Kid Carsey

Pitcher Wilfred “Kid” Carsey achieved an 81-59 record for the 1892-95 Philadelphia Phillies, working an average of 317 innings per season. He was the antithesis of big hard-throwing contemporaries Cy Young and Amos Rusie. The diminutive Carsey frustrated hitters by delivering deceptive slow curves. He was normally cool and collected, but at times he was feisty and unprincipled, in baseball and in life.

Pitcher Wilfred “Kid” Carsey achieved an 81-59 record for the 1892-95 Philadelphia Phillies, working an average of 317 innings per season. He was the antithesis of big hard-throwing contemporaries Cy Young and Amos Rusie. The diminutive Carsey frustrated hitters by delivering deceptive slow curves. He was normally cool and collected, but at times he was feisty and unprincipled, in baseball and in life.

Wilfred Carsey was born in New York City on October 22, 1870.1 His parents were William A.A. and Adele Z. (Ostrander) Carsey. William Carsey worked in New York City as a mason and builder, and immersed himself in local, state, and national politics. A “self-declared activist,”2 he professed to be a labor leader and spoke publicly under that guise, but the labor unions he claimed to represent did not exist.3 In fact, he was a “first-rate con man” and front man for Tammany Hall politicians.4 Growing up in New York City, Wilfred had learned to use his fists. On March 5, 1890, young Carsey was with his father at the New York State Capitol in Albany when his father spoke out against a bill under consideration by the Senate Labor Committee. A scuffle ensued during which Wilfred punched a state assemblyman.5

Aside from politics, William was passionate about baseball. He had played the game, and possibly learned it, while serving in the Kansas Volunteer Infantry of the Union Army during the Civil War.6 He taught Wilfred the game, and they played together on amateur teams in New York City. Wilfred was a right-handed pitcher and William was his catcher. In 1887, on a team known as the Eccentrics, the 45-year-old father and 16-year-old son formed a “remarkable battery.”7 In one game, Wilfred struck out 19 batters.8 He became known as “Kid” Carsey, receiving a nickname that would stick with him throughout his career.

In May 1889, Carsey pitched ineffectively for the New Haven, Connecticut, team of the Atlantic Association and was let go. He returned home and joined the semipro New York Metropolitans, where his catcher and mentor was Bill Holbert, a former major leaguer. On July 7, he went the distance as the Metropolitans edged Sol White and the New York Gorhams, 8-7, in 11 innings.9 On August 8, Carsey and the Mets defeated the Newark, New Jersey, team of the Atlantic Association.10 “Young Carsey, under Holbert’s coaching, is becoming a good pitcher,” said the Brooklyn Eagle. “He is a promising youngster, has good curves and a cool head.”11

Carsey’s work attracted the attention of the Brooklyn Bridegrooms of the American Association, and he pitched for the Bridegrooms in two late-season exhibition games. He fared poorly on September 6, 1889, in a 10-1 loss to Jesse Burkett and the Worcester, Massachusetts, team of the Atlantic Association.12 But Carsey was impressive in hurling a three-hitter against Newark on October 1.13

The 19-year-old Carsey pitched for the Metropolitans in April 1890 before traveling west to join the Oakland Colonels of the California League. The Colonels were named for owner and manager Colonel Thomas P. Robinson. In Carsey’s first game with the team, he lost a close one, 9-8, to San Francisco on May 24. “The little fellow never became excited or rattled” and was “quick as a flash” fielding his position, said the San Francisco Examiner. As a baserunner he was a “trifle foxy”; he “tried to cut off about twenty feet” running from home to second and “simply smiled” when called out.14

How little was Carsey? The record books say he stood 5-feet-7 and weighed 168 pounds, but he may have been smaller. One source said his height was “about five feet,” surely an underestimate.15 Other sources gave his weight as 140 pounds.16

Carsey pitched regularly for Oakland and threw a pair of one-hitters against Stockton, on July 18 and August 29.17 His pitching motion was unconventional. Rather than swinging his arm forward to deliver the ball, he merely snapped his wrist, propelling the ball with “little or no swing to his arm.”18 Batters could not gauge the speed of the pitch from his arm motion. “His change of pace was as amusing as it was deceptive.”19

There was dissension on the 1890 Colonels. Carsey and several teammates disliked team captain Norris O’Neill, and they lost a game on September 19 allegedly through deliberate poor play in an attempt to embarrass him. An angry Colonel Robinson threatened to suspend the conspirators.20

