves franchise with 72 steals. He entered the best three-year stretch of his career, finishing the season with career highs up to that point in batting average, runs batted in, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, walks, and doubles.

Nixon was just one offseason removed from being cast away, yet the Braves — undeterred by the suspension — were engaged in a bidding war with the California Angels for his services. On December 12, Nixon signed a deal worth over eight million dollars. For the first time in his career, he was firmly planted as the starting center fielder and leadoff hitter for a team expected to contend for a championship.

Nixon had to spend nearly the first month on the sidelines, serving the end of his suspension. Asked about missing Opening Day, Nixon commented, “I’ve been in there only once,” referring to his time in Cleveland eight years earlier.7

With expectations riding high, Atlanta got off to a disappointing start. When Nixon returned on April 24, his team sat last in their division, five games under .500. Nixon, for his part, hit the ground running and got off to the best start of his career. In his fifth game back, he recorded three hits and soon after he compiled four straight multi-hit games. After spending May barely above water, the Braves entered June clinging to fifth place in the National League West, albeit just five games out of first place. Meanwhile, the Pittsburgh Pirates, their opponent from the prior season’s NLCS, had already pulled away in the East.

Anchored by an offense led by defending NL MVP, Terry Pendleton, and a pitching staff fronted by future Hall of Famers John Smoltz and Tom Glavine, the Braves kicked it into another gear when the calendar turned to the summer. Nixon’s timely hitting and havoc on the basepaths continued to set the table and give opposing teams fits. Overall, the Braves finished June 19-6 but remained two and a half games out of first place. The team was only getting started. They headed into a late-July statement series against the dominant Pirates on an 11-game winning streak and a game up in the East.

The Braves took the series opener in a tight 4-3 victory. In the second game, both starting pitchers were lights out, with the Pirates’ Danny Jackson surrendering just one hit, a second inning home run to David Justice, over seven innings. Going into the ninth, the Braves held a 1-0 lead. Reliever Alejandro Peña gave up a one-out single to Jay Bell, before delivering the pitch to Andy Van Slyke that sent Nixon up and over the center-field wall, saving the game and signaling a new phase in the Braves’ successful season.

By August 2, Atlanta was in first place and stayed there for the rest of the year. Nixon finished the regular season batting .294 with 41 stolen bases.

The Braves once again beat the Pirates in seven games in the NLCS. In his first taste of postseason play, Nixon batted .286 with a .375 OBP and three stolen bases. The Braves lost in the World Series, this time to the Toronto Blue Jays, but Nixon remained valuable, batting .296 and stealing five bases over six games. With the tying run on third in the 11th inning of Game Six, Nixon attempted to bunt for a base hit but made the final out of the series. It was only the second time in history that a World Series ended on a bunt.8 Indeed, the Jays were aware that Nixon, known for his skill in this aspect of “small ball,” might try to lay one down.9

After two straight World Series defeats, Atlanta signed reigning Cy Young winner Greg Maddux in the offseason and went into 1993 hungry to finally finish the job. Unfortunately, the pattern from the previous season only got worse. The Braves found themselves nine and half games behind the San Francisco Giants in early August. Nixon, finally playing a full season with the club, regressed in batting average, but showed slight jumps in both stolen bases and OBP.

In a turn even more striking than the prior season’s, the Braves went 22-8 after September 1 as the Giants went 18-13. The teams remained tied at 103 wins going into the last game of the season. A Braves win over the Colorado Rockies and a Giants loss to the Los Angeles Dodgers propelled Atlanta into the NLCS for the third straight time. Nixon catalyzed his team’s success in the hot streak by batting .325, getting on base over 40% of the time, stealing 16 bases and walking 22 times against just 13 strikeouts over 30 games.

However, for the first time in three years Atlanta didn’t advance to the World Series, losing to the upstart Phillies in six games. Nixon still managed to hit .348 with a .464 OBP over 23 at-bats.

After three postseason exits, the Braves let Nixon become a free agent. He signed a two-year deal with the Boston Red Sox worth $7 million.10 Boston hoped Nixon would fill “three prominent holes… a quality defensive center fielder, speed, and a leadoff hitter.”11 Even though Nixon had just come off the best seasons of his career, he was now 35 years old. Nevertheless, his first season with the Red Sox was virtually a carbon copy of his year before. He batted .274 with a .360 OBP and 42 steals. But Nixon’s presence didn’t move the needle in the standings for his new club — in the strike-shortened season, the Red Sox finished below .500 for the third year in a row.

