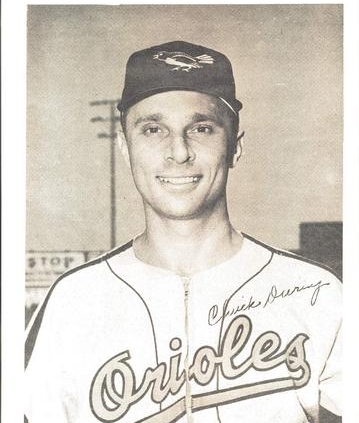

Chuck Diering

After serving his country for three years during World War II, Chuck Diering played parts of nine seasons (1947-1956) for three major league teams. Regarded as a top-notch defender by his contemporaries, the lithe center fielder became the first player to earn team Most Valuable Oriole honors when big league baseball returned to Baltimore in 1954.

After serving his country for three years during World War II, Chuck Diering played parts of nine seasons (1947-1956) for three major league teams. Regarded as a top-notch defender by his contemporaries, the lithe center fielder became the first player to earn team Most Valuable Oriole honors when big league baseball returned to Baltimore in 1954.

Charles “Chuck” Edward Allen Diering was born in St. Louis, Missouri, on February 5, 1923. He was the first of Walter and Mamie (Metzger) Diering’s two children. Brother Ray followed in 1924. Both Chuck and Ray’s maternal grandparents and paternal great-grandparents were born in Germany. Their father sold manufacturing machinery for a shoe factory after a brief U.S. Army stint during World War I. The family lived at 5663 Labadie Avenue, just over four miles northwest of Sportsman’s Park, where both the National League Cardinals and American League Browns played. “I had a few heroes, Pop Haines, Bill Hallahan, I enjoyed them,” Diering recalled.1

Chuck played softball, baseball and hockey for teams that he formed with other neighborhood kids. Initially, he was to attend Blewett High School, but he received permission to transfer to slightly closer Beaumont High. That proved fortuitous for his budding athletic career. While Diering attended the school 1938-1941, Bobby Mattick and Pete Reiser became the first of a dozen Beaumont Bluejackets alumni to reach the majors by 1961.

After playing American Legion baseball for the Aubuchon-Dennison Post 186 club in the summer of 1939, Diering joined Beaumont’s varsity squad for two years before his June 1941 graduation. “I had two scouts that were following me at that time,” he recalled. “I had the choice of signing a contract with the St. Louis Browns or the St. Louis Cardinals.” One of Diering’s teammates on both the baseball and volleyball squads was Jack Maguire, son of Cardinals’ scout Gordon Maguire. “[H]e was teaching us how to play as we were growing up in our formative years. [So] I went with the Cardinals.”2

The Cardinals gave Diering a bonus he described as “nothing” and sent him to the Hamilton Red Wings, one of the organization’s dozen Class D affiliates in 1941.3 After his father drove him more than 700 miles northeast to join the club in Ontario, Canada, however, he was told that they didn’t need outfielders. Instead, he wound up with the Daytona Beach Islanders in the Florida State League. In 59 games, he batted .213 without a home run, but he was the only player on the team who reached the majors. Still in Class D the following year, Diering improved to .305 in 126 Georgia-Florida League contests for an Albany (Georgia) Cardinals club featuring Red Schoendienst. Then, with World War II raging, “I signed a contract with Uncle Sam. I didn’t want to sign it, but I had to.”4

At Fort Sill in Lawton, Oklahoma, Diering hit .524 to lead the baseball league and homered eight times in 12 games while he trained with the U.S, Army medical corps.5 Then he was sent to Australia. “We were going to be in on the Leyte invasion, but we shipped directly to Coral Sea and then they sent us back to Australia and we set up there.” 6 After about a year, he wound up in Leyte until the end of the war. Wherever he went, he played ball. “I had the opportunity to play all kinds of sports, mostly baseball, for patients and other soldiers. I played for the 44th General Hospital in the States and Australia. On Leyte I played for Base “K”. We played Kirby Higbe‘s team in Manila.”7 When the war ended in 1945, Diering was selected to participate in what he described as “the World Series of baseball of the South Pacific” before heading home. “They flew us up there to Honolulu in Hawaii. We went up there and played Joe Garagiola and those guys.”8 Diering’s team won the championship.