On October 12, Carsey achieved the pinnacle of the season by throwing a no-hitter against San Francisco.21 But trouble was still brewing. After an exhibition game on December 7, he and O’Neill engaged in a fistfight. Carsey took his lumps but held his own against the bigger man; “O’Neill’s face was badly disfigured, his eyes being blackened and his forehead bruised.”22 Colonel Robinson supported his captain. “Carsey, although a good pitcher, has always been a disturbing element in the team,” said Robinson. “He was constantly growling at the players for not stopping base hits, and was often rebuked for his conduct and threatened with a fine. … Carsey couldn’t play in my team if he offered to play for a dollar a month.”23

Carsey returned to the East Coast. In 1891 he resided with his father in Washington, D.C., and pitched for the Washington team of the American Association. He made his major league debut in the season opener on April 8 and earned the victory as Washington nipped the Athletics, 9-8, in Philadelphia.24

Through games of June 24, Carsey’s won-lost record was 8-13. But he lost 13 of his next 14 decisions; his sole victory during that stretch was a five-hit shutout of the Athletics on July 27.25 At season’s end, his record was 14-37 and his 4.99 ERA was well above the league average of 3.71. Washington finished in the cellar, and the American Association folded.

Carsey was much improved in 1892 as a member of the Philadelphia Phillies in the National League. He compiled a 19-16 record, and his 3.12 ERA was slightly better than the league average of 3.28. He was helped by the Phillies’ six Hall of Famers: manager Harry Wright, pitcher Tim Keefe, first baseman Roger Connor, and outfielders Ed Delahanty, Billy Hamilton, and Sam Thompson.

There were several highlights during the season. Carsey shut out the Washington Senators on May 18.26 He beat the St. Louis Browns with a two-hitter on July 20 and a three-hitter on September 17.27 And with relief help from Duke Esper on July 23, he defeated Cy Young and the Cleveland Spiders.28

In 1893, the pitching distance was increased from 50 feet to 60 feet 6 inches. As expected, the league ERA jumped, to 4.66. Carsey achieved a 20-15 record for the Phillies with a 4.81 ERA. It helped that he pitched for an offensive juggernaut; the Phillies scored an average of 7.6 runs per game. After the season, he pitched for the NL-champion Boston Beaneaters in a tour of California.29

Carsey was not married to Martha Taylor when she gave birth to his son, William Arthur, in New York City on June 3, 1893. He pitched at New York’s Polo Grounds on August 10, 1893, losing, 11-5, to Amos Rusie and the Giants.30 The next day Carsey fled the ballpark upon learning a man was looking for him with a summons “ordering him to appear in court in answer to a suit for breach of promise brought by” Taylor.31 No more information about this situation has come to light.

The next year Carsey again benefited from the potent Phillies offense, posting an 18-12 record with a 5.52 ERA (the league ERA was 5.33). The 1894 Phillies scored 8.9 runs per game, and the team batting average was .350. Outfielders Delahanty, Hamilton, Thompson, and Tuck Turner each hit over .400. Even Carsey helped out at the plate. He entered the season with a .162 career batting average. But he batted .279 in 1894, and his 10th-inning single on July 5 knocked in the winning run against the Pittsburgh Pirates.32 It is unclear whether he batted left- or right-handed.33

As a pitcher, Carsey lacked a speedy fastball and made up for it with “a large assortment of puzzling drops and curves.”34 Philadelphia sportswriter Francis Richter explained:

A Carsey pitch “comes up apparently as big as a balloon and with hardly enough speed to put a dent in butter, and yet it is seldom hit hard, because Carsey ‘mixes ‘em up,’ and does not put the ball where a man wants it if he can help it. In addition … Carsey fields his position in first-class style, and holds the men closer to bases than any other local pitcher.”35

Carsey pitched with a crossfire motion, starting from the right edge of the pitcher’s rubber and striding further to the right, to send his curves at a tough angle for a right-handed batter.36 His right foot barely touched the right edge of the rubber; Pirates manager Connie Mack complained that it was an illegal delivery.37 Cap Anson, the venerable playing manager of the Chicago Colts, said about his team, “We murder speed pitchers. It’s the crossfire, slow drop curve pitchers like Carsey … who fool us.”38

Carsey’s stellar 24-16 record for the 1895 Philadelphia Phillies helped the team to a third-place finish. But his career soon spiraled downward. In 1896 his record was 11-11 with a 5.62 ERA. On June 1, 1897, the Phillies traded him against his wishes to a weak team, the St. Louis Browns, and over the next season and a half, his record was 5-20 with a 6.18 ERA. On July 1, 1898, the St. Louis Globe-Democrat declared that Carsey’s pitching is “worse than an amateur” and that “his career as a big league pitcher has come to an end.”39

