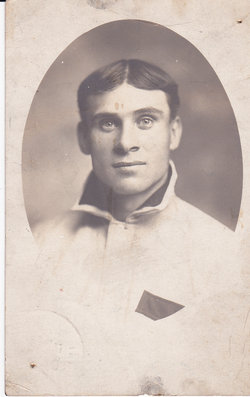

King Brockett

For the most part, pitcher-utilityman King Brockett owed his membership on major and high minor league baseball clubs to a single man: Deadball Era manager George Stallings. First as a third baseman-outfielder, thereafter as pitching staff ace, Brockett was a key component of Buffalo Bisons clubs led by Stallings, including the Eastern League champions of 1906. Brockett later served as a capable fourth starter for Stallings on the 1909 New York Highlanders, which finished in the middle of the AL pack. Perhaps ironically, subsequent reluctance to heed sportswriter and fan clamor for the release of an underperforming Brockett contributed to Stallings’ dismissal from the helm of Buffalo’s International League club in 1912.

For the most part, pitcher-utilityman King Brockett owed his membership on major and high minor league baseball clubs to a single man: Deadball Era manager George Stallings. First as a third baseman-outfielder, thereafter as pitching staff ace, Brockett was a key component of Buffalo Bisons clubs led by Stallings, including the Eastern League champions of 1906. Brockett later served as a capable fourth starter for Stallings on the 1909 New York Highlanders, which finished in the middle of the AL pack. Perhaps ironically, subsequent reluctance to heed sportswriter and fan clamor for the release of an underperforming Brockett contributed to Stallings’ dismissal from the helm of Buffalo’s International League club in 1912.

Two seasons later, Stallings sat atop the baseball world, the “Miracle Man” who had guided the Boston Braves to a worst-to-first National League finish and a World Series title in 1914. By that time, Brockett was back home in Illinois, organizing the first of the local semipro nines that he would play on or manage for the next 35 years. George Stallings is already the subject of an informative BioProject profile authored by Martin Kohout. The ensuing paragraphs recall the life and baseball times of a long-forgotten favorite of the renowned manager: King Brockett.

Lewis Albert Brockett was born on July 23, 1880, in Brownsville, Illinois, a sparsely populated downstate hamlet nestled in farming country near the border with southwestern Indiana. He was the older of two sons born to Samuel Matthew Brockett (1854-1946), a farmer whose WASP forebears traced back to Colonial America, and his first wife, the former Lucy Florence Newman (1862-1897). Lewis was educated locally through the eighth grade, and then went to work fulltime on the family farm. In his leisure hours, he played on various Brownsville-area sandlot baseball teams, often with one-year-younger brother Nathaniel, a left-handed pitcher.1

Athletically gifted, the right-handed Brockett brother played all over the diamond.2 At age 14, he won promotion from Brownsville’s juvenile nine to the adult club. He was originally a catcher, but a standout relief pitching effort led to a change in position. The game’s umpire remarked that young Lewis Brockett had “the best curve ball he had ever seen.”3

In 1899, a dominant outing against a club from the county seat, Carmi, led to Brockett’s entry into semipro ranks. He was signed for $75/month, plus free room and board, by the vanquished Carmi club. He pitched for the rest of the summer against teams from Evansville, Eldorado, Harrisburg, and other nearby locales, going a reported 25-3.4

A fast runner and bruising tackler, the good-sized Brockett5 also played a season with the Carmi football club. Only his lack of a high school diploma frustrated his recruitment for the University of Illinois eleven.6

The following season, Brockett played semipro baseball for a faster club located a bit farther north in Fairfield, reportedly achieving equal success.7 But midway through the 1901 season, he jumped to a still-faster club based in Cairo, Illinois, and remained there through 1902.

