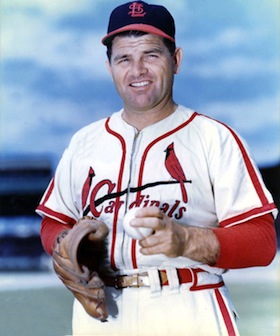

Max Lanier

A hard-throwing southpaw and two-time All-Star, Max Lanier won 45 games and posted an impressive 2.47 earned-run average from 1942 to 1944 for the St. Louis Cardinals, who captured three consecutive National League pennants and two World Series championships in those seasons. At the height of his career, in 1946, Lanier stunned baseball by breaking his contract with the Cardinals and jumping to the Mexican League. Suspended for five years from Organized Baseball, Lanier challenged baseball’s reserve clause in federal court. He dropped his lawsuit when he was reinstated in 1949. But in large part because of chronic elbow problems that developed early in his career, he never regained the form that had made him one of the big leagues’ best left-handed pitchers.

A hard-throwing southpaw and two-time All-Star, Max Lanier won 45 games and posted an impressive 2.47 earned-run average from 1942 to 1944 for the St. Louis Cardinals, who captured three consecutive National League pennants and two World Series championships in those seasons. At the height of his career, in 1946, Lanier stunned baseball by breaking his contract with the Cardinals and jumping to the Mexican League. Suspended for five years from Organized Baseball, Lanier challenged baseball’s reserve clause in federal court. He dropped his lawsuit when he was reinstated in 1949. But in large part because of chronic elbow problems that developed early in his career, he never regained the form that had made him one of the big leagues’ best left-handed pitchers.

Hubert Max Lanier was born on August 18, 1915, the fifth of sixth children of Stephen Ashley and Mittie Celina (Morris) Lanier, and was raised on his parents’ farm in Denton, North Carolina, located in the fertile grounds of central North Carolina about 70 miles northeast of Charlotte. Lanier was not a natural left-hander. When he was about 8 years old he broke his right arm above the elbow. His doctor set it incorrectly, requiring that it be broken again and reset. Once it healed, young Max returned to the pastures and fields to help his family on the farm and to the sandlots in his small town to play baseball. When he shattered his arm again at age 12, at the exact same spot, by cranking an old Model T Ford, the injury was more serious. With his right arm in a cast for months and immovable after that, Lanier began to throw with his left hand, though he continued to bat right-handed. “As far as I can remember,” Lanier once said about learning to pitch left-handed, “I always did the pitching. I could throw pretty hard as a kid, could strike out a lot of other boys, so my team always wanted me to pitch.”1 An athletic adolescent, Lanier earned letters in basketball, baseball, and track at Denton High School.

Despite his father’s protestations that baseball was a waste of time, Lanier played whenever he could and attracted the attention of scouts. Frank Rickey, the brother of St. Louis Cardinals general manager Branch Rickey, signed Lanier at the age of 17 while he was still in high school. Upon graduation in 1934, Lanier showed a glimpse of the independence, stubbornness, and concern for his own financial well-being that led to his jump to the Mexican League 12 years later. Desiring a fast track to the big leagues, Lanier balked at the idea of being sent to Martinsville in the Class D Bi-State League, claiming that he could earn more money playing semipro ball in North Carolina. The Cardinals relented and assigned him to the Greensboro Patriots in the Class B Piedmont League, but Lanier left the team after pitching just a third of an inning in two appearances, surrendering three earned runs and walking four.