Back on the mainland in 1946, the 23-year-old faced stiff competition as he attempted to restart his professional career with the Triple-A Rochester Red Wings. “With all the boys coming back from war, we had 80 guys that were trying to make this team.” 9 They were paid on a scale based on how many rounds of roster cuts they survived. Diering homered in three of the first four games and seized a spot in the starting lineup.10 By season’s end, he led the club in walks (80), steals (19) and triples (13). On defense, the 5-foot-10, 165-pounder ran down more fly balls than any center fielder in the International League.

In St. Louis that fall, the Cardinals won their fourth pennant and third World Series in five years. The Redbirds already had a graceful center fielder in Terry Moore, who had gone to four straight All-Star Games before his three-year Navy stint. When the veteran returned to the field in 1946, however, knee problems caused him to miss more than 50 games, and he was turning 35. Consequently, the Cardinals promoted Diering to the majors as a reinforcement in 1947. On Opening Day at Crosley Field, he debuted as a pinch hitter in the eighth inning and struck out against the Reds’ Ewell Blackwell.

Diering’s first hit was a double against the Cubs’ Johnny Schmitz at Sportsman’s Park on April 18. Five days later, he hit his first homer, off Pirates’ southpaw Ken Heintzelman. He stuck with the team all season and appeared in 105 games, though he received only 74 official at bats and hit just .216. Between May 2 and September 25, he started exactly once (in the second game of a doubleheader on July 6). Mostly, he pinch-ran, or finished games as a defensive replacement in center or right field. Highlights of his rookie year included throwing a runner out at home plate in the 10th inning of a 12-inning St. Louis victory at Ebbets Field on August 20, and a three-hit game at Wrigley Field on the season’s final weekend.

Heading into 1948, Cardinals manager Eddie Dyer said, “I want to get a good look at Diering, for in the closing weeks of last summer, when he got to play a lot, he showed me some great baseball.”11 After a single pinch-running appearance in April, however, the outfielder was returned to Rochester, joining his brother as a St. Louis farmhand. Ray Diering was in his second and final season as a Class D catcher. Chuck got off to a hot start, ranking among the circuit’s leaders with a .331 batting average in mid-June.12 He slumped to .266 by season’s end, however, partially because he fessed up to being credited with five hits too many.13 Though he only hit five homers, one was a grand slam while his parents were visiting. He finished the year as the club’s leader in runs scored (91) and walks (71) and ranked among the league’s top five in both doubles and triples. In center field, he gloved 442 putouts to break Frank Gilhooley’s 27-year-old International League record.14 “I really enjoyed going after fly balls,” he recalled in 2008. “I pride myself on the defensive numbers I put up in my career.”15 The Sporting News reported that kids at Rochester’s Irondequoit playgrounds voted Diering the most popular Red Wings player.16

Diering went 0-for-7 in six games with the Cardinals in September, but club vice president William Walsingham, Jr. remarked, “I’d say he’s one of the greatest prospects we have in the minors — another Terry Moore.”17 In 1949, Moore retired and joined St. Louis’s coaching staff. Diering made more than half of the starts in center and appeared in 131 games overall. When the Cardinals faced a left-handed pitcher, he was usually flanked by two Hall of Famers: Enos Slaughter in left and Stan Musial in right. “How that guy can scamper and kill off hits!” marveled the Pirates’ Hugh Casey.18 “Diering is a great ballhawk,” agreed Boston Braves skipper Billy Southworth, who opined that only Hal Jeffcoat possessed a better outfield arm in the National League.19

At the plate, Diering hit safely in a career-high 14 straight games and established personal bests in a number of batting categories, including his .263 batting average.20 “I’ve had a lot of help,” he insisted. “Dyer persuaded me to choke my grip at bat. Tony Kaufmann made me lay off high pitches. Buzzy Wares encouraged me to try a preliminary swing or two to loosen my tense shoulder muscles, and Terry Moore goes over the pitchers with me every day, showing how each is different and how they’ll try to pitch to me.”21 The Cardinals went 96-58 but lost the pennant to the Dodgers by a single game on the last day of the season.