Lewis Brockett entered Organized Baseball in 1903 when the Cairo Egyptians were admitted to the newly organized Class D Kentucky-Illinois-Tennessee (KITTY) League. With staff ace Brockett (26-4) leading the way,8 Cairo posted a 67-41 (.620) record and cruised to the inaugural circuit pennant. Along the way, the Cairo Bulletin taunted the newspapers in other KITTY League venues, boasting of the Egyptians’ superiority to their clubs and demanding acknowledgment of Brockett as the “king” of league hurlers.9 The sobriquet stuck, and in time newspapers throughout the circuit were referring to the Cairo star as King Brockett.10 From that point on, our subject was regularly called King, occasionally Louis (but never Lew), in contemporaneous newsprint.11

During the season, Brockett caught the eye of a scout for the New York club of the American League,12 who dangled the prospect of a major league offer before him. Although only a modestly educated farm boy, Brockett was always cagey and tough-minded when it came to money. He agreed to sign with New York at season’s end, but only on the condition that the Highlanders select him in the upcoming September minor league player draft.13 And by the time that the draft came around, Brockett had another suitor: the Buffalo Bisons of the Class A Eastern League. Although New York had not selected Brockett, Buffalo’s draft of the prospect was nevertheless contested by the Highlanders. The National Commission, Organized Baseball’s governing body, ultimately ruled in Buffalo’s favor.14 Thereafter, young King Brockett signed with the Bisons for a $300/month salary, handsome for the time.15

Brockett made a good first impression in spring camp, with Sporting Life reporting that “Buffalo’s young pitcher Brockett in practice has shown up as the most promising youngster [manager] Stallings has on the roster.”16 Stallings himself was no less enthused about the new recruit, saying of Brockett, “There goes the young man who, if I am not mistaken, will develop into the pitcher of the year.”17 The Buffalo Times was also taken with Brockett, describing him as “a cracking good pitcher [and] a strong cool-headed fellow” with a deceptive delivery that made the speed of his pitches difficult for batsmen to gauge.18 In no time at all, Highlanders field leader Clark Griffith was reportedly trying to pry Brockett loose, offering Buffalo $1,000 for his release. The offer was declined.19

With Detroit Tigers alumnus Rube Kisinger (24-11) leading the Bisons staff, Buffalo went 88-46 (.657) and won the Eastern League crown handily. While hardly “the pitcher of the year,” King Brockett provided useful support. Making good use of a serviceable fastball, an excellent curve, and a spitter, he pitched to contact and posted a respectable 14-11 mark in his first season in topflight minor league company. A competent right-handed batsman, he also chipped in a .245 average in 106 at-bats.20

Brockett returned to Buffalo the following year and endured a season of stalled progress as a pitcher. Fooling around at second base during spring camp practice, Brockett exhibited a natural affinity for the position. He was “young, quick, good on pick ups, fast on his feet, and possessed of an excellent throwing arm.”21 Upon being informed of Brockett’s fielding prowess and then observing it for himself, manager Stallings promptly announced that the young pitcher was now the Bisons keystone sacker.22 But on Opening Day, Brockett was Buffalo’s right fielder. He then filled in at first and second base, before becoming the club’s everyday third baseman. As for pitching, King lost an early-season start and thereafter made only a handful of relief appearances, finishing the campaign with an 0-1 log.23 While his numbers as an offensive player were underwhelming (.228 BA, with 17 extra-base hits in 399 at-bats), his performance was good enough for him to be selected in the September minor league player draft by the Cleveland Naps of the American League.24 Meanwhile, the defending league champion Bisons struggled to a 63-74 (.460) record and a fifth-place finish in EL final standings.

Prior to the start of 1906 spring training, King altered his domestic situation, marrying Rosa Poole in the parsonage of a Methodist-Episcopal Church in St. Louis.25 In relatively short order, the couple had two sons, Hayward (born 1907) and William Harold (1908). Back on the diamond, Cleveland decided not to place Brockett on the roster and returned him to Buffalo.26 Restored to the mound for the new season by Stallings, the soon-to-be 26-year-old blossomed, joining Kisinger (23-12) as co-staff ace. Brockett went an outstanding 23-13 (.639), logging 313 innings pitched for a resurgent Buffalo club that recaptured the Eastern League pennant. He also did occasional duty in the outfield, and hit a solid .291 (41-for-141) with three home runs in 44 games played, total. As a result, Brockett was again selected in the September minor league player draft, this time by the Highlanders.27