Searching for a power bat to take advantage of Fenway Park’s Green Monster, Red Sox GM Dan Duquette shipped Nixon and a minor-leaguer to Texas for Jose Canseco.12 With Texas, Nixon put up arguably his finest statistical season by amassing career highs in hits (174), runs (87), and RBIs (45) to go with his usual strong stolen base total (50), batting average (.295), and OBP (.357).

The effort wasn’t enough for Texas to re-sign Nixon. Facing budget limitations, the club prioritized signing pitcher Kenny Rogers and lost various players in free agency — only to lose Rogers as well. Nixon agreed to a two-year contract with the Toronto Blue Jays, who needed to fill the hole left by the departure of free agent Devon White.

The Blue Jays got from Nixon exactly what they expected in 1996. Keeping up his consistency, he batted .286 with a .377 OBP and 54 stolen bases along with above-average defense as an everyday center fielder. Stuck in a division with three powerhouse teams, the Jays only managed to finish in fourth place, 14 games under .500.

The following season, Nixon was once again entrenched as the starting center fielder. Though his batting average dipped to .262, he had already swiped 47 bases by early August. With the Blue Jays in last place, they shipped Nixon to the Los Angeles Dodgers, who were in a divisional race with San Francisco. Nixon found himself playing alongside Brett Butler, whom he had backed up in Cleveland a decade earlier. Butler had been shifted to left field in July. Nixon managed another 12 steals, as he batted .274 over 175 at-bats. Ultimately, the Dodgers missed the playoffs by two games.

For his age-39 season, Nixon joined the Minnesota Twins. On April 4, while sliding into second base to break up a double play, Nixon’s jaw was broken when shortstop Félix Martínez was unable to make the throw and kicked his out leg into Nixon. Immediately after the incident, Nixon said, “It didn’t look good… didn’t like what I saw.”13 Nixon eventually accepted an apology from Martinez. He missed only three games because of the injury and continued batting with a face mask. Missing time throughout the year, Nixon still managed to hit .297 over 448 at-bats. For the first time in 10 seasons, he stole under 40 bases (37), but still led his team.

In what turned out to be his final season, Nixon signed with Atlanta, the team with which he’d enjoyed his greatest success. With the Braves coming off the best regular season record in the National League, Nixon would have another chance to see the postseason. Backing up star center fielder Andruw Jones, the now 40-year-old outfielder finally showed signs of wear. His usually steady batting average dipped to .205 and he stole just 26 bases in 84 games.

The Braves did make the postseason and Nixon remained on the roster for all three series, even though he collected just three at-bats. In the NLCS, Nixon found himself in a pivotal moment. He came in to pinch-run with the Braves down 8-7 in the eighth inning of Game Six and leading the series 3-2. He stole second base and advanced to third when the throw went into the outfield. He later scored the tying run and the Braves eventually won in extra innings. Over 24 career postseason games, Nixon gathered 93 plate appearances, batting .326 with a .396 OBP, plus 11 steals.

That offseason, Nixon entered free agency once more. Not receiving any substantial offers for his services, he chose to retire. In a career that looked like it might stall early, Nixon wound up playing for nine teams over 17 major-league seasons. He compiled 1,379 hits, a .270 batting average, 878 runs, and a respectable .343 OBP.

In an era filled with prolific base-stealers, Nixon swiped 1,080 bags between the majors and minors. He never led his league in any season at the top level, but for 11 years he was in the top 10. His 76.9% success rate puts him ahead of noted base thieves in the Hall of Fame, such as Willie Mays, Lou Brock, and Jackie Robinson. And since he retired, only one man has approached Nixon’s total of 620 in the majors: Juan Pierre (614). In fact, besides Pierre, only José Reyes and Ichiro Suzuki have passed the 500 mark.

Nixon appeared on the BBWAA Baseball Hall of Fame ballot in 2005. In a year that saw the elections of contemporaries Wade Boggs and Ryne Sandberg, Nixon was one of just two eligible players who received zero votes.

In 2000, Nixon married R&B star Perri “Pebbles” Reid, in what turned out to be the first of two short marriages with singers. The couple divorced in 2004. In 2010, Nixon married gospel singer Candi Staton; the pair split in 2012.

The demons that haunted Nixon’s baseball life continued to follow him into retirement. In 2004, he was arrested twice for possession of cocaine. As part of an ongoing effort to right his ways, in 2006 he started the Otis Nixon Celebrity Golf Tournament, an event that grew to become a major fundraiser for the faith-based Otis Nixon Foundation. This organization focuses on helping youth avoid the problems that Nixon himself has faced.