For the next 2½ seasons Lanier played semipro baseball in nearby Emmons Township and Asheboro, North Carolina, in the highly competitive Carolina Textile League for $240 a month.2 “It was really a matter of money,” Lanier said several years later. “I could make a lot more pitching for the Asheboro mill team … than I could get from the Cardinals.”3 A local pitching legend of sorts, Lanier supposedly won 16 consecutive games in 1936, and again attracted the attention of big-league scouts. Chick Doak, the baseball coach at North Carolina State University and a part-time scout for the Philadelphia Athletics, recommended to manager-owner Connie Mack that he sign the hard-throwing 21-year-old. Mack approached Branch Rickey, since the Cardinals still owned the rights to Lanier. Mack’s interest rekindled Rickey’s curiosity, and the general manager sent his brother Frank to Denton in the spring of 1937 to persuade Lanier to reconsider professional ball. Promised an assignment with the Cardinals’ top affiliate, the Columbus Red Birds in the American Association, Lanier readily agreed to the new favorable terms.

Reporting to manager Burt Shotton’s Red Birds, Lanier impressed the Cardinals in his first full season of professional baseball. He made 38 appearances, including 12 starts, won ten of 14 decisions, and posted the league’s second-best ERA (3.06) in 147 innings. Lanier also won a game in the team’s seven-game Junior World Series loss to the International League’s Newark Bears. The Cardinals purchased Lanier’s contract after the season and invited him to his first big-league spring training in 1938.

Still a raw pitcher, Lanier struggled with control but his fastball and sweeping curve suggested unlimited potential. Lanier earned a spot in the bullpen for Frankie Frisch’s Cardinals and made his major-league debut on April 20, 1938, in the second game of the season, relieving starter Si Johnson and pitching two unspectacular innings (four hits and two runs) in a 9-4 loss to the Pittsburgh Pirates at Sportsman’s Park. With a 4.38 ERA in 15 appearances (including two brief, ineffective starts), Lanier was optioned to Columbus to work on his control. He earned a September call-up on the strength of a stellar 2.25 ERA over 44 innings, but finished winless in three decisions in his rookie season.

Lanier started the 1939 season with Columbus, which staggered to a 62-82 record, the Red Birds’ worst season since 1927.4 Depressed about his demotion, Lanier struggled with his control and concentration, and felt his dreams of the big leagues slipping away. A teammate, pitcher Max Macon, suggested that he start golfing to escape the pressure of pitching. The solitude, the concentration on the links, and an emphasis on hand-eye coordination helped. Despite 16 losses (fourth highest in the league) and a league-leading 105 walks in 200 innings, Lanier showed flashes of dominance, attested by his circuit-best 148 strikeouts. In another September call-up, he was thrust into a tight pennant race with the Cincinnati Reds. In his first start, on September 5 against the Reds, Lanier gave up two runs in the tenth inning and was charged with the 3-1 loss. On the 19th he tossed a complete-game five-hitter, and rapped two hits to earn his first big-league victory in a 6-1 win over the Dodgers that put the Cardinals 2½ games behind the Reds. Described as a “late-season sensation,” Lanier posted an impressive 2.39 ERA in 37 2/3 innings in September.5 The Sporting News compared the young lefty to former Red Sox star pitcher Dutch Leonard, saying, “[Lanier] is a well-constructed athlete with a lot of poise and judgment. He whips the ball.”6

Even before he arrived at spring training in 1940, the press touted Lanier as the Cardinals’ number-one southpaw. The Sporting News called him the “best among newcomers” in camp, a group that included Frank Barrett, Harry Brecheen. Murry Dickson, Preacher Roe, and Ernie White.7 Laboring through most of the season as a spot starter and reliever, Lanier was just 2-5 at the beginning of July and was described as the “biggest disappointment” in midseason for the underachieving Cardinals, who were 14 games below .500 on July 11. Unexpectedly, Billy Southworth, the team’s third manager of the season, transformed the Cardinals into the hottest team in the National League. They played at a 57-28 clip to salvage the season and finish in third place. Lanier concluded his season by pitching three consecutive complete-game victories, including a 12-inning 4-3 win over the Chicago Cubs in front of just 1,623 fans at Sportsman’s Park on September 28. He finished with a 9-6 record and a 3.34 ERA in 105 innings.