Sober-minded and frugal, Brockett purchased a farm in the Southern Illinois village of Norris City with the money that he had earned as a pro ballplayer.28 This allowed him to institute the practice of invoking the need to remain home to tend to his crops whenever sent a baseball contract that did not meet his salary expectations, as New York player-manager Griffith was the first club leader to discover. Brockett demanded more money than Griffith was offering,29 but the two ultimately came to terms in time for King to join the Highlanders in spring camp.30 His arrival was preceded with predictions of great success, Detroit Tigers manager Hughie Jennings pronouncing him “a sure winner” for New York.31 Even Griffith himself was a Brockett booster, describing his new recruit as “a big right-hander with a world of speed … and a wonder at handling bunts and fielding his position in general.”32

During that camp, Brockett first encountered the pitching arm miseries that would plague his major league career. But benefiting from the salary holdout of staff stalwart Jack Chesbro, Brockett made the Opening Day roster for the pitching-thin New York club. He would also serve the team as an infield-outfield fill-in, if needed.

King Brockett made his major league playing debut on April 13, 1907, but in an unexpected fashion. In the top of the first inning of a game against Washington, Highlanders shortstop Kid Elberfeld was ejected for over-protesting a third strike call. The impromptu lineup shuffle that ensued found the tender-armed Brockett dispatched to right field. Against four Senators hurlers, he went 0-for-3, but with a walk and an RBI groundout, and caught the only fly ball hit his way in a 10-inning, 4-4 tie. Spelling right fielder Willie Keeler two weeks later, Brockett got his maiden major league base hit (an RBI single) off Washington right-hander Long Tom Hughes and scored his first run during an 11-2 thrashing of the Senators on April 25. Given his initial pitching chance a day later, Brockett was outstanding, effectively spacing six hits and five walks over eight shutout innings in a 4-0 whitewash of Washington.33

Brockett was ineffective in the infrequent pitching opportunities thereafter afforded him, and once Chesbro returned to the New York fold, the rookie became expendable. Brockett likely sealed his demotion with an unsightly relief outing in late June, combining with starter Earl Moore to surrender 19 base hits during a 16-5 trouncing by Washington.34 With his record standing at 1-2, with a 6.22 ERA in 46 1/3 innings pitched, Brockett was optioned to the Montreal Royals of the Eastern League in early July.35 Spending most of his time in the Montreal outfield — he went 4-3 in only seven mound appearances — it seemed that Brockett forgot how to hit, batting an anemic .144 (18-for-125) in 36 Royals games played. Nevertheless, the Highlanders exercised their option on Brockett and reserved him for the 1908 season.36

George Stalllings was installed over the winter as new manager of the Eastern League’s Newark Indians, and his first move as skipper was to purchase King Brockett’s release from New York.37 As had become his practice, Brockett declined to report to spring camp, the press of farm concerns and insufficient salary terms keeping him home until mid-May.38 Once finally in Newark livery, he was used exclusively as a pitcher by Stallings, going 11-7 (.611) for the third-place (79-58, .577) Indians before recurring arm problems brought his season to a premature halt in early September. Although unmentioned at the time, the strain of the 19-inning, 14-strikeout, complete-game scoreless duel that Brockett had with Ed Lafitte of the Jersey City Skeeters on July 5 may well have overtaxed his salary wing. Before Brockett went home, however, his contract was sold to the Boston Red Sox.39

On the heels of a last-place American League finish in 1908, Highlanders club boss Frank Farrell cleaned house. Placed in dugout command was none other than erstwhile Newark manager George Stallings. In February 1909, Stallings exercised the powers of his new post by purchasing from Boston the contract of an old Buffalo/Newark favorite of his: King Brockett.40 Stallings reportedly offered the pitcher a handsome stipend of somewhere between $4,000-$5,000 for six months labor.41 This time, Brockett readily signed his contract and reported to Highlanders spring camp.

As the regular season opened, King got off to a fast start, posting shutout victories over Philadelphia (1-0 on April 16) and Boston (2-0 on May 5) in his first two appearances. But soon thereafter, arm troubles and other ailments limited his effectiveness and productivity. In late July, Stallings dispatched Brockett to the vaunted spa in Mt. Clemens, Michigan, hoping that its medicinal waters would cure his ills.42 Whatever the spa’s effects, Brockett pitched well, if only sparingly, upon his return. On September 11, he threw probably the finest game of his major league career: a two-hit, six whiff blanking of the Washington Senators, winning 3-0. Four days later, Brockett bested Philadelphia in his final outing of the season, 3-2. Afterwards, chronic pain in his side idled him for the last three weeks of the Highlanders campaign.