But Carsey hung on a bit longer. He remained with the Browns through the end of the 1898 season, then played for the Cleveland Spiders, Washington Senators, and New York Giants in 1899, and for three minor-league teams in 1900: the Buffalo Bisons, Kansas City Blues, and Anaconda (MT) Serpents. He departed the Serpents after an ugly incident on September 8, 1900, in which he assaulted the team’s manager, Arthur “Dad” Clarkson. One of Carsey’s punches broke two of Clarkson’s teeth.40 In a last gasp, Carsey appeared in two games for the Brooklyn Superbas in July 1901. His career record in the major leagues was 116-138 with a 4.95 ERA.

For the next decade, except for one year (1907) as an umpire in the Tri-State League, Carsey was active in semipro baseball in New York City, as a player, manager, and promoter. On June 8, 1913, before a crowd of 3,250, a team of top female ballplayers known as the Chicago Bloomer Girls defeated a men’s semipro team at Union League Park in Washington, DC.41 Carsey had nothing to do with that affair, but it was such a hit with fans that he promoted a second game featuring the Bloomer Girls, to be played at the same ballpark on July 20, 1913. Three thousand fans attended the contest, only to find that Carsey’s Bloomer Girls were fake; they were men wearing wigs. The crowd rioted and demanded a refund, but no one received a refund. Carsey left town with the money, estimated to be $700.42

Six months later, when asked about the scam, Carsey was unapologetic. “I admit that I left Washington with the receipts of a ball game,” he said, “but did so to protect myself, as I learned that certain persons were out to double-cross me. I simply beat them to it, that’s all, and collected money which was due me.”43

After that, Carsey dropped out of the public eye, and little is known about his later years. It seems he continued to live in New York City; he was in Manhattan at the time of the 1940 US Census. In February 1951, at the age of 80, he was found at the Brooklyn Dodgers spring training camp in Vero Beach, Florida, squeezing 90 gallons of orange juice per day for the team. When asked what he thought of present-day ballplayers, he called them semipros. “Nobody has the speed of Amos Rusie,” he said. “We had to pitch to strike out a batter. There was no foul strike rule to help us.” He went on. “They called me a fooler. I made a study of every batter’s weakness and knew just where to throw the ball. Sometimes I’d get ‘em out and sometimes I wouldn’t.”44

In Miami, Florida, on March 29, 1960, Carsey died of pneumonia at the age of 89.45 He was interred at Our Lady of Mercy Catholic Cemetery in Miami.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Chris Rainey.

Sources

Ancestry.com, accessed August 2020.

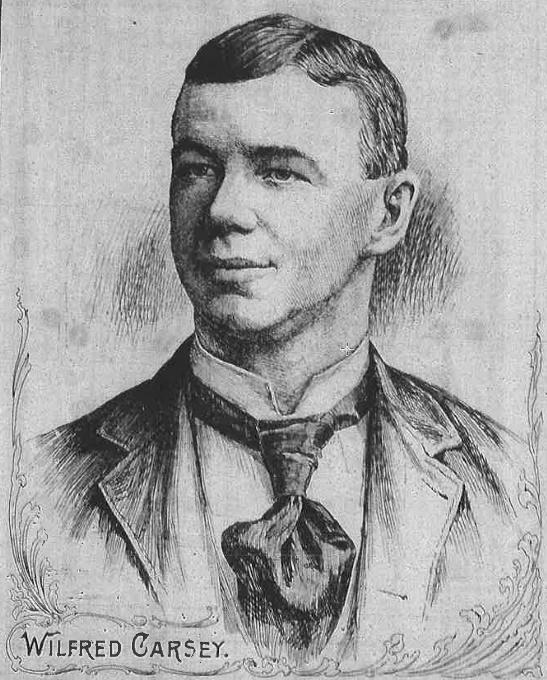

Image from the June 30, 1894, issue of the New York Clipper.

Notes

1 Carsey’s birthdate is given as October 22, 1870, on his Sporting News player contract card and in this article: “Kelly’s Magnificent Muscle,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Leader, September 15, 1889: 6. Carsey gave his birthdate as October 22, 1872, on his World War I draft registration, but the 1870 birthdate is consistent with mentions of his age during his playing career. He had three siblings, Lola, May, and Arthur, born in 1872, 1880, and 1884, respectively.

