Masanori Murakami

Long ago, baseball crossed the Pacific Ocean from the U.S. to Japan. Soon the reserve clause followed. It would reach back from Japan to the U.S. and bite its own tail, like a snake forming a ring that burst into fire–the “Working Agreement.” The first man it trapped was Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, the first Japanese player in Major League Baseball, and a man torn between loyalty and his dreams.

Long ago, baseball crossed the Pacific Ocean from the U.S. to Japan. Soon the reserve clause followed. It would reach back from Japan to the U.S. and bite its own tail, like a snake forming a ring that burst into fire–the “Working Agreement.” The first man it trapped was Masanori “Mashi” Murakami, the first Japanese player in Major League Baseball, and a man torn between loyalty and his dreams.

Murakami was a left-handed pitcher with a three-quarters delivery listed at six feet and 180 pounds. He was born on May 6, 1944, near the end of World War II, to father Kiyoshi and mother Tomiko. Mashi was the third child, after oldest sister Kyoko and middle sister Haruko.1 His father was gone, drafted into the army, captured in Manchuria, and a prisoner of war in a Siberian camp for three years post-war. Young Murakami was raised by his grandparents.2

His father’s father was postmaster of Otsuki, an isolated town west of Tokyo which avoided the destruction of war. His mother’s parents descended from samurai and displayed ancient samurai weapons in their home as family heirlooms. Young Murakami was allowed to play with these.3

On his fifth birthday, Murakami first met his father, released from the POW camp. Murakami had no idea what his father looked like. Up to then, he had been raised by his grandparents and a bit “spoiled.” Young Murakami soon learned his father Kiyoshi was strict and violent. Murakami said his father was “a scary person” and “if I didn’t do what he told me, he would slap me mercilessly.”4

Robert Fitts, author of the definitive book-length biography, Mashi (2014), wrote, “Today, [his father] would probably be diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder.”5

In post-war Otsuki, things were scarce. He and his friends played marbles and with menko (trading cards).6 Baseball was a bit makeshift. Because baseball equipment was unavailable, they had to improvise gear. For example, in a 2022 interview with Michael Clair of MLB.com, Murakami remembered, “I would cut a bamboo stick and find a softball and try to play baseball.”7

His father did not want him to play. He wanted his son to be a doctor. Murakami thought it was because his father had been injured in battle and saw so many wounded. By fourth grade, father had relented and allowed him to play softball. Young Murakami played barehanded, afraid to ask for a baseball glove. One of his sisters suggested that he write a letter asking for one and put it by father’s bedside while he slept. Young Murakami wrote the note, left it by his sleeping father, and got his first glove.8

In junior high school, his father, by then the Saruhashi postmaster, forbade him to play baseball.9 He wanted him in judo, so young Murakami tried. He didn’t like it and quit. The next year, against his father’s wishes, he secretly joined the baseball team at Saruhashi junior high. His mother found out but kept the secret.10

It wasn’t a secret long, for as postmaster, his father knew everyone. One practice, young Murakami saw his father across the field screaming at the manager, which left the young man shaken.11 His manager said, “I thought your father was going to punch me in the face.”12

Upon getting home, Mashi found his father sitting down between his two uncles. They told young Murakami to sit, and he did, afraid he was in trouble. Instead, his father told him the manager said that he was very talented at baseball.13 His father and the manager agreed: Murakami could play baseball if he studied and kept good grades.14

Later Murakami realized his grandfather intervened, convincing his father to let him play.15

The standout lefthander drew the attention of manager Hitoshi Tamaru, who invited Murakami to enroll at Hosei Number Two High School, which had a prestigious baseball program.16 Tamaru offered a scholarship, so father agreed.17

His father added, “If you want to be a ballplayer, you will have to be the best in Japan.”18

In Murakami’s first year at the prestigious baseball high school, there were about 200 players, but the practices were devised to frighten off the least dedicated, where each practice ended with a full-speed sprint, 10 laps around the field, and maintenance work on the grounds. Murakami said, “Every day, the number of members decreased by 20 to 30 people, and those who were absent were immediately dropped.”19 By year three, there were about 30 players left.