For the year, Brockett was a useful-when-available fourth starter for New York, posting a creditable 10-8 (.556) record with an excellent 2.12 ERA for a sub-.500 club (74-77, .490). In 181 innings pitched, he allowed only 128 base hits, striking out 70 enemy batsmen while walking 59. Brockett also batted .283 in 60 at-bats to help his own cause.

The season prompted manager Stallings to remark over the winter that when Brockett “is right, he is just as valuable as any pitcher in the business.”43 Yet as it developed, the strong-willed right-hander sat out the entire 1910 season. The basis postulated by the press for Brockett’s stance constantly shifted. At first, it was said that King was remaining on his farm to reap the full benefit of high produce prices.44 Thereafter, a refusal to submit to the surgery required to repair injured side muscles was the excuse.45 Alternately, Brockett was simply resting his battered body for the summer and would return to baseball the following season.46 Finally and more plausibly, it was asserted that Brockett was simply holding out for a higher salary than the Highlanders had offered him.47 Whatever the truth of the matter, King spent the summer tending to his Norris City spread and pitching for various area semipro clubs on weekends.48 He remained, however, on the New York reserve list for the 1911 season.49

Brockett returned to the Highlanders the following spring.50 He avoided a fine for his previous season’s absence when the National Commission accepted his claim that he had sat out the year before to recover his health.51 But the layoff, arm troubles, and advancing age — Brockett was now nearly 31 — exacted a toll on his talents. And with star first baseman Hal Chase having supplanted George Stallings as New York manager the previous September, Brockett was no longer a favored player. Used intermittently as a spot starter and long reliever, Brockett was not particularly effective in either role. With a 2-4 record in 16 games for New York, he was released to the Rochester Bronchos of the Eastern League in mid-August.52

The demotion brought the major league career of King Brockett to a close. In parts of three seasons, all with the New York Highlanders, he posted a 13-14 (.481) record with a 3.43 ERA in 50 pitching appearances. In 291 2/3 innings pitched, he allowed 279 base hits and 124 walks, while striking out 108. As a hitter, he registered a .273 (33-for-141) batting average, respectable for the Deadball Era, with 16 runs scored and 10 RBIs. Including two games in the outfield and two at third base, Brockett was a career .915 fielder.

As it turned out, Brockett finished the 1911 season with Buffalo, not Rochester. This outcome came courtesy of the longtime friendship of Bronchos field leader John Ganzel and newly-returned Bisons skipper Stallings.53 A recounting of the drama that attended Stallings’ removal as ‘Highlanders manager in favor of Chase in September 1910 is beyond the scope of this profile. Suffice it to say that Stallings realized that bitter enemy Chase would never wittingly send player material to him, thus necessitating the need to enlist Ganzel in the subterfuge that enabled Buffalo to reacquire Brockett.54 But the manager’s pet was no great help to the Bisons this time, going 2-5 in late-season pitching action.55

Stallings’ retention of a clearly fading King Brockett for the 1912 season contributed to the loss of his managerial position in Buffalo. Brockett was quietly being paid $500/month by the club — well over the $350/month player salary limit instituted by the circuit, newly titled the International League. However, the usually fit hurler reported to camp 10 pounds over his playing weight.56 He was unable to get into shape during the regular season, and had little left besides (except at the plate where he hit .316 in 38 at-bats). Brockett struggled to a 3-3 record, trying to get by with off-speed stuff and pitch location. Soon, Buffalo sports reporters and fans began howling for the hurler’s release. Their calls went unheeded by Stallings until his old favorite became a luxury that he could no longer afford to employ.57 Brockett was released unconditionally in early July, and headed for home and, assumedly, retirement from the game altogether.58

The departure of Brockett was accompanied by a statement of explanation and regret by club brass: “While King’s work was far below par, he was a willing worker, always ready to jump in and help, regardless of his own welfare. He tried faithfully to round into condition and give the Buffalo team his best, but time demanded its reward, and Brockett could not accomplish his purpose.”59 In private, however, management was less understanding. The retention of Brockett was chief among the grounds for Stallings’ discharge at season end.60