In addition to hunting, Diering spent his early-career winters working in a warehouse. For the second straight off-season, however, he earned extra cash from barnstorming tours. In 1949, he joined a team organized by 56-year-old Hall of Famer George Sisler that traveled to Illinois, Tennessee and Kentucky.22 He’d spent the fall of ’48 with the Schoendienst Stars, an undefeated club featuring St. Louis star Red Schoendienst and three of his brothers as infielders.23 On October 29, 1949, at Saint Andrews Lutheran Church in St. Louis, Diering married Elizabeth Orrock. The daughter of a Scottish father and Polish mother, she had played basketball at the city’s Wellston High.24 Their union lasted more than 57 years until her death in 2006 and produced three children: sons Chuck, Jr. and Bob, and daughter Donna. Both his sons would become minor league catchers, peaking in Class A leagues.

Prior to the 1950 season, Dyer said of Diering, “He’s a wonderful kid, a great competitor. Too great in fact. That’s his trouble. He burns himself out.”25 The fleet center fielder began the year platooning with Harry Walker, the former NL batting champ whom the Cardinals had reacquired. On June 6, however, Diering fractured his left elbow crashing into the outfield fence and knocked himself out of action for a month.26 When he finished the season batting .250. Dodgers skipper Burt Shotton said, “Diering is no better than a .250 hitter, but the things he does on defense make him as valuable as a .400 man.”27 Unfortunately for Diering, the new Cardinals’ manager for 1951 did not share that opinion. In June skipper Marty Marion called him “a wonderful outfielder, there aren’t any better I can think of. But he just can’t hit, and we’re too weak at the bat to have him in the lineup.”28 Diering started only 17 games all season, mostly in September after St. Louis fell hopelessly out of the pennant chase. On December 11, the Cardinals traded him to the New York Giants with pitcher Max Lanier for Eddie Stanky, who became St. Louis’s player-manager.

The right-handed-hitting Diering looked forward to playing his home games at the Polo Grounds. “When I came to the Cards, I had to switch around and suit my batting to Sportsman’s Park. I didn’t have enough power to reach the fences there, so I made an effort to spray the ball into left and right-center,” he explained. “Now I’m going to switch around and I’m sure if I can get my eye on that short left field wall that I can reach [it].”29 Although the Giants already had Willie Mays, they expected to lose the 1951 Rookie of the Year to military duty. When that happened, they planned on Diering patrolling their vast center field. “Diering will get a full shot at Willie Mays’s job,” New York manager Leo Durocher insisted. “He’s my center fielder until developments prove otherwise.”30

The right-handed-hitting Diering looked forward to playing his home games at the Polo Grounds. “When I came to the Cards, I had to switch around and suit my batting to Sportsman’s Park. I didn’t have enough power to reach the fences there, so I made an effort to spray the ball into left and right-center,” he explained. “Now I’m going to switch around and I’m sure if I can get my eye on that short left field wall that I can reach [it].”29 Although the Giants already had Willie Mays, they expected to lose the 1951 Rookie of the Year to military duty. When that happened, they planned on Diering patrolling their vast center field. “Diering will get a full shot at Willie Mays’s job,” New York manager Leo Durocher insisted. “He’s my center fielder until developments prove otherwise.”30

As it developed, Diering slumped through an 0-for-38 drought during spring training.31 When the season started, he was in the lineup only four times and notched four hits. In mid-July, seven weeks after Mays entered the Army until the end of 1953, Diering was demoted to the Minneapolis Millers in the Triple-A American Association. “That was a sad experience for me,” he recalled. “After being with the Giants for a while, I just didn’t care for it… I don’t think [Durocher] spoke 10 words to me the time I was there. I was really glad to go.”32

In 55 games with the Millers, he batted .260. When he returned to Minneapolis in 1953, however, he enjoyed his best professional season — batting .322, scoring 116 runs and collecting 61 extra-base hits at age 30. “I think the man to whom I owe the most is Chick Genovese, who managed the Minneapolis club,” he said. “He kept after me to bear down on every pitch, said I could go back to the majors and gave me new life.”33 In the Cuban League that winter, Diering hit .312 for the Cienfuegos Elephants and stroked 20 doubles to lead the circuit.34

Meanwhile, Diering’s hometown Browns were moving to Baltimore. The Giants had traded him to San Francisco in the Pacific Coast League in October, but he would never suit up for the Seals. On November 30, the new American League Orioles spent $15,000 to acquire him in the Rule 5 draft.35 “We’ve got a big center field in Baltimore and we know he can go a long ways to get ‘em,” explained manager Jimmy Dykes.36 At that time, the power alleys at Baltimore’s Memorial Stadium measured a whopping 447 feet.37 Center field, 450 feet from home plate, was bordered by a tall hedge until a flimsy wire chain link fence was erected later.38 “You could get lost out there!” recalled Gil Coan.39