Murakami and Fitts while doing a nine-city tour to support the book “Mashi” gave a talk together at SABR 45. At the talk, Fitts said, “As some of you know, in Japanese baseball the training is very infused with the martial arts. Sometimes to toughen up the players they were not allowed to drink water.”20

Murakami added, “We could not drink the water. But sometimes we would very quickly drink some water. You would go to pick up the ball and there would be the little bit of water with the baby moquitoes [sic] in it. [Puddles.] Sometimes you would put a towel in that water and (*slurp*) [sic].”21

In high school Murakami loved watching the American TV western Rawhide.22 Through this and other U.S. shows, he found America fascinating.

His first chance to take part in Koshien, Japan’s national high school baseball tournament was in 1960. That time, however, he cheered from the stands, seated behind ace pitcher and future Yomiuri Giants outfielder, Isao Shibata. In 1961, he sometimes relieved, and Shibata played outfield. In 1962, he missed Koshien with a broken arm. Murakami said, “After the opening ceremony of the Kanagawa tournament, I went back to school and was pitching … when a ball hit my left wrist.… I tried to pick up the ball … and throw it. I couldn’t move my left arm…. I went to the hospital.… It was cracked.”23 He was unlucky in 1963, too. He got food poisoning during the qualifying Kanagawa tournament in Koshien and lost his stamina.

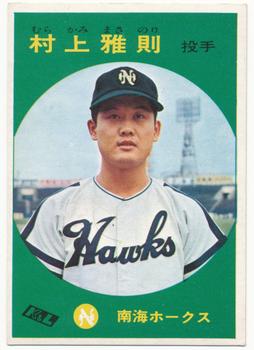

After the 1963 Koshien, Murakami was scouted by the Nankai Hawks of Japan Pacific League (JPPL). Hawks manager Kazuto Tsuruoka visited the Murakami family home. Tsuruoka’s son, Yashushi, raved about the young prospect. At first, though, Murakami refused to sign. He recalled, “my parents worked at a … post [office], so I thought I could take over after graduating from university.” 24

Tsuruoka said, “’If you join Nankai, I’ll send you to America to study baseball.”25

Murakami said, “I changed my mind. I had seen Rawhide, Hollywood movies with John Wayne and Marilyn Monroe, and I wanted to come [to America].”26 He signed.27

Japanese player contracts were translated from a copy of the standard Uniform Players Contract (UPC), including Section 10A, known as “the reserve clause”. Robert Whiting, author of several books on Japanese culture and baseball, wrote, “The Uniform Players Contract long used in the NPB was a descendent of a 1930s U.S. minor league contract. It had the same annoying reserve clause in it and it denied the right of collective bargaining.”28

During the Hawks’ camp, Tsuruoka took Murakami in with his family.29 They treated the 19-year-old as a son.30 Murakami felt deep loyalty to Tsuruoka.

With the Hawks’ “ni gun” or “second team”, the equivalent of the minor leagues, team in 1963, a coach told Murakami to throw overhand, and he did, injuring his elbow.31 Given several weeks to heal, Murakami returned and pitched through pain, losing effectiveness. Tsuruoka started to doubt that the lefty was major-league caliber.32 Murakami appeared in three games for the “ichi gun” or “first team”, the equivalent of the major leagues, but with a 4.50 ERA was no longer considered a prospect. 33

On February 20, 1964, Murakami was called to the manager’s office. Tsuoroka said, “You are going to the United States.”34 Catcher Hiroshi Takahashi and infielder Tatsuhiko Tanaka were going, too.35 General manager Makoto Tachibana thought none were major-league caliber.36

The Hawks sent Murakami to their representative, Tsuneo “Cappy” Harada, who also worked for the San Francisco Giants. In retrospect, the Hawks saw that since Harada worked for the Giants prior to working for Nankai, he might have a greater loyalty to the Giants and chose San Francisco’s best interest over Nankai’s, and they accused him of a “conflict of interest”37 Harada was close with Tsuruoka, whom Murakami trusted.38 Harada brought the contract to Murakami.