Back home in Southern Illinois, Brockett entered the long and eventful second phase of his life. With his thriving farm producing more than ample income, King indulged his continuing passion for the game by becoming an investor in a newly-formed KITTY League franchise: the Harrisburg (Illinois) Coal Miners.61 Later, he could not resist the urge to play again, becoming the club’s second baseman and alternate pitcher, as well as co-manager with first baseman-club investor John Stelle, a local attorney-politico.62 Even Class D league hitters had no trouble hitting what little stuff Brockett had left; he posted a dismal 2-9 record in 11 outings. But King himself also found KITTY League pitching to his liking, batting a career-best .324, with 35 extra-base hits, in 120 games.

The following spring, Brockett left Organized Baseball to enter the world of local politics, running and winning as the Republican Party candidate for the post of supervisor of nearby Herald Township.63 When time permitted, he also kept his hand in the game playing for area semipro clubs.

Life was good for King Brockett until unspeakable tragedy hit the family in late October 1918. One evening, he permitted a coughing former farmhand to stay the evening at the Brockett residence. Within a week, wife Rosa and young sons Hayward and Harold were dead, victims of the deadly Spanish Flu epidemic.64 Devastated and suddenly alone, King soon gave up his farm and retreated to the nearby home of father Sam and his second family, where he reverted to working as a farmhand.

In 1920, King emulated his once-a-widower father, taking Calla Hill, a young widow with a four-year-old boy, as his second wife. Calla soon gave him a new son (Charles, born 1921) and a long and happy second marriage ensued. In his spare time, Brockett continued to play semipro ball until 1927, when he accepted appointment as the baseball coach at Illinois College, a private liberal arts school located in Jacksonville.65 In his first season in charge, the IC Blueboys posted an impressive 10-1 record in the highly competitive Illinois Intercollegiate Athletic Conference, aka the Little 19. Two years later, Brockett’s nine was conference champions. In early 1931, however, amid the Great Depression, Illinois College retrenched its athletic department. This precipitated Brockett’s dismissal as baseball coach.66 He thereupon returned to Norris City and opened a retail meat market.67

During the 1930s until as late as 1948, Brockett organized and managed the King Brockett All-Stars, an aggregation of former minor leaguers and semipro standouts that played throughout the greater Southern Illinois area. His last workplace was a state hospital in Elgin, Illinois.68 Finally retired, Brockett gave a reminiscence-filled 1957 interview in which he recounted his bygone diamond experiences and expressed gratitude for the love and encouragement that second wife Calla had provided him during the previous 37 years.69 Demonstration of his high leg-kick windup revealed that Brockett, by then 77 years old, was still physically fit.70 But the end for the old ballplayer was about to come into view — he was subsequently afflicted with terminal pancreatic cancer.

On the morning of September 19, 1960, Brockett was transported from his residence in Norris City to Ferrell Hospital in nearby Eldorado, Illinois. He died there 14 hours later.71 Lewis Albert “King” Brockett was 80, and had lived a long, interesting, and productive life. Following Methodist funeral services, his remains were interred in Odd Fellows Cemetery, Norris City. Survivors included wife Calla, son Charles, stepson Norris Hill, his brother Nathaniel, and half-brother Bernard Brockett.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Sources for the biographical info provided herein include the Brockett file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York; US Census and other government records accessed via Ancestry.com; certain of the newspaper articles cited in the endnotes, particularly a late-life profile of Brockett published in the Evansville (Indiana) Courier and Post; and a 2016 biographical essay by Norris City, Illinois, historian Edward Oliver posted on Ancestry. Unless otherwise specified, stats have been taken from Baseball-Reference.

Notes

1 The death of their mother in 1897 and father Sam’s 1900 marriage to May Mecum later provided the Brockett boys with much younger half-brother Bernard (born 1903).

2 For reasons undiscovered by the writer, baseball reference works from the 1969 first edition of The Baseball Encyclopedia published by Macmillan to current authority have listed our subject as Lew Brockett, a name nowhere found in reportage of his career. For a considerable time, newspapers and government records mistakenly gave Brockett’s first name as Louis. But for the most part, he was known as King Brockett, the sobriquet used herein. The effort to correct the reference work name applied to Brockett was ongoing when this bio was submitted.