In 1941 Lanier developed elbow problems that he contended with for the rest of his career. His season was as erratic as it was frustrating. Through the first five weeks of the season he was limited to just 18 innings (and two starts, one of which was a complete-game victory). When healthy, Lanier pitched well. Beginning on May 27, he commenced his best stretch of the year, completed five of six starts, posted a 2.08 ERA in 52 innings, and proved that he was one of the most unhittable pitchers in the league (batters hit just .204 against him). Then, starting in late July, Lanier went almost two months without winning a start before concluding with a complete-game victory over the Braves on September 17 and a shutout over the Pirates on the 23rd. All the while, the Cardinals and Dodgers battled in an exciting pennant race that the Dodgers won by 2½ games. For the season, despite his elbow miseries, Lanier posted a 10-8 record and a stellar 2.82 ERA in 153 innings. Among his 35 appearances were 18 starts. Lanier’s tender elbow and inconsistency, coupled with 24-year-old left-hander Ernie White’s breakout season (17-7 and a 2.40 ERA) tempered the club’s expectations from him.

In 1942 the Cardinals began spring training in St. Petersburg, Florida, with the big leagues’ deepest pitching staff, boasting at least eight legitimate starters; all but 33-year-old Lon Warneke were products of the team’s farm system. Mort Cooper, Murry Dickson, Howie Krist, Lanier, Howie Pollet, White, and rookie Johnny Beazley all made at least 26 appearances and pitched at least 109 innings during the season. The Cardinals set a post-Deadball Era National League record for lowest team ERA (2.55), led by MVP Cooper’s league-leading 1.78 mark. Lanier’s 2.96 ERA was the highest of the home-grown group.

Elbow miseries limited Lanier to 11 appearances (seven starts) and extended periods of inactivity through June. In just his second start in five weeks, he tossed a six-hit shutout over Boston on July 24 to keep the Cardinals within seven games of the streaking Dodgers. With a healthy elbow at last, Lanier won his last three decisions in July and six of his first seven in August while the red-hot Cardinals went 22-9 in July and 25-8 in August to set the stage for a dramatic September. On September 12 Lanier held the Dodgers to five hits in a 2-1 victory at Ebbets Field in the final meeting of the two rivals. It was Lanier’s fifth victory against the Dodgers and gave the Cardinals a share of the lead. St. Louis won 12 of the remaining 14 games to capture the pennant by two games and set a franchise record with 106 victories.

Though Lanier distinguished himself in World Series competition over the years by posting an excellent 1.71 ERA in 31 2/3 innings, his first appearance in the fall classic, in 1942, was a forgettable one. Facing the New York Yankees in relief, Lanier, pitching the ninth inning in Game One, made two throwing errors and issued a walk in a 7-4 loss. He redeemed himself in Game Four. Entering a game tied 6-6, Lanier held the Yankees scoreless over the final three innings and drove in a run to earn the victory in the Cardinals’ comeback 9-6 win. Johnny Beazley won the next day to secure the Redbirds’ first championship since the Gashouse Gang in 1934.

During the offseason, Lanier tended his family’s farm in Denton. He married high-school sweetheart Lillian Bell (Doby) in 1934 shortly before he began his professional career. They had three children, Maxine, Betty, and Hal Lanier, who had a ten-year big-league career (1964-73) as an infielder for the Giants and Yankees. Lillie, Max’s wife, died on December 24, 1948, when her car skidded off an icy road. In October 1949 Lanier married Betty Cunningham, with whom he had a son, Terry.

Lanier was an avid hunter, fisher, golfer, and basketball fan. He played for the McCrary Eagles, a semipro basketball team from Asheboro, and competed against local colleges and other semipro teams in hoops-crazed North Carolina. A county boy at heart, Lanier was said to have a “fine moaning mountaineer hillbilly voice,” and enjoyed singing and playing the guitar and harmonica.8 When he came up with the Cardinals he played in Pepper Martin’s Mudcat Band, a bluegrass group made up of players. Later in his career with the Cardinals, he was known for monopolizing the clubhouse record player and playing country music before home games.