Fitts said, “The agreement [was] entirely in English and the Hawks didn’t notice the clause that says for $10,000 the Giants can just buy their contracts if the Giants wanted them.”39 Though he couldn’t read the contract, Murakami signed. There were not yet formal agreements between NPB and Major League Baseball.40

On March 10 he and the others flew to San Francisco.41 Murakami recalled, “Looking down on the ground from the sky over San Francisco, I felt like I was in a beautiful fairy tale land.”42

After landing he went to Candlestick Park to meet team officials. Still wearing his necktie, he stood on the mound.43 He thought, “I would be happy if I could pitch in a place like this.”44

Minor-league camp was in the Arizona desert, with mountains in the distance, reminding Murakami of cowboy movies.45 He recalled, “When we moved to … Phoenix, Arizona, we bought things like cowboy hats as souvenirs.”46

Their interpreter left after a week. Murakami was nervous. With the interpreter gone, Murakami and the other two Hawks spoke only Japanese, and had no one to translate to English for them to communicate with the team, but they carried Japanese-to-English pocket dictionaries. For many people they encountered in the U.S., it was the first-time meeting someone Japanese. They would approach and talk in English or Spanish. With a common language in baseball, they became friends. 47

Compared to NPB, U.S. baseball training was easy–out-of-shape players were slowly working themselves into playing shape and took care not to overdo it.48 Murakami said, “I [was] a little bored.”49

After practice, they would hitchhike to town to shop. He stopped after a while, as the money he had brought from Japan started running low and the team had not paid him.50 Murakami recalled, “In Japan, I got my salary every month from January, but in America, I didn’t get my salary until the season started.”51

Once camp was over, Murakami and the others were assigned to the Class A Fresno Giants. They arrived at the hotel expecting a Japanese American guardian, but the guardian never came.52 Murakami recalls, “When we moved to Fresno, California in mid-April, our sponsor took a long time to arrive, and we also had to pay for hotels. The 400 dollars I had brought in cash (about 144,000 yen at the exchange rate at the time) was quickly disappearing. I had to find a place to live on my own….”53

They tried getting a loan at the Tokyo Bank in town and had a lucky break, running into a second-generation Japanese American, Mr. Saeki, who spoke Japanese. He boarded them and drove them to the ballpark.54

During the first week of the season, Murakami finally got paid, a big relief. Two weeks later, he was alone. The other Hawks were sent to Rookie League. He was grateful to Mr. Saeki.55

At Fresno, manager Bill Werle converted Murakami into a reliever.56 In 49 games, the southpaw excelled, going 11-7 with a 1.78 ERA. He won California League Rookie of the Year.57 In late August the Fresno club was in a playoff race. Nonetheless, on August 29, Werle told his bullpen ace that he was going to the majors, and the next day he told Murakami what to do to report to the major leagues: “The minor league GM will bring you an air ticket and hotel address, so please follow his instructions.”58

Around then the Hawks sent a letter asking for Murakami to return to Japan, which didn’t arrive. Murakami was unaware of this when he was promoted to the majors.59

On August 31, he flew to New York. Nobody met him at the airport, so he took a bus alone to the hotel in Manhattan, only to find that he wasn’t registered. Murakami says, “I waited in the lobby for 20 minutes, and I felt depressed again.”60 He felt more alone than ever.

After two hours, a team representative arrived at last and got him a room. He went to the hotel restaurant to eat alone, but when Juan Marichal and José Pagán invited him to eat with them. He happily joined them. He could not read the menu, so he ordered what they did. He recalled, “I can’t help but have roast beef … since my salary is so low, I won’t be able to afford such a luxury [after this].” 61

On September 1, Murakami made his major-league debut in New York versus the Mets. Before the game, he visited the 1964 World’s Fair, and then went next door to Shea Stadium, which was still brand new. Murakami remembered, “It was more beautiful than the stadiums in Japan.”62

While he was warming up, an official from the Giants came up to him with a contract, which he refused to sign. At Fresno, others had warned him to beware of contracts – plus, he could not read English. Team officials found a fan who could translate to Japanese. Murakami signed it just 15 minutes before game time.63

That game turned out to be his big-league debut. The Mets were leading, 4-0, in the bottom of the eighth. The loudspeaker echoed across the field, “Now pitching! Number 10, Masanori Murakami.”64 He left the bullpen to take the mound before a crowd of nearly 40,000. Murakami described all four at-bats of his first major league appearance: “I threw a perfect strike on the outside, then [a strike]out, [a] hit, [a strike]out, and [a] groundout to short, and I was able to keep my debut score at zero.”65 The batters were, in order, Charley Smith, Chris Cannizzaro, Ed Kranepool, and Roy McMillan.