3 Per Edward Oliver, “Lewis ‘King’ Brockett, Professional Baseball Player from Norris City,” August 16, 2017, 1, accessible via Ancestry.com.

4 Or so Brockett claimed in a late-life reminiscence. See J. Robert Smith, “When ‘King’ Signed with the Yankees,” Evansville (Indiana) Courier & Press, September 15, 1957: 64.

5 Modern reference authority lists Brockett as 5-feet-10½ and 168 pounds, but he was probably a bit bigger. In 1907, he was described as “built along the lines of pitcher Jack Powell” (5’11”/195 lb.). See Sporting Life, March 16, 1907: 3.

6 Brown, “Lewis ‘King’ Brockett,” 1.

7 Smith, “When ‘King’ Signed with the Yankees,” above.

8 Ibid. The 26-4 record is also cited in the AP obituary for Lewis A. (King) Brockett. See e.g., “Oldtime Yankee Dies at Norris City,” Evansville Courier & Press, September 20, 1960: 13; “Former Yankee Brockett Dies,” Milwaukee Journal, September 20, 1960: 35; “Former Yankee Hurler Dies in Norris City,” Rock Island (Illinois) Argus, September 20, 1960: 15.

9 As reflected in the response of the Clarksville (Tennessee) Leaf-Chronicle, September 18, 1903: 1.

10 See e.g., Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 1, 1904: 1, and Paducah (Kentucky) Sun, October 31, 1904: 3.

11 Beginning with his appointment as baseball coach at Illinois College in 1927, local newspapers sometimes referred to our subject as Lewis A. Brockett. See e.g., Jacksonville (Illinois) Journal, June 2, 1929: 8. But for the most part, he still remained King Brockett in newsprint. See e.g., Evansville Journal, September 7, 1931: 8, and Evansville Courier & Press, October 1, 1948: 21, reporting the activities of the semipro King Brockett All-Stars.

12 The American League Ball Club of Greater New York did not have an official nickname during its tenure at Hilltop Park (1903-1912), but was commonly called the Highlanders. The more headline-friendly Yanks or Yankees appeared in newsprint as early as 1904 but was not universally adopted until the club moved to the Polo Grounds for the 1913 season. For clarity’s sake, the New York club will be called the Highlanders in the instant text.

13 Smith, “When ‘King’ Signed with the Yankees,” above.

14 See “Selected by Draft,” Sporting Life, October 24, 1903: 5 (which identified the draftee as Louis Brockett of the Cairo club), and “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, April 2, 1904: 8.

15 According to Brockett in his 1957 interview with J. Robert Smith of the Evansville Courier & Press. A contemporaneous news account pegged the Brockett stipend at $250/month, still generous for an untested minor leaguer, per the Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, February 5, 1904, re-printing an undated dispatch published in the Cairo (Illinois) Bulletin. See also, “Just a Little Dope,” Evansville Courier, February 3, 1904: 5 ($250/month).

16 “Eastern League Events,” Sporting Life, April 2, 1904: 8.

17 Per “Buffalo Baseball Team Home Again,” Buffalo Courier, April 13, 1904: 11.

18 See “About the New Man,” Buffalo Times, April 12, 1904: 10.

19 Per “Base Ball Notes,” Clarksville Leaf-Chronicle, June 1, 1904: 1.

20 “Eastern League Averages,” Sporting Life, December 17, 1904: 9. Baseball-Reference provides only Brockett’s batting stats for 1904.

21 “Brockett for Second Base,” Buffalo Courier, April 7, 1905: 11.

22 See e.g., “‘Will Be in Good Shape,’ Says Stallings,” Buffalo Evening News, April 7, 1905: 28; “He Is Back in Harness,” Buffalo Morning Express, April 7, 1905: 9.

23 Per Eastern League statistics published in the Jersey (Jersey City) Journal, September 27, 1905: 7. Baseball-Reference provides no 1905 pitching stats for Brockett.

24 See “More Players for Cleveland,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, September 2, 1905: 8; “No Covering Up,” Washington (DC) Evening Star, September 2, 1905: 6.