Lanier’s success in 1942 reignited discussions that he “could be the best southpaw in baseball” if he could stay healthy.9 The Sporting News wrote that Lanier “had more stuff than any other left-hander in the league.”10 He had a powerful overhand delivery to right-handers and dropped to a three-quarters to side-arm delivery to left-handers, making his curveball even more unhittable. He had a “blazing fastball” and effective change of pace, and beginning in 1942 a deceptive hard knuckleball.11

A victim of poor run support to start the 1943 season, Lanier lost two consecutive hard-luck complete games in May, a 13 1/3-inning effort against the Cubs (2-1) and a 9 2/3-inning outing against the Braves (4-3) by surrendering walk-off hits. After receiving extra time between starts to ensure that his elbow remained healthy, Lanier hurled his third extra-inning complete game of the month on May 28. He limited the Braves to five hits and scored the winning run himself in the bottom of the tenth on Lou Klein’s triple in a 2-1 victory. Boasting a 5-4 record and a 2.56 ERA, Lanier was named to the NL All-Star team for the first of two times in his career. Other Cardinals on the squad managed by Billy Southworth were Marty Marion, Stan Musial, Mort Cooper, and Howie Pollet. Lanier did not see action in the game.

The reigning world champions began a surge in July, winning 68 games and losing just 25 through the rest of the season. After the All-Star Game, Lanier (10-3 with a 1.51 ERA) was arguably the best pitcher in the major leagues, and with Mort Cooper (10-3, 2.68 in the second half) formed the most formidable lefty-righty combo in baseball. Lanier ended the season by tossing four consecutive complete-game victories and saving a game in relief. At season’s end he had a career-low and NL-leading 1.90 ERA. He surrendered just three home runs all season. The Cardinals had lost Harry Gumbert and Ernie White to injuries and phenom Pollet to the military, but reloaded with Harry Brecheen and Al Brazle and again led the league in team ERA (2.57).

In a rematch against the Yankees, Lanier started Game One of the 1943 World Series, which was played in a 3-4 format (with just one travel day) due to wartime travel restrictions. Lanier limited New York to seven baserunners (seven hits and no walks) over seven innings, but was undone by his own mistakes, as the Cardinals absorbed a 4-2 loss. His error on Frank Crosetti’s infield hit led to two unearned runs in the fourth inning; a wild pitch in the sixth inning allowed Crosetti to score and Billy Johnson to scamper from first to third (he later scored on a single by Bill Dickey). Lanier took the mound again in Game Four in St. Louis with the Cardinals down two games to one. He pitched seven strong innings, surrendering just four hits and one run, but did not get the decision in the Cardinals’ 2-1 loss. In the Yankees’ Game Five Series-clinching win, Lanier pitched 1 1/3 innings of scoreless relief. New York limited the Cardinals, who led the NL in hitting (.279) and were second in runs scored (679), to nine runs in the Series.

Touted as a future 20-game winner, Lanier began the 1944 season by hurling complete-game victories in six of his first seven starts. Included were three dominating shutouts: a two-hitter against the Pirates, a three-hitter versus the Cubs, and an overpowering three-hitter against the Giants on May 20 when he struck out a career-high 11 batters. After losing four starts, Lanier enjoyed a career-best ten-game winning streak in July and August while the Redbirds built an insurmountable lead for the second consecutive year. On July 2, Lanier tossed a career-high 14-inning complete game to beat the arch-rival Dodgers, 2-1. (From 1942 through 1944, no pitcher had more success against the Dodgers than Lanier, who defeated them five times each year and lost only three total.) Lanier was named to the All-Star team again, but Southworth chose not to pitch him, undoubtedly hoping to spare his elbow. The stocky lefthander concluded one of the most dominating extended stretches in his career (85 2/3 innings and a 1.37 ERA) by tossing his fifth and final shutout of the season (a five-hitter against the Giants) followed by his only career one-hitter in a 2-1 defeat of the Braves on August 22. It was Lanier’s 17th and last win of the season. Suffering from terrible swelling in his elbow, a pulled muscle in his back, and excruciating stomach pains (later determined to be a severe case of appendicitis requiring surgery), Lanier lost seven consecutive starts to end the season.