The next day, the newspaper headlines read, “First Japanese Major Leaguer.” Upon returning to San Francisco a week later after the road trip ended, he noted that “not only Americans but also people of Japanese descent had gathered at the airport to congratulate me.” He had become an international hero.66

Baseball historian John Thorn said, “Until he appeared at the major league level, the general supposition among fans and baseball professionals was that the Japanese professional league was the equivalent of Double-A at best. After Murakami, that was impossible.”67

Each performance broke down walls. Decades later in Time magazine, Dante Ciampaglia wrote, “[Murakami] pitched out of the bullpen eight more times in 1964…. With each throw, Mashi further legitimized Japanese baseball in the eyes of Americans.”68 Over the 1964 season, Murakami pitched in nine games, with a 1.80 ERA, and recorded his first career win on September 29 against the Houston Colt .45s, where he induced a popout from Joe Morgan.

After the season, he stayed in the U.S. to play in the Arizona Instructional League where a second-generation Japanese American fan loaned him a TV. Murakami watched Rawhide and The Bob Hope Show, remembering when he and other Giants were on the latter show.69 The TV and movies were his only news. He didn’t know what was happening in Japan.

He had not heard from the Hawks. Finally, he called his father, who perhaps didn’t understand the legal details but knew something was wrong, said, “Your position is strange,” and he eventually got in touch with the team, who said, “Just come back.”70 However, Murakami wanted to play for the Giants, so he signed a deal for 1965. Fitts said, “the Giants got him to sign a contract for 1965 because they knew they could get him for $10,000. But instead of mailing a check and the contract they handed it to a scout from the Hawks …the scout thought that the $10,000 was a bonus for him.”71

The Giants owned Murakami’s rights, through the U.S. reserve clause. On December 17, he returned to Japan.72 Back in his home country, he discovered the nation’s press saw his Giants’ contract as traitorous.73

The Hawks paid Murakami a $30,000 signing bonus. They couldn’t afford to lose both money and player, arguing that the $10,000 payment from the Giants was for making the majors.74 They tried getting out of the situation by having him write a letter to the Giants saying that he was homesick. They argued that under Japanese law he was still a minor and thus his signature on the Giants’ contract was invalid.75 Pressured, he signed a new contract with the Hawks.

The Hawks claimed his rights through the Japanese reserve clause, which conflicted with the U.S. reserve clause. Murakami was caught in the middle, torn between his loyalty to Tsuruoka and his dream of returning to the Giants.

U.S. Commissioner of Baseball Ford Frick thought the new Japanese contract crossed a line, responding, “If in the face of documentary evidence there still is insistence on the part of the Hawks baseball team in going through with this new arrangement and the breaching of the original contract, then as Commissioner of Baseball I can only hold that all agreements, all understandings and all dealings and negotiations between Japanese and American baseball are canceled.”76

In February, Murakami went to the Hawks’ camp in Hiroshima. He couldn’t play official games because of the legal limbo, so he pitched batting practice. When the season started, he still could not pitch official games.

For a month, his baseball career was in doubt. Representatives from NPB and Major League Baseball argued. Murakami remembered telling Tsuruoka that “was planning to quit baseball” out of frustration.77

For a month, his baseball career was in doubt. Representatives from NPB and Major League Baseball argued. Murakami remembered telling Tsuruoka that “was planning to quit baseball” out of frustration.77

NPB Commissioner Yushi Uchimura read the original contract, which the Hawks signed with the Giants allowing Murakami and the others to study baseball in America; finding it difficult to understand. He concluded that the Hawks didn’t understand it either.78 Uchimura offered a compromise. Murakami could fulfill the Giants contract, then return to Japan to honor the Hawks’ contract.79 In May, NPB and Major League Baseball reached agreement, and Murakami returned to the Giants.80

As a direct result of this incident Major League Baseball and NPB commissioners signed the “United States-Japanese [sic] Player Contract Agreement” (“Working Agreement”), where both leagues agreed to respect the other’s reserve clause.81 The “ring of fire” was now official. As Ciampaglia wrote, “The door Mashi so improbably opened slammed shut for other Japanese players—and it stayed sealed for 30 years.”82

Thorn added, “I think the Japanese professional baseball leagues did not want to become just a source of raw materials. They protected their best players with much more vigor afterwards.”83

Murakami returned to San Francisco on May 5 and celebrated his shared birthday with Willie Mays on May 6. He proceeded to have a good season, going 4-1 with a 3.75 ERA and eight saves in 45 games. Among them, Murakami closed the game in which Marichal attacked John Roseboro. From another game against the Cincinnati Reds, Murakami remembered Pete Rose flexing his biceps, bragging you had to be strong in Major League Baseball.