25 As reported in “Pitcher Brockett Married in St. Louis,” Buffalo Evening News, February 8, 1906: 17; “Brockett Married in St. Louis,” Buffalo Morning Express, February 11, 1906: 22. Brockett’s bride was known as “the belle of Cairo,” according to “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, March 2, 1907: 9.

26 Per “Local Manager Due Here Today,” Buffalo Courier, February 21, 1906: 10, and “Sports Gossip,” Buffalo Times, February 21, 1906: 8.

27 As reported in “Big Leagues Buy and Draft Many Players,” Evansville Courier, September 4, 1906: 5: “Drafted Players for Next Season,” Washington Evening Star, September 5, 1906: 9; and elsewhere.

28 See “Brockett with Chicks,” Boston Herald, February 9, 1907: 11; “Brockett Goes to Boston (sic),” Topeka (Kansas) State Journal, February 13, 1907: 11; “Condensed Dispatches,” Sporting Life, February 16, 1907: 3.

29 See “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, March 2, 1907: 9; “Leave Chesbro Behind,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 7, 1907: 6.

30 Per “Brockett Joins Americans,” New York Times, March 9, 1907: 9. See also, Baltimore American, March 11, 1907: 12.

31 “Athletic Gossip,” San Jose (California) Mercury News, January 23, 1907: 9.

32 “Manager Griffith Not After Patten,” Washington Evening Star, February 7, 1907: 23.

33 A lengthy rain delay after the eighth inning prompted manager Griffith to send in right-hander Bobby Keefe to finish the game.

34 Highlanders catcher Branch Rickey contributed to the debacle by allowing 13 Washington baserunners to steal successfully, setting an unenviable one-game record for a major league backstop in the process.

35 Per “Wields the Ax,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 4, 1907: 7; “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, July 7, 1907: 57; “American League Notes,” Sporting Life, July 13, 1907: 9. Simultaneously sent to Montreal was New York pitcher Bobby Keefe.

36 See “Player Recalls,” Sporting Life, September 7, 1907: 5, and “Major List,” Sporting Life, October 22, 1907: 8.

37 Per “Brockett To Twirl for Newark,” Jersey Journal, February 26, 1908: 9; “Stallings Gets King Brockett,” Scranton (Pennsylvania) Republican, February 29, 1908: 10.

38 See “Eastern League Notes,” Sporting Life, May 23, 1908: 14.

39 As reported in “Brockett and Hughes Sold to Boston Red Sox,” Newark Evening Star, August 18, 1908: 7; “Boston Buys Two Newark Twirlers,” Washington (DC) Times, August 19, 1908: 11. The other Newark pitcher acquired by Boston was Salida Tom Hughes.

40 Per “Yankees Buy Two Men,” New York Times, February 9, 1909: 8. Salida Tom Hughes was the other hurler obtained by Stallings.

41 According to “The World of Sports,” (Baton Rouge) State Times Advocate, March 31, 1909: 5.

42 Per “Base Ball Notes,” Washington Evening Star, July 28, 1909: 3.

43 Per E.H. Simmons, “New York News,” Sporting Life, January 29, 1910: 6.

44 See e.g., “Carmi,” Evansville Journal, March 4, 1910: 9; “Quits Diamond for Farm,” Paducah (Kentucky) Evening Sun, March 16, 1910: 2.

45 See e.g., “Brockett Is Out of It,” St. Albans (Vermont) Messenger, March 15, 1910: 2; “Brockett Must Quit Baseball,” Grand Forks (North Dakota) Evening Times, March 16, 1910: 3; “The Passing of Brockett,” Trenton Evening Times, March 20, 1910: 27.

46 Per “Brockett To Rest for the Year,” Detroit Times, April 12, 1910: 4.

47 See “Tri-State News,” Evansville Journal, April 15, 1910: 8; “Baseball Briefs,” Buffalo Evening News, May 31, 1910: 60.

48 See “Flashes for Fans,” (Springfield) Illinois State Register, May 29, 1910: 11; “Short Sport Hash for Breakfast Reading,” Evansville Courier, June 19, 1910: 6; “Bens Win the Deciding Game,” Cairo Bulletin, August 8, 1910: 7.