2 Jon Scott Logel, Designing Gotham: West Point Engineers and the Rise of Modern New York, 1817-1898 (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University Press, 2016), 161.

3 “Giving False News,” New York Times, October 25, 1886: 1.

4 Email communication from Mark Lause, Professor of History, University of Cincinnati, August 27, 2020.

5 “A Merry Mill,” Buffalo Commercial, March 6, 1890: 2.

6 Harold C. Burr, “Carsey Finds New Use for Gay Nineties’ Arm,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1951: 21.

7 “Great Pitching,” Brooklyn Citizen, May 13, 1887: 2.

8 “Baseball,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) News, August 11, 1887: 2.

9 “Other Games,” New York Sun, July 8, 1889: 3.

10 Brooklyn Eagle, August 9, 1889: 2.

11 Brooklyn Eagle, August 25, 1889: 15.

12 Brooklyn Eagle, September 7, 1889: 1.

13 “Brooklyn, 5; Newark, 2,” New York Times, October 2, 1889: 8.

14 “Down One More Notch,” San Francisco Examiner, May 25, 1890: 5.

15 “Sporting Matters,” New Haven (Connecticut) Journal and Courier, March 4, 1889: 4.

16 “Sporting Matters,” New Haven Journal and Courier, April 1, 1889: 3; “Sporting All Sorts,” Buffalo Times, April 2, 1897: 6.

17 “Only One Base Hit,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 19, 1890: 10; “Spoiled by an Umpire,” San Francisco Examiner, August 30, 1890: 5.

18 “The Umpire,” Oakland Tribune, July 2, 1890: 2.

19 “Back in Second Place,” San Francisco Examiner, August 11, 1890: 5.

20 “The Colonel Wild,” Oakland Tribune, September 20, 1890: 2.

21 “Played Pennant Ball,” San Francisco Examiner, October 13, 1890: 5. Carsey’s no-hitter on October 12, 1890, was in the second game of a doubleheader.

22 “Fought to a Standstill,” Oakland Tribune, December 8, 1890: 4.

23 “The Umpire,” Oakland Tribune, December 17, 1890: 6.

24 “Washington Wins the First,” Philadelphia Times, April 9, 1891: 3.

25 Statistics tabulated by the author from box scores appearing in Sporting Life.

26 Sporting Life, May 21, 1892: 3.

27 “A Pitcher’s Battle,” Philadelphia Times, July 21, 1892: 6; Sporting Life, September 24, 1892: 4.

28 “One from Cleveland,” Philadelphia Inquirer, July 24, 1892: 3.

29 “Two of a Kind,” San Francisco Call, December 3, 1893: 10; “Long Caused It,” San Francisco Call, December 26, 1893: 4.

30 Sporting Life, August 19, 1893: 4.

31 “Carsey Jumped the Turnstile,” New York Sun, August 12, 1893: 3; “Ball-player Carsey Must Answer,” New York World, September 7, 1893: 6.

32 “Ten Innings and Victory,” Philadelphia Times, July 6, 1894: 6.

33 Baseball-reference.com, accessed November 2020, indicates that Carsey was a left-handed batter, but his Sporting News player contract card says he batted right-handed.

34 “Early Base Ball Talk,” Philadelphia Times, March 20, 1892: 6.

35 F.C. Richter, “Philadelphia News,” Sporting Life, July 6, 1895: 3.

36 “Pitching Kings,” Buffalo Enquirer, December 7, 1895: 8; O.P. Caylor, “Caylor’s Ball Gossip,” York (Pennsylvania) Gazette, June 13, 1896: 5.

37 “Sporting Notes,” Pittsburgh Post, July 20, 1895: 6.

38 Sporting Life, August 10, 1895: 6.

39 “Crippled Browns Beaten,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 1, 1898: 10.

40 “Carsey Assaults Manager Clarkson,” Anaconda (Montana) Standard, September 9, 1900: 11.

41 “Columbias Lose to Bloomer Girls,” Washington Herald, June 9, 1913: 8.

42 “3,000 Fans See Fake, Then Mob Box Office Men,” Washington Herald, July 21, 1913: 1.

43 “Kid Carsey with Federal League,” Washington Herald, January 23, 1914: 9.

44 Harold C. Burr, “Carsey Finds New Use for Gay Nineties’ Arm,” Brooklyn Eagle, February 22, 1951: 21.

45 Carsey’s death certificate.

Full Name

Wilfred Carsey

Born

October 22, 1872 at New York, NY (USA)

Died

March 29, 1960 at Miami, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.