Another memorable meeting was with Roberto Clemente, who asked Murakami who was better, Clemente or Mays. Murakami said, “Mays.” Clemente asked, “Why?”84 Murakami was a fan of Clemente and asked for an autograph. Clemente obliged. Murakami said, “As [Clemente] was signing … he was telling me about … giving back to the community. That … stuck with me for a long time.”85

Murakami dealt with racism in the United States. Players would taunt him with slurs and pick fights. For a time, he pitched so well against the Dodgers that threats on his life had him under FBI protection.86 Despite that pressure, he did well.

At the 1965 season’s end, he returned to Japan to fulfill his commitment to Tsuruoka.87 He struggled during his first two seasons back with the Hawks. Murakami said, “I made two big mistakes: I put on too much muscle and I messed up my form.”88

After Rose’s bicep-flexing, Murakami thought, “Major-leaguers have amazing muscles.”89 Echoing the Babe Ruth woodchopping story, Murakami says, “I had a blacksmith make a masakari [battle axe] twice as big as the one at my parents’ house … I [split] the firewood … one year’s worth of wood in one month.”90

Also, in response to a newspaper story claiming that left-handed pitchers could only win pitching over the top, he switched his delivery to that style from three-quarters. This strained his arm, pained his shoulder, and hurt his performance. After a couple of failed starts, Murakami was moved to relief – a demotion, in NPB terms. In 1966, he went 6-4, although he posted a respectable 3.08 ERA in 96 1/3 innings). In 1967, he went 3-1 (4.03 ERA).91

In 1967 Murakami married Yoshiko Hoshino. They had two children: a daughter named Maho and a son named Naotsugu.92

By 1968 Murakami was demoted to the second team, where catcher Sumio Watarai advised him to stop throwing overhand and return to three-quarters. His form returned and he became a first-team starter. In his first start, on June 29 against the Osaka Kintetsu Buffaloes, he had a complete-game win. That was his best season, with a career high 18 wins against just four losses, for a league-leading winning percentage of .818.93 His ERA was a tidy 2.38.

From 1969 to 1972 Murakami averaged 22 starts per season, with a 43-44 record. In 1973, he pitched primarily in relief, with eight starts and 15 relief appearances. In 1974, he returned to relief full time, with a 1-2 record and a 1.82 ERA in just 10 appearances.

Traded to the Hanshin Tigers in 1975, he struggled with a 5.12 ERA. After just one season, he was dealt to the Nippon Ham Fighters, for whom he pitched in relief for seven more years. The Fighters won the Japan Pacific League (JPPL) pennant in 1981, with Murakami contributing a 3.72 ERA, but lost to the Yomiuri Giants in the Nippon Series.

He retired from playing in 1982 at age 38 after making just two appearances for the Fighters.94

In 1983, Murakami attempted a comeback with the Giants to fulfill his dream of playing with them again. They didn’t sign him, but he stayed on as a batting-practice pitcher.95

He returned to Japan as a sports commentator from 1984-1986. He was pitching coach for Nippon Ham’s minor-league team from 1987-1988, and later was pitching coach for the Fukuoka Daiei Hawks and Seibu Lions.

In 1995, Hideo Nomo joined the Los Angeles Dodgers. Murakami said, “I was very happy to see another Japanese player finally make it to the major leagues after all of these years.”96

That year the Giants honored him with a pregame ceremony, led by manager Dusty Baker, and August 5 was declared “Masanori Murakami Day” by the city of San Francisco.97

For a time, he worked as a Giants scout.98

Also, in 1995, Murakami remembered Clemente talking about charitable work, and he decided to engage in it too, donating to “the Special Olympics and to U.N.-related charities.”99

In 1999, 2000, and 2001 he was manager/general manager of Team Energen, the first all-Japan, women’s amateur baseball team.100 In 2004 he founded a new women’s team, Amino.101

In 2004, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan awarded Murakami the Foreign Minister’s Certificate of Commendation, commemorating the 150-year anniversary of Japan-U.S. relations. Murakami was director of the Imagine One World Kimono Project and a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador.