Despite fears that Lanier would miss the World Series against the surprising St. Louis Browns, with whom the Cardinals shared Sportsman’s Park, the feisty North Carolinian started Game Two and limited the Browns to five hits and two runs in seven innings, his longest outing in almost three weeks. The Cardinals won, 3-2, on Ken O’Dea’s pinch single in the 11th inning. In Game Six, Lanier fought back pain to pitch 5 1/3 innings of three-hit ball, surrendering one run, before yielding to Ted Wilks, who pitched 3 2/3 hitless innings to save the 3-1 victory that gave the Cardinals their second championship in three seasons. With the victory, Lanier improved his record to 2-1 in World Series competition.

Like all major-league teams, the Cardinals lost players to military service during World War II. When Lanier passed his Army physical in December 1944, it was assumed that he would be called to active service before spring training, joining Cardinal hurlers Beazley, Brazle, Ken Burkhart, Dickson, Krist, Red Munger, Pollet, Fred Schmidt, and White in the military. Said Cardinals owner Sam Breadon, “I have a better pitching staff in the service than Billy Southworth can put on the field.”12 Lanier’s record was 2-2 with a 1.73 ERA when he was inducted into the Army at Fort Bragg on May 24, 1945.13 He remained stateside during his abbreviated stint in the service, pitching and playing outfield on his camp team. The war ended in August and Lanier was discharged in October as a “hardship case” which eventually led to claims that he had received special treatment.14 After investigating, the military called the charges baseless.15

Throughout Lanier’s career, he battled with Breadon over salary. A contentious dispute after the 1944 season heightened the tensions and in early 1946 The Sporting News said there was a “strong feeling” that Lanier would be traded.16 Saying he was dissatisfied with the Cardinals’ contract offer, Lanier held out at the start of spring training and reported to camp late.17 The holdout apparently had no ill effects. Described as “faster than Feller” and in great shape, Lanier began the season with six consecutive complete-game victories, including two shutouts and an 11-inning effort against the Dodgers at Ebbets Field.18 Then the unthinkable happened. At the peak of his career, Lanier jumped to the Mexican League.

Jorge Pasquel, the president and leading promoter of the Mexican League, and his four brothers poured millions of dollars into the upstart league in an attempt to create a viable rival to the major leagues. Pasquel had successfully lured stars from the Negro Leagues in the early 1940s, and in 1946 actively recruited big leaguers with promises of exorbitant salaries to “jump” to his league. On May 23 news broke that Lanier, Fred Schmidt, and Lou Klein of the Cardinals had accepted Pasquel’s contract offers. “I can make more money down there in a few seasons than I could in a lifetime in St. Louis,” Lanier supposedly told his roommate Red Schoendienst.19 Unsubstantiated reports circulated that Lanier had received a $50,000 bonus and a five-year contract worth $30,000 a year. (Almost all major leaguers at the time signed one-year contracts and Lanier reportedly earned about $11,000.)20 Other big leaguers followed, among them All-Star catcher Mickey Owen and pitcher Sal Maglie. Commissioner Happy Chandler summarily suspended all “Mexican jumpers” from Organized Baseball for five years.21