Coan started most of the early games in center after a strong spring but failed to lift his batting average over .200 to stay until mid-June. When Cal Abrams arrived in a May trade, he was in the lineup 12 straight times until Dykes decided he was better suited for right field. Finally, after Diering raised his own average to .350 on June 19 with six multi-hit games in 11 days, he started every game in center field for the rest of the year. In the batting order, he hit everywhere except leadoff and cleanup, usually second or third. Though a .229 average after the All-Star break dragged Diering’s overall mark down to .258, he continued to play outstanding defense. Opposing fans in both Boston and New York were moved to applaud him on a July road trip. “That fella sure can go get ‘em,” raved Yankees manager Casey Stengel.40 Sportswriter William Gildea described Diering’s fielding style: “He wore a glove barely bigger than his hand, just like the real old-timers. When he’d crouch before a pitch, he’d twist his left wrist and put it on his knee so the glove would be open and backhanded. That way, the pocket would be perfect and ready to receive the ball he would go get. Baltimore kids would try it that way, but it hurt their wrists.”41

The Orioles lost 100 games, but Diering helped them enjoy their only winning month in September. In a 1-0 victory over the Yankees on September 9, he made two tough catches to temporarily preserve Joe Coleman’s no-hit bid. Enos Slaughter broke up the no-hitter leading off the eighth inning. When Coleman beat the Red Sox, 3-1, in his next start on September 14, Diering’s throw cut down a runner at home plate to end an eighth-inning threat. On the final weekend of the season, he helped deny the Tigers a fourth-place finish (and share of the playoff money) with a running grab with two aboard to end a one-run game.42

Near the end of the season, the Orioles planned to award a Cadillac to the team’s most popular player. “I said, ‘Man, I’m a popular player in this town here, and I’m gonna get me a Cadillac’,” Diering recalled. Instead, rookie pitcher Bob Turley received the car, while Diering took home a trophy as the team’s inaugural Most Valuable Oriole. In an interview 58 years later he remarked, “Bob Turley don’t have the Cadillac, but I’ve got my trophy right up here in my trophy case.”43

A 17-player trade that sent Turley to the Yankees in November was the first clue that Baltimore’s incoming GM/manager Paul Richards intended to shake up the roster for 1955. Diering arrived at spring training aware that the new boss planned to return him to a platoon or reserve role. “I started out as a sub last year and became a regular,” he noted. “I figure that situation will work itself out in due time.”44 Though Diering was not in the starting lineup until the ninth game, he notched his only career four-hit games during the next two days and went on to lead the team in center field starts for the second straight year.

On May 27, 1955, he made a catch that “old Oriole fans are still talking about” according to the team’s 20th anniversary yearbook.45 The visiting Yankees were leading in the top of the ninth when Mickey Mantle, who had tripled and doubled in his prior two at bats, stepped to the plate. Batting left-handed against Erv Palica, Mantle crushed a towering drive that initially appeared destined to clip the corner of the scoreboard, 450 feet away in right-center. “As soon as the ball was hit, Diering turned his back and ran as hard as he could,” columnist Bob Maisel described. “Still heading toward the fence at full speed, Chuck grabbed the ball at least 440 feet from the plate.”46 A New York writer called it a “Willie Mays catch.”47 The Sporting News said it was “the longest out since the stadium was constructed”.48 As Diering gloved the ball, right fielder Hoot Evers tripped over him and both players fell. The center fielder held onto the ball, however, delighting the Friday-night crowd. Diering robbed Mantle of another extra-base hit in almost the same spot the next day.49 Three weeks later, Diering played the infield for the first time as a professional, replacing Willy Miranda for an inning after the light-hitting shortstop had left for a pinch hitter. Over the next six weeks, Diering played errorless ball in a dozen appearances at shortstop. He also played third base for the first time in June. By season’s end, he’d started 25 games at the hot corner, third most among the 10 players Richards tried there in 1955.