He currently works as Major League Baseball commentator for Japan’s public broadcaster, Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK), and as a writer for the Japanese newspaper, Daily Sports.102

He currently works as Major League Baseball commentator for Japan’s public broadcaster, Nippon Hoso Kyokai (NHK), and as a writer for the Japanese newspaper, Daily Sports.102

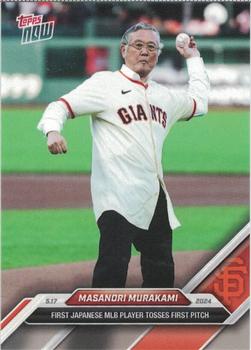

Murakami has returned to the U.S. on occasion. Notably, he joined the book tour for Mashi. Most recently, on May 17, 2024, he returned to San Francisco to throw out the first pitch at the Giants’ invitation. The occasion was Japanese Heritage night at Oracle Park. The 80-year-old lefty, with his usual easygoing smile, threw a strike from in front of the mound.

Looking back two years previously, Murakami offered Michael Clair his view on the two key themes of his baseball journey:

- Loyalty: “Mr. Tsuruoka was the one who promised me a ticket to the United States when I first joined the team, and he kept his word there … I do have pride that I kept my promise [to manager Tsuruoka.”103

- Dreams: “How I look at it now is that you only live once. Players that want to go from Japan and challenge themselves at the highest level should be going.… It’s your life.”104

Last revised: September 9, 2024

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello, Robert Fitts, and Howard Rosenberg, and fact-checked by Mark Sternman and Alan Cohen. Thanks to Rob Fitts for agreeing to let this version of Murakami-san’s life story proceed and for providing his input.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author consulted Baseball-Reference.com, www.baseball-almanac.com, and MLB.com.

Articles in Japanese were translated with Google Translate. Where possible, quotes from English articles were preferred, because in at least some of those cases, it is clear human translators were involved.

Translations of the Japanese text referenced in the endnotes are available from the author.

Notes

1 Robert K. Fitts, Mashi: The Unfulfilled Baseball Dreams of Masanori Murakami, the First Japanese Major Leaguer (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2014), 1, Figure 1.

2 Masanori Murakami, “40 years ago, there was a Japanese major leaguer,” Accumu.jp. Accessed August 4, 2024, Para. 2 and 3.

3 Fitts, 2-3.

4 Murakami, Para. 4

5 Fitts, 2.

6 Murakami, Para. 4.

7 Michael Clair, “Masanori Murakami, the Overlooked Trailblazer,” mlb.com, January 30, 2022. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www.mlb.com/giants/news/featured/masanori-murakami-first-japanese-player-in-mlb.

8 Murakami, Para. 4.

9 “My Failure 1: Masanori Murakami had a ‘broken bone’ in his second year of high school and ‘food poisoning’ in his third year,” Sanspo, August 18, 2015. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www-sanspo-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.sanspo.com/article/20150818-5MXFPEC3OZISZO7ZPCHWB7IOMA/?outputType=amp&usqp=mq331AQIKAGwASCAAgM%3D, Para. 3.

10 Fitts, 5.

11 Murakami, Para. 5.

12 Clair.

13 Fitts, 5.

14 Murakami, Para. 5.

15 Fitts, 5-6.

16 “My Failure 1,” Para. 3.

17 Fitts, 6.

18 Clair.

19 Murakami, Para. 7.

20 Cecilia Tan, “Masanori Murakami speaks at #SABR45,” whyilikebaseball.com, June 27, 2015. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www.whyilikebaseball.com/?p=973.

21 Tan.

22 “My Failure 3: Masanori Murakami is treated as a bad guy for remaining in the US,” Sanspo, August 20, 2015. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www-sanspo-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.sanspo.com/article/20150820-DPRMWG6KNVJDLHRNU7SBU4DZ3I/?outputType=amp&usqp=mq331AQIKAGwASCAAgM%3D, Para. 3.

23 “My Failure 1,” Para. 4.