49 Per “Major League Players,” Sporting Life, October 8, 1910: 16.

50 See “Pitcher Brockett Returns to Yankees,” New York Times, March 10, 1911: 10: “Brockett Again in Game,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 11, 1911: 8; “Base Ball Briefs,” Washington Evening Star, March 20, 1911: 14.

51 Per “Brockett Is Reinstated,” New Orleans Times-Picayune, April 7, 1911: 10; “Baseball Pointers,” Providence Evening Bulletin, April 8, 1911: 15.

52 As reported in “Rochester Gets Brockett from New York Americans,” Buffalo Commercial, August 12, 1911: 12; “Rochester Gets Brockett,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Union, August 12, 1911: 13; and elsewhere.

53 See “Brockett a Bison, Not a Hustler,” Jersey Journal, August 12, 1912: 7; “Brockett Goes to Work for Stallings, His Old-Time Boss,” Newark Evening Star, August 14, 1911: 10.

54 Among other places, more detail on the events that attended Stallings public charge of indifferent play, or worse, by first baseman Chase, and the ensuing AL President Ban Johnson-coerced dismissal of Stallings and his replacement by Chase as Highlanders manager is provided in the BioProject profile of New York club owner Frank Farrell.

55 Per final Eastern League pitching numbers published in the Providence Evening Bulletin, September 26, 1911: 16. Baseball-Reference provides no 1911 Buffalo stats for Brockett.

56 See “Buffalo Likes Athens,” Providence Evening Bulletin, March 30, 1912: 16, and “The International League,” Sporting Life, January 4, 1913: 4.

57 As subsequently revealed in “International Incidents,” Sporting Life, August 24, 1912: 15.

58 Per “Release Brockett,” Washington Times, July 7, 1913: 18, noting that Brockett “failed to acquire pitching condition” that season. See also, “King Brockett Is Given His Release,” Buffalo Courier, July 7, 1912: 53, and “Major and Minor,” Newark Evening Star, July 13, 1913: 12.

59 “Rochester Today,” Buffalo Commercial, July 8, 1912: 6.

60 See “Stallings Carried Too Many Dead Ones,” Jersey Journal, October 25, 1912: 11.

61 Per “Diamond Sparks,” Stockton (California) Evening Mail, January 28, 1913: 8; “News Items Gathered from All Quarters,” Sporting Life, February 1, 1913: 16.

62 Stelle went on to a long career in Illinois Democratic Party politics, including a tumultuous three-month stint as Illinois governor in 1940-1941. Two decades later, he was an honorary pallbearer at the Brockett funeral.

63 As reported in “An Ambitious Ball Player,” Evansville Courier, April 10, 1914: 7; “Ball Player-Politician,” Indianapolis News, April 10, 1914: 21; “Gossip of the Game,” Owensboro (Kentucky) Messenger, April 12, 1914: 7. Brockett’s victory in heavily Democratic Herald Township was deemed an upset. Years later in 1930, however, his Republican Party bid to become White County sheriff was unsuccessful.

64 Rosa Poole Brockett died on October 23, 1918, age 42. Her sons Hayward (11) and Harold (10) died seven days later.

65 As reported in “Former American League Hurler To Coach Illini Team,” Rockford (Illinois) Morning Star, March 22, 1927: 8.

66 As related in “College Feels Business Drop; Re-Outline Plan for Baseball,” Jacksonville Journal, February 22, 1931. See also, Bob Sink, “Along the Line,” Decatur (Illinois) Herald, March 2, 1931: 7. Brockett’s duties were assumed by IC basketball/assistant football coach W.H. Saunders.

67 Per “Former Yankee Pitching Star Now Is Proprietor of a Meat Market,” Evansville Press, May 31, 1931: 43.

68 According to the 1951 Elgin City Directory, Brockett and wife lived and worked on the hospital grounds.

69 Smith, Evansville Courier & Post, September 15, 1957, above.

70 The above-cited Courier & Post article included now-and-then photos of King Brockett’s pitching form.

71 Per the State of Illinois death certificate contained in the Brockett file at the GRC.

Full Name

Lewis Albert Brockett

Born

July 23, 1880 at Brownsville, IL (USA)

Died

September 19, 1960 at Eldorado, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.