By 1956, Diering was the last player remaining from Baltimore’s 1954 club. Tito Francona, a 22-year-old rookie who had led the Colombian winter league in home runs, was the Opening Day center fielder.50 Jim Pyburn, 23, received his chance next after Francona struggled, but Diering made every start for three weeks in May. Despite an inside-the-park homer — his final round-tripper in the majors — the 33-year-old could not hold the job. He was batting just .186 when the Orioles sent him to the Dodgers with $15,000 for Dick Williams on June 24.51 He finished the season with the Montreal Royals in the Triple-A International League, hitting .241 in 57 games.

Prior to the 1957 season, Diering called St. Louis GM Frank Lane seeking a homecoming. Though Lane cautioned that his team really wanted power hitters, he acquired his contract and sent him to the Omaha Cardinals in the Triple-A American Association. Diering batted just .220 with two homers in 78 games, however, and was sold to the Orioles’ PCL Vancouver Mounties in mid-July. That winter, the Orioles sold his contract to the Louisville Colonels, an American Association club they had signed an agreement with. In April 1958, however, the Colonels suspended Diering for failing to report.52 “When you have a home that you’ve got to pay for in St. Louis, and you’ve got rent a home in Omaha, or Louisville or wherever you’re going to play…I would really go in a hole by the time I paid the taxes, and I retired.”53

Over nine seasons, Diering produced a .249 batting average and 14 home runs in 752 major league games. “I wish I could have finished my career with a higher batting average,” he confessed in 2008. “But with my limited at bats with the Giants and last year with the Orioles, [it really] hurt my average.”54 In the minors, he played in 882 contests and hit .275. He liked selling cars and had an opportunity to acquire an Edsel franchise, so he began his post-baseball career looking for a suitable location in St. Louis. Instead, when he learned about an existing Ford dealership for sale about 25 miles north in Alton, Illinois, he bought it with his partners and ran it until 1980. “Then I went to work for a customized van company for four years,” he said. “Then in 1986, I retired.”55 He spent the rest of his life living in the Spanish Lake home he’d built in 1957, playing golf a few times per week.

In October 1991, Diering returned to Memorial Stadium for the ballpark’s closing weekend. He was one of only six players from the original 1954 team on hand for the emotional ceremonies. “I enjoyed playing in the outfield there,” he recalled. “You had to judge playing balls hit off the walls coming off at different angles. You had a chance to throw out guys at second base.”56 During Baltimore’s final season at the ballpark, his ’54 club record of 17 outfield assists was broken by Joe Orsulak. As of 2020, Diering’s ’54 total of six outfield double plays has never been topped by an Orioles’ outfielder.57

On Thanksgiving Day 2012, Bob Diering discovered that his 89-year-old father had fallen at home. Suffering from cerebral hemorrhaging, Chuck Diering died a few hours later, on November 23, 2012. He is buried next to his wife at the Jefferson National Barracks Cemetery in St. Louis.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Gregory H. Wolf and Norman Macht and fact-checked by Alan Cohen.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted www.ancestry.com, www.baseball-reference.com and www.retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 Brent Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: Interviews with Baseball Players of the 1940s, McFarland and Company, Inc. (Jefferson, North Carolina, 2001): 271.

2 Kristin Diering, “The Golden Years: The Story About One Man Who Lived His Dream,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IW5KwBkGCSA&t=38s (last accessed November 21, 2020).

3 Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: 267.

4 Valerie E. Wilson, “Interview with Chuck Diering,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zuU0gk1U008 (last accessed November 21, 2020).

5 Gary Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime: Chuck Diering,” https://www.baseballinwartime.com/player_biographies/diering_chuck.htm (last accessed November 21, 2020).

6 Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: 267.

7 Bedingfield, “Baseball in Wartime: Chuck Diering.”

8 Diering, “The Golden Years: The Story About One Man Who Lived His Dream.”

9 Wilson, “Interview with Chuck Diering.”

10 Chuck Diering, 1950 Bowman Baseball Card.

11 Ray Gillespie, “Making Right Choices on Cards Mound Staff Dyers Main Concern,” The Sporting News, February 4, 1948: 14.

12 “Int Averages,” The Sporting News, June 23, 1948: 19.

13 “Rochester,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1948: 22.

14 “Diering Makes Fielding Record for International,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), December 8, 1948: 18.

15 Chuck Diering, Letter to Malcolm Allen, September 25, 2008.

16 “Rochester,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1948: 22.

17 Ray Gillespie, “Future Redbird Stars Being Prepped for Calls,” The Sporting News, July 21, 1948: 11.

18 “What Put Cards in Race? Pollet’s Comeback — Casey,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1949: 6.