24 “My Failure 2: Masanori Murakami is almost penniless in the United States,” Sanspo, August 19, 2015. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www-sanspo-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.sanspo.com/article/20150819-OB4HULKKENMH7F4YMUZFE5TJXA/?outputType=amp&usqp=mq331AQIKAGwASCAAgM%3D, Para. 7.

25 “My Failure 2,” Para. 9.

26 Tan.

27 Murakami, Para. 9.

28 Robert Whiting, The Meaning of Ichiro: The New Wave from Japan and the Transformation of our National Pastime (New York: Warner Books, 2004), 85-87

29 Tan.

30 Fitts, 2-3.

31 “Masanori Murakami,” Baseball Reference. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www.baseball-reference.com/bullpen/Masanori_Murakami.

32 Fitts, 27-30.

33 “Masanori Murakami,” Baseball Reference.

34 Fitts, 34.

35 “My Failure 2,” Para. 2.

36 “Masanori Murakami,” Baseball Reference.

37 “My Failure 3,” Para. 1 and 2.

38 “My Failure 3,” Para. 2.

39 Tan.

40 “My Failure 3.”

41 “My Failure 2,” Para. 3.

42 Murakami, Para. 10.

43 “My Failure 2,” Para. 3.

44 Murakami, Para. 10.

45 Murakami, Para. 11.

46 “My Failure 2,” Para. 5.

47 Murakami, Para. 12.

48 Clair.

49 Clair.

50 Murakami, Para. 13.

51 “My Failure 2,” Para. 1.

52 Murakami, Para. 14.

53 “My Failure 2,” Para. 5.

54 Murakami, Para. 14.

55 Murakami, Para. 14.

56 Tan.

57 “My Failure 2,” Para. 6.

58 Murakami, Para. 15.

59 “My Failure 3.”

60 Murakami, Para. 16.

61 Murakami, Para. 16.

62 Murakami, Para. 17.

63 Murakami, Para. 17.

64 Murakami, Para. 18.

65 Murakami, Para. 19.

66 Murakami, Para. 19.

67 Dante A. Ciampaglia, “Masanori Murakami: Baseball’s Forgotten Pioneer,” Time, July 14, 2015. Accessed May 27, 2024: https://time.com/3955421/masanori-murakami/.

68 Ciampaglia.

69 “My Failure 3,” Para. 69.

70 “My Failure 3,” Para. 5.

71 Tan.

72 “My Failure 3,” Para. 6.

73 Murakami, Para. 20.

74 Clair.

75 Clair.

76 Clair.

77 Murakami, Para. 20.

78 “Masanori Murakami,” Baseball Reference.

79 “My Failure 3,” Para. 6.

80 Murakami, Para. 20.

81 Whiting, 84-85.

82 Ciampaglia.

83 Ciampaglia.

84 Murakami, Para. 23.

85 Clair.

86 Murakami, Para 23.

87 Murakami, Para. 26.

88 “My Failure 5: Masanori Murakami lost his body shape after gaining muscle,” Sanspo, August 22, 2015. Accessed May 26, 2024: https://www-sanspo-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.sanspo.com/article/20150822-DEWSVYR5UNN6DB4OBAXJGZMMNY/?outputType=amp&usqp=mq331AQIKAGwASCAAgM%3D, Para. 1.

89 “My Failure 5,” Para. 3.

90 “My Failure 5,” Para. 3.

91 “My Failure 5,” Para. 8.

92 Fitts, 182-183, 186.

93 “My Failure 5,” Para. 4.

94 “My Failure 5,” Para. 4.

95 Michael Clair (in part), “Masanori ‘Mashi’ Murakami,” Japan American Society of Houston. Accessed May 27, 2024: https://www.jas-hou.org/masanori-murakami-bio.

96 Ciampaglia

97 Clair (in part).

98 Tan.

99 Clair.

100 “1st Season Team Energen Records,” girls-bb.com. Accessed May 26, 2024; “2nd Season Team Energen Records,” girls-bb.com. Accessed May 26, 2024; “3rd Season Team Energen Records,” girls-bb.com. Accessed May 26, 2024.

101 “6th Season Team Animo Records,” girls-bb.com. Accessed May 26, 2024.

102 Clair (in part).

103 Clair.

104 Clair.

Full Name

Masanori Murakami

Born

May 6, 1944 at Kita Tsuru-gun, Yamanashi (Japan)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.