By the time Lanier was reinstated in June 1949, he had lost three years of his prime (ages 30-32) while pitching in Mexico, winter ball in Cuba, in an independent league in Canada, semipro ball in the US, and as the leader of a barnstorming team. He admitted that his jump to the Mexican League was not what he expected, despite the immediate financial rewards. “I thought the conditions would be better,” he said, referring to poor fields and lighting, and unprofessional behavior.22 Pitching for the Veracruz team, he suffered from bursitis in his left elbow and inflamed muscles in his first season, and was ineffective.23 Throughout his season and a half in Mexico, he fought with the Pasquel brothers about his contract and extra pay during the postseason in 1946, and abruptly quit the league in 1947 after playing less than two months.24 Lanier was excoriated in the American press as an egotistical money-grubber who turned his back on his teammates. Reports published in The Sporting News about his struggles as a pitching nomad read like opening warnings to players against challenging the authority of baseball.

In 1948 Commissioner Chandler, and team owners vowed not to soften their stance against the 22 big-league “jumpers” Chandler had banned.25 In March 1949 Lanier and teammate Fred Martin filed lawsuits seeking $2.5 million in damages. They charged that baseball was a monopoly and the reserve clause was illegal, and requested immediate reinstatement. After two judicial rulings against reinstatement, it appeared as though Lanier and Martin might have their day in court; but rather than risk a test of the legality of the reserve clause, Chandler offered general amnesty to all the jumpers in June 1949. Lanier withdrew his lawsuit, citing exceptional “treatment and consideration” by the Cardinals organization in accepting him.26 The “game needs a reserve clause,” Lanier said publicly. “[It] preserves order [and] aids competition.”27

When Lanier returned to the Cardinals on June 24, 1949 (after playing briefly for Drummondville, Quebec, in the independent Provincial League), the 33-year-old had not pitched a full season in the big leagues since 1944, and had lost almost four years to the military and his suspension. Age and the years away had taken their toll. Before jumping, Lanier had a career record of 74-47 with a 2.63 ERA; after his return he was 34-35 and his ERA was a run higher (3.64).

The Cardinals were a team in transition when Lanier returned. Sam Breadon’s sale of the team to Fred Saigh and minority partner Robert Hannegan after the 1947 season had ended a long, successful run dating back to 1926. Lanier joined the Redbirds in an exciting pennant race in 1949, but it was the last time the team seriously contended until 1957, and the only time they finished higher than third place from 1950 to 1962.

In 1950 and 1951 Lanier won 11 games and lost 9 each season with ERAs (3.13 and 3.26 respectively) much better than the league average, but he was no longer a front-line starter. And the Cardinals’ pitching staff, always a strength during the Rickey years, had grown old. Lanier (35 years old), Brecheen (36), Brazle (37), Munger (32), and Wilks (35) had been largely together for almost a decade. With 23 starts among his 31 appearances in 1951, Lanier closed out his tenure with the Cardinals with a dominating stretch, evoking memories of 1943 and 1944. Beginning with a commanding two-hit shutout over the Reds on August 11, he hurled six consecutive complete-game victories, concluding with a ten-inning, 2-1 victory over the Pirates on September 9. It was Lanier’s last win in a Cardinals uniform. In December he was traded along with utilityman Chuck Diering to the New York Giants for infielder and player-manager Eddie Stanky, who succeeded Marty Marion as manager, the first skipper from outside the organization since Jack Hendricks in 1918.

The second-place Giants went 92-62 in 1952, but Lanier pitched inconsistently. In his debut he surrendered a career-high ten earned runs in a loss to the Dodgers, the team he had always dominated and one of the reasons manager Leo Durocher wanted to acquire him. Relegated to the bullpen and spot starting duty for much of May and June, he reeled off a streak of 25 1/3 scoreless innings, highlighted by his last big-league shutout (in a start against the Phillies on July 6) which earned him another chance in the rotation. With the Giants attempting to mount a challenge to the league-leading Dodgers, Lanier tossed a complete-game four-hitter to beat the Boston Braves on September 1. It proved to be his last win in the major leagues.

Described as a “flop” with the Giants in 1952, Lanier was released on May 15, 1953, and was picked up by Bill Veeck and the St. Louis Browns two weeks later.28 Reunited with Marty Marion (the Browns’ manager) and Harry Brecheen (in his last season), the 37-year-old Lanier was worn out. With a 7.16 ERA in 27 2/3 innings, he was released in July and his 14-year big-league career came to an end. He finished with 108 wins and a 3.01 ERA. His career 126 ERA+ (also called adjusted ERA, a metric that compares a pitcher’s ERA to the league’s ERA and adjusts it for ballpark factors) ranks him right behind Bob Gibson, Tom Seaver, and six others.

After being released, Lanier pitched in the Texas League with Shreveport (1953) and Beaumont (1954). In 1956 he attempted a comeback, first with the Philadelphia Phillies and then with the Miami Marlins of the International League, but was among the last players cut on each team.

Lanier settled in St. Petersburg, Florida, where he had been living with his wife, Betty. He was involved in varied business interests, including a restaurant called the Diamond Café, before returning to baseball in 1961 when the San Francisco Giants hired him as a scout, roving pitching instructor, and all-around trouble-shooter. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, he managed several low-level farm teams in the Giants, Phillies, and Tigers farm systems. In 1967 he was named manager of the year for the Batavia (New York) Trojans in the short-season New York-Pennsylvania League.

After his baseball days, Max and Betty retired to Dunnellon, Florida, about 100 miles north of St. Petersburg. He died on January 30, 2007, at the age of 91, and is buried in the Dunnellon Memorial Gardens.

A version of this biography appeared in “Van Lingle Mungo: The Man, The Song, The Players” (SABR, 2014), edited by Bill Nowlin.

Sources

Newspapers

New York Times

The Sporting News

Online sources

Ancestry.com

BaseballLibrary.com

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Other

Max Lanier player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, New York

Notes

1 The Sporting News, September 17, 1942, 3.

2 Dr. Harold and Dorothy Seymour, Baseball: The People’s Game (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990), 252.

3 The Sporting News, September 17, 1942, 3.

4 The Red Birds’ .403 winning percentage was their lowest since 1927, when they went 60-108 (.357). Bill O’Neal, The American Association. A Baseball History 1902-1991 (Austin, Texas: Eakin Press, 1991).

5 The Sporting News, January 4, 1940, 10.

6 The Sporting News, September 28, 1939, 3.

7 The Sporting News, March 7, 1940, 1.

8 The Sporting News, August 10, 1944, 3.

9 The Sporting News, April 1, 1943, 6.

10 The Sporting News, June 17, 1943, 1.

11 The Sporting News, August 10, 1944, 3.

12 The Sporting News, May 31, 1945, 8.

13 Ibid.

14 The Sporting News, October 25, 1945, 6.

15 The Sporting News, December 20, 1945, 6

16 The Sporting News, January 17, 1946, 14

17 The Sporting News, February 21, 1946, 6.

18 The Sporting News, April 11, 1946, 13.

19 The Sporting News, June 5, 1946, 7.

20 Mike Eisenbath, The Cardinals Encyclopedia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), 224.

21 The Sporting News, August 21, 1946, 2.

22 Rich Westcott, Splendor on the Diamond: Interviews with 35 Stars of Baseball’s Past (Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press, 2000), 228.

23 The Sporting News, August 14, 1946, 6.

24 The Sporting News, October 13, 1947, 1.

25 The Sporting News, January 28, 1948, 2; February 11, 1948, 1.

26 The Sporting News, September 7, 1949, 14.

27 The Sporting News, September 28, 1949, 1.

28 The “Flop” characterization appeared in The Sporting News, January 28, 1953, 8.

Full Name

Hubert Max Lanier

Born

August 18, 1915 at Denton, NC (USA)

Died

January 30, 2007 at Lecanto, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.