Nixon also wrote an autobiography called Keeping It Real (2009), which set out to directly address his substance abuse and offer guidance for others struggling with their own battles. About his addiction, Nixon said, “Drugs turned me into an ugly monster. I went to drug rehab several times and I could have died several different times. I didn’t. I’m here and now I’m going to help people through the word of God. I had to reach for God. It was a calling.”14

Even after that, Nixon relapsed into cocaine use. In May 2013, he was pulled over in suburban Atlanta for driving erratically. Upon further investigation, police officers found a pipe in Nixon’s pocket and what appeared to be crack rock scattered around the vehicle.15 He was sentenced to three years of probation for the charge.16

Shortly thereafter, on June 9, 2013, arson took place at one of Nixon’s homes after a dispute erupted between a neighbor and JanMike Mosley, the tenant living in the home with Nixon’s son. Nixon was not present or involved directly in the incident.

On April 9, 2017, Nixon was reported missing in Woodstock, Georgia by his girlfriend when he failed to show up for a scheduled tee time. Two days later, Woodstock police announced that Nixon had been located and was safe.17

Otis Nixon perseveres in his work as a life coach and motivational speaker, seeking to change lives through his outreach. And even 20-plus years after the defining moment of his baseball career, team observers still rank Nixon’s gravity-defying catch as the greatest in Atlanta Braves history.18

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Nowlin and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Evan Katz.

Sources

Otis Nixon Foundation website: http://www.otisnixon1foundation.org/

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted Baseball-Reference.com, Retrosheet.org, and Shrpsports.com

Notes

1 Otis Nixon, Keeping it Real (self-pub., 2009).

2 Will Hammock, “Getting to Know … Otis Nixon,” Gwinnett Daily Post (Gwinnett County, Georgia), December 9, 2009.

3 Alan Drooz, “He’s a Real Steal,” Los Angeles Times, June 28, 1991.

4 Martin Gandy, “Interview with Former Braves Outfielder Otis Nixon,” Talking Chop, https://www.talkingchop.com/2010/12/24/1894966/interview-with-former-braves-outfielder-otis-nixon, December 24, 2010.

5 Alan Drooz, “He’s a Real Steal,” Los Angeles Times, June 28, 1991.

6 Dale Stubblefield, “Back from the Brink-Former baseball star Otis Nixon comes to town to share inspirational message,” Southern Standard (McMinnville, Tennessee), June 17, 2008.

7 Gordon Edes, “Nixon Puts Suspension Behind Him,” Sun Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale, Florida), February 25, 1992.

8 The other time was 1977, when Lee Lacy did it.

9 Paul Hunter, “‘Dude, watch the bunt’ — Mike Timlin recalls final out of ’92 World Series,” Toronto Star, October 16, 2015.

10 Sean Horgan, “Red Sox Sign Nixon for 2 Years,” Hartford Courant, December 8, 1993.

11 Sean Horgan.

12 Glen Johnson, “Red Sox Trade for Canseco,” Washington Post, December 10, 1994.

13 “Kick breaks Nixon’s jaw, gets his dander up,” Tampa Bay Times, April 6, 1998.

14 Dale Stubblefield, “Back from the Brink-Former baseball star Otis Nixon comes to town to share inspirational message,” Southern Standard (McMinnville, Tennessee), June 17, 2008.

15 Justin Peters, Ex-MLB Player Otis Nixon Arrested on Drug Charges, Looks Astoundingly Haggard in Booking Photograph,” Slate, https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2013/05/otis-nixon-crack-cocaine-ex-atlanta-braves-speedster-arrested-on-drug-charges-in-cherokee-county-georgia.html, May 9, 2013.

16 Shaddi Abudaid, “Otis Nixon Serving Sandwiches to Woodstock PD,” Cherokee Tribune & Ledger News (Canton, Georgia), May 11, 2017.

17 Tyler Conway, “Former MLB Player Otis Nixon Found by Local Police After Being Reported Missing,” Bleacher Report, https://bleacherreport.com/articles/2702815-former-mlb-player-otis-nixon-found-by-local-police-after-being-reported-missing, April 10, 2017.

18 Terence Moore, “Before Inciarte’s catch, there was Nixon’s,” MLB.com, September 23, 2016. (https://www.mlb.com/news/ender-inciarte-s-catch-vs-otis-nixon-s-catch-c202938156). Clint Thompson, “Here’s the catch: Otis Nixon will forever be remembered for epic grab,” Valdosta (Georgia) Daily Times, April 25, 2020.

Full Name

Otis Junior Nixon

Born

January 9, 1959 at Evergreen, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.