19 George Beahon, “Diering ‘Great’ Says Billy,” Democrat and Chronicle (Rochester, New York), June 28, 1949: 21.

20 During Diering’s 14-game hitting streak, he also appeared in five other games in which he didn’t make a plate appearance.

21 Bob Broeg, “Hats Off…!” The Sporting News, June 29, 1949: 19

22 “Major Barnstormers Swing into Action on Many Trails,” The Sporting News, October 19, 1949: 26.

23 “Four Schoendienst Brothers on Infield,” The Sporting News, October 27, 1948: 21.

24 “Diering, Lanier of Cards Married on Same Day,” The Sporting News, November 9, 1949: 19.

25 Robert L. Burnes, “Can Lefties Hit Lefties?” The Sporting News, November 16, 1949: 10.

26 Bob Broeg, “Cards’ Chins Up,” The Sporting News, June 14, 1950: 7.

27 “Cards Diering Compared to Moore as Defense Star,” The Sporting News, July 26, 1950: 5.

28 Clif Keane, “Cards Would Trade Diering, Says Marion,” Daily Boston Globe, June 10,1951: C45.

29 Jim McCully, “Diering Shifts Stance, Now Aims at PG Wall,” Daily News (New York), February 25, 1952: 196.

30 “Giants,” The Sporting News, February 13,1952: 2.

31 Ed Sinclair, “Diering’s Single, His First Hit in 39 Tries, Proves Decisive,” New York Herald Tribune, April 12, 1952: 15.

32 Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: 269.

33 Hugh Trader, Jr., “Chuck Third Castoff Gem with Orioles,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1954: 8.

34 Pedro Galiana, “Rocky’s .352 Wins Batting Title in Cuba,” The Sporting News, February 24, 1954: 25.

35 Hugh Trader, Jr. “Ehlers Launches Orioles Shakeup by Drafting Pair,” The Sporting News, December 9, 1953: 4.

36 Ben Olan, “Chuck Diering Key Figure in Baltimore,” Ithaca Journal, February 6, 1954: 10.

37 1955 Baltimore Orioles Media Guide: 14.

38 “Memorial Stadium,” https://ballparks.com/baseball/american/memori.htm (last accessed November 23, 2020).

39 Gil Coan, Letter to Malcolm Allen, November 2005.

40 Hugh Trader, Jr., “Chuck Third Castoff Gem with Orioles,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1954: 8.

41 William Gildea, “Plight of ’87, Images of ’54,” Washington Post, June 27, 1987: C01.

42 Ned Burks, “Big Outfield Helps Birds,” Baltimore Sun, September 22, 1954: 15.

43 Diering, “The Golden Years: The Story About One Man Who Lived His Dream.”

44 Bob Maisel, “Outfielder Accepts 3d Bird Offer,” Baltimore Sun, February 23, 1955: 15.

45 “Chuck Diering,” Baltimore Orioles 20th Anniversary Yearbook 1974: 43.

46 Bob Maisel, “Robinson’s 3-Run Homer Helps Yanks Top Orioles, 6-2,” Baltimore Sun, May 28,1955:11.

47 Joe Trimble, “Robinson HR Powers Ford, 6-2,” Daily News (New York), May 28, 1955: 217.

48 Jesse Linthicum, “Baltimoreans Sore as Boil Over Bruises by Bombers,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1955: 10.

49 Louis Effrat, “Lopat of Yankees Tops Orioles, 3-2,” New York Times, May 29, 1955: 113.

50 “Richards Enters Francona in Orioles’ Centerfield Race,” The Sporting News, February 29, 1956: 20.

51 Jim Ellis, “Hats Off…!” The Sporting News, April 24, 1957: 20.

52 “American Association,” The Sporting News, April 30, 1958: 39.

53 Wilson, “Interview with Chuck Diering.”

54 Chuck Diering, Letter to Malcolm Allen, September 25, 2008.

55 Kelley, The Pastime in Turbulence: 271.

56 Chuck Diering, Letter to Malcolm Allen, November 2005.

57 Both Brady Anderson (1992) and Adam Jones (2010) have also participated in six double plays in a season for Baltimore.

Full Name

Charles Edward Allen Diering

Born

February 5, 1923 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

Died

November 23, 2012 at St. Louis